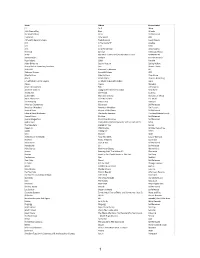

Full Music Credits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Echoes of Pacific War

ECHOES of Pacific War Edited by Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell Echoes of Pacific War Edited by Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell Papers from the 7th Tongan History Conference held in Canberra in January 1997 TARGET OCEANIA CANBERRA 1998 © Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell 1998 This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Book and cover design by Jennifer Terrell Printed by ANU Printing and Publishing Service ISBN 0-646-36000-0 Published by TARGET OCEANIA c/ o Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia Contents Maps and Figures v Fo reword ix Introduction xiii 1 Behind the battle lines: Tonga in World War II EUZABETHWOOD-EILEM 1 2 Changing values and changed psychology of Tongans during and since World War II 'I. F. HELU 26 3 Airplanes and saxaphones: post-war images in the visual and peiforming arts ADRIENNE L. KAEPPIER 38 4 Tonga and Australia since Wo rld War II GARETH GRAINGER 64 5 New behaviours and migration since Wo rld War II SIOSIUA F. POUVALU LAFITANI 76 6 The churches in Tonga since World War II JOHN GARRE'IT 87 7 Introduction and development of fa mily planning in Tonga 1958-1990 HENRY IVARATURE 99 8 Analysing the emergent mi ddle class - the 1990s KERRY JAMES 110 9 Changing interpretations of the kava ritual MEREDITH FILIHIA 127 10 How To ngan is a Tongan? Cultural authenticity revisited HELEN MORTON 149 Bibliograp hy 167 Index 173 Contributors 182 Maps Map 1: TheTonga Islands vii Map 2: Tongatapu 5 Map 3: Nuku'alofa 10 Figures Figure 1. -

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

![Short Stories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3643/short-stories-93643.webp)

Short Stories]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1999 Riparia| [Short stories] Danis Banks The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Banks, Danis, "Riparia| [Short stories]" (1999). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3447. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3447 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M I llMliw Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of MONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission /<? ^ Author's Signature. Date (7, Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. RIPARIA by Danis Banks B.A. Brown University, 1993 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts The University of Montana 1999 Approved by: Chairperson Dean, Graduate School S-l 7-<7? Date UMI Number: EP34091 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. -

2015 Year in Review

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Concert and Music Performances Ps48

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Collection CONCERT AND MUSIC PERFORMANCES PS48 This collection of posters is available to view at the State Library of Western Australia. To view items in this list, contact the State Library of Western Australia Search the State Library of Western Australia’s catalogue Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1975 April - September 1975 PS48/1975/1 Perth Concert Hall ABC 1975 Youth Concerts Various Reverse: artists 91 x 30 cm appearing and programme 1979 7 - 8 September 1979 PS48/1979/1 Perth Concert Hall NHK Symphony Orchestra The Symphony Orchestra of Presented by The 78 x 56 cm the Japan Broadcasting Japan Foundation and Corporation the Western Australia150th Anniversary Board in association with the Consulate-General of Japan, NHK and Hoso- Bunka Foundation. 1981 16 October 1981 PS48/1981/1 Octagon Theatre Best of Polish variety (in Paulos Raptis, Irena Santor, Three hours of 79 x 59 cm Polish) Karol Nicze, Tadeusz Ross. beautiful songs, music and humour 1989 31 December 1989 PS48/1989/1 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Elisa Wilson Embleton (soprano), John Kessey (tenor) Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1990 7, 20 April 1990 PS48/1990/1 Art Gallery and Fly Artists in Sound “from the Ros Bandt & Sasha EVOS New Music By Night greenhouse” Bodganowitsch series 31 December 1990 PS48/1990/2 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Emma Embleton Lyons & Lisa Brown (soprano), Anson Austin (tenor), Earl Reeve (compere) 2 November 1990 PS48/1990/3 Aquinas College Sounds of peace Nawang Khechog (Tibetan Tour of the 14th Dalai 42 x 30 cm Chapel bamboo flute & didjeridoo Lama player). -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

S a L L Y S E T L I

S A L L Y S E T L I S T Popular ❖ Dancing Queen - ABBA ❖ Long Way To The Top - AC/DC ❖ Make you feel my love - Adele ❖ rolling in the deep - adele ❖ When We Were Young - Adele ❖ One and Only - Adele ❖ Let’s Stay Together - Al Green ❖ If Trouble Was Money - Albert Collins ❖ Empire State of mind - Alicia Keys ❖ If I Ain’t Got You - Alicia Keys ❖ I’ll Fly Away - Alison Krauss ❖ Oh Atlanta - Alison Krauss ❖ One Way Out - Allman Brothers Band ❖ Wake Me Up - Aloe Blacc ❖ I Need A Dollar - Aloe Blacc ❖ Rehab - Amy Winehouse ❖ Valerie - Amy Winehouse ❖ Bella - Angus and Julia Stone ❖ Big Jet Plane - Angus and Julia Stone ❖ The Girl From Ipanema - Antonio Carlos Jobim ❖ I Bet that You Look Good On the Dancefloor - Arctic Monkeys ❖ Chain of Fools - Aretha Franklin ❖ I Say A Little Prayer - Aretha Franklin ❖ R-E-S-P-E-C-T - Aretha Franklin ❖ One Crowded Hour - Augie March ❖ Wake Me Up - Avicii ❖ Let The Good Times Roll - B B King ❖ Three O’clock Blues - B B King ❖ Fight For Your Right - Beastie Boys ❖ How Deep Is Your Love - Bee Gees ❖ Stand by me - Ben E. King ❖ The Luckiest - Ben Folds ❖ Steal My Kisses - Ben Harper ❖ Wish You Well - Bernard Fanning ❖ XO - Beyonce ❖ Ain’t No Sunshine - Bill Withers ❖ Use Me - Bill Withers ❖ Everything I Wanted - Billie Eilish ❖ Just The Way You Are - Billy Joel ❖ Achy Breaky Heart - Billy Ray Cyrus ❖ I Gotta Feeling - Black Eyed Peas ❖ No Diggity - Blackstreet ❖ All The Small Things - Blink 182 ❖ Dammit - Blink 182 ❖ Make You Feel My Love - Bob Dylan ❖ Mr Tambourine Man - Bob Dylan ❖ I Shot The Sherrif - Bob Marley -

Mitchell Brothers – Vaudeville and Western

Vaudeville and the Last Encore By Marlene Mitchell February, 1992 William Mitchell, his wife Pearl Mitchell, and John Mitchell 1 Vaudeville and the Last Encore By Marlene Mitchell February, 1992 Vaudeville was a favorite pastime for individuals seeking clean entertainment during the early part of the 20th century. The era of vaudeville was relatively short because of the creation of new technology. Vaudeville began around 1881 and began to fade in the early 1930s.1 The term vaudeville originated in France.2 It is thought that the term vaudeville was from “Old French vaudevire, short for chanson du Vaux de Vire, which meant popular satirical songs that were composed and presented during the 15th century in the valleys or vaux near the French town of Vire in the province of Normandy.”3 How did vaudeville begin? What was vaude- ville’s purpose and what caused its eventual collapse? This paper addresses the phenomenon of vaudeville — its rise, its stable but short lifetime, and its demise. Vaudeville was an outgrowth of the Industrial Revolution, which provided jobs for peo- ple and put money in their pockets.4 Because of increased incomes, individuals began to desire and seek clean, family entertainment.5 This desire was first satisfied by Tony Pastor, who is known as the “father of vaudeville.”6 In 1881 Pastor opened “Tony Pastor’s New Fourteenth Street Theatre” and began offering what he called variety entertainment.7 Later B. F. Keith, who is called the “founder of vaudeville,” opened a theater in Boston and expanded on Pastor’s original variety concept.8 Keith was the first to use the term “vaudeville” when he opened his theater in Boston in 1894.9 Keith later joined with E. -

The Use of Short-Term Group Music Therapy for Female College Students with Depression and Anxiety by Barbara Ashton a Thesis P

The Use of Short-Term Group Music Therapy for Female College Students with Depression and Anxiety by Barbara Ashton A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Approved April 2013 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Barbara Crowe, Chair Robin Rio Mary Davis ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 ABSTRACT There is a lack of music therapy services for college students who have problems with depression and/or anxiety. Even among universities and colleges that offer music therapy degrees, there are no known programs offering music therapy to the institution's students. Female college students are particularly vulnerable to depression and anxiety symptoms compared to their male counterparts. Many students who experience mental health problems do not receive treatment, because of lack of knowledge, lack of services, or refusal of treatment. Music therapy is proposed as a reliable and valid complement or even an alternative to traditional counseling and pharmacotherapy because of the appeal of music to young women and the potential for a music therapy group to help isolated students form supportive networks. The present study recruited 14 female university students to participate in a randomized controlled trial of short-term group music therapy to address symptoms of depression and anxiety. The students were randomly divided into either the treatment group or the control group. Over 4 weeks, each group completed surveys related to depression and anxiety. Results indicate that the treatment group's depression and anxiety scores gradually decreased over the span of the treatment protocol. The control group showed either maintenance or slight worsening of depression and anxiety scores. -

Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 TARAL WAYNE :: NIALL Mcgrath & TIM TRAIN :: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) :: BRUCE GILLESPIE :: ABC CLASSICS Top 100 Scratch Pad 77 March 2011

Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 TARAL WAYNE :: NIALL McGRATH & TIM TRAIN :: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) :: BRUCE GILLESPIE :: ABC CLASSICS Top 100 Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 Based on the non-mailing comments section of *brg* 67 and 68, a fanzine for ANZAPA (Australia and New Zealand Amateur Publishing Association) written and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard St, Greensborough VIC 3088. Phone: (03) 9435 7786. Email: [email protected]. Member fwa. Website: GillespieCochrane.com.au Contents 3 Unsolved mysteries of the hereafter — by Taral Wayne 6 The brand new Scratch Pad poetry spot — by Niall McGrath and Tim Train 9 Ditmar’s best and favourite films of 2010 — by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) 15 Shining shores: Bruce Gillespie’s favourites 2010 — by Bruce Gillespie 36 ABC Classic 100 ten years on: 2010 — introduced by Bruce Gillespie Cover graphic — ‘Evening Phenomenon’ by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Cartoon p. 3: ‘Unsolved mysteries’ — by Taral Wayne 2 Unsolved mysteries of the hereafter by Taral Wayne I think some scholar, or someone who wanted to be mistaken for one, claimed that the translation from the Koran was wrong, and it wasn’t ‘seventy virgins’, but something like ‘seventy figs’, that a good Muslim could expect in Paradise, and that it only meant the blessed would be in the midst of plenty. I’m not sure I buy that. It was only 1500 years ago, and I don’t think Arabic then was so different from modern Arabic that millions of Arab Muslims make such an elementary mistake. But who knows ... maybe Allah really only did mean that the nearly arrived would be greeted with a plate of figs .. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 3-3-2021 2:00 PM Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario Lily Yosieph, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Orchard, Treena, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Science degree in Health and Rehabilitation Sciences © Lily Yosieph 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Community Health Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Other Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, Other Public Health Commons, Other Rehabilitation and Therapy Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Recommended Citation Yosieph, Lily, "Exploring the Mental Health Experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black Youth in London, Ontario" (2021). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7682. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7682 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This qualitative study explores the mental health experiences of African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) youth in London, Ontario, investigating how the factors of race, gender, culture, and place have shaped their perceptions and experiences of mental health. The data collection and analysis were conducted using a phenomenological approach and a critical lens informed by feminist, intersectionality, and critical race theories. These data illuminate the ways in which these young people’s attitudes toward mental health and help-seeking strategies are impacted by broader social constructs and community expectations, which they navigate and often resist in their everyday lives.