French Department Course Handbook 2016-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection 16 French Culture in the Early Modern Period

HISTORY Collection 16 French Culture in the Early Modern Period Early European Books Collection 16 presents a generous survey of early modern French culture through a selection of more than a hundred printed items from the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. This collection, extending across a multitude of subject areas to highlight the many facets of the French cultural scene, builds on previous BnF-based releases through the inclusion of items from the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, a treasured part of the national library which houses numerous unique historic archives. Classical items, printed in France and often in French translation, reveal both a shared European heritage and the emergence of a distinctive French identity and culture. These include editions by France’s leading classical scholars such as Isaac Casaubon (1599- 1614), Michel de Marolles (1600-1681) and André Dacier (1651- 1722). Also featured are influential burlesques of classical literature such as a 1669 two-volume edition of Paul Scarron’s (1610-1660) Virgile travesty and a 1665 L’Ovide Bouffon by Louis Richer. Medieval items provide a look to a broader European culture and beyond, such as a 1678 edition of Petrarch’s prose in French translation, incunable editions of Jean Gerson and Lyon imprints of the works of the Islamic Golden Age physician Avicenna. Early modern French literary works are well-represented across the genres. Poetry includes a 1587 edition of Pierre Ronsard’s (1524-1585) Les Eclogues et Mascarades, an original 1686 printing of Balthazar de Bonnecorse’s (1631-1706) Lutrigot and versions of Ovid by the dramatist Thomas Corneille (1625-1709). -

Contemporary French Poetry, Intermedia, and Narrative

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Unidentified erbalV Objects: Contemporary French Poetry, Intermedia, and Narrative Eric Lynch Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/764 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] UNIDENTIFIED VERBAL OBJECTS: CONTEMPORARY FRENCH POETRY, INTERMEDIA, AND NARRATIVE by ERIC LYNCH A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Eric Lynch All Rights Reserved Lynch ii UNIDENTIFIED VERBAL OBJECTS: CONTEMPORARY FRENCH POETRY, INTERMEDIA, AND NARRATIVE by Eric Lynch This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in French to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. January 26, 2016 ____________________________________ Mary Ann Caws Chair of Examining Committee January 26, 2016 ____________________________________ Francesca Sautman Executive Officer ____________________________________ Peter Consenstein ____________________________________ Evelyne Ender Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Lynch iii Abstract UNIDENTIFIED VERBAL OBJECTS: CONTEMPORARY FRENCH POETRY, INTERMEDIA, AND NARRATIVE By Eric Lynch Adviser: Mary Ann Caws This dissertation examines the vital experimental French poetry of the 1980s to the present. Whereas earlier twentieth century poets often shunned common speech, poets today seek instead to appropriate, adapt, and reorganize a wide variety of contemporary discourses. -

Antikenrezeption in Corneilles Médée

8 Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen Sophie Kleinecke Antikenrezeption in Corneilles Médée ‘ Euripides , Senecas und Corneilles Medea-Tragödien Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen 8 Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen hrsg. von Dina De Rentiis, Albert Gier und Enrique Rodrigues-Moura Band 8 University of Bamberg Press 2013 Antikenrezeption in Corneilles Médée Euripides’, Senecas und Corneilles Medea-Tragödien Sophie Kleinecke University of Bamberg Press 2013 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informatio- nen sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de/ abrufbar Diese Studie wurde von der Philosophischen Fakultät I der Universität Würzburg als Dissertation angenommen 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Thomas Baier 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Erler Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 11.05.2012 Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über den Hochschulschriften- Server (OPUS; http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-bamberg/) der Universi- tätsbibliothek Bamberg erreichbar. Kopien und Ausdrucke dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden. Herstellung und Druck: docupoint GmbH, Barleben Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press, Andra Brandhofer © University of Bamberg Press Bamberg 2013 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 1867-5042 ISBN: 978-3-86309-142-2 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-143-9 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-35496 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort………………………………………………………………….……………….. S. 9 A. Einleitung……………..………………………………………..………………… S. 11 I. Corneilles Médée – ein Publikumserfolg?..………………………….… S. 11 II. Vorlagen für die Médée.……………………………………….………………. S. 12 III. Forschungslage und Vorgehen……….…………………………………..… S. 14 B. Das antike Drama: Euripides und Seneca……………………..…… S. 21 I. Euripides: das klassische attische Drama………………................. S. 21 II. Seneca: Silberne Latinität und Manierismus…………………………. -

Challenges to Traditional Authority: Plays by French Women Authors, 1650–1700

FRANÇOISE PASCAL, MARIE-CATHERINE DESJARDINS, ANTOINETTE DESHOULIÈRES, AND CATHERINE DURAND Challenges to Traditional Authority: Plays by French Women Authors, 1650–1700 • Edited and translated by PERRY GETHNER Iter Academic Press Toronto, Ontario Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Tempe, Arizona 2015 Iter Academic Press Tel: 416/978–7074 Email: [email protected] Fax: 416/978–1668 Web: www.itergateway.org Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Tel: 480/965–5900 Email: [email protected] Fax: 480/965–1681 Web: acmrs.org © 2015 Iter, Inc. and the Arizona Board of Regents for Arizona State University. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. Iter and the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies gratefully acknowledge the gener- ous support of James E. Rabil, in memory of Scottie W. Rabil, toward the publication of this book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Challenges to traditional authority : plays by French women authors, 1650-1700 / edited and trans- lated by Perry Gethner. pages cm. -- (Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies ; 477) (The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe ; The Toronto Series, 36) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-86698-530-7 (alk. paper) 1. French drama--Women authors. 2. French drama--17th century. I. Gethner, Perry, editor, translator. PQ1220.C48 2015 842’.40809287--dc23 2014049921 Cover illustration: Selene and Endymion, c.1630 (oil on canvas), Poussin, Nicolas (1594–1665) / Detroit Institute of Arts, USA / Founders Society purchase, -

Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2005 Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism Glenn W. Fetzer Calvin College Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Fetzer, Glenn W. (2005) "Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1591 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism Abstract Within the past decade, one of the most pressing questions of poetry in France has been the continuing viability of lyricism. Recent models of perceiving the nature of lyricism shift the focus from formal and thematic considerations to pragmatic ones. As Hocquard's Un test de solitude: sonnets (1998) and Gleize's Non (1999) illustrate, the challenge of the lyric today serves to sharpen the sense of alterity and gives evidence of lyricism's capacity for renewal. More specifically, in presenting a reading of sonnets from both writers, this paper shows that the debates on the nature and "recurrence" of lyricism foreground the relational mode, above all, and give witness to the capacity of the lyric to withstand, to test, and ultimately, to reinvent itself. -

Emmanuel Hocquard, Late Additions

Emmanuel Hocquard LATE ADDITIONS SERlE D'ECRITURE NO. TWO Serie d'ecriture no. 1: Alain Veinstein, Archeology of the Mother, 1986 Serie d'ecriture no. 2: Emmanuel Hocquard: Late Additions, 1988 Serie d'ecriture no. 3: magazine issue, forthcoming Serie d'ecriture is an irregularly produced journal given to English translations of current French writing. Issues given to the work of a single author will alternate with magazine issues. The journal is edited by Rosmarie Waldrop and pub lished, with the collaboration of Burning Deck, by: SPECTACULAR DISEASES c/o Paul Green 83 (b) London Road Peterborough, Cambs., PE2 9BS United Kingdom Individual copies are priced at Ll.SO, with subscriptions available at L2.00 for two issues. Postage should be added at 25p per copy in all instances. US price $3.50, with sub scriptions at $4.50 plus $2 postage for 2 issues. Distributed in the US by: Segue Distribution, 300 Bowery, New York, NY 10012 Small Press Distribution, 1814 San Pablo Ave., Berkeley, CA 94702 ISSN 0269 - 0179 Copyright (c) 1988 by Emmanuel Hocquard, Connell lV1cGrath and Rosmarie Waldrop Some of the translations in this issue were first printed in Acts, 0- blek and Verse. The editor and publisher regret the omission of credit for the cover of issue no.l, a montage by the Australian artist Denis Mizzi. The cover of this issue is by Raquel. SERlE D'ECRITURE No. 2: Emmanuel Hocquard LATE ADDITIONS translated from the French by Rosmarie Waldrop and Connell McGrath SPECTACULAR DISEASES 1988 24 November and the words: shadow of the last tree. -

Chicago Chicago Fall 2015

UNIV ERSIT Y O F CH ICAGO PRESS 1427 EAST 60TH STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60637 KS OO B LL FA CHICAGO 2015 CHICAGO FALL 2015 FALL Recently Published Fall 2015 Contents General Interest 1 Special Interest 50 Paperbacks 118 Blood Runs Green Invisible Distributed Books 145 The Murder That Transfixed Gilded The Dangerous Allure of the Unseen Age Chicago Philip Ball Gillian O’Brien ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23889-0 Author Index 412 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24895-0 Cloth $27.50/£19.50 Cloth $25.00/£17.50 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23892-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24900-1 COBE/EU Title Index 414 Subject Index 416 Ordering Inside Information back cover Infested Elephant Don How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse Bedrooms and Took Over the World Caitlin O’Connell Brooke Borel ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10611-3 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04193-3 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10625-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04209-1 Plankton Say No to the Devil Cover illustration: Lauren Nassef Wonders of the Drifting World The Life and Musical Genius of Cover design by Mary Shanahan Christian Sardet Rev. Gary Davis Catalog design by Alice Reimann and Mary Shanahan ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18871-3 Ian Zack Cloth $45.00/£31.50 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23410-6 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-26534-6 Cloth $30.00/£21.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23424-3 JESSA CRISPIN The Dead Ladies Project Exiles, Expats, and Ex-Countries hen Jessa Crispin was thirty, she burned her settled Chica- go life to the ground and took off for Berlin with a pair of W suitcases and no plan beyond leaving. -

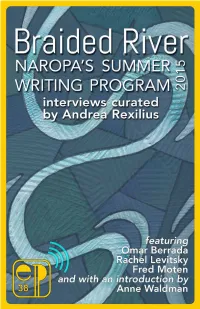

Rexilluslt Spreads1 .Pdf

BRAIDED RIVER interviews curated by ANDREA REXILIUS #38 ESSAY PRESS LISTENING TOUR As the Essay Press website re-launches, we have commissioned some of our favorite conveners of public discussions to curate conversation-based CONTENTS chapbooks. Overhearing such dialogues among poets, prose writers, critics and artists, we hope to re-envision how Essay can emulate and expand upon recent developments in trans-disciplinary small-press culture. Introduction v by Anne Waldman Series Editors Maria Anderson Interview with Rachel Levitsky 1 Andy Fitch Interview with Fred Moten 20 Ellen Fogelman Aimee Harrison Interview with Omar Berrada 24 Courtney Mandryk Afterword 46 Victoria A. Sanz by Andrea Rexilius Travis Sharp Acknowledgments 50 Ryan Spooner Randall Tyrone About Naropa 2016 51 Author Bios 52 Series Assistants Cristiana Baik Ryan Ikeda Christopher Liek Cover Image Courtesy of Jane Dalrymple-Hollo Cover Design Courtney Mandryk Layout Aimee Harrison INTRODUCTION — Anne Waldman SWP Artistic Directior hese are three interviews, the same questions Tfor three eminent, wildly progressive poets who have been guest faculty during Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics Summer Writing Program—all visiting/teaching/performing at Naropa before these conversations took place, but queried here specifically in the context of our 2015 pedagogy, which carried the themic rubric of Braided River, the Activist Rhizome. Symbiosis (= “together living”) teaches that life is more like a braided river, horizontal waterflow with tributaries falling apart and coming together again (as algae, as fungi do), rather than the Abrahamic tree of life with its vertical, hierarchical branch system. We are the riparians alongside, inside, riding this river of inter- connectivity. -

![Excerpt from Navidad Nuestra [Nah-Vee-THAD Nooayss-Trah]; Music by Ariel Ramírez [Ah-Reeell Rah-MEE-Rehth] and Text by F](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8962/excerpt-from-navidad-nuestra-nah-vee-thad-nooayss-trah-music-by-ariel-ram%C3%ADrez-ah-reeell-rah-mee-rehth-and-text-by-f-3038962.webp)

Excerpt from Navidad Nuestra [Nah-Vee-THAD Nooayss-Trah]; Music by Ariel Ramírez [Ah-Reeell Rah-MEE-Rehth] and Text by F

La anunciacion C La anunciación C lah ah-noon-theeah-theeAWN C (excerpt from Navidad nuestra [nah-vee-THAD nooAYSS-trah]; music by Ariel Ramírez [ah-reeELL rah-MEE-rehth] and text by F. Luna [(F.) LOO-nah]) La barca C lah BAR-kah C (The Boat) C (excerpt from the suite Impresiones intimas [eem- prayss-YO-nayss een-TEE-mahss] — Intimate Impressions — by Federico Mompou [feh- theh-REE-ko mawm-POOO]) La barcheta C lah bar-KAY-tah C (The Little Boat) C (composition by Hahn [HAHN]) La bas dans le limousin C Là-bas dans le Limousin C lah-bah dah6 luh lee-môô-zeh6 C (excerpt from Chants d'Auvergne [shah6 doh-vehrny’] — Songs of the Auvergne [o-vehrny’], French folk songs collected by Joseph Canteloube [zho-zeff kah6-t’lôôb]) La bas vers leglise C Là-bas, vers l'église C lah-bah, vehr lay-gleez C (excerpt from Cinq mélodies populaires grecques [seh6k may-law-dee paw-pü-lehr greck] — Five Popular Greek Melodies — by Maurice Ravel [mo-reess rah-vell]) La belle helene C La belle Hélène C lah bell ay-lenn C (The Fair Helen) C (an opera, with music by Jacques Offenbach [ZHACK AWF-funn-bahk]; libretto by Henri Meilhac [ah6-ree meh-yack] and Ludovic Halévy [lü-daw-veek ah-lay-vee]) La belle isabeau conte pendant lorage C La belle Isabeau (Conte pendant l’orage) C lah bell ee- zah-bo (kaw6t pah6-dah6 law-rahzh) C (The Lovely Isabeau (Tale During a Storm)) C (poem by Alexandre Dumas [ah-leck-sah6-dr’ dü-mah] set to music by Hector Berlioz [eck-tawr behr-leeawz]) La belle se sied au pied de la tour C lah bell s’-seeeh o peeeh duh lah tôôr C (The Fair Maid -

A History of French Literature from Chanson De Geste to Cinema

A History of French Literature From Chanson de geste to Cinema DAVID COWARD HH A History of French Literature For Olive A History of French Literature From Chanson de geste to Cinema DAVID COWARD © 2002, 2004 by David Coward 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of David Coward to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2002 First published in paperback 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coward, David. A history of French literature / David Coward. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–631–16758–7 (hardback); ISBN 1–4051–1736–2 (paperback) 1. French literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PQ103.C67 2002 840.9—dc21 2001004353 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. 1 Set in 10/13 /2pt Meridian by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com Contents -

Norma Cole Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8k077nv No online items Norma Cole Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2015 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Norma Cole Papers MSS 0766 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Norma Cole Papers Creator: Cole, Norma Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0766 Physical Description: 36 Linear feet(84 archives boxes, 4 card file boxes, 1 flat box, and 1 map case folder) Date (inclusive): 1940-2014 (bulk 1985-2014) Abstract: Papers of poet, artist and translator Norma Cole. Cole lived and worked in the San Francisco Bay Area and collaborated with American, French and Canadian poets. The collection includes correspondence, manuscripts, notebooks, translations, photographs, negatives, sound and video recordings, digital media, artwork and ephemera. Scope and Content of Collection Papers of poet, artist and translator Norma Cole. Cole lived and worked in the San Francisco Bay Area and collaborated with American, French and Canadian poets. The collection contains correspondence, manuscripts, notebooks, translations, photographs, negatives, sound and video recordings, digital media, artwork and ephemera. Arranged in thirteen series: 1) BIOGRAPHICAL, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS BY COLE, 4) COLLABORATIVE WORKS, 5) WORKS BY OTHERS, 6) TRANSLATIONS, 7) ARTWORK, 8) EPHEMERA, 9) SUBJECT FILES, 10) PHOTOGRAPHS 11) SOUND RECORDINGS, 12) VIDEO RECORDINGS and 13) DIGITAL MEDIA. Biography Poet, translator, visual artist and curator Norma Cole was born in Toronto, Canada on May 12, 1945. -

Medea Und Médée Senecas Drama Im Vergleich Mit Dem Opernlibretto Thomas Corneilles

Medea und Médée Senecas Drama im Vergleich mit dem Opernlibretto Thomas Corneilles Wissenschaftliche Hausarbeit zur Ersten Staatsprüfung für das Amt des Studienrats Vorgelegt von: Valérie Sinn Latein/Französisch Berlin, 17.2.2005 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung........................................................................................................... 4 2 Die Autoren und ihr Werk .................................................................................. 5 2.1 Seneca ...................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Marc-Antoine Charpentier und Thomas Corneille..................................... 10 3 Vergleich des Aufbaus und der Personengestaltung........................................ 15 3.1 Aufbau der Werke .................................................................................... 15 3.2 Die Charaktere......................................................................................... 22 3.2.1 Medea/Médée .................................................................................. 22 3.2.2 Iason/Jason...................................................................................... 30 3.2.3 Creo/Créon ...................................................................................... 38 4 Die Rache........................................................................................................ 45 4.1 Warum rächt sich Medea/Médée? ........................................................... 46 4.1.1 Gründe ............................................................................................