Bulls Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

The 1999 Bulls Weren't Gonna Go 50-0 Kelly Dwyer Sep 13, 2019 2

Help Really, what would have gotten in Chicago’s way? The Second Arrangement SubscribeSign in The 1999 Bulls weren't gonna go 50-0 Kelly Dwyer Sep 13, 2019 2 Scottie Pippen & Dennis Rodman: Our Bulls would have gone 50-0 during the l… THE CAP The NBA introduced its new Collective Bargaining Agreement in the rst month of 1999, aer locking its players out for over six months. The Larry Bird rules remained in the new CBA, teams could and can still go over the salary cap to re-sign (most of) their own free agents, but the rest of its writing detailed little outside of constraints. Maximum salaries were introduced, mid-level exceptions were created in order to develop a Recently, while joking, Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman agreed that the 1999 Chicago Bulls semblance of “NBA middle class,” and the salary cap was raised by $3.1 million to $30 million could have gone 50-0 had the franchise returned 1998’s championship core. for the 1999 season. This reunion included not only free agents Pippen and Rodman but also Michael Jordan and Michael Jordan alone ($33.1 million) made more than this number the season before, he and Phil Jackson, with Jackson’s clinching far less certain than the rest. Splayed out over an NBA the rest of the outsized money-makers (Kevin Garnett, Alonzo Mourning, Shaquille O’Neal, season shortened to 50 games due to the NBA’s owner lockout, Pippen and Rodman appear to presumably Patrick Ewing) were allowed a grandfather clause and the ability to make a believe the club’s spirit and cohesion would have blended well over the course of a cut-rate percentage on top of whatever largess each entered the post-lockout world with. -

Matt's Musings Block Party

Matt’s Musings Block Party Thankfully, Chris hasn’t figured out that he’s far too smart and informed to be wasting did the day he died, untouched and unoccupied. Apparently a homage to Arthur, Bill his name on us, so we’re glad to have him here again. Wirtz would have never approved of such a thing. Being now the first Wirtz family member to be resoundingly celebrated is In the November issue of Chicago Magazine, there was an article done by fitting Rocky just fine. Whether it’s putting himself front and center prior to puck drop Andreas Larsson on Rocky Wirtz and the Wirtz family that is worth going out of your for the home opener, glad-handing on the United Center concourse or watching just way to find. While containing some interesting facts and insight into the business of about every game from his usual perch in section 119, he’s embracing his newfound the Blackhawks this is more of a story about Rocky, his late-father Bill and Grandfa- notoriety with a frisky wide-smile that sometimes borders on giddiness. ther Arthur, and the association amongst those men than it is a chronicle of a hockey As mentioned in the article, it was his brother Peter who insisted the team organization. honor their father before last season’s home opening game with Detroit. The entire It’s been 17 months now since Rocky Wirtz, on his 55th birthday, an- Wirtz family stood in the 100-level center ice suite mortified as a large percentage nounced he would be taking over the Blackhawks and occupy the Chairman’s position of the 18,000 fans in attendance booed and shouted obscenities during a ceremony that had been vacated since Arthur M. -

Calling Sports Sociology Off the Bench

Calling Sports Sociology Off the Bench Dave Zirin Sports writer Published on the Internet, www.idrottsforum.org/articles/zirin/zirin081126.html (ISSN 1652–7224), 2008–11–26 Copyright © Dave Zirin 2008. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. Broadly speaking, the texts published on idrottsforum.org discusses the changes in sports in our time; indeed, the most important task of the social sciences is to map and understand contemporary changes based on knowledge of the past and theories of change and devel- opment. We draw attention, often in sweeping terms, to the general tendencies of change within modern sports – commercialization, professionalization, globalization, medializa- tion. These tendencies are indisputable and unchallenged, even if opinions differ as to their advantages and disadvantages for the actual performance and intrinsic values of sports. What do these tendencies entail? What are the everyday consequences? These kinds of questions are also dealt with on the forum – our original articles as well as the large num- ber of reviews of works published elsewhere indicate the changes as they appear in the everyday sporting reality. But to what extent is sports journalism contributing to a balanced assessment of the changes within sports? And what part can sports sociology play in this? Crisis! That’s Dave Zirin’s diagnosis of the situation within, primarily, American sports and American sports journalism. -

August 10, 2015 MIAA Endowment Celebrity Golf Tournament

MIAA Endowment Celebrity Golf Tournament Plymouth Country Club Plymouth, MA August 10, 2015 MIAA Endowment Celebrity Golf Tournament Welcome! The MIAA Endowment Fund was established in 2013. The goal of this fund is to preserve and create educational opportunities for student-athletes statewide. The Endowment fund helps the MIAA maintain quality services under the umbrella of the five education based athletic “Pillars”: Coaches Education, Com- munity Service, Leadership, Sportsmanship and Wellness. Through your participation, donation or sponsorship to this event the MIAA is able to raise funds that will aid in supporting full participation by student-athletes in programs sponsored by the MIAA. Programs such as: New England Student Leadership Conference, Girls and Women in Sport Day, Sportsmanship Summit, The Camp Edwards Captains Challenge, Citizenship Day, Wellness Summit, as well as, various leadership and wellness workshops throughout the year. We are excited to have our tournament at the Plymouth Country Club. It is our hope that you have the best day of golf ever. Relax, have fun and enjoy! Today’s Schedule 11:00 am Registration 12:00 pm Shotgun Scramble Start 4:30 pm Relax in Lounge Reception Silent Auction Bidding 5:30 pm Dinner Winner Announcements Awards/Prizes Thank You Thank You 137 Samoset Street, Plymouth MA Proud Sponsor: Hole-In-One Prize 2015 Silverado Pick Up Plymouth Country Club August 10, 2015 Format for Golf: SCRAMBLE Each player will drive. The team will then select the best location from which to play and the entire team will play from that position. Continue this process until the ball is holed. -

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

Capital Punishment in Illinois in the Aftermath of the Ryan Commutations

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 2010 CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN ILLINOIS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE RYAN COMMUTATIONS: REFORMS, ECONOMIC REALITIES, AND A NEW SALIENCY FOR ISSUES OF COST Leigh Buchanan Bienen Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation Bienen, Leigh Buchanan, "CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN ILLINOIS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE RYAN COMMUTATIONS: REFORMS, ECONOMIC REALITIES, AND A NEW SALIENCY FOR ISSUES OF COST" (2010). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 118. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/10/10004-0001 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 100, No. 4 Copyright © 2010 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN ILLINOIS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE RYAN COMMUTATIONS: REFORMS, ECONOMIC REALITIES, AND A NEW SALIENCY FOR ISSUES OF COST LEIGH B. BIENEN Perhaps most telling is the view of Professor Joseph Hoffman, someone who has devoted enormous time and energy to death penalty reform, spearheading death penalty reform efforts in both Illinois and Indiana and serving as Co-Chair and Reporter for the Massachusetts Governor‘s Council on Capital Punishment. Hoffman served as a member of an advisory group to discuss an earlier draft of this paper, and he strongly expressed the view that seeking reform of capital punishment in the political realm is futile. -

Rea< '86 W< a S 'Gc 3Ody< Ear' I

M MellowJ kids at COollege—B16 Cham^berbgch^ s B u r / e y- B i p P .’.[ i l l m n p i $ 1 . 0 0 81!ilstyear, No.362 T w in F a lls, Id,Id a h o Sunday, Dec)Bcember28,198I&: : .......... Rea< ’86 w<a s ‘gc3ody<ear’ I %ays his h lings to free American By The Associated Press■ess I ! The presidenl praisedI VW allenberg covert dealln; for pointing out "that viwhile dally hostages In Iran,Ir R eagan said "1988 . ;i in,controv LOS ANGELES -— President news reports in recent years> bave has been a goodgoo y e a r for tbe cause of p* a U p Reagan, on a New YeYear’s vacation focus^ on negative eievents and human freedcedom and good for the p u u > , • far (rom WaEhlngtoo0 iand the Iran- predictions of gloom andid doom, o u r cause of worldrldpeace.” . 'i Contra controversy, all but ignored country and our people acliclually b av e ‘The prealdeident also said his sumiflil tils biggest problem, SiSaturday, say- been moving forward,1, problem s nieellng wllhth Soviet leader Mikhail ^ ing 1906 "w as a very googood year." ' solved, opportunity openlniIng » Gorbachevat at Reykjavik, Iceland, in 7^i^tiai^^iaSSSSi9J«r nnl>y. m itW g a;'! In bis weekly racradio address, jwed differences between The year 1986, Reaganntbldhlsau- i recorded in advance to be broadcast iperpowers over nuclear ^ dlence, *‘wlU be remembe while he was flying to iCallfomla tor lions "had narrowed con- ■: for some Important and 1 n n m a holiday, week tn LosjOS Angeles aod • evenly that the politic Palm Sprlngs, Reagatgan made only ; lo a soiig made popular' i)! doh’f rem em ber or mayay nol have , brief mention of the: cicHsis that'hu d, Frank Sinalra, Reagan fi noticed." enveloped his presidenc;incy. -

Procurement Services

FOIA Request Log - Procurement Services REQUESTOR NAME ORGANIZATION Allan R. Popper Linguard, Inc. Maggie Kenney n/a Leigh Marcotte n/a Jeremy Lewno Bobby's Bike Hike Diane Carbonara Fox News Chicago Chad Dobrei Tetra Tech EM, Inc James Brown AMCAD Laura Waxweiler n/a Robert Jones Contractors Adjustment Company Robert Jones Contractors Adjustment Company Allison Benway Chico & Nunes, P.C. Rey Rivera Humboldt Construction Bennett Grossman Product Productions/Space Stage Studios Robert Jones Contractors Adjustment Company Larry Berman n/a Arletha J. Newson Arletha's Aua Massage Monica Herrera Chicago United Industries James Ziegler Stone Pogrund & Korey LLC Bhav Tibrewal n/a Rey Rivera CSI 3000 Inc. Page 1 of 843 10/03/2021 FOIA Request Log - Procurement Services DESCRIPTION OF REQUEST Copy of payment bond for labor & material for the Chicago Riverwalk, South side of Chicago River between State & Michigan Ave. How to find the Department of Procurement's website A copy of disclosure 21473-D1 Lease agreement between Bike Chicago & McDonald's Cycle center (Millennium Park Bike Station) All copies of contracts between Xora and the City of Chicago from 2000 to present. List of City Depts. that utilized the vendor during time frame. The technical and cost proposals & the proposal evaluation documents for the proposal submitted by Beck Disaster Recovery. the proposal evaluation documents for the proposal submitted by Tetra Tech EM, Inc and the contract award justification document Copies of the IBM/Filenet and Crowe proposals for Spec 68631 Copies -

Today's News Clips June 7, 2018

Today’s News Clips June 7, 2018 Chicago Sun-Times Patrick Kane, 6 other Blackhawks set to play in Chicago summer hockey league Satchel Price June 6, 2018 Several Blackhawks players will be taking part in a new summer hockey league coming to Chicago in July. The Chicago Pro Hockey League announced its inaugural eight-game exhibition season Wednesday with planned participants including Patrick Kane, Alex DeBrincat, Nick Schmaltz and many others. Over 80 players from the NHL, AHL and ECHL are expected to be play in the games at MB Ice Arena, the new practice facility that the Hawks opened in January, as well as a large number of top amateurs from top college programs, junior teams and AAA programs. Kane and DeBrincat are set to play on the same team, continuing their partnership from Team USA’s run at the 2018 World Championships. Brandon Saad, Tommy Wingels and Ryan Hartman will also be teammates again, along with former Hawks forward Brandon Bollig. “The CPHL is a great opportunity for our Chicago-based players to participate in high-level games to supplement their summer training programs,” said Blackhawks GM Stan Bowman as part of the announcement. “I’m thrilled to see so many Chicago Blackhawks’ players involved, and also thrilled that our local hockey fans will be able to visit our new practice facility and see some great summer hockey.” The first game of the weekly CPHL season will be July 11 and tickets will be a delightfully cheap $5 each. There will also be games on July 18, July 25, Aug. -

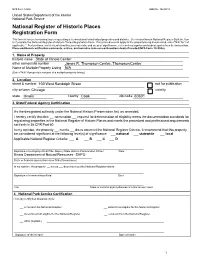

Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" If Property Is Not Part of a Multiple Property Listing)

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name State of Illinois Center other names/site number James R. Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 100 West Randolph Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Department of Natural Resources - SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

BINGO Ieuming Irralh

PAGE TWENTY-FOUR iH a n rh P lpr €imttng FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 1969 0 Avenge Dnfly Net Press Ron IW Tte Week Haded Football Women Voter Canva.ss to Mr. and Mrs. James Porter, The W e a th e r About Town Manchester Amston; a son to Mr. and Mrs. Lights Asked dW e 28. U*» /The R ev. James Birdsall, Set Social Event The Manchester registrars William Houle, 65 Bette Circle, Cloudiness increasing thi. af. vicar of St. Peter’s Ki>iscopaI of voters have mailed no Hospital Note.s Vernon; a daughter-to Mr. and temoon and tonight with chance Church in. Wapplng, will con Women’s Axixlllary of Man tices to approxim ately 1,400 M rs. Donald H ahn, 127 School For Street 15,459 of showers. Tonight’s low 60 to iEuming Irralh 56. ’Tomorrow partly cloudgr, duct a service Sunday at 8:15 chester iMldget and Pony Foot-, persons on the voting lists, V IS m N a HOCB8 St.: a son to Mr. and Mrs. Ger a.m. on radio station WINF. Inteniiedlate Care Semi- A request for street Ugtits on MmneheMter— A City of ViUate Charm cod wkh highs 66 to TO. ball Association will hold a get- none of whom were at their ald Nicholson, East Hartford. 'Kie program is sponsored by voting addresses of record private, noon-Z p.m ., and 4 p.m. DISCHARGED YESTERDAY: Elizabeth Dr., a repeat com VOL. LXXXVm, NO. 299 the Manchester Council of acquainted session for mothers 8 p.m.; private rooms, 10 a.m.- Jo h n E .