The Prince of Utopia, Thomas More's Utopia and the Low Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translated and Edited Publications

Translated and edited publications There are nearly 250 items in this list, including co-translations and revised editions. Editing and translations from German and French are indicated, otherwise the listed publications are translations from Dutch. Katrijn Van Bragt and Sven Van Dorst, Study of a Young Woman: An exceptional glimpse into Michaelina Wautier’s studio (1604–1689) (Phoebus Focus 19) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Leen Kelchtermans, Portrait of Elisabeth Jordaens: Jacob Jordaens’ (1593–1678) tribute to his eldest daughter and country life (Phoebus Focus 18) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Nils Büttner, A Sailor and a Woman Embracing: Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and modern painting (Phoebus Focus 16) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Dina Aristodemo, Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi: Lodovico Guicciardini and the Low Countries (Phoebus Focus 15) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Timothy De Paepe, Elegant Company in a Garden: A musical painting full of sixteenth-century wisdom (Phoebus Focus 9) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Chris Stolwijk and Renske Cohen Tervaert, Masterpieces in the Kröller- Müller Museum (Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum, 2020) Maximiliaan Martens et al., Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution (Antwerp: Hannibal, 2020). All the translations from Dutch. Nienke Bakker and Lisa Smit (eds.), In the Picture: Portraying the Artist (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2020) Hans Vlieghe, Apollo on His Sun Chariot (Phoebus Focus 8) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2019) Joris Van Grieken, Maarten Bassens, et al., Bruegel in Black & White: The World of Bruegel (Antwerp: Hannibal, 2019). Translation of all but one of the texts. Bert van Beneden (ed.) From Titian to Rubens: Masterpieces from Antwerp and other Flemish Cities (Ghent: Snoeck, 2019); exhibition catalogue Venice, Palazzo Ducale. -

Books Received April–June 2014

Renaissance Quarterly Books Received April–June 2014 Acres, Alfred. Renaissance Invention and the Haunted Infancy . Turnhout: Brepols, 2013. 310 pp. €100. ISBN: 978-1-905375-71-4. Adams, Jonathan. A Maritime Archaeology of Ships: Innovation and Social Change in Medieval and Early Modern Europe . Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2013. xiii + 250 pp. £29.95. ISBN: 978-1- 84217-297-1. Albertson, David. Mathematical Theologies: Nicholas of Cusa and the Legacy of Thierry of Chartres . Oxford Studies in Historical Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. xii + 484 pp. $74. ISBN: 978-0-19-998973-7. Anderson, Michael Alan. St. Anne in Renaissance Music: Devotion and Politics . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. xvii + 346 pp. $99. ISBN: 978-1-107-05624-4. Baert, Barbara. Nymph: Motif, Phantom, Affect: A Contribution to the Study of Aby Warburg (1866–1929) . Studies in Iconology 1. Leuven: Peeters, 2014. 134 pp. €34. ISBN: 978-90-429- 3065-0. Balizet, Ariane M. Blood and Home in Early Modern Drama: Domestic Identity on the Renaissance Stage . Routledge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture 25. New York: Routledge, 2014. xii + 198 pp. $125. ISBN: 978-0-415-72065-6. Balserak, Jon. John Calvin as Sixteenth-Century Prophet . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. xiii + 208 pp. $85. ISBN: 978-0-19-870325-9. Banker, James R. Piero della Francesca: Artist and Man . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. xxvi + 276 pp. $39.95. ISBN: 978-0-19-960931-4. Barrie, David. Sextant: A Young Man’s Daring Sea Voyage and the Men Who Mapped the World’s Oceans . New York: William Morrow, 2014. -

Wie Was Pieter Gillis ?

Wie was Pieter Gillis ? Op 28 november 1509 werd Pieter Gillis stadsgriffier te Antwerpen. Hij bleef 23 jaar in functie tot zijn schoonzoon, Pieter de Coelenare, op 29 november 1532 zijn taken overnam. Tot in 1530 bewoonde Pieter Gillis het huis van zijn vader, De Biecorf, gelegen op de Kiekenmarkt (thans Eiermarkt) te Antwerpen. De laatste jaren van zijn leven woonde hij in het Werfstraatje (thans Heilige-Geeststraat) waar zijn derde vrouw Kathelijne Draeckx het vruchtgebruik van een huis had. Na zijn opleiding in de Antwerpse papenschool vertrok Pieter al op jonge leeftijd (14 jaar) naar de universiteit van Orléans. Daar was een gerenommeerde rechtsacademie waar heel wat Brabantse juristen gevormd werden ter voorbereiding op een functie in de stadsadministratie. Maar Pieter slaagde er aanvankelijk niet in zich door te zetten. Was hij nog te jong? Was zijn opleiding ontoereikend? Feit is dat hij terug naar huis kwam om corrector te worden in de drukkerij van Dirk Martens. In diens atelier leerde hij Erasmus kennen, van wie Martens in februari 1503 een verzamelboek, ‘Lucubratiunculae aliquot’, uitgaf en een jaar later een ‘Panegyricus’, een lofrede op Filips de Schone. Voor dat laatste werk kwam Erasmus zelf naar Antwerpen: de opdrachtbrief bij de lofrede is geschreven ‘ex officina chalcographica’. Pieter werd een vertrouweling van Erasmus en op aansporing van de Rotterdamse humanist ondernam hij een tweede poging om een titel te verwerven. In juni 1504 schreef ‘Petrus Egidii filius Nicholai Egidii de Antverpia’ zich in als student te Leuven, waarschijnlijk weer aan de rechtsfaculteit. Hij combineerde zijn studies met correctiewerk voor Dirk Martens en vanaf 1509 met zijn opdracht als griffier. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

In Search of Utopia Art and Science in the Era of Thomas More

IN SEARCH OF UTOPIA ART AND SCIENCE IN THE ERA OF THOMAS MORE Jan Van der Stock IN SEARCH OF UTOPIA ART AND SCIENCE IN THE ERA OF THOMAS MORE Jan Van der Stock f o r v e r o n i q u e vandekerchove (1 9 6 5 – 2 0 1 2) Chief Curator of M-Museum Leuven and initiator of this exhibition f o r j a n r o e g i e r s (1944–2013) Emeritus Professor of History at the KU Leuven and a source of inspiration for this exhibition Contents Catalogue AUTHORS UTOPIA OF THOMAS MORE (1516) A Golden Book from Leuven Conquers the World [CVD] Chet Van Duzer 9 Foreword 73 Utopia the Book, in Leuven and the Low Countries [CK] Cecile Kruyfhooft JAN PAPY [DVH] Daan van Heesch 13 In Search of Utopia – The Exhibition [EDP] Els De Palmenaer JAN VAN DER STOCK 74 cat. 1–8 [EM] Elizabeth Morrison [EV] Emmanuelle Vagnon 21 Europe-America-Utopia: Visions of an Ideal World 103 Editions and Translations of Utopia 1516 –1750 [HI] Hannah Iterbeke in the Sixteenth Century MARCUS DE SCHEPPER [JH] Jan Herman HANS COOLS [JL] Jeroen Luyckx 104 cat. 9–2 [JLB] Jens Ludwig Burk 31 Thomas More, Utopia and Leuven: [JP] Jan Papy Tracing the Intellectual and Cultural Context 129 Utopia and European Humanism [JS] Jochen Sander JAN PAPY JAN PAPY [JVG] Joris Van Grieken [KB] Koenraad Brosens 41 Erotic Utopia: the ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ 130 cat. 13a–19 [KS] Katharina Smeyers in Context [KVC] Koenraad Van Cleempoel PAUL VANDENBROECK [LC] Lorne Campbell [LMM] Linda M. -

NLN Fall 2017.Pdf (235.5Kb)

123 seventeenth-century news NEO-LATIN NEWS Vol. 65, Nos. 3 & 4. Jointly with SCN. NLN is the official publica- tion of the American Association for Neo-Latin Studies. Edited by Craig Kallendorf, Texas A&M University; Western European Editor: Gilbert Tournoy, Leuven; Eastern European Editors: Jerzy Axer, Barbara Milewska-Wazbinska, and Katarzyna Tomaszuk, Centre for Studies in the Classical Tradition in Poland and East- Central Europe, University of Warsaw. Founding Editors: James R. Naiden, Southern Oregon University, and J. Max Patrick, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Graduate School, New York University. ♦ ♦ Geschichte der neulateinische Literatur: Vom Humanismus bis zur Gegenwart. By Martin Korenjak. Munich: C. H. Beck, 2016. 304 pp. €26.95. As a number of people have noticed, Neo-Latin as a discipline seems to have reached a crossroads. After a hiatus of almost forty years, during which the field was well served by Josef IJsewijn and Dirk Sacré’s Companion to Neo-Latin Studies (Leuven, 1977), three new handbooks have recently appeared in rapid succession: Brill’s Encyclopaedia of the Neo-Latin World, ed. Philip Ford, Jan Bloemendal, and Charles Fantazzi (Leiden, 2014); The Oxford Handbook of Neo- Latin, ed. Sarah Knight and Stefan Tilg (Oxford, 2015); and A Guide to Neo-Latin Literature, ed. Victoria Moul (Cambridge, 2017). At the same time, my “Recent Trends in Neo-Latin Studies,” Renaissance Quarterly 69 (2016): 617–29 appeared, signifying that Neo-Latin has received the same recognition that English, history, and German have in the journal of record for the period in which the greatest amount of Neo-Latin literature was produced. -

A History of the Vikings

A HISTORY OF THE VIKINGS PLAT E I THE PIRAEUS LION: NOW IN VENICE A GREEK CARVING WITH RUNIC INSCRIPTION ON FLANKS Height about 12 feet. See p. 176. A HISTORY OF THE VIKINGS T. D. KENDRICK FRANK CASS & CO. LTD. 1 9 6 8 Published by FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0 X 14 4RN by arrangement with Methuen & Co. Ltd. First edition 1930 New impression 1968 Transferred to Digital Printing 2006 ISBN 0- 7146- 1486-6 (hbk) Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent PREFACE HE vikings are still awaiting their English historian. I do not mean that there is no full account of their doings in Great Britain, for of course there are many excellent books by Englishmen dealing with this special aspect of viking T history, and among them are the well-known works of Palgrave, Freeman, Oman, and Hodgkin ; I mean that there is no sub- stantial book in English exclusively devoted to the vikings and setting forth the whole of their activities not only in the west and the far north, but in the east and south-east as well ; for Paul du Chaillu’s 1 long and discursive book The Viking Age can hardly rank as serious history, interesting and informative though it is, and I am confident that Professor Allen Mawer would want his admirable little work The Vikings to be regarded only as a brief and introductory sketch. -

Heritage Days 14 & 15 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS 14 & 15 SEPT. 2019 A PLACE FOR ART 2 ⁄ HERITAGE DAYS Info Featured pictograms Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Urban.brussels (Regional Public Service Brussels Urbanism and Heritage) Clock Opening hours and Department of Cultural Heritage dates Arcadia – Mont des Arts/Kunstberg 10-13 – 1000 Brussels Telephone helpline open on 14 and 15 September from 10h00 to 17h00: Map-marker-alt Place of activity 02/432.85.13 – www.heritagedays.brussels – [email protected] or starting point #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers M Metro lines and stops reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. T Trams Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not B Busses bring rucksacks or large bags. “Listed” at the end of notices indicates the date on which the property described info-circle Important was listed or registered on the list of protected buildings or sites. information The coordinates indicated in bold beside addresses refer to a map of the Region. A free copy of this map can be requested by writing to the Department sign-language Guided tours in sign of Cultural Heritage. language Please note that advance bookings are essential for certain tours (mention indicated below the notice). This measure has been implemented for the sole Projects “Heritage purpose of accommodating the public under the best possible conditions and that’s us!” ensuring that there are sufficient guides available. -

Heritage Days Recycling of Styles 17 & 18 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS RECYCLING OF STYLES 17 & 18 SEPT. 2016 Info Featured pictograms Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Regional Public Service of Brussels/Brussels Urban Development Opening hours and dates Department of Monuments and Sites a CCN – Rue du Progrès/Vooruitgangsstraat 80 – 1035 Brussels M Metro lines and stops Telephone helpline open on 17 and 18 September from 10h00 to 17h00: 02/204.17.69 – Fax: 02/204.15.22 – www.heritagedaysbrussels.be T Trams [email protected] – #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers B Bus reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. g Walking Tour/Activity Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not Exhibition/Conference bring rucksacks or large bags. h “Listed” at the end of notices indicates the date on which the property described Bicycle Tour was listed or registered on the list of protected buildings. b The coordinates indicated in bold beside addresses refer to a map of the Region. Bus Tour A free copy of this map can be requested by writing to the Department of f Monuments and Sites. Guided tour only or Please note that advance bookings are essential for certain tours (reservation i bookings are essential number indicated below the notice). This measure has been implemented for the sole purpose of accommodating the public under the best possible conditions and ensuring that there are sufficient guides available. -

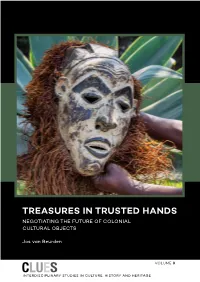

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Studies and Essays Commemorating the 400Th Anniversary of His Birth

EVLİYÂ ÇELEBİ Studies and Essays Commemorating the 400th Anniversary of his Birth EDITORS Nuran Tezcan · Semih Tezcan Robert Dankoff REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM PUBLICATIONS © REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE © THE BANKS ASSOCIATION OF TURKEY AND TOURISM GENERAL DIRECTORATE OF LIBRARIES AND PUBLICATIONS Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism 3358 The Banks Association of Turkey Publications General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 290, Series of Culture:5 Series of Biographies and Memoirs 40 Certificate Number: 17188 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr www.tbb.org.tr e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-975-17-3617-8 ISBN: 978-605-5327-19-4 ORIGINAL TURKISH EDITION First Edition Evliyâ Çelebi, ©Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications, Ankara, 2011. Print Run: 500. Editors Nuran Tezcan, Semih Tezcan ENGLISH EDITION Editor of the English Edition Robert Dankoff PRODUCTION Isbank Culture Publication Address İstiklal Caddesi, Meşelik Sokak No: 2/4, 34433 Beyoğlu-İstanbul Phone 0 (212) 252 39 91 PRINTED BY Golden Medya Matbaacılık ve Ticaret A.Ş. 100. Yıl Mh. Mas-Sit 1. Cad. No: 88 Bağcılar İstanbul (0212) 629 00 24 Certificate Number: 12358 PRINT RUN 2000 copies. PUBLICATION PLACE AND DATE Istanbul, 2012. COVER FIGURE Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi, Hazine 2148 (Album, c. 1720-30) 8a Osmanlı Resim Sanatı (Edited by: Serpil Bağcı, Filiz Çağman, Günsel Renda, Zeren Tanındı; Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Yayınları, İstanbul, 2006) fig. 194. Evliyâ Çelebi Studies and essays commemorating the 400th anniversary of his birth / Editors Nuran Tezcan, Semih Tezcan, Robert Dankoff.- English Edition.- Istanbul: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, The Bank Association of Turkey, 2012. -

Mitchell Short CV

STEPHEN A. MITCHELL Warren House, Barker Center, Harvard University 12 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138 USA. e-mail: [email protected] websites: http://scholar.harvard.edu/smitchell/ https://harvard.academia.edu/StephenMitchell ABBREVIATED CV (OCTOBER 2019) PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT: Robert S. and Ilse Friend Professor of Scandinavian and Folklore, Harvard University. Member, Medieval Studies Committee; Standing Committee on Archaeology; and Committee on Degrees in Folklore and Mythology. Curator of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature. EDUCATION: 1980 Ph.D. in Scandinavian; minor in Germanic Philology, Univ. of Minnesota. 1977 M.A. in Scandinavian; minor in Anthropology, Univ. of Minnesota. 1974 A.B. in Anthropology and Scandinavian, with Highest Honors in Scandinavian, Univ. of California, Berkeley. 1972-73, Student at Lunds universitet (studies at Etnologiska institutionen and Institutionen för nordiska språk; no 1979 degrees taken) SELECTED RECENT AWARDS & HONORS: 2019 Jarl Gallén Prize, Helsinki, “for his important and inspirational research on the mediaeval period in Northern Europe” 2015 Honorary Doctorate (Doctor philosophiae honoris causa), Aarhus University. 2013 Fellow, Swedish Collegium for Advanced Studies, Uppsala University (in progress; Nordic Charm Magic: Word Power and Tradition in Medieval and Early Modern Scandinavia [working title]) 2012 The Ambiguities of Memory Construction in Medieval Texts: The Nordic Case, research seminar, funded by Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University. 2012 Keynote address, 15th International Saga Conference. “Representing the Past in the Sagas: Relique or Blank Slate?” 2011 Walter Channing Cabot Fellowship for distinction in scholarly publication (Witchcraft and Magic in the Nordic Middle Ages). 2009 Visiting Fellow, Aarhus University, Denmark (completed; see Witchcraft and Magic in the Nordic Middle Ages).