Caution, These Peppers Bite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descrizione Specie Aci Sivri X Jalapeno C.Annuum Anaheim C

Descrizione Specie Aci Sivri x Jalapeno C.annuum Anaheim C.annuum Ancho Poblano C.annuum Arcobaleno C.annuum Arlecchino C.annuum Atarado C.annuum Black Namaqualand C.annuum Black Pearl C.annuum Bob's Pickling C.annuum Bolivian Rainbow C.annuum Cacho de cabra C.annuum CAP 1546 C.annuum CH1 indiano C.annuum Chilhuacle Negro C.annuum Duemila C.annuum Explosive Ember C.annuum Fish C.annuum Goat's Weed C.annuum Heatwave C.annuum Hot M&M's C.annuum Indian PC-1 C.annuum Indian Red C.annuum J4 C.annuum Jalapeno Coyame C.annuum Jalapeno Dark Red C.annuum Jalapeno Farmer's Market Potato C.annuum Jalapeno Felicity C.annuum Jalapeno Goliath C.annuum Jalapeño grosso C.annuum Jalapeño liscio C.annuum Jalapeno Mammouth C.annuum Joe's Long Cayenne C.annuum Kashmiri Mirch C.annuum Kroatina C.annuum Lanterna de Foc C.annuum Lazzaretto Abruzzese C.annuum Li Black C.annuum Little Elf C.annuum Masquerade C.annuum Maui Purple C.annuum Mauritius C.annuum Naga Jolokia Purple C.annuum Naga Khorika C.annuum Napoli C.annuum Naso di cane C.annuum Numex Bailey Pequin C.annuum Numex Big Jim C.annuum Numex Sandia C.annuum Numex Sunrise C.annuum Numex Sunset C.annuum Numex twilight C.annuum Peperone di Capriglio Giallo C.annuum Pimenta de Padron C.annuum Purple UFO C.annuum Satan's Kiss C.annuum SBS Purple C.annuum Scozzese C.annuum Serrano del Sol C.annuum Short Yellow Tabasco C.annuum Stefania C.annuum Thai Orange C.annuum Topepo Piccante C.annuum Corno Ungherese C.annuum Variegato C.annuum Vietato C.annuum Yalova Charleston C.annuum Yemen Nord Arancio C.annuum Yemen -

Pepper Joes Seeds 2017.Pdf

Maynard, MA 01754 300. Suite St., Parker 141 16 NEW HOT NEW HOT 16 THIS YEAR THIS Reapers Festival PEPPERS Wow! Not just the legendary Carolina Reaper, but now we have more in the family! If you are a Reaper fan, get ready! Carolina Reaper Grow the legendary Guinness Book of World Records hottest pepper on the planet. This is the REAL deal, from the original strain of award-winning peppers. 1,569,000 Scoville Heat Units. $9.99 (10+ seeds) Chocolate Reaper Mmmm… smoky! This delicious hot pepper tastes as good as the classic, but with the hint of a smoky taste up front. It is still being bred out for stabil- ity, but worth the taste! $9.99 (10+ seeds) of 7342companies reviewed and 30 “Top a out Company” Joe’s #1 in Pepper Seeds Dave’s Garden Ranks Pepper Yellow Reaper Try this beauty with grilled seafood! It has a fruity flavor paired with loads of heat. We are still growing this pepper out, but wanted to bring it to you without delay! US POSTAGE Sudbury, MA Sudbury, Permit No 3 $9.99 (10+ seeds) STD PRSRT PAID About Pepper Joe’s Butch “T” Trinidad ScorpionOUR W e a#3re the expWe’reerts in thrilledHot Pe topp haveer Se thiseds .# 3 “WORLD’S HOTTEST PEPPER. It set a Guinness Book PLEDGEof World Record N THS EAR - 1 SCREAMING Since 1989, Pepperearly Joe’s in 2011has found, at 1,450,000 grown, Scoville Units. WOW! NEHOT oetos EPPS and enjoyed superThat’s hot peppersa lot of fromheat. all This over is a very exclusive pepper the world. -

Reimer Seeds Catalog

LCTRONICLCTRONIC CATALOGCATALOG Drying Hot Peppers HP320‐20 ‐ Achar Hot Peppers HP321‐10 ‐ Aci Sivri Hot Peppers 85 days. Capsicum annuum. Open 85 days. Capsicum annuum. Open Pollinated. The plant produces good yields Pollinated. The plant produces good yields of 3 ¼" long by 1" wide hot peppers. Peppers of 7 ½" long by ½" wide Cayenne type hot are hot, have medium thin flesh, and turn peppers. Peppers are medium hot, have from green to deep red when mature. The medium thin flesh, and turn from light plant has green stems, green leaves, and yellowish‐green to red when mature. The white flowers. Excellent for pickling and plant has green stems, green leaves, and seasoning spice. A variety from India. United white flowers. Excellent drying, pickling, and States Department of Agriculture, PI 640826. seasoning powder. An heirloom variety from Scoville Heat Units: 27,267. Turkey. HP21‐10 ‐ Afghan Hot Peppers HP358‐10 ‐ African Fish Hot Peppers 85 days. Capsicum annuum. Open 85 days. Capsicum annuum. Open Pollinated. The plant produces good yields Pollinated. The plant produces good yields of 3" long by ½" wide Cayenne hot peppers. of 1 ½" long by ½" wide hot peppers. Peppers are very hot, have medium thin Peppers are medium‐hot, have medium thin flesh, and turn from green to red when flesh, and turn from cream white with green mature. The plant has green stems, green stripes, to orange with brown stripes, then leaves, and white flowers. Excellent for to red when mature. The plant has Oriental cuisine and for making hot pepper variegated leaves. An African‐American flakes and seasoning spice powder. -

Pepper List 2020

Pepper List 2020 We carry an excellent selection of locally-grown sweet and hot peppers. Peppers are a fun challenge for Pacific Northwest gardeners, and can be very rewarding. With so many colors, shapes, and flavors to choose from, some gardeners like to try at least one new variety each year. Growing Peppers The key to success with peppers is maximizing sunlight and heat. Pepper plants should be kept indoors or in greenhouses until nighttime temperatures are above 50-60°F. Even then, they benefit from additional protection. Try building a high tunnel out of clear plastic, or plant them in containers near a south or west-facing wall that reflects heat. Peppers can thrive in raised beds or containers, provided that they are in a full-sun location and well-fertilized. For container planting, use potting soil with added organic fertilizer. In raised beds, use rich, well-drained soil and organic fertilizer. Whether growing in the ground or in containers, water thoroughly rather than often. Let the soil dry to about 1-2 inches down before watering. To produce the spiciest and most flavorful hot peppers, provide the warmest soil and air temperatures possible and withhold water once the fruit begins to ripen. Our Pepper Varieties Several of the listings below are popular categories rather than specific varieties. You’ll see the phrase, “rotating selection” beneath these lines. The particular varieties will depend on weekly availability from our local growers, but we’ll keep a selection of these classic favorites in stock. Other listings are diverse heirloom varieties, each with their own unique qualities. -

Warm Weather Vegetables and Fruits Availability ($3.95/4” Pot, Unless Otherwise Specified)

Warm Weather Vegetables and Fruits Availability ($3.95/4” Pot, unless otherwise specified). Please call to order. PEPPERS: Sweet: Altino Sweet Paprika (heirloom pepper) Banana Supreme (early-fruiting, banana-shaped sweet pepper) Bell – California Wonder (green bell pepper) Bell – Valencia (orange bell pepper) Bell – Glow (orange mini-bell, lunchbox pepper) Bell – Golden Summer (yellow bell pepper) Bell – Lilac (purple bell pepper) Bell – Red Knight (red, hybrid, disease-resistant bell pepper) Carmen (red corno di toro Italian frying pepper) Cubanelle (sweet Italian frying pepper) Escamillo (yellow corno di toro Italian frying pepper) Shishito (Japanese frying pepper; end resembles a lion’s head) Hot: Altino (a long, cayenne-type of hot pepper used for chili flakes) Anaheim (mild-heat chili pepper) Ancho-Poblano (ancho is a mild chili pepper; dried it is known as a poblano pepper) Apocalypse Scorpion (oily, red super-hot chili pepper) Apocalypse Scorpion Chocolate (appealing brown super-hot chili pepper) Basket of Fire (small multi-colored pepper that is both edible and ornamental) Bhut Jolokia – Chocolate (very hot dark brown chili pepper; 125x hotter than a jalapeno) Bhut Jolokia – Neyde Black (dark purple to black super-hot variation of the Bhut Jolokia pepper) Bhut Jolokia – Red (extremely hot red pepper; once certified as the hottest pepper in the world) Buena Mulata (pepper that starts out as violet and very hot, ripening to red with less heat) Caribbean Red Hot (extremely hot -

Hodnocení a Změny Různých Odrůd Chilli Papriček a Výrobků Z Nich V Průběhu Úchovy

Hodnocení a změny různých odrůd chilli papriček a výrobků z nich v průběhu úchovy Bc. Gabriela Gaubová Diplomová práce 2020 PROHLÁŠENÍ AUTORA DIPLOMOVÉ PRÁCE Beru na vědomí, ţe: diplomová práce bude uloţena v elektronické podobě v univerzitním informačním systému a dostupná k nahlédnutí; na moji diplomovou práci se plně vztahuje zákon č. 121/2000 Sb. o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon) ve znění pozdějších právních předpisů, zejm. § 35 odst. 3; podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona má Univerzita Tomáše Bati ve Zlíně právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o uţití školního díla v rozsahu § 12 odst. 4 autorského zákona; podle § 60 odst. 2 a 3 autorského zákona mohu uţít své dílo – diplomovou práci nebo poskytnout licenci k jejímu vyuţití jen s předchozím písemným souhlasem Univerzity Tomáše Bati ve Zlíně, která je oprávněna v takovém případě ode mne poţadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které byly Univerzitou Tomáše Bati ve Zlíně na vytvoření díla vynaloţeny (aţ do jejich skutečné výše); pokud bylo k vypracování diplomové práce vyuţito softwaru poskytnutého Univerzitou Tomáše Bati ve Zlíně nebo jinými subjekty pouze ke studijním a výzkumným účelům (tj. k nekomerčnímu vyuţití), nelze výsledky diplomové práce vyuţít ke komerčním účelům; pokud je výstupem diplomové práce jakýkoliv softwarový produkt, povaţují se za součást práce rovněţ i zdrojové kódy, popř. soubory, ze kterých se projekt skládá. Neodevzdání této součásti můţe být důvodem k neobhájení práce. Prohlašuji, ţe jsem diplomové práci pracoval samostatně a pouţitou literaturu jsem citoval. V případě publikace výsledků budu uveden jako spoluautor. ţe odevzdaná verze diplomové práce a verze elektronická nahraná do IS/STAG jsou obsahově totoţné. -

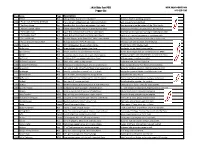

2020 Hugo Feed Mill Pepper List Type Description

2020 Hugo Feed Mill www.hugofeedmill.com Pepper List 651-429-3361 New Name Type Description 09154 Hot A long, skinny Thai ¼" x 2" red pepper. Grows in clusters pointing upwards. 2018 7 Pot B. Gum X Pimenta de Neyde Hot Fiery Hot with a Bleeding Stem. Salmon to Red skin with ocassional purple blush. 7 Pot Brain Strain Hot Scorching hot, fruity flavored peppers. High yield. Said by some to be the hottest of the 7 Pot family. 7 Pot Brain Strain Yellow Hot Yellow version of the Red Brain Strain but less heat Originally from Trinidad, pineapple flavor, w/ 7 Pot heat 7 Pot Bubble Gum Hot Super Hot w/ floral smell and fruity undertones Red fruit w/ stem and cap ripening to bubblegum color 7 Pot Bubble Gum* Hot Super Hot w/ floral smell and fruity undertones Red fruit w/ stem and cap ripening to bubblegum color 7 Pot Lava Brown Hot Another Pepper in the Super Hots. Heat is remarkable Smokey fruity, brown pepper with the scorpion look 7 Pot Lave Brown Variant Red Hot Moruga Scorpion X 7 Pot Primo cross Morurga look with a stinger, extremely hot 2020 Aji Amarillo Hot 4-5" long pepper. Deep yellow/orange. Fruity flavor with intense heat. Aji Perrana Hot Large Aji type orange pepper from Peru. Similar to an Aji Amarillo but smaller. Aji Chombo Hot Robust rounded red scorcher from Panama. Scotch bonnet type fruit w/ sweet flavor then BAM! Aji Cito Hot Awesome producer of beautiful torpedo shaped peppers. Peruvian pepper, with 100,000 SHU and a hint of citrus. -

Hot Chili Chili Tool Oa., Styrke & Scoville – 3 – Rev

Hot Chili Chili tool oa., Styrke & Scoville – 3 – rev. 1.2 Stor liste med relativ styrke og Scoville værdi (..eller den lille gruppe oversigt med kendte chili) Styrke Navne Scoville Noter ▪ Ren Capsaicin 16,000,000 12 ▪ Carolina Reaper 2,200,000 ▪ Trinidad Moruga Scorpion 2,009,231 ▪ ▪ 7 Pot Douglah 1,853,396 10++++ til 12 ▪ Trinidad Scorpion Butch T 1,463,700 ▪ Naga Viper Pepper 1,382,118 ▪ 7 Pot Barrackpore 1,300,000 ▪ 7 Pot Jonah 1,200,000 ▪ 7 Pot Primo 1,200,000 ▪ New Mexico Scorpion 1,191,595 ▪ Infinity Chili 1,176,182 ▪ Bedfordshire Super Naga 1,120,000 ▪ ▪ Dorset Naga chili 1,100,000 ▪ Naga Jolokia 1,100,000 ▪ Naga Morich 1,100,000 ▪ Spanish Naga Chili 1,086,844 ▪ 7 Pot Madballz 1,066,882 ▪ Bhut Jolokia chili 1,041,427 ▪ Chocolate Bhut Jolokia 1,001,304 ▪ 7 Pot Brain Strain 1,000,000 ▪ Bhut Jolokia Indian Carbon 1,000,000 ▪ Trinidad Scorpion 1,000,000 ▪ Raja Mirch 900,000 ▪ Habanaga chili 800,000 ▪ Nagabon Jolokia 800,000 ▪ Red Savina Habanero 580,000 10++++ Chili Home Side 1/12 Hot Chili Chili tool oa., Styrke & Scoville – 3 – rev. 1.2 10+++ og 10++++ ▪ Fatalii 500,000 10++++ ▪ Aji Chombo 500,000 ▪ Pingo de Ouro 500,000 ▪ Aribibi Gusano 470,000 ▪ Caribbean Red Habanero 400,000 ▪ Chocolate Habanero 350,000 10++++ ▪ Datil chili 350,000 10++++ ▪ Habanero 350,000 ▪ Jamaican Hot chili 350,000 ▪ Madame Jeanette chili 350,000 ▪ Rocoto chili 350,000 ▪ Scotch Bonnet 350,000 10+++ ▪ Zimbabwe Bird Chili 350,000 ▪ Adjuma 350,000 ▪ Guyana Wiri Wiri 350,000 10+++ ▪ Tiger Paw 348,634 ▪ Big Sun Habanero 325,000 ▪ Orange Habanero 325,000 9 og 10+++ ▪ Mustard Habanero 300,000 ▪ Devil’s Tongue 300,000 10++++ ▪ Orange Rocoto chili 300,000 10++ ▪ Paper Lantern Habanero 300,000 ▪ Piri Piri 300,000 8-10 ▪ Red Cheese 300,000 ▪ Red Rocoto 300,000 10++ ▪ Tepin chili 300,000 ▪ Thai Burapa 300,000 ▪ White Habanero 300,000 9-10 ▪ Yellow Habanero 300,000 ▪ Texas Chiltepin 265,000 ▪ Pimenta de Neyde 250,000 ▪ Maori 240,000 ▪ Quintisho 240,000 Chili Home Side 2/12 Hot Chili Chili tool oa., Styrke & Scoville – 3 – rev. -

Hot Pepper (Capsicum Spp.) – Important Crop on Guam

Food Plant Production June 2017 FPP-05 Hot Pepper (Capsicum spp.) – Important Crop on Guam Joe Tuquero, R. Gerard Chargualaf and Mari Marutani, Cooperative Extension & Outreach College of Natural & Applied Sciences, University of Guam Most Capsicum peppers are known for their spicy heat. Some varieties have little to no spice such as paprika, banana peppers, and bell peppers. The spice heat of Capsicum peppers are measured and reported as Scoville Heat Units (SHU). In 1912, American pharmacist, Wilbur Scoville, developed a test known as the, Scoville Organoleptic Test, which was used to measure pungency (spice heat) of Capsicum peppers. Since the 1980s, pungency has been more accurately measured by high-performance liquid chromatography Source: https://phys.org/news/2009-06-domestication- (HPLC). HPLC tests result in American Spice Trade capsicum-annuum-chile-pepper.html Association (ASTA) pungency units. ASTA pungency Introduction units can be converted to SHU. Table 2 displays Sco- Hot pepper, also known as chili, chilli, or chile pepper, ville Heat Units of various popular Capsicum peppers is a widely cultivated vegetable crop that originates (Wikipedia, 2017). from Central and South America. Hot peppers belong to the genus Capsicum. There are over 20 species under the genus Capsicum. There are five major domesticated species of peppers that are commercially cultivated (Table 1), and there are more than 50,000 varieties. Fig. 1 depicts a unqiue, citrus-flavored variety of Capsicum baccatum hot pepper, known as Lemon Drop (aji-type), popular for seasoning in Peru (Wikipedia, 2017). Table 1. The five major domesticated Capsicum species of pepper with examples of commonly known types of pepper. -

Peppers-A Photographic Guide

PEPPERSA Photographic Guide by Daniel Beim Introduction Peppers: Culinary proof that humans are a terrifying species that loves to defy natural selection and push the boundaries of their stomachs and of nature. A perfect example of this is the fact that someone saw the Carolina Reaper – the current hottest pepper in the world – and thought it would be a good idea to add some of it to a beer, ignoring the fact that anything but milk spreads the burn of capsaicin. It never ceases to amaze me, and though I don’t quite have the stomach for it, I can’t say that I blame people for eating them. For the unaccustomed it’s all about the thrill, and thanks to one too many days spent browsing YouTube, I can certainly say that watching people try to explain things after chomping a pepper is disturbingly entertaining. More important than the entertainment factor though is the fact that peppers are very aesthetically pleasing vegetables; Edward Weston’s Pepper No. 30 would not have been such a hit if they were boring, right? With this in mind, I set out to get my hands on a variety of peppers to see how each type looked both inside and out. Thanks to the wonderful vendors at the City of Rochester Public Market, I was able to gain samples ranging from sweet Bell Peppers, all the way up to the dreaded Bhut jolokia (or Ghost pepper) and give them a little studio time to take a look under their skins. How to Measure Pepper Heat Peppers and products with their derivatives typically have their heat measured in “Scoville Heat Units (SHU)” using the “Scoville scale,” developed by Wilber L. -

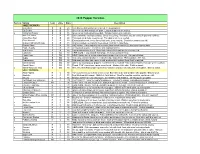

2020 Pepper Varieties

2020 Pepper Varieties Heirloom Variety heat style Days Description SWEET PEPPERS Better Bell S B 65 Very blocky, thick walled, green to red. Heavy producer. Big Bertha S B 71 Green to red, thick walled. 24" plant. Largest pepper on the market. x California Wonder S B 76 Green to red thick walled sweet bell. Tomato mosaic virus resistant. Mini Bell Yellow S B 57 Sweet mini-bell, very high yeilding. Great for stuffing. The mini's you are seeing in gourmet markets. Jingle Bells Red S B 60 High yield, small bells, green to red. For salad or stir fry or stuffed. Giant Marconi S B 63 Exceptionally sweet smoky flavor, high yield, great roasted. Good short season non bell. Golden California Wonder S B 73 Glorious golden color adorns these sweet, crunchy, 4-lobed bells. Orange Blaze S B 65 AAS winner. Early maturing bell w/ sweet flavor which reaches it's best at full orange color. x Purple Beauty S B 70 A truly purple pepper. Thick flesh and highly productive. Red Beauty S B 68 High producing sweet bell. Shiny fruit matures from dark green to intense red. Cubanelle S SO 68 HEIRLOOM. Large smooth frying type. Delicious pungent flavor. Candy Cane S SO 70 NEW! Unique green-yellow striped snack pepper that turns red. Variegated foliage Gypsy S SO 60 Very early, compact producer. 3-lobed wedge shaped fruit. Plants produce 30+ fruit. Peperoncino S SO 62 Mild wrinkled Italian type, green to red, medium thick walled. Great fresh or pickled. Sweet Banana S SO 67 One of our most popular peppers, excellent fresh or cooked! Thick walled. -

Capsicum Species & Varieties

*DAYS TO MATURITY 2020 HOT PEPPER VARIETIES HEIR- NAME FRUIT DETAILS LOOM? *DTM ACI SIVRI Old Turkish variety can be mild to burning hot. Productive for Northern gardens producing up to fifty 5- 90 CAYENNE 9” fruit. AJI RICO Red 3-4” fruits have a warm heat with a refreshing citrus flavor. Great fresh, cooked or in salsa. Aslo 70 dries well making an excellent spicy paprika. ANAHEIM CHILI 8” long, tapered, bright green fruits. Ripens to red. Mild flavor. 77 ANAHEIM Same as the green Anaheim chilies you find in the grocery store, but better because you'll get to eat them COLLEGE 64 fresh and full of flavor! Anaheim College 64 yields 6-10 tasty fruit per plant, each 6-8 inches long. The 74 thick-walled conical fruit turn from green to red, mild to medium heat. ANCHO Your chili rellenos will be the talk of the neighborhood! These fruit are thick-walled, turn from green to MAGNIFICO bright red, and possess a classic Poblano flavor. Plants produce high yields of 4 ½ - 6 ½ inch long 70 peppers that are one of the earliest Anchos on the market. ANCHO TIBURON Produces heavy yields of 12” long hot peppers with sweet thick flesh. Moderately hot. Traditionally used 85 for chile rellenos. BHUT JOLOKIA This fiery pepper is rumored to be the hottest in the world. The wrinkled, 2½ inch by 1 inch fruits turn 80-85 (GHOST PEPPER) red when mature. Handle with care! BIG JIM ANAHEIM Tapered long fruits ripen green to red. Compact yet prolific plants yield large peppers great for roasting.