From Median to Achaemenian Palace Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Bahman Jalali1

11 Interview with Bahman Jalali1 By Catherine David2 Catherine David: Among all the Muslim countries, it seems that it was in Iran where photography was first developed immediately after its invention – and was most inventive. Bahman Jalali: Yes, it arrived in Iran just eight years after its invention. Invention is one thing, what about collecting? When did collecting photographs beyond family albums begin in Iran? When did gathering, studying and curating for archives and museum exhibitions begin? When did these images gain value? And when do the first photography collections date back to? The problem in Iran is that every time a new regime is established after any political change or revolution – and it has been this way since the emperor Cyrus – it has always tried to destroy any evidence of previous rulers. The paintings in Esfahan at Chehel Sotoon3 (Forty Pillars) have five or six layers on top of each other, each person painting their own version on top of the last. In Iran, there is outrage at the previous system. Photography grew during the Qajar era until Ahmad Shah Qajar,4 and then Reza Shah5 of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah held a grudge against the Qajars and so during the Pahlavi reign anything from the Qajar era was forbidden. It is said that Reza Shah trampled over fifteen thousand glass [photographic] plates in one day at the Golestan Palace,6 shattering them all. Before the 1979 revolution, there was only one book in print by Badri Atabai, with a few photographs from the Qajar era. Every other photography book has been printed since the revolution, including the late Dr Zoka’s7 book, the Afshar book, and Semsar’s book, all printed after the revolution8. -

Service Quality Approach in Development of Children's Visit Model

SERVICE QUALITY APPROACH IN DEVELOPMENT OF CHILDREN'S VISIT MODEL. CASE STUDY GOLESTAN PALACE MUSEUM, TEHRAN, IRAN Seyedeh Yasamin Hosseini Per citar o enllaçar aquest document: Para citar o enlazar este documento: Use this url to cite or link to this publication: http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/667502 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. -

Hilary Gopnik Facebook: Naxarchaeology

[email protected] Hilary Gopnik http://oglanqala.net/ facebook: NaxArchaeology Current Position: Co-Director, Naxçivan Archaeological Project Senior Lecturer/Principal Scientist, Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies, Emory University EDUCATION Ph.D., University of Toronto, 2000 Major: West Asian Archaeology Minor: Archaeology of the Levant Thesis: The Ceramics of Godin II (Supervised by T. Cuyler Young Jr.) Awards: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Doctoral Fellowship; Ontario Graduate Fellowship; Graduate Studies Travel Grants; Junior Scholar Stipend, Achaemenid History Workshop VIII, Ann Arbor, Michigan M.A., University of Toronto, 1985 Major: Near Eastern Archaeology Awards: Ontario Graduate Fellowship; Graduate Studies Travel Grants B.A., First Class Honours, McGill University, 1982 Major: Anthropology Minor: Classics Honours Thesis: Systems Theory in Archaeology (Supervised by Prof. Bruce Trigger) Awards: James McGill Award; University Scholar; Faculty Scholar; Award for highest achievement in Prof. Bruce Trigger's "History of Archaeological Theory" Foreign languages: Modern: French (fluent), Italian, German, Azerbaijani (reading, spoken) Ancient: Akkadian, Greek PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT MIT Summer Institute in Materials Science and Material Culture, 2004. Intensive post-doctoral seminar in the scientific study of material culture. ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELDWORK 2016–2017, Ceramicist, Pasargadae Research Project, Pasargadae, Iran, directed by Sébastien Gondet, CNRS 2014–2015 (ongoing), Co-Director, -

MISYZA 10D7N Wonders of Iran P44-46.Ai

PREMIUM 10D7N WONDERS OF IRAN TOUR CODE: MISYZA Explore the history of Iran through its and colourful gardens. Wander the streets and explore the ancient cities, that encapsulate much of Iran’s rich history and culture. NASIR ALMOLK MOSQUE, SHIRAZ 44 Exotic | EU Holidays HIGHLIGHTS IRAN SHIRAZ • Nasir al-Mulk Mosque • Zandieh Complex • Qavam House • Eram Gardens Tehran 1 • Karim Khan Fortress IRAN • Ancient Ruins of Persepolis (UNESCO) Kashan • Naqsh-e Rustam & Rajab 3 Yazd • Hafezieh and the Saadieh Isfahan 1 • Pasargadae Tomb of Cyrus The Great (UNESCO) Persepolis Pasargadae YAZD Flight path • Abarkooh Adobe Ice House 2 • Jameh Mosque Traverse by coach Shiraz • Amir Chakhmaq Complex Featured destinations • Water Museum • Old City with Fire Temple Overnight stays 1 2 3 • Towers of Silence ISFAHAN • Imam Square (UNESCO) • Ali Qapu Palace • • Chehel Sotoun Palace (UNESCO) DAY 1 • Bridge of 33 Arches Eram), one of the most beautiful and • Vank Cathedral HOME SHIRAZ Meals on Board monumental gardens of Iran. • Jameh Mosque of Isfahan Assemble at the airport and depart for Shiraz, • Isfahan Bazaar one of the oldest cities of ancient Persia. DAY 4 KASHAN SHIRAZ PASARGADAE YAZD • Fin garden (UNESCO) DAY 2 Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner • Tabātabāei House SHIRAZ Today, make your way to Pasargadae,the • Borujerdis House Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner ancient capital and burial site of Cyrus the • Sultan Amir Ahmad Bathhouse Upon your arrival, begin your tour with the Great, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. TEHRAN highlights of Shiraz, the former capital of Visit the Tomb of Cyrus the Great and • Azadi Tower Iran during the Zand Dynasty. Be inspired remains of Achaemenian palaces and • Golestan Palace by the glorious Karim Khan Fortress and edifices. -

Iran in Depth

IRAN IN DEPTH In conjunction with the Near East Archaeological Foundation, Sydney University APRIL 25 – MAY 17, 2017 TOUR LEADER: BEN CHURCHER Iran in depth Overview The Persian Empire, based within modern Iran’s borders, was a significant Tour dates: April 25 – May 17, 2017 force in the ancient world, when it competed and interacted with both Greece and Rome and was the last step on the Silk Road before it Tour leader: Ben Churcher reached Europe and one of the first steps of Islam outside Arabia. In its heyday, Iran boasted lavish architecture that inspired Tamerlane’s Tour Price: $11,889 per person, twin share Samarqand and the Taj Mahal, and its poets inspired generations of Iranians and foreigners, while its famed gardens were a kind of earthly Single Supplement: $1,785 for sole use of paradise. In recent times Iran has slowly re-established itself as a leading double room nation of the Middle East. Booking deposit: $500 per person Over 23 days we travel through the spring-time mountain and desert landscapes of Iran and visit some of the most remarkable monuments in Recommended airline: Emirates the ancient and Islamic worlds. We explore Achaemenid palaces and royal tombs, mysterious Sassanian fire temples, enchanting mud-brick cities on Maximum places: 20 the desert fringes, and fabled Persian cities with their enchanting gardens, caravanserais, bazaars, and stunning cobalt-blue mosques. Perhaps more Itinerary: Tehran (3 nights), Astara (1 night), importantly, however, we encounter the unsurpassed friendliness and Tabriz (3 nights), Zanjan (2 nights), Shiraz (5 hospitality of the Iranian people which leave most travellers longing to nights), Yazd (3 nights), Isfahan (4 Nights), return. -

9730 Ira.Ant. 04 Magee

Iranica Antiqua, vol. XXXII, 1997 THE IRANIAN IRON AGE AND THE CHRONOLOGY OF SETTLEMENT IN SOUTHEASTERN ARABIA BY Peter MAGEE University of Sydney Introduction1 Within West Asian archaeology, research into the Iron Age of South- eastern Arabia (or Oman Peninsula) has recently emerged as an area of interest. From tentative beginnings in the 1960s, a wealth of archaeological material now exists that allows an understanding of the processes of domestic cultural change in this region. From the beginnings of research the influence of Iran on the material culture of this region was recognised, as was the chronological importance of these contacts. The purpose of this paper is to focus on cross-Gulf contacts in the Iron Age and their impor- tance in dating the recently re-dated Rumeilah assemblage (Boucharlat and Lombard 1991). It must be emphasised that research into this region is still at a formative stage; if this paper generates further discussions and even contradictions to the ideas presented here, it will have achieved its purpose. Rumeilah and the Iron Age of Southeastern Arabia Since 1985, archaeologists working in Southeastern Arabia have bene- fited greatly from the evidence uncovered by the French Archaeological 1 The term “Southeastern Arabia” is used here to denote the area sometimes referred to as the Oman Peninsula. In essence, this area is the modern countries of the Sultanate of Oman and the United Arab Emirates. This paper grew out of the author’s Phd dissertation (Magee 1995). I would like to take the opportunity to thank Professor D.T. Potts (Sydney) who, in addition to introducing me to the archaeology of Southeastern Arabia and provid- ing me with complete access to the material from Tell Abraq, kindly read drafts of this article. -

Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC) Dome Design

International Journal of Civil and Structural Engineering Research ISSN 2348-7607 (Online) Vol. 3, Issue 2, pp: (39-45), Month: October 2015 - March 2016, Available at: www.researchpublish.com Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC) Dome Design SHAIK TAHASEEN II M.TECH, DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING, VISVODAYA ENGINEERING COLLEGE, KAVALI ABSTRACT: A dome may be defined as a thin shell generated by the revolution of a regular curve about one of its axes. The shape of the dome depends up on the type of the curve and direction of the axis of revolution. The roof is curved and used to cover large storey buildings. The shell roof is useful when inside of the building is open and does not contain walls or pillars. Domes are used in variety of structures such as roof of circular areas, circular tanks, exhibition halls, auditoriums etc. Domes may be constructed of masonry, steel, timber and reinforced cement concrete. In this paper we design RCC dome roof structure by using manual methods which gives detail design of RCC domes. The procedure of designing RCC domes was clearly explained and from the Analysis and design we get the Meridional Reinforcement, hoop Reinforcement of a dome and ring beam Reinforcement Keywords: Dome, wind load, live load and dead load, Analysis, diameter of dome. 1. INTRODUCTION In the past and recent years, there have been an increasing number of structures using RCC domes as one of the most efficient shapes in the world. It covers the maximum volume with the minimum larger volumes with no interrupting columns in the middle with an efficient shapes would be more efficient and economic. -

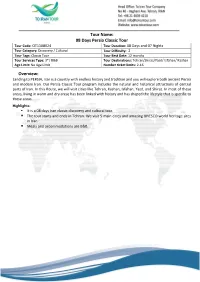

Tour Name: 08 Days Persia Classic Tour Overview

Tour Name: 08 Days Persia Classic Tour Tour Code: OT1108024 Tour Duration: 08 Days and 07 Nights Tour Category: Discovery / Cultural Tour Difficulty: 2 Tour Tags: Classic Tour Tour Best Date: 12 months Tour Services Type: 3*/ B&B Tour Destinations: Tehran/Shiraz/Yazd/ Isfahan/ Kashan Age Limit: No Age Limit Number ticket limits: 2-16 Overview: Landing to PERSIA, Iran is a country with endless history and tradition and you will explore both ancient Persia and modern Iran. Our Persia Classic Tour program includes the natural and historical attractions of central parts of Iran. In this Route, we will visit cities like Tehran, Kashan, Isfahan, Yazd, and Shiraz. In most of these areas, living in warm and dry areas has been linked with history and has shaped the lifestyle that is specific to these areas. Highlights: ▪ It is a 08 days Iran classic discovery and cultural tour. ▪ The tour starts and ends in Tehran. We visit 5 main cities and amazing UNESCO world heritage sites in Iran. ▪ Meals and accommodations are B&B. Tour Itinerary: Landing to PERSIA Welcome to Iran. To be met by your tour guide at the airport (IKA airport), you will be transferred to your hotel. We will visit the lavish Golestan Palace*, this fabulous walled complex is centered on a landscaped garden with tranquil pools. Time permitting; we can walk around Grand old Bazaar of Tehran, few steps far from Golestan Palace. Continue along the Bazaar route. Then at night, we take a flight to Shiraz. O/N Shiraz Note: The priority in sightseeing may be changed due to the time of your arrival, preference of your guide and also official and unofficial holidays of some museums. -

Reviewing the Khorshid Gate in Naqshe Jahan Square Based on the Historical- Descriptive and Image Documents Nima Valibeig*1

Bagh- e Nazar, 16 (73):45-58 /Jul. 2019 DOI: 10.22034/bagh.2019.135488.3625 Persian translation of this paper entitled: بازخوانی سردر خورشید در میدان نقش جهان براساس اسناد توصیفی-تاریخی و تصویری is also published in this issue of journal. Reviewing the Khorshid Gate in Naqshe Jahan Square Based on the Historical- Descriptive and Image Documents Nima Valibeig*1, Negar Kourangi2 1. Restoration and conservation faculty, Isfahan Art University, Iran. 2. Restoration and conservation faculty, Isfahan Art University, Iran. Received 2018/06/25 revised 2018/12/17 accepted 2018/12/23 available online 2019/06/22 Abstract Statement of problem: Naghsh-e Jahan square has been formed as a prominent urban space in Isfahan with the interaction of economic-residential, religious, and governmental sectors in the Safavid period. This square has entrances to connect with each other. One of this square’s routes was toward governmental part is the gate known as Khorshid. The study of this gate helps to identify the uses around the square, spatial relationships, and hierarchy of access during the history. Some researchers study the transformations in square and evaluate Naghsh-e Jahan square. This research reviews the Khorshid gate for the first time based on the historical-descriptive and visual documents of Safavid era until first Pahlavi period. Methodology: this research has used library and field data. By evaluating the descriptive and visual documents of different historical periods and present condition, the evolution process of gate was determined from Safavid era until the collapse of Pahlavi. Purpose: This research aims to explain the evolution process and the use of the Khorshid gate from Safavid period until today by evaluating available historical-descriptive and image document. -

He Found the Oldest-Known Beer on the Planet... the Biomolecular Archaeology of Ancient Alcoholic Beverages

BREWING HISTORY l Penn Museum main gate and Warden’s garden He found the oldest-known beer on the planet... The biomolecular archaeology of ancient alcoholic beverages By Ian Hornsey In May 2016 the World Beer Cup, splendidly organised by the Brewers’ Association, was held in Philadelphia, the city where the ‘American Dream’ began. Having been invited to judge at the event, my thoughts turned to the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) and its excellent Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (known as The Penn Museum) – with its world-renowned Biomolecular Archaeology Project. McGovern in the laboratory f time permitted, I might be able to After three hectic days of judging, I Health. He is also Adjunct Professor Itake the short train journey from our managed to find a mutually convenient of Anthropology at UPenn, where he downtown base, the Pennsylvania Con- slot for my visit to UPenn and caught teaches molecular archaeology. vention Centre (PCC) and meet up with the highly efficient SEPTA (Southeast- Much of McGovern’s earlier work at Penn Museum’s Dr Patrick McGovern ern Pennsylvania Transportation Au- Penn Museum was carried out under the whose interests in the history of alco- thority) train from Jefferson, a station auspices of the Museum Applied Science holic beverages very much coincide almost inside PCC, to the University Centre for Archaeology (MASCA), which with mine. City stop, roughly midway between first saw the light of day in 1961 and In fact, the chap I was going to meet downtown and the airport. At the mu- from which studies on ancient organic has identified the world’s oldest known seum, I was met by McGovern, known materials were carried out. -

Iran in Depth

IRAN IN DEPTH In conjunction with the Near East Archaeological Foundation, Sydney University APRIL 25 – MAY 17, 2017 TOUR LEADER: BEN CHURCHER Iran in depth Overview The Persian Empire, based within modern Iran’s borders, was a significant Tour dates: April 25 – May 17, 2017 force in the ancient world, when it competed and interacted with both Greece and Rome and was the last step on the Silk Road before it Tour leader: Ben Churcher reached Europe and one of the first steps of Islam outside Arabia. In its heyday, Iran boasted lavish architecture that inspired Tamerlane’s Tour Price: $11,889 per person, twin share Samarqand and the Taj Mahal, and its poets inspired generations of Iranians and foreigners, while its famed gardens were a kind of earthly Single Supplement: $1,785 for sole use of paradise. In recent times Iran has slowly re-established itself as a leading double room nation of the Middle East. Booking deposit: $500 per person Over 23 days we travel through the spring-time mountain and desert landscapes of Iran and visit some of the most remarkable monuments in Recommended airline: Emirates the ancient and Islamic worlds. We explore Achaemenid palaces and royal tombs, mysterious Sassanian fire temples, enchanting mud-brick cities on Maximum places: 20 the desert fringes, and fabled Persian cities with their enchanting gardens, caravanserais, bazaars, and stunning cobalt-blue mosques. Perhaps more Itinerary: Tehran (3 nights), Astara (1 night), importantly, however, we encounter the unsurpassed friendliness and Tabriz (3 nights), Zanjan (2 nights), Shiraz (5 hospitality of the Iranian people which leave most travellers longing to nights), Yazd (3 nights), Isfahan (4 Nights), return. -

Local Architecture: Using Traditional Persian Elements to Design for Climate in Yazd, Iran

Local Architecture: Using Traditional Persian Elements to Design for Climate in Yazd, Iran by Sepideh Sohrabi Mollayousef A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Architecture in M. Architecture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2015 Sepideh Sohrabi Mollayousef 1 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to research and study vernacular architecture in Yazd. Additionally, this study will explore the social and environmen- tal bases of the traditional Yazdi house. In order to develop a cohesive understanding of contemporary issues in Iranian design, a variety of resource materials will be drawn on, including journal articles, reports, books, and field studies. The thesis will culminate in a project to design a large-scale master plan and schematic housing layouts for a residential complex at Yazd University that will house professors and their immedi- ate family members. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to express my gratitude to my supervi- sor, Prof. Johan Voordouw, who has supported me with his patience and knowledge whilst allowing me to develop my research. Also I would like to offer special thanks to my committee chair, Dr. Fed- erica Goffi, for her offered guidance, care and support. I also want to thank Dr. Inderbir Singh Riar and Marjan Ghannad for serving on my graduate committee. I would like to thank my father, Dr. Teymour Sohrabi, and dear mother, Fariba Zamani Sani, for each providing me with love, encouragement and support. Special thanks go to my amazing sister, Sara, who has provided inexhaustible love, support and encouragement.