Literality: the Question of Contemporary Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary French Poetry, Intermedia, and Narrative

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Unidentified erbalV Objects: Contemporary French Poetry, Intermedia, and Narrative Eric Lynch Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/764 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] UNIDENTIFIED VERBAL OBJECTS: CONTEMPORARY FRENCH POETRY, INTERMEDIA, AND NARRATIVE by ERIC LYNCH A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Eric Lynch All Rights Reserved Lynch ii UNIDENTIFIED VERBAL OBJECTS: CONTEMPORARY FRENCH POETRY, INTERMEDIA, AND NARRATIVE by Eric Lynch This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in French to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. January 26, 2016 ____________________________________ Mary Ann Caws Chair of Examining Committee January 26, 2016 ____________________________________ Francesca Sautman Executive Officer ____________________________________ Peter Consenstein ____________________________________ Evelyne Ender Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Lynch iii Abstract UNIDENTIFIED VERBAL OBJECTS: CONTEMPORARY FRENCH POETRY, INTERMEDIA, AND NARRATIVE By Eric Lynch Adviser: Mary Ann Caws This dissertation examines the vital experimental French poetry of the 1980s to the present. Whereas earlier twentieth century poets often shunned common speech, poets today seek instead to appropriate, adapt, and reorganize a wide variety of contemporary discourses. -

Ac Know Ledg Ments

A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s In the course of my research, Robert Duncan’s friends, without exception, granted me a share in the generosity, goodwill, and love for life that so char- acterized his being. Two people made a special eff ort to help me understand Robert Duncan’s “dailiness,” and their insights were key factors in the making of this book. Jess Collins agreed that it was an appropriate time for a biography of Duncan to be written, and he welcomed me into his life for a little bit over a de cade, allowing me to experience the rituals of house hold that he had shared with Duncan. Barbara Jones and her family in Bakersfi eld, California, extended me great hospitality. Barbara’s memories of her brother as a child and of their life in the San Joaquin Valley were in all ways illuminating. Th eir insights were key factors in the making of this book. Th is book was also made possible through the ongoing tireless support of my husband, Th omas Evans. His own studies of Jess, Duncan, and the West Coast assemblage artists contributed at every turn to the thoroughness of this book. His companionship allows me to live in a house hold as rich as Jess and Duncan’s. I am grateful to Robert Duncan’s friends, family, students and acquaintances: Gerald Ackerman, Robert Adamson, the late Virginia Admiral, Charles Alexander, the late Donald Allen, Michael Anania, Bruce Andrews, Norman Austin, Todd Baron, Dawn Michelle Baude, Tosh Berman, Charles Bern- stein, Robert Bertholf, the late Robin Blaser, Richard Blevins, George Bower- ing, the late Stan Brakhage, the late David Bromige, the late James Brough- ton, the late Norman O. -

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California Edited by Patrick James Dunagan Marina Lazzara Nicholas James Whittington Series in Creative Writing Studies Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Creative Writing Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935054 ISBN: 978-1-62273-800-7 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Max Kirkeberg, diva.sfsu.edu/collections/kirkeberg/bundles/231645 All individual works herein are used with permission, copyright owned by their authors. Selections from "Basic Elements of Poetry: Lecture Notes from Robert Duncan Class at New College of California," Robert Duncan are © the Jess Collins Trust. -

Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2005 Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism Glenn W. Fetzer Calvin College Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Fetzer, Glenn W. (2005) "Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1591 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism Abstract Within the past decade, one of the most pressing questions of poetry in France has been the continuing viability of lyricism. Recent models of perceiving the nature of lyricism shift the focus from formal and thematic considerations to pragmatic ones. As Hocquard's Un test de solitude: sonnets (1998) and Gleize's Non (1999) illustrate, the challenge of the lyric today serves to sharpen the sense of alterity and gives evidence of lyricism's capacity for renewal. More specifically, in presenting a reading of sonnets from both writers, this paper shows that the debates on the nature and "recurrence" of lyricism foreground the relational mode, above all, and give witness to the capacity of the lyric to withstand, to test, and ultimately, to reinvent itself. -

Emmanuel Hocquard, Late Additions

Emmanuel Hocquard LATE ADDITIONS SERlE D'ECRITURE NO. TWO Serie d'ecriture no. 1: Alain Veinstein, Archeology of the Mother, 1986 Serie d'ecriture no. 2: Emmanuel Hocquard: Late Additions, 1988 Serie d'ecriture no. 3: magazine issue, forthcoming Serie d'ecriture is an irregularly produced journal given to English translations of current French writing. Issues given to the work of a single author will alternate with magazine issues. The journal is edited by Rosmarie Waldrop and pub lished, with the collaboration of Burning Deck, by: SPECTACULAR DISEASES c/o Paul Green 83 (b) London Road Peterborough, Cambs., PE2 9BS United Kingdom Individual copies are priced at Ll.SO, with subscriptions available at L2.00 for two issues. Postage should be added at 25p per copy in all instances. US price $3.50, with sub scriptions at $4.50 plus $2 postage for 2 issues. Distributed in the US by: Segue Distribution, 300 Bowery, New York, NY 10012 Small Press Distribution, 1814 San Pablo Ave., Berkeley, CA 94702 ISSN 0269 - 0179 Copyright (c) 1988 by Emmanuel Hocquard, Connell lV1cGrath and Rosmarie Waldrop Some of the translations in this issue were first printed in Acts, 0- blek and Verse. The editor and publisher regret the omission of credit for the cover of issue no.l, a montage by the Australian artist Denis Mizzi. The cover of this issue is by Raquel. SERlE D'ECRITURE No. 2: Emmanuel Hocquard LATE ADDITIONS translated from the French by Rosmarie Waldrop and Connell McGrath SPECTACULAR DISEASES 1988 24 November and the words: shadow of the last tree. -

Chicago Chicago Fall 2015

UNIV ERSIT Y O F CH ICAGO PRESS 1427 EAST 60TH STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60637 KS OO B LL FA CHICAGO 2015 CHICAGO FALL 2015 FALL Recently Published Fall 2015 Contents General Interest 1 Special Interest 50 Paperbacks 118 Blood Runs Green Invisible Distributed Books 145 The Murder That Transfixed Gilded The Dangerous Allure of the Unseen Age Chicago Philip Ball Gillian O’Brien ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23889-0 Author Index 412 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24895-0 Cloth $27.50/£19.50 Cloth $25.00/£17.50 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23892-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24900-1 COBE/EU Title Index 414 Subject Index 416 Ordering Inside Information back cover Infested Elephant Don How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse Bedrooms and Took Over the World Caitlin O’Connell Brooke Borel ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10611-3 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04193-3 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10625-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04209-1 Plankton Say No to the Devil Cover illustration: Lauren Nassef Wonders of the Drifting World The Life and Musical Genius of Cover design by Mary Shanahan Christian Sardet Rev. Gary Davis Catalog design by Alice Reimann and Mary Shanahan ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18871-3 Ian Zack Cloth $45.00/£31.50 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23410-6 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-26534-6 Cloth $30.00/£21.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23424-3 JESSA CRISPIN The Dead Ladies Project Exiles, Expats, and Ex-Countries hen Jessa Crispin was thirty, she burned her settled Chica- go life to the ground and took off for Berlin with a pair of W suitcases and no plan beyond leaving. -

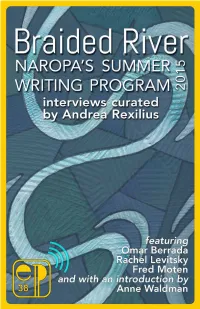

Rexilluslt Spreads1 .Pdf

BRAIDED RIVER interviews curated by ANDREA REXILIUS #38 ESSAY PRESS LISTENING TOUR As the Essay Press website re-launches, we have commissioned some of our favorite conveners of public discussions to curate conversation-based CONTENTS chapbooks. Overhearing such dialogues among poets, prose writers, critics and artists, we hope to re-envision how Essay can emulate and expand upon recent developments in trans-disciplinary small-press culture. Introduction v by Anne Waldman Series Editors Maria Anderson Interview with Rachel Levitsky 1 Andy Fitch Interview with Fred Moten 20 Ellen Fogelman Aimee Harrison Interview with Omar Berrada 24 Courtney Mandryk Afterword 46 Victoria A. Sanz by Andrea Rexilius Travis Sharp Acknowledgments 50 Ryan Spooner Randall Tyrone About Naropa 2016 51 Author Bios 52 Series Assistants Cristiana Baik Ryan Ikeda Christopher Liek Cover Image Courtesy of Jane Dalrymple-Hollo Cover Design Courtney Mandryk Layout Aimee Harrison INTRODUCTION — Anne Waldman SWP Artistic Directior hese are three interviews, the same questions Tfor three eminent, wildly progressive poets who have been guest faculty during Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics Summer Writing Program—all visiting/teaching/performing at Naropa before these conversations took place, but queried here specifically in the context of our 2015 pedagogy, which carried the themic rubric of Braided River, the Activist Rhizome. Symbiosis (= “together living”) teaches that life is more like a braided river, horizontal waterflow with tributaries falling apart and coming together again (as algae, as fungi do), rather than the Abrahamic tree of life with its vertical, hierarchical branch system. We are the riparians alongside, inside, riding this river of inter- connectivity. -

Ii Table of Contents GENERAL INTRODUCTION to THE

Table of Contents GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE PROGRAM 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Brief History of the Program ………………………………………..1-2 1.2 Brief Synopsis of Previous Program Review Recommendations……2-5 1.3 Summary of How Program Meets the Standards…………………….6-7 1.4 Summary of Present Program Review Recommendations…………..7-8 2.0 PROFILE OF THE PROGRAMS AND DISCIPLINES 2.1 Overview of the Programs and Disciplines…………………………8-17 2.2 The Programs in the Context of the Academic Unit………………..17-22 HOW PROGRAM MEETS UNIVERSITY WIDE INDICATORS AND STANDARDS 3.0 ADMISSIONS REQUIREMENTS 3.1 Evidence of Prior Academic Success……………………………….22 3.2 Evidence of Competent Writing…………………………………….22 3.3 English Preparation of Non-Native Speakers……………………….23 3.4 Overview of Program Admissions Policy…………………………..23 4.0 PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS 4.1 Number of Course Offerings………………………………………..24 4.2 Frequency of Course Offerings…………………………………….24 4.3 Path to Graduation………………………………………………….24 4.4 Course Distribution on ATC………………………………………..25 4.5 Class Size…………………………………………………………...25 4.6 Number of Graduates……………………………………………….25 4.7 Overview of Program Quality and Sustainability Indicators……….25-26 5.0 FACULTY REQUIREMENTS 5.1 Number of Faculty in Graduate Programs…………………………..26-27 5.2 Number of Faculty per Concentration……………………………....27 6.0 PROGRAM PLANNING AND QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROCESS…27-29 7.0 THE STUDENT EXPERIENCE 7.1 Student Statistics……………………………………………………29-31 7.2 Assessment of Student Learning……………………………………31-34 7.3 Advising…………………………………………………………….34-35 7.4 Writing Proficiency…………………………………………………35 -

Norma Cole Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8k077nv No online items Norma Cole Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2015 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Norma Cole Papers MSS 0766 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Norma Cole Papers Creator: Cole, Norma Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0766 Physical Description: 36 Linear feet(84 archives boxes, 4 card file boxes, 1 flat box, and 1 map case folder) Date (inclusive): 1940-2014 (bulk 1985-2014) Abstract: Papers of poet, artist and translator Norma Cole. Cole lived and worked in the San Francisco Bay Area and collaborated with American, French and Canadian poets. The collection includes correspondence, manuscripts, notebooks, translations, photographs, negatives, sound and video recordings, digital media, artwork and ephemera. Scope and Content of Collection Papers of poet, artist and translator Norma Cole. Cole lived and worked in the San Francisco Bay Area and collaborated with American, French and Canadian poets. The collection contains correspondence, manuscripts, notebooks, translations, photographs, negatives, sound and video recordings, digital media, artwork and ephemera. Arranged in thirteen series: 1) BIOGRAPHICAL, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS BY COLE, 4) COLLABORATIVE WORKS, 5) WORKS BY OTHERS, 6) TRANSLATIONS, 7) ARTWORK, 8) EPHEMERA, 9) SUBJECT FILES, 10) PHOTOGRAPHS 11) SOUND RECORDINGS, 12) VIDEO RECORDINGS and 13) DIGITAL MEDIA. Biography Poet, translator, visual artist and curator Norma Cole was born in Toronto, Canada on May 12, 1945. -

1 DISSERTATIONS in PROGRESS Compiled And

DISSERTATIONS IN PROGRESS Compiled and Edited by Madeline Turan, Stony Brook University This is the forty-ninth annual listing of doctoral dissertations from graduate programs in North America. It should be considered a supplement of preceding lists. Defended dissertations are listed as a separate section, after the “Dissertations in Progress” list. The dissertation titles are listed alphabetically under “Cultural Studies,” “Film Studies,” “Linguistics,” “Literature,” or “Pedagogy”. Literature dissertations are arranged by century and author or are listed under “General.” There is also a separate section for Francophone authors and topics. In each entry, the name of the dissertation director and that of the institution are given in parentheses. Titles are numbered consecutively within each section. Title changes are noted at the end of each section, showing the number of the dissertation as it was previously listed, followed by the new title. It should be noted that, in general, the information was compiled as submitted by each institution. We regret that titles from a few schools were not received in time for publication. DISSERTATIONS IN PROGRESS (2012) A. CULTURAL STUDIES 88. Comic Memory: Franco-Algerian Relations through Humor (1954–2012). Sandra Rousseau (Jennifer A. Boittin, Pennsylvania State University) 89. Cuisine and the French Social Imaginary: Tracing the Origins of Gastronomic Discourse in Early-19th-Century France. Maximillian Shrem (Anne Deneys- Tunney, New York University) 90. Designing Women: Fashion and Fiction in Second Empire France. Sara Phenix (Andrea Goulet, University of Pennsylvania) 91. Intellectuel résistant: l’anti-impérialisme contestataire de Claude Bourdet dans l’après-guerre. Fabrice Picon (Jennifer Boittin, Pennsylvania State University) 92. -

Poet-Translators in Nineteenth Century French Literature: Nerval, Baudelaire, Mallarmé” Dir

POET-TRANSLATORS IN NINETEENTH CENTURY FRENCH LITERATURE: NERVAL, BAUDELAIRE, MALLARMÉ by Jena Whitaker A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland April 2018 Ó 2018 Jena Whitaker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The ‘poet-translator is a listener whose ears are transformed through translation. The ear not only relates to the sensorial, but also to the cultural and historical. This dissertation argues that the ‘poet-translator,’ whose ears encounter a foreign tongue discovers three new rhythms: a new linguistic rhythm, a new cultural rhythm, and a new experiential rhythm. The discovery of these different rhythms has a pronounced impact on the poet-translator’s poetics. In this case, poetics does not refer to the work of art, but instead to an activity. It therefore concerns the reader’s will to listen to what a text does and to understand how it works. Although the notion of the ‘poet-translator’ pertains to a wide number of writers, time periods, and fields of study, this dissertation focuses on three nineteenth-century ‘poet-translators’ who each partly as a result of their contact with German romanticism formed an innovative and fresh account of linguistic, cultural, and poetic rhythm: Gérard de Nerval (1808-1855), Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), and Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898). Each of these ‘poet-translators acted as cultural mediators, contributing to the development of new literary genres and new forms of critique that came to have significant effects on Western Literature. A study of Nerval, Baudelaire and Mallarmé as ‘poet-translators’ is historically pertinent for at least four reasons. -

''Creeley's Reception in France''

”Creeley’s Reception in France” Lang Abigail To cite this version: Lang Abigail. ”Creeley’s Reception in France”. Formes Poétiques Contemporaines, Presses Universi- taires du Nouveau Monde, 2016, 12. hal-01418922 HAL Id: hal-01418922 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01418922 Submitted on 24 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Abigail Lang Université Paris-Diderot (LARCA-UMR 8225) Creeley’s reception in France1 Although Robert Creeley seemed keen to appear as a « uniquely American persona, »2 to associate himself with what he calls « the Americanism of certain painters, like Pollock », « specifically American in their ways of experiencing activity, with energy a process, »3 some of the earliest influences he acknowledges are European, and particularly French: the Existentialists, André Gide, but above all Stendhal whom he admires for « the incredible clarity and fluidity of his thinking »4 and for his sparse use of words. Robert Duncan, one of his most attentive readers, suggests Creeley refrained from reading Barthes because it was « too close for comfort, »5 and Joshua Watsky has convincingly demonstrated that Creeley made his decisive encounter with abstraction in front of René Laubiès’s canvasses rather than Pollock’s, a fact confirmed by Creeley’s excited letter of May 25, 1952 to Olson.6 While there is ample material to substantiate a French influence on Creeley, I will here focus on Creeley’s own reception in France, beginning with a general overview and then focusing on a case-study: Jean Daive’s encounter with Creeley’s work.