ABSINTHE – the HELL-DRINK THAT CAN PUT YOU in YOUR GRAVE1 by HAL POLLING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Absinthe Challenge

Anal Bioanal Chem (2014) 406:1815–1816 DOI 10.1007/s00216-013-7576-8 ANALYTICAL CHALLENGE The absinthe challenge Lucia D’Ulivo # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 We would like to invite you to participate in the Analytical “green fairy”, which included bohemian celebrities Vincent Challenge, a series of puzzles to entertain and challenge our van Gogh, Paul Gaugin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Charles Baude- readers. This special feature of Analytical and Bioanalytical laire, and Edgar Allan Poe. Consequently, absinthe was cele- Chemistry has established itself as a truly unique quiz series, brated in poems and paintings alike. Think of The Absinthe with a new scientific puzzle published every other month. Drinker by Manet (ca.1859), Degas (1876), or Picasso (1903), Readers can access the complete collection of published just to name a few artworks that further contributed to the problems with their solutions on the ABC homepage at popularity of absinthe. http://www.springer.com/abc. Test your knowledge and tease However, the popularity of absinthe took a sudden hit when your wits in diverse areas of analytical and bioanalytical it was singled out for several psychotic effects—seizures, chemistry by viewing this collection. hallucinations, or mental prostration—all of which were In the present ‘spirituous’challenge, the legendary absinthe summarized under the term absinthism [3]. In particular, is the topic. And please note that there is a prize to be won (a the monoterpene thujone was considered the active ingre- Springer book of your choice up to a value of €100). Please dient of absinthe. As a consequence, absinthe was banned read on… in Belgium in 1905, and this example was soon followed by Switzerland (1908), USA (1912), Italy (1913), France (1915), “At the Latin festival when four-horsed chariots race on and Germany (1923). -

New Bar Menu 2.0

7134 Main Street | Clifton, Virginia (703) 266-1623 T R U M M E R ’S trummersonmain.com Cocktail Menu EATS Sweets Milk Chocolate Mousse $12 banana, hazelnuts, mint “Carrot Cake” $11 cream cheese, pineapple, walnut Baked Triple Cream Belletoile Brie $15 Textures of Oranges $12 pu pastry, raspberries, almonds, sage sorbet, olive oil cake, sweetened ricotta, fennel Chocolate & Rum Tasting $25 3 artisanal chocolates & 3 rums to pair Tasting of Sorbets $10 3 scoops of house-made sorbet Red Wine Poached Pear $11 (please inquire with your server about fall spices, smoked custard, oats, maple, our sorbet’s as the selections change daily) NEW YORK CITY MEETS HISTORIC CHARM Trummer’s on Main combines a New York City experience with the charm of historic Clifton by stimulating your senses with seasonal and regionally sourced food, always-in- triguing unique cocktails and true European hospitality. Thursday is Burger Night. Come and expirience Chef Jon’s Noted Mixologist and co-owner Stefan Main boasts special Butcher Burger, only available Trummer leads the innovative craft the largest wine cellar in the on Thursdays, for only $7 Limited availability cocktail program, featuring a variety of Mid-Atlantic region, with the ability to large-format cocktails perfect for groups, hold more than 8,000 bottles. playful bottled libations and avorful Trummer’s glass-enclosed wine tasting garden-inspired mocktails. Trummer’s On room is complete with communal EATS Bar Food Indigo Blue Popcorn $8 Hand Cut True Fries & Parmesan $8 Chips & Vidalia Onion Dip $5 Crispy -

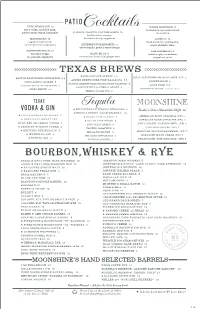

Liquor Menu 3.19

PATIO HARD LEMONADE 10 WHITE LIGHTNING 5 tito’s vodka, muddled mint, Cocktails homemade seasonal infused paula’s texas lemon, lemonade GOOD HEARTED OLD FASHIONED 12 moonshine buffalo trace, orange, MANHATTAN 13 drunken cherry, angostura SAZERAC 14 sagamore spirit rye, knob creek rye, peychaud’s, cocchi di torino, angostura SILVERMOON MARGARITA 8 sugar, absinthe rinse silver tequila, paula’s texas orange SOUTHERN BELLE 12 THE WATERLOO 9 wheatley vodka, BLIND MULE 9 waterloo gin, cucumbers, st. germain, raspberry moonshine, lime juice, ginger beer grapefruit juice <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< TEXAS BREWS <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< KARBACH LOVE STREET 5.5 AUSTIN EASTCIDERS PINEAPPLE 5.5 REAL ALE FIREMANS #4 BLONDE ALE 5 AUSTIN BEERWORKS FIRE EAGLE IPA 5.5 CIRCLE ENVY AMBER 5 SHINER BOCK 5 AUSTIN BEERWORKS PEARL SNAP PILSNER 5 CIRCLE BLUR TEXAS HEFE 5 LONE STAR 3.5 CONVICT HILL OATMEAL STOUT 6 CELIS WHITE 5.5 SEASONAL BREW MARKET PRICE FRESH COAST IPA 6 TEXAS Tequila MOONSHINE ★ VODKA & GIN PEPE ZEVADA Z TEQUILA REPOSADO 8 Dealer’s Choice Moonshine Flight 18 ★ ZEVADA FAMILY “GRAN RESERVA” 12 ★ TITO’S HANDMADE VODKA 7 ★ DULCE VIDA BLANCO 9 AMERICAN BORN ORIGINAL (TN) 8 ★ DEEP EDDY SWEET TEA, ★ DULCE VIDA AÑEJO 9 AMERICAN BORN APPLE PIE (TN) 8 RUBY RED OR LEMON VODKA 7 DON JULIO AÑEJO 9 STILL AUSTIN “DAYDREAMER” (TX) 8 ★ DRIPPING SPRINGS VODKA 8 TANTEO JALAPEÑO 8 CATDADDY SPICED (NC) 7 ★ DRIPPING SPRINGS GIN 8 MILAGRO SILVER 8 MIDNIGHT MOON STRAWBERRY (NC) 7 ★ WATERLOO GIN 8 MILAGRO REPOSADO 8 MIDNIGHT MOON PEACH (NC) 7 ★ ZEPHYR GIN 8 PATRON SILVER -

Modernization of the Labeling and Advertising

18704 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 64 / Thursday, April 2, 2020 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Table of Contents consolidating TTB’s alcohol beverage I. Background advertising regulations in a new part, 27 Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade CFR part 14. A. TTB’s Statutory Authority • Bureau B. Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Incorporate into the regulations Modernization of the Labeling and TTB guidance documents and current 27 CFR Parts 4, 5, 7, and 19 Advertising Regulations for Alcohol TTB policy, as well as changes in Beverages labeling standards that have come about [Docket No. TTB–2018–0007; T.D. TTB–158; C. Scope of This Final Rule through statutory changes and Ref: Notice Nos. 176 and 176A] II. Discussion of Specific Comments Received international agreements. and TTB Responses • Provide notice and the opportunity RIN 1513–AB54 A. Issues Affecting Multiple Commodities B. Wine Issues to comment on potential new labeling Modernization of the Labeling and C. Distilled Spirits Issues policies and standards, and on certain Advertising Regulations for Wine, D. Malt Beverage Issues internal policies that had developed Distilled Spirits, and Malt Beverages III. Regulatory Analyses and Notices through the day-to-day practical A. Regulatory Flexibility Act application of the regulations to the AGENCY: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and B. Executive Order 12866 approximately 200,000 label Trade Bureau, Treasury. C. Paperwork Reduction Act applications that TTB receives each IV. Drafting Information ACTION: Final rule; Treasury decision. year. I. Background The comment period for Notice No. SUMMARY: The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax 176 originally closed on March 26, and Trade Bureau (TTB) is amending A. -

Cocktail List

Sidecar AT PRINCE SOLMS INN House Cocktails Porch Cup……………………………………………… 10 Golden Hour…………………………………….. 12 Bourbon, Amaro, Lemon, & a touch of Sweet Tea Bourbon, Espresso, Amaro, & Cinnamon Highfalutin (hī’fah’loo͞ tn) ............................. 10 El Alma……………………………….... 11 Dark Rum, Montenegro, Allspice, & Strawberry Uruapan, Mint, Blackberry, Lime, Soda High Tea………………………………………..………. 10 Pink Panther……………………………………… 10 Gin, Benedictine, Earl Grey, Lemon, & Lavender Vodka, Watermelon, Lime, Ginger, & Soda Seasonal Sangria……………………………..…….. 9 El Cosmico…………………..……………………..10 Homemade Sangria with Seasonal Fruit Reposado, Mezcal, Chartreuse, & Passionfruit The Root of All Evil………..…….………………. 12 Scotland Yard………..…………………………... 15 Fernet Branca, Absinthe, Amaretto, Root Beer Blend of Scotch, Espresso, Sweet Cream Syrup, Sweet Cream, & Soda The Classics Sidecar…………………………. 12 Sazerac………………….. 10 404……………………………… 10 Cognac, Bauchant & Lemon Rye, Cognac & Absinthe Vodka, Aperol & Elderflower Black Manhattan…………… 12 Corpse Reviver #2…… 12 Papa Doble…………………… 10 Rye, Averna, Black Walnut Gin, Lillet Blanc, Lemon, Dark Rum, Luxardo, Lime & Bitters Bauchant, & Absinthe Grapefruit Strawberry Negroni……….. 9 French 77………………… 12 Tokyo Highball…………. 10 Gin, Campari, Vermouth, Gin, Lemon, Elderflower, Suntory Toki, Lemon, Tonic, & Strawberry & Sparkling Wine & Bitters High West Double Rye Old Fashioned……………………………… 13 Beer Wine Happy Hour Tuesday thru Friday, 4-6 * Pecos Amber………………… 7 *St. Supery Sauv. Blanc…... 8 Draft Wine/Beer………..……. 5 * Honey Blonde………………. 7 *Imagery Chardonnay…….. 8 Old Fashioned………………… 5 *So 5 Months Ago, PA……... 8 *Becker Tempranillo………. 8 Razzle Dazzle………………….. 5 *Doc Hoppiday, Hazy IPA… 8 *Line 39 Cabernet…………… 8 Strawberry Fitzgerald……… 5 Texas Cinnamon Ale……… 9 *Coutale Rose………………… 8 Margarita……………………….. 5 Tasty AF Nitro Stout……… 9 Liquid Light, SB……………...11 Daiquiri…………………………. 5 Macedon, Pinot Noir……....10 Mexican Stando……………. 7 Pessimist, Red Blend……….12 *Available During Happy Hour. -

Absinthe, Absinthism and Thujone – New Insight Into the Spirit's Impact on Public Health

32 The Open Addiction Journal, 2010, 3, 32-38 Open Access Absinthe, Absinthism and Thujone – New Insight into the Spirit's Impact on Public Health Dirk W. Lachenmeier*,1, David Nathan-Maister2, Theodore A. Breaux3, Jean-Pierre Luauté4 and Joachim Emmert5 1Chemisches und Veterinäruntersuchungsamt (CVUA) Karlsruhe, Weissenburger Strasse 3, D-76187 Karlsruhe, Germany 2Oxygenee Ltd, P.O. Box 340, Burgess Hill, RH15 5AP, UK 3Jade Liqueurs, L.L.C., 3588 Brookfield Rd, Birmingham, Alabama, 35226, USA 425 Rue de la République, 26100 Romans, France 5Perreystrasse 34, D-68219 Mannheim, Germany Abstract: Absinthe, a strong alcoholic aperitif, is notorious for containing the compound ‘thujone’, which has been commonly regarded as its ‘active ingredient’. It has been widely theorized that the thujone content of vintage absinthe made it harmful to public health, and caused the distinct syndrome absinthism, which was extensively described in the literature prior to the spirit’s ban in 1915. The interdisciplinary research presented in this paper shows that 1) absinthism cannot be distinguished from common alcoholism in the medical research literature of the time, and that 2) due to the physical chemistry of the distillation process, the thujone content of vintage absinthe was considerably lower than previously estimated and corresponds to levels generally recognized as safe, as proven by analyses of absinthes from the pre-ban era. Due to the re-legalization of absinthe in the European Union and more recently in the United States, potential public health concerns have re-emerged, not expressly based on worries about thujone content or absinthism, but on alcohol-related harm and youth protection issues, exacerbated by marketing strategies promoting absinthe using false and discredited claims pertaining to thujone and stubbornly persistant myths. -

Raising the Bar: Consumption, Gender, and the Birth of a New Public Drinking Culture Adam Blahut

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-12-2014 Raising the Bar: Consumption, Gender, and the Birth of a New Public Drinking Culture Adam Blahut Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Blahut, Adam. "Raising the Bar: Consumption, Gender, and the Birth of a New Public Drinking Culture." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/9 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adam Blahut Candidate History Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Andrew K. Sandoval-Strausz, Chairperson Dr. Larry Ball Dr. Paul Andrew Hutton Dr. Sharon Wood i RAISING THE BAR: CONSUMPTION, GENDER, AND THE BIRTH OF A NEW PUBLIC DRINKING CULTURE by ADAM BLAHUT B.A., HISTORY, MERCYHURST UNIVERSITY, 2002 M.A., SOCIAL SCIENCE, EDINBORO UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA, 2005 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY HISTORY The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2014 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Durwood Ball, Paul Andrew Hutton, and Sharon Wood for their advice and help while working with me on this dissertation. I would especially like to thank Andrew K. Sandoval-Strausz, my adviser and dissertation committee chair, who guided me through this project and made me a better historian in the process. -

Guide to Absinthe

The Guide to Absinthe Written by Laura Bellucci First Edition New Orleans, 2019 Printing by JS Makkos Design by Julia Sevin Special Thanks Ray Bordelon, Historian Ted Breaux Jessica Leigh Graves JS Makkos Alan Moss and all the other green-eyed misfits with a passion for our project Contents History of The Old Absinthe House . 5 Absinthe . 19 Absinthe and The Belle Époque . 29 Holy Herbs . 31 1 2 Le Poison Charles Baudelaire Le vin sait revêtir le plus sordide bouge Wine decks the most sordid shack D'un luxe miraculeux, In gaudy luxury, Et fait surgir plus d'un portique fabuleux Conjures more than one fabulous portal Dans l'or de sa vapeur rouge, In the gold of its red vapour, Comme un soleil couchant dans un ciel Like a sun setting in a nebulous sky . nébuleux. That which has no limits, with opium is L'opium agrandit ce qui n'a pas de yet more vast, bornes, It reels out the infinite longer still, Allonge l'illimité, Sinks depths of time and sensual delight . Approfondit le temps, creuse la volupté, Opium pours in doleful pleasures Et de plaisirs noirs et mornes That fill the soul beyond its capacity . Remplit l'âme au delà de sa capacité. So much for all that, it is not worth the Tout cela ne vaut pas le poison qui poison découle Contained in your eyes, your green eyes, De tes yeux, de tes yeux verts, They are lakes where my soul shivers and Lacs où mon âme tremble et se voit à sees itself overturned . -

Cocktail List

The Prohibition COCKTAIL LIST WWW.BOISDALE.CO.UK 2 | The Boisdale Cocktail List The Boisdale Cocktail List | 35 NAKED & FAMOUS How can you compete with an absolute classic like the Irish coffee? Different variations of coffee cocktails predate the now-classic Irish coffee by at least 100 years, and here we have created another variation! 20ml Naked Grouse Blended Malt Whisky 10ml Laphroaig 10yr 75ml Strong Americano 20ml Frangelico Cream Heat liqueur coffee glass and add Naked Grouse and Laphroaig 10yr. Add strong Americano coffee and stir. Top with Frangelico cream and grated nutmeg on top. The Prohibition Cocktail List £10.50 The temperance movement, which advocates moderating or entirely abstaining from alcohol, was popularised in Britain in the 19th cen- tury. The closest we came to prohibition was during the First World War, when pub hours became subject to licenses, the alcohol content of sprits was reduced and tax on alcohol was raised. Many breweries were also transformed into munitions factories and nationalised, limiting the supply of alcohol in Britain. Meanwhile in 1918, across the big pond, the 18th Amendment to the USA’s Constitution made it illegal to manufacture, transport and sell alcohol. The Boisdale cocktail menu draws inspiration from the era when illic- it liquor shops and drinking establishments fl ourished underground. 34 | The Boisdale Cocktail List The Boisdale Cocktail List | 3 L’ ALCOOL VOILA L’ENNEMI (Alcohol is the Enemy) In 1915, France had a Prohibition of its own by banning the drinking of Absinthe, which meant no more drinking of the New Orleans version of the classic whisky cocktail - The Sazerac. -

NFK Drink Menu.Pages

Haitian COFFEE LOCAL TEA Drip Coffee 3 Hot Tea 3 hot or iced chamomile holy basil Espresso 3 roasted barley Machiatto 3 seasonal soda yaupon Latte 4.5 Lavender Soda 4 Cappuccino 4.5 Iced Yaupon Tea 3 Lemon Balm- Mint Soda 4 add lemon balm syrup 1 add burnt honey, lavender, or Ginger Ale 4.5 dulce de leche 1 Ginger Kombucha 5 Cocktails RUM & BUCHA 11 Vitae golden rum, Blue Ridge ginger Kombucha, lemon balm jelly, lime basil MT. DEFIANCE ABSINTHE 12 VA made absinthe, served the traditional way with ice water dripped over sugar cubes WHITE RUSSIAN 11 Cirrus Vodka, Haitian espresso, Old Church Creamery whole milk, burnt honey SANGRIA 10 blended red & white wines, local peaches & apples, sparkling wine, Belle Isle moonshine SORBET FIZZ 8 choice of homemade cantaloupe, pear, watermelon or peach sorbet with Virginia Fizz sparkling wine ICED TODDY 12 Bowman Brother’s straight bourbon whiskey, burnt honey, lemon basil, chamomile iced tea OLD FASHIONED 10 Bowman Brother’s straight bourbon whiskey, Wapatoolie gastrique, lemon verbena syrup, bitters SAGE APPLE MOONTINI 11 apple syrup, sage, Belle Isle moonshine FRENCH 759 10 Virginia Fizz sparking wine, Catocin Gin, rosemary VIRGINIA beer & VIRGINIA WINEs IPA & DOUBLE IPA SPARKLING Blue Mountain / Hopwork Orange / American IPA 5 Thibaut Janisson Virginia Fizz NV 10 / 45 Commonwealth / Big Papi / Double IPA 10 Thibault Janisson Blanc de Chardonnay NV 75 Commonwealth / Papi Chulo / New England IPA 10 O’Connor / El Guapo / English IPA 5 WHITE O’Connor / Great Dismal / Black IPA 5 Ankida Ridge Rockgarden -

Cocktails Beer Shotz Free of Spirit Absinthe Fountain

cocktails beer shotz earl grey martini 2OZ ...................... $14 DRAUGHT | 16OZ prairie bombs .............................. $5 gin. earl grey syrup. lemon & whites o.t. brewing bush league pilsner .............. $8 rye. annex ale rootbeer PULL THE PIN kristian huselius 2OZ ...................... $14 5% | CALGARY, AB ........................ vodka. passionfruit liqueur. black tea syrup. lemon. cabin brewing super saturation NEPA ....... $8 normandy crushies $5 raspberries calvados. sweet vermouth. campari 6% | CALGARY, AB poor boy piña colada 2OZ .................. $14 SHAKEN & SERVED UP WITH ORANGE WEDGE dieu du ciel rosee d’hibiscus ................. $10 pisco. sweet vermouth. coconut milk. pineapple. french connection ......................... 5.9% | MONTREAL, QC $5 lime. angostura bitters cognac. amaretto the dandy brewing co. wild sour ale ....... $10 bruce banner 2OZ ........................... $14 SERVED ICE FUCKING COLD 7.3% | CALGARY, AB gin. white vermouth. snap peas. lime. sugar. crank stingers ..................................... $5 of black pepper crème de menthe. cognac john galt 2OZ ................................ $14 BOTTLES & CANS STINGER? DAMN NEAR KILLED HER chamomile white rum. cocchi americano. cachaça. miller high life american lager ............... $5 maraschino 4.6% | WISCONSIN, UNITED STATES | 355ML absinthe fountain [2 OR 4 PPL] dr. pepper old fashioned 2OZ .............. $14 four winds la maison wild saison ............ $7 rye. amaretto. dr. pepper syrup. angostura and 4.5% | DELTA, BC | 355ML cherry bitters -

Cocktails Beer Shotz Free of Spirit Absinthe Fountain

cocktails beer shotz earl grey martini 2OZ ...................... $14 DRAUGHT | 16OZ prairie bombs .............................. $5 gin. earl grey tea. lemon & whites tailgunner brewing co. czech pilsner ....... $9 rye. annex ale rootbeer PULL THE PIN kristian huselius 2OZ ...................... $14 4.5% | CALGARY, AB ........................ vodka. passionfruit liqueur. black tea syrup. lemon. establishment brewing sky rocket VI ipa .. $10 normandy crushies $5 raspberry calvados. sweet vermouth. campari 7.3% | CALGARY, AB poor boy piña colada 2OZ .................. $14 SHAKEN & SERVED UP WITH ORANGE WEDGE dieu du ciel rosee d’hibiscus ..................$11 pisco. sweet vermouth. coconut milk. pineapple. french connection ......................... 5.9% | MONTREAL, QC $5 lime. angostura bitters cognac. amaretto the dandy brewing co. wild sour ale ........$11 oaxaca flocka flame 2OZ ................... $14 SERVED ICE FUCKING COLD 7.3% | CALGARY, AB mezcal. tequila. adobo syrup. pineapple. lime stingers ..................................... $5 chamillionaire 2OZ ......................... $14 crème de menthe. cognac chamomile infused rum. cocchi americano. BOTTLES & CANS STINGER? DAMN NEAR KILLED HER cachaça. maraschino miller brewing co. “high life” lager ........ $5 4.6% | WISCONSIN, UNITED STATES | 355ML dr. pepper old fashioned 2OZ .............. $14 absinthe fountain [2 OR 4 PPL] rye. amaretto. dr. pepper syrup. angostura and four winds la maison wild saison ............ $7 cherry bitters 4.5% | DELTA, BC | 355ML st. george absinthe. sugar cubes. filtered water vitamin D 2.25OZ ............................ $14 the dandy brewing co. flip the bird ale ....... $8 “GOT TIGHT ON ABSINTHE LAST NIGHT. DID KNIFE TRICKS “ ...$60 bubbles. SunnyD. aperol 4.69% NICE | CALGARY, AB | 473ML dread pirate roberts 2OZ ................... $14 pei brewing raspberry sour ................. $10 rum. amaro. coffee. tonic. coconut syrup 5% | GAHAN, PEI | 473ML free of spirit cereal killer 2OZ ...........................