Ensemble 415

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Academy Fee the Academy Fee Is 540 € for Each Participant

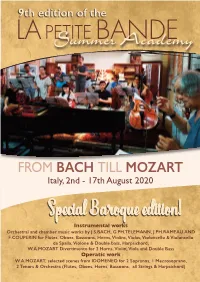

9th edition of the LA PESTuITmE mBerA ANcaDdEemy FROM BACH TILL MOZART Italy, 2nd - 17th August 2020 SpeciIanstlr uBmenatarl woorqks ue edition! Orchestral and chamber music works by J.S.BACH, G.PH.TELEMANN, J.PH.RAMEAU AND F.COUPERIN for Flutes, Oboes, Bassoons, Horns, Violins, Violas, Violoncello & Violoncello da Spalla, Violone & Double bass, Harpsichord; W.A.MOZART Divertimento for 2 Horns, Violin, Viola and Double Bass Operatic work W.A.MOZART, selected scenes from IDOMENEO for 2 Sopranos, 1 Mezzosoprano, 2 Tenors & Orchestra (Flutes, Oboes, Horns, Bassoons, all Strings & Harpsichord) LA PESTuITmE mBerA ANcaDdEemy Since 2012, La Petite BandeA orgpanpizleis caa yetairolyn Susm mforer A c2ad0em2y 0in Itaalyr, ew hnicho wwith othpe eyenar! s has become a beloved international appointment for many musicians desiring to deepen their knowledge and practice of historically informed practice for the baroque and classical repertoire (especially Mozart & Haydn). Indeed, they have taken their chance to work with one of the pioneers of this field, violinist and leader of La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken. Each year, the Academy focuses both on instrumental and operatic works. Singers work with Marie Kuijken on a historically informed approach to the textual and scenical aspects of the score, and perform the opera with the orchestra. The 2020 edition is a special BAROQUE edition, in which the instrumental focus will be on orchestral and chamber music works of J.S.Bach, G.Telemann, J.Ph.Rameau aBnda F.rCooupqeruine. By choosing mostly to play one-to-a-part, for these works the difference between orchestral and chambermusic playing will be minimal. -

08 November 2020

08 November 2020 12:01 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Don Giovanni overture Romanian Radio National Orchestra, Tiberiu Soare (conductor) ROROR 12:08 AM Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Hymn to St Cecilia for chorus Op 27 BBC Singers, David Hill (conductor) GBBBC 12:18 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) 8 Variations on Mozart's 'La ci darem la mano' Hyong-Sup Kim (oboe), Ja-Eun Ku (piano) KRKBS 12:28 AM Henricus Albicastro (fl.1700-06) Concerto a 4, Op 7 no 2 Chiara Banchini (violin), Ensemble 415, Chiara Banchini (director) CHRSR 12:37 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Ballade for piano no. 1 (Op.23) in G minor Zbigniew Raubo (piano) PLPR 12:46 AM Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) Pan og Syrinx Op 49 FS.87 Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Michael Schonwandt (conductor) DKDR 12:55 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Trio for clarinet or viola, cello and piano (Op.114) in A minor Ellen Margrethe Flesjo (cello), Hans Christian Braein (clarinet), Havard Gimse (piano) NONRK 01:20 AM Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643) Four Works Enrico Baiano (harpsichord) CHSRF 01:35 AM Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Piano Concerto no 2 in D minor, Op 40 Victor Sangiorgio (piano), West Australian Symphony Orchestra, Vladimir Verbitsky (conductor) AUABC 02:01 AM Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) March: The Song of the Lark, from 'The Seasons, op. 37b' Evgeny Konnov (piano) ESCAT 02:03 AM Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915) Three Etudes for Piano, op. 65 Evgeny Konnov (piano) ESCAT 02:12 AM Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Tango Evgeny Konnov (piano) ESCAT 02:15 AM Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Three Movements from 'Petrushka' Evgeny Konnov (piano) ESCAT 02:33 AM Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943) Prelude in G sharp minor, op. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

Concert Season 34

Concert Season 34 REVISED CALENDAR 2020 2021 Note from the Maestro eAfter an abbreviated Season 33, VoxAmaDeus returns for its 34th year with a renewed dedication to bringing you a diverse array of extraordinary concerts. It is with real pleasure that we look forward, once again, to returning to the stage and regaling our audiences with the fabulous programs that have been prepared for our three VoxAmaDeus performing groups. (Note that all fall concerts will be of shortened duration in light of current guidelines.) In this year of necessary breaks from tradition, our season opener in mid- September will be an intimate Maestro & Guests concert, September Soirée, featuring delightful solo works for piano, violin and oboe, in the spacious and acoustically superb St. Katharine of Siena Church in Wayne. Vox Renaissance Consort will continue with its trio of traditional Renaissance Noël concerts (including return to St. Katharine of Siena Church) that bring you back in time to the glory of Old Europe, with lavish costumes and period instruments, and heavenly music of Italian, English and German masters. Ama Deus Ensemble will perform five fascinating concerts. First is the traditional December Handel Messiah on Baroque instruments, but for this year shortened to 80 minutes and consisting of highlights from all three parts. Then, for our Good Friday concert in April, a program of sublime music, Bach Easter Oratorio & Rossini Stabat Mater; in May, two glorious Beethoven works, the Fifth Symphony and the Missa solemnis; and, lastly, two programs in June: Bach & Vivaldi Festival, as well as our Season 34 Grand Finale Gershwin & More (transplanted from January to June, as a temporary break from tradition), an exhilarating concert featuring favorite works by Gershwin, with the amazing Peter Donohoe as piano soloist, and also including rousing movie themes by Hans Zimmer and John Williams. -

TCB Groove Program

www.piccolotheatre.com 224-420-2223 T-F 10A-5P 37 PLAYS IN 80-90 MINUTES! APRIL 7- MAY 14! SAVE THE DATE! NOVEMBER 10, 11, & 12 APRIL 21 7:30P APRIL 22 5:00P APRIL 23 2:00P NICHOLS CONCERT HALL BENITO JUAREZ ST. CHRYSOSTOM’S Join us for the powerful polyphony of MUSIC INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO COMMUNITY ACADEMY EPISCOPAL CHURCH G.F. Handel's As pants the hart, 1490 CHICAGO AVE PERFORMING ARTS CENTER 1424 N DEARBORN ST. EVANSTON, IL 60201 1450 W CERMAK RD CHICAGO, IL 60610 Domenico Scarlatti's Stabat mater, TICKETS $10-$40 CHICAGO, IL 60608 TICKETS $10-$40 and J.S. Bach's Singet dem Herrn. FREE ADMISSION Dear friends, Last fall, Third Coast Baroque’s debut series ¡Sarabanda! focused on examining the African and Latin American folk music roots of the sarabande. Today, we will be following the paths of the chaconne, passacaglia and other ostinato rhythms – with origins similar to the sarabande – as they spread across Europe during the 17th century. With this program that we are calling Groove!, we present those intoxicating rhythms in the fashion and flavor of the different countries where they gained popularity. The great European composers wrote masterpieces using the rhythms of these ancient dances to create immortal pieces of art, but their weight and significance is such that we tend to forget where their origins lie. Bach, Couperin, and Purcell – to name only a few – wrote music for highly sophisticated institutions. Still, through these dance rhythms, they were searching for something similar to what the more ancient civilizations had been striving to attain: a connection to the spiritual world. -

Bach2000.Pdf

Teldec | Bach 2000 | home http://www.warnerclassics.com/teldec/bach2000/home.html 1 of 1 2000.01.02. 10:59 Teldec | Bach 2000 | An Introduction http://www.warnerclassics.com/teldec/bach2000/introd.html A Note on the Edition TELDEC will be the first record company to release the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach in a uniformly packaged edition 153 CDs. BACH 2000 will be launched at the Salzburg Festival on 28 July 1999 and be available from the very beginning of celebrations to mark the 250th anniversary of the composer's death in 1750. The title BACH 2000 is a protected trademark. The artists taking part in BACH 2000 include: Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Gustav Leonhardt, Concentus musicus Wien, Ton Koopman, Il Giardino Armonico, Andreas Staier, Michele Barchi, Luca Pianca, Werner Ehrhardt, Bob van Asperen, Arnold Schoenberg Chor, Rundfunkchor Berlin, Tragicomedia, Thomas Zehetmair, Glen Wilson, Christoph Prégardien, Klaus Mertens, Barbara Bonney, Thomas Hampson, Herbert Tachezi, Frans Brüggen and many others ... BACH 2000 - A Summary Teldec's BACH 2000 Edition, 153 CDs in 12 volumes comprising Bach's complete works performed by world renowned Bach interpreters on period instruments, constitutes one of the most ambitious projects in recording history. BACH 2000 represents the culmination of a process that began four decades ago in 1958 with the creation of the DAS ALTE WERK label. After initially triggering an impassioned controversy, Nikolaus Harnoncourt's belief that "Early music is a foreign language which must be learned by musicians and listeners alike" has found widespread acceptance. He and his colleagues searched for original instruments to throw new light on composers and their works and significantly influenced the history of music interpretation in the second half of this century. -

Livret-Num-302:Mise En Page 1

J.S. BACH SONATES POUR CLAVECIN OBLIGÉ ET VIOLON BWV 1014 - 1019 CHIARA BANCHINI VIOLON JÖRG-ANDREAS BÖTTICHER CLAVECIN TERRITOIRES ZIG-ZAG JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750 SONATES POUR CLAVECIN OBLIGÉ ET VIOLON DISQUE 2 : BWV 1014 – 1019 DISQUE 1 : SONATE N°4 EN DO MINEUR, BWV 1017 : 1 I. LARGO 2 II. ALLEGRO SONATE N°1 EN SI MINEUR, BWV 1014 : 3 III. ADAGIO 1 I. ADAGIO 4 IV. ALLEGRO 2 II. ALLEGRO 3 III. ANDANTE SONATE N°5 EN FA MINEUR, BWV 1018 : 4 IV. ALLEGRO 5 I. LARGO 6 II. ALLEGRO SONATE N°2 EN LA MAJEUR, BWV 1015 : 7 III. ADAGIO 5 I. DOLCE 8 IV. VIVACE 6 II. ALLEGRO 7 III. ANDANTE UN POCO SONATE N°6 EN SOL MAJEUR, BWV 1019 : 8 IV. PRESTO 9 I. ALLEGRO 10 II. LARGO SONATE N°3 EN MI MAJEUR, BWV 1016 : 11 III. ALLEGRO 9 I. ADAGIO 12 IV. ADAGIO 10 II. ALLEGRO 13 V. ALLEGRO 11 III. ADAGIO MA NON TANTO 12 IV. ALLEGRO 14 - CANTABILE BWV 1019A CHIARA BANCHINI VIOLON JÖRG-ANDREAS BÖTTICHER CLAVECIN ZZT ZZT 302 © Susanna Drescher © Aurel Salzer © Aurel VOIX, STRUCTURES ET UNIVERS EXPRESSIFS DANS LES SONATES DE BACH POUR CLAVIER ET VIOLON ZZT 302 Pour Jean-Sébastien Bach, la composition a toujours représenté, outre les obligations de service et sa fonction d’indispensable gagne-pain, une quête de possibilités et de dimensions nouvelles dissimulées dans le matériau musical. Il a épuisé jusqu’à leurs dernières limites les traditions liées au genre ou à l’interprétation, et les a même souvent poussées au-delà. -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

Nov 23 to 29.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Nov. 23 - Nov. 29, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 11/23/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto for Viola d'amore, lute & orch. 6:15 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 6:29 AM Georg Muffat Sonata No.1 6:42 AM Marianne Martinez Sinfonia 7:02 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for 2 violas 7:09 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Eleven Dances 7:29 AM Henry Purcell Chacony a 4 7:37 AM Robert Schumann Waldszenen 8:02 AM Johann David Heinichen Concerto for 2 flutes, oboes, vn, string 8:15 AM Antonin Reicha Commemoration Symphony 8:36 AM Ernst von Dohnányi Serenade for Strings 9:05 AM Hector Berlioz Harold in Italy 9:46 AM Franz Schubert Moments Musicaux No. 6 9:53 AM Ernesto de Curtis Torna a Surriento 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for horn & orch 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento No. 3 10:21 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata 10:39 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Allegro for Clarinet & String Quartet 10:49 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento No. 8 11:01 AM Aaron Copland Appalachian Spring (Ballet for Martha) 11:29 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Violin Partita No. 2 12:01 PM Bedrich Smetana Ma Vlast: The Moldau ("Vltava") 12:16 PM Astor Piazzolla Tangazo 12:31 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Artist's Life 12:43 PM Luigi Boccherini Flute Quintet No. 3 12:53 PM John Williams (Comp./Cond.) Summon the Heroes 1:01 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Piano Trio No. 1 1:36 PM Margaret Griebling-Haigh Romans des Rois 2:00 PM Johann Sebastian Bach Konzertsatz (Sinfonia) for vln,3 trpts. -

Music by Handel, Purcell, Corelli & Muffat

Belsize Baroque Director: Persephone Gibbs Soprano: Nia Coleman Music by Handel, Purcell, Corelli & Mufat Sunday 27 November 2016, 6.30 pm St Peter’s, Belsize Square, Belsize Park, London NW3 4HY Programme George Friderick Handel (1685–1759) Concerto Grosso in B flat Op.3 No.1 HWV 312 Allegro – Largo – Allegro The Concerti Grossi Opus 3, drawing together pre-existing works by Handel, were published by the less than scrupulous London publisher John Walsh in 1734. A rival composer, Geminiani, had just taken Walsh to court for printing two sets of his Concerti which he claimed Walsh had acquired illegally. While there is no evidence that Handel objected to Walsh’s selection of his works as Opus 3, it looks as if he did not have a chance to edit them pre-publication; it is for instance odd that the last movement of this B flat concerto is in G Minor. The opening movement has solos for the oboes and a violin, the slow movement adds recorders over an orchestral texture with divided violas, and the final movement features bassoons towards the end: all giving London’s best instrumentalists a chance to shine. George Friderick Handel Two arias from the opera Rinaldo, HWV 7 ‘Augelletti, che cantate’ – ‘Lascia ch’io pianga’ Rinaldo is the first Italian opera Handel composed for London, opening in the Haymarket in February 1711. These two arias are sung by Almirena, the daughter of Godfrey of Bouillon, who is capturing the city of Jerusalem from the infidel during the First Crusade (1096–99). Almirena, a character unknown to Torquato Tasso, from whose epic the plot of the opera is drawn, has been introduced into the plot by the librettist to provide a love interest.