11 Selected Syndromes and Associations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tall Stature: a Difficult Diagnosis? Cristina Meazza1* , Chiara Gertosio2, Roberta Giacchero3, Sara Pagani1 and Mauro Bozzola1

Meazza et al. Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2017) 43:66 DOI 10.1186/s13052-017-0385-5 REVIEW Open Access Tall stature: a difficult diagnosis? Cristina Meazza1* , Chiara Gertosio2, Roberta Giacchero3, Sara Pagani1 and Mauro Bozzola1 Abstract Referral for an assessment of tall stature is less common than for short stature. Tall stature is defined as a height more than two standard deviations above the mean for age. The majority of subjects with tall stature show a familial tall stature or a constitutional advance of growth (CAG), which is a diagnosis of exclusion. After a careful physical evaluation, tall subjects may be divided into two groups: tall subjects with normal appearance and tall subjects with abnormal appearance. In the case of normal appearance, the paediatric endocrinologist will have to evaluate the growth rate. If it is normal for age and sex, the subject may be classified as having familial tall stature, CAG or obese subject, while if the growth rate is increased it is essential to evaluate pubertal status and thyroid status. Tall subjects with abnormal appearance and dysmorphisms can be classified into those with proportionate and disproportionate syndromes. A careful physical examination and an evaluation of growth pattern are required before starting further investigations. Physicians should always search for a pathological cause of tall stature, although the majority of children are healthy and they generally do not need treatment to cease growth progression. The most accepted and effective treatment for an excessive height prediction is inducing puberty early and leading to a complete fusion of the epiphyses and achievement of final height, using testosterone in males and oestrogens in females. -

Genetic Investigation of Patients with Tall Stature

2 182 E Vasco de Albuquerque Genetic investigation of tall 182:2 139–147 Clinical Study Albuquerque and others stature patients Genetic investigation of patients with tall stature Edoarda Vasco de Albuquerque Albuquerque1, Mariana Ferreira de Assis Funari2, Elisângela Pereira de Souza Quedas1, Rachel Sayuri Honjo Kawahira3, Raquel Soares Jallad4, Thaís Kataoka Homma1, Regina Matsunaga Martin2,5, Vinicius Nahime Brito2, Alexsandra Christianne Malaquias1,6, Antonio Marcondes Lerario1,7, Carla Rosenberg8, Ana Cristina Victorino Krepischi8, Chong Ae Kim3, Ivo Jorge Prado Arnhold2 and Alexander Augusto de Lima Jorge1 1Unidade de Endocrinologia Genética (LIM25), 2Unidade de Endocrinologia do Desenvolvimento, Laboratório de Hormônios e Genética Molecular (LIM42), Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, Brasil, 3Unidade de Genética do Instituto da Criança, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 4Unidade de Neuroendocrinologia, 5Unidade de Doenças Osteometabólicas, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, Brasil, 6Unidade de Endocrinologia Pediátrica, Correspondence Departamento de Pediatria, Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 7Division of should be addressed Metabolism, Endocrinology and Diabetes, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, to A A L Jorge Michigan, USA, and 8Instituto de Biociências (IB), Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, Brasil Email [email protected] Abstract Context: Patients with tall stature often remain undiagnosed after clinical investigation and few studies have genetically assessed this group, most of them without a systematic approach. Objective: To assess prospectively a group of individuals with tall stature, with and without syndromic features, and to establish a molecular diagnosis for their growth disorder. -

New Microdeletion and Microduplication Syndromes: a Comprehensive Review

Genetics and Molecular Biology, 37, 1 (suppl), 210-219 (2014) Copyright © 2014, Sociedade Brasileira de Genética. Printed in Brazil www.sbg.org.br Review Article New microdeletion and microduplication syndromes: A comprehensive review Julián Nevado1,2*, Rafaella Mergener3*, María Palomares-Bralo1,2, Karen Regina Souza3, Elena Vallespín1,2, Rocío Mena1,2, Víctor Martínez-Glez1,2, María Ángeles Mori1,2, Fernando Santos1,4, Sixto García-Miñaur1,4, Fé García-Santiago1,5, Elena Mansilla1,5, Luis Fernández1,6, María Luisa de Torres1,5, Mariluce Riegel3,7$ and Pablo Lapunzina1,4,8$ 1Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Raras, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. 2Section of Functional and Structural Genomics, Instituto de Genética Médica y Molecular, Hospital Universitario la Paz, Madrid, Spain. 3Programa de Pós-graduação em Genética e Biologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre,RS, Brazil. 4Section of Clinical Genetics, Instituto de Genética Médica y Molecular, Hospital Universitario la Paz, Madrid, Spain. 5Section of Cytogenetics, Instituto de Genética Médica y Molecular, Hospital Universitario la Paz, Madrid, Spain. 6Section of Preanalytics, Instituto de Genética Médica y Molecular, Hospital Universitario la Paz, Madrid, Spain. 7Serviço de Genética Médica, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre ,RS, Brazil. 8Section of Molecular Endocrinology, Overgrowth Disordes Laboratory, Instituto de Genética Médica y Molecular, Hospital Universitario la Paz, Madrid, Spain. Abstract Several new microdeletion and microduplication syndromes are emerging as disorders that have been proven to cause multisystem pathologies frequently associated with intellectual disability (ID), multiple congenital anomalies (MCA), autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) and other phenotypic findings. In this paper, we review the “new” and emergent microdeletion and microduplication syndromes that have been described and recognized in recent years with the aim of summarizing their main characteristics and chromosomal regions involved. -

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

Level Estimates of Maternal Smoking and Nicotine Replacement Therapy During Pregnancy

Using primary care data to assess population- level estimates of maternal smoking and nicotine replacement therapy during pregnancy Nafeesa Nooruddin Dhalwani BSc MSc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 ABSTRACT Background: Smoking in pregnancy is the most significant preventable cause of poor health outcomes for women and their babies and, therefore, is a major public health concern. In the UK there is a wide range of interventions and support for pregnant women who want to quit. One of these is nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) which has been widely available for retail purchase and prescribing to pregnant women since 2005. However, measures of NRT prescribing in pregnant women are scarce. These measures are vital to assess its usefulness in smoking cessation during pregnancy at a population level. Furthermore, evidence of NRT safety in pregnancy for the mother and child’s health so far is nebulous, with existing studies being small or using retrospectively reported exposures. Aims and Objectives: The main aim of this work was to assess population- level estimates of maternal smoking and NRT prescribing in pregnancy and the safety of NRT for both the mother and the child in the UK. Currently, the only population-level data on UK maternal smoking are from repeated cross-sectional surveys or routinely collected maternity data during pregnancy or at delivery. These obtain information at one point in time, and there are no population-level data on NRT use available. As a novel approach, therefore, this thesis used the routinely collected primary care data that are currently available for approximately 6% of the UK population and provide longitudinal/prospectively recorded information throughout pregnancy. -

Macrocephaly Information Sheet 6-13-19

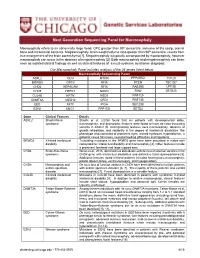

Next Generation Sequencing Panel for Macrocephaly Clinical Features: Macrocephaly refers to an abnormally large head, OFC greater than 98th percentile, inclusive of the scalp, cranial bone and intracranial contents. Megalencephaly, brain weight/volume ratio greater than 98th percentile, results from true enlargement of the brain parenchyma [1]. Megalencephaly is typically accompanied by macrocephaly, however macrocephaly can occur in the absence of megalencephaly [2]. Both macrocephaly and megalencephaly can been seen as isolated clinical findings as well as clinical features of a mutli-systemic syndromic diagnosis. Our Macrocephaly Panel includes analysis of the 36 genes listed below. Macrocephaly Sequencing Panel ASXL2 GLI3 MTOR PPP2R5D TCF20 BRWD3 GPC3 NFIA PTEN TBC1D7 CHD4 HEPACAM NFIX RAB39B UPF3B CHD8 HERC1 NONO RIN2 ZBTB20 CUL4B KPTN NSD1 RNF125 DNMT3A MED12 OFD1 RNF135 EED MITF PIGA SEC23B EZH2 MLC1 PPP1CB SETD2 Gene Clinical Features Details ASXL2 Shashi-Pena Shashi et al. (2016) found that six patients with developmental delay, syndrome macrocephaly, and dysmorphic features were found to have de novo truncating variants in ASXL2 [3]. Distinguishing features were macrocephaly, absence of growth retardation, and variability in the degree of intellectual disabilities The phenotype also consisted of prominent eyes, arched eyebrows, hypertelorism, a glabellar nevus flammeus, neonatal feeding difficulties and hypotonia. BRWD3 X-linked intellectual Truncating mutations in the BRWD3 gene have been described in males with disability nonsyndromic intellectual disability and macrocephaly [4]. Other features include a prominent forehead and large cupped ears. CHD4 Sifrim-Hitz-Weiss Weiss et al., 2016, identified five individuals with de novo missense variants in the syndrome CHD4 gene with intellectual disabilities and distinctive facial dysmorphisms [5]. -

Prenatal Diagnosis of Frequently Seen Fetal Syndromes (AZ)

Prenatal diagnosis of frequently seen fetal syndromes (A-Z) Ibrahim Bildirici,MD Professor of OBGYN ACIBADEM University SOM Attending Perinatologist ACIBADEM MASLAK Hospital Amniotic band sequence: Amniotic band sequence refers to a highly variable spectrum of congenital anomalies that occur in association with amniotic bands The estimated incidence of ABS ranges from 1:1200 to 1:15,000 in live births, and 1:70 in stillbirths Anomalies include: Craniofacial abnormalities — eg, encephalocele, exencephaly, clefts, which are often in unusual locations; anencephaly. Body wall defects (especially if not in the midline), abdominal or thoracic contents may herniate through a body wall defect and into the amniotic cavity. Limb defects — constriction rings, amputation, syndactyly, clubfoot, hand deformities, lymphedema distal to a constriction ring. Visceral defects — eg, lung hypoplasia. Other — Autotransplanted tissue on skin tags, spinal defects, scoliosis, ambiguous genitalia, short umbilical cord due to restricted motion of the fetus Arthrogryposis •Multiple congenital joint contractures/ankyloses involving two or more body areas •Pena Shokeir phenotype micrognathia, multiple contractures, camptodactyly (persistent finger flexion), polyhydramnios *many are AR *Lethal due to pulmonary hypoplasia • Distal arthrogryposis Subset of non-progressive contractures w/o associated primary neurologic or muscle disease Beckwith Wiedemannn Syndrome Macrosomia Hemihyperplasia Macroglossia Ventral wall defects Predisposition to embryonal tumors Neonatal hypoglycemia Variable developmental delay 85% sporadic with normal karyotype 10-15% autosomal dominant inheritance 10-20% with paternal uniparental disomy (Both copies of 11p15 derived from father) ***Imprinting related disorder 1/13 000. Binder Phenotype a flat profile and depressed nasal bridge. Short nose, short columella, flat naso-labial angle and perialar flattening Isolated Binder Phenotype transmission would be autosomal dominant Binder Phenotype can also be an important sign of chondrodysplasia punctata (CDDP) 1. -

Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases Collection

Marche des Maladies Rares – Alliance Maladies Rares Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases collection DecemberOctober 2013 2009 List of rare diseases and synonyms Listed in alphabetical order www.orpha.net 20102206 Rare diseases listed in alphabetical order ORPHA ORPHA ORPHA Disease name Disease name Disease name Number Number Number 289157 1-alpha-hydroxylase deficiency 309127 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase 228384 5q14.3 microdeletion syndrome deficiency 293948 1p21.3 microdeletion syndrome 314655 5q31.3 microdeletion syndrome 939 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria 1606 1p36 deletion syndrome 228415 5q35 microduplication syndrome 2616 3M syndrome 250989 1q21.1 microdeletion syndrome 96125 6p subtelomeric deletion syndrome 2616 3-M syndrome 250994 1q21.1 microduplication syndrome 251046 6p22 microdeletion syndrome 293843 3MC syndrome 250999 1q41q42 microdeletion syndrome 96125 6p25 microdeletion syndrome 6 3-methylcrotonylglycinuria 250999 1q41-q42 microdeletion syndrome 99135 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase 67046 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 1 deficiency 238769 1q44 microdeletion syndrome 111 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 2 13 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase 976 2,8 dihydroxyadenine urolithiasis deficiency 67047 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 3 869 2A syndrome 75857 6q terminal deletion 67048 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 4 79154 2-aminoadipic 2-oxoadipic aciduria 171829 6q16 deletion syndrome 66634 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 5 19 2-hydroxyglutaric acidemia 251056 6q25 microdeletion syndrome 352328 3-methylglutaconic -

Sotos Syndrome

European Journal of Human Genetics (2007) 15, 264–271 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1018-4813/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/ejhg PRACTICAL GENETICS In association with Sotos syndrome Sotos syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition characterised by a distinctive facial appearance, learning disability and overgrowth resulting in tall stature and macrocephaly. In 2002, Sotos syndrome was shown to be caused by mutations and deletions of NSD1, which encodes a histone methyltransferase implicated in chromatin regulation. More recently, the NSD1 mutational spectrum has been defined, the phenotype of Sotos syndrome clarified and diagnostic and management guidelines developed. Introduction In brief Sotos syndrome was first described in 1964 by Juan Sotos Sotos syndrome is characterised by a distinctive facial and the major diagnostic criteria of a distinctive facial appearance, learning disability and childhood over- appearance, childhood overgrowth and learning disability growth. were established in 1994 by Cole and Hughes.1,2 In 2002, Sotos syndrome is associated with cardiac anomalies, cloning of the breakpoints of a de novo t(5;8)(q35;q24.1) renal anomalies, seizures and/or scoliosis in B25% of translocation in a child with Sotos syndrome led to the cases and a broad variety of additional features occur discovery that Sotos syndrome is caused by haploinsuffi- less frequently. ciency of the Nuclear receptor Set Domain containing NSD1 abnormalities, such as truncating mutations, protein 1 gene, NSD1.3 Subsequently, extensive analyses of missense mutations in functional domains, partial overgrowth cases have shown that intragenic NSD1 muta- gene deletions and 5q35 microdeletions encompass- tions and 5q35 microdeletions encompassing NSD1 cause ing NSD1, are identifiable in the majority (490%) of 490% of Sotos syndrome cases.4–10 In addition, NSD1 Sotos syndrome cases. -

MED12 Mutations Link Intellectual Disability Syndromes with Dysregulated GLI3-Dependent Sonic Hedgehog Signaling

MED12 mutations link intellectual disability syndromes with dysregulated GLI3-dependent Sonic Hedgehog signaling Haiying Zhoua, Jason M. Spaethb, Nam Hee Kimb, Xuan Xub, Michael J. Friezc, Charles E. Schwartzc, and Thomas G. Boyerb,1 aDepartment of Molecular and Cell Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94270; bDepartment of Molecular Medicine, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229; and cGreenwood Genetic Center, Greenwood, SC 29646 Edited by Robert G. Roeder, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, and approved September 13, 2012 (received for review December 20, 2011) Recurrent missense mutations in the RNA polymerase II Mediator divergent “tail” and “kinase” modules through which most activa- subunit MED12 are associated with X-linked intellectual disability tors and repressors target Mediator. The kinase module, compris- (XLID) and multiple congenital anomalies, including craniofacial, ing MED12, MED13, CDK8, and cyclin C, has been ascribed both musculoskeletal, and behavioral defects in humans with FG (or activating and repressing functions and exists in variable association Opitz-Kaveggia) and Lujan syndromes. However, the molecular with Mediator, implying that its regulatory role is restricted to a mechanism(s) underlying these phenotypes is poorly understood. subset of RNA polymerase II transcribed genes. Here we report that MED12 mutations R961W and N1007S causing Within the Mediator kinase module, MED12 is a critical trans- FG and Lujan syndromes, respectively, disrupt a Mediator-imposed ducer of regulatory information conveyed by signal-activated transcription factors linked to diverse developmental pathways, constraint on GLI3-dependent Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling. We including the EGF, Notch, Wnt, and Hedgehog pathways (10–12). -

Soonerstart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions

SoonerStart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions - Appendix O Abetalipoproteinemia Acanthocytosis (see Abetalipoproteinemia) Accutane, Fetal Effects of (see Fetal Retinoid Syndrome) Acidemia, 2-Oxoglutaric Acidemia, Glutaric I Acidemia, Isovaleric Acidemia, Methylmalonic Acidemia, Propionic Aciduria, 3-Methylglutaconic Type II Aciduria, Argininosuccinic Acoustic-Cervico-Oculo Syndrome (see Cervico-Oculo-Acoustic Syndrome) Acrocephalopolysyndactyly Type II Acrocephalosyndactyly Type I Acrodysostosis Acrofacial Dysostosis, Nager Type Adams-Oliver Syndrome (see Limb and Scalp Defects, Adams-Oliver Type) Adrenoleukodystrophy, Neonatal (see Cerebro-Hepato-Renal Syndrome) Aglossia Congenita (see Hypoglossia-Hypodactylia) Aicardi Syndrome AIDS Infection (see Fetal Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) Alaninuria (see Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Deficiency) Albers-Schonberg Disease (see Osteopetrosis, Malignant Recessive) Albinism, Ocular (includes Autosomal Recessive Type) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Brown Type (Type IV) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Negative (Type IA) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Positive (Type II) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Yellow Mutant (Type IB) Albinism-Black Locks-Deafness Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy (see Parathyroid Hormone Resistance) Alexander Disease Alopecia - Mental Retardation Alpers Disease Alpha 1,4 - Glucosidase Deficiency (see Glycogenosis, Type IIA) Alpha-L-Fucosidase Deficiency (see Fucosidosis) Alport Syndrome (see Nephritis-Deafness, Hereditary Type) Amaurosis (see Blindness) Amaurosis -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0210567 A1 Bevec (43) Pub

US 2010O2.10567A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0210567 A1 Bevec (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 19, 2010 (54) USE OF ATUFTSINASATHERAPEUTIC Publication Classification AGENT (51) Int. Cl. A638/07 (2006.01) (76) Inventor: Dorian Bevec, Germering (DE) C07K 5/103 (2006.01) A6IP35/00 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6IPL/I6 (2006.01) WINSTEAD PC A6IP3L/20 (2006.01) i. 2O1 US (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................... 514/18: 530/330 9 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 12/677,311 The present invention is directed to the use of the peptide compound Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH as a therapeutic agent for (22) PCT Filed: Sep. 9, 2008 the prophylaxis and/or treatment of cancer, autoimmune dis eases, fibrotic diseases, inflammatory diseases, neurodegen (86). PCT No.: PCT/EP2008/007470 erative diseases, infectious diseases, lung diseases, heart and vascular diseases and metabolic diseases. Moreover the S371 (c)(1), present invention relates to pharmaceutical compositions (2), (4) Date: Mar. 10, 2010 preferably inform of a lyophilisate or liquid buffersolution or artificial mother milk formulation or mother milk substitute (30) Foreign Application Priority Data containing the peptide Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH optionally together with at least one pharmaceutically acceptable car Sep. 11, 2007 (EP) .................................. O7017754.8 rier, cryoprotectant, lyoprotectant, excipient and/or diluent. US 2010/0210567 A1 Aug. 19, 2010 USE OF ATUFTSNASATHERAPEUTIC ment of Hepatitis BVirus infection, diseases caused by Hepa AGENT titis B Virus infection, acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, full minant liver failure, liver cirrhosis, cancer associated with Hepatitis B Virus infection. 0001. The present invention is directed to the use of the Cancer, Tumors, Proliferative Diseases, Malignancies and peptide compound Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH (Tuftsin) as a thera their Metastases peutic agent for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of cancer, 0008.