''Creeley's Reception in France''

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Poets Museletter

Frank Moulton Wisconsin Fellowship founded 1950 Of Poets President MuseletterVice-President Secretary Treasurer Membership Chair Peter Sherrill Cathryn Cofell Roberta Fabiani D.B. Appleton Karla Huston 8605 County Road D 736 W. Prospect Avenue 407 Dale Drive 720 E. Gorham St. #402 1830 W. Glendale Ave. Forestville, WI 54213 Appleton, WI 54914 Burlington, WI 53105 Madison, WI 53703 Appleton, WI 54914 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Summer 2003 www.wfop.org Editor: Christine Falk President’s Message First, thanks to the Mid-Central conference committee for such a wonderful Spring Conference: regional vice-president Joan Johannes and committee members Jeffrey Johannes, Lucy Rose Johns, Casey Martin, Grace Bushman, Barbara Cranford, Mary Lou Judy, Linda Aschbrenner, Phil Hansotia, Kris Rued- Welcome to the following new Clark, Gloria Federwitz, and Bruce Dethlefsen. The organization was excellent, members of the Wisconsin Fellowship the hotel first-rate (and a very respectable room rate, at that!) And the program of Poets that have joined since the inspiring. Spring Museletter issue: In addition to the traditional Friday-night Open Mic, and the Saturday Roll Call Poems, presenters Bill Weise and James Lee livened up the afternoon. Bill Weise Kristin Alberts Brussels blended music, drumming and audience participation in his demonstration on Edward DiMaio Egg Harbor using the spiritual energy inside us to open new creative possibilities. James Lee, Earle Garber Wisconsin Rapids Daniel Greene Smith Madison award-winning Madison poet, recited from his own high-energy works and used Kathleen Grieger Menomonee Falls audience-generated images in a spontaneous performance poem at the end of his Lincoln Hartford New Lisbon presentation. -

An Oral Interpretation Script Illustrating the Influence

379 AN ORAL INTERPRETATION SCRIPT ILLUSTRATING THE INFLUENCE ON CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POETRY OF THE THREE BLACK MOUNTAIN POETS: CHARLES OLSON, ROBERT CREELEY, ROBERT DUNCAN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By H. Vance James, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1981 J r James, H. Vance, An Oral Interpretation Script Illustrating the Influence on Contemporary American Poetry of the Three Black Mountain Poets: Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan. Master of Science (Speech Communication and Drama), August, 1981, 87 pp., bibliography, 23 titles. This oral interpretation thesis analyzes the impact that three poets from Black Mountain College had on contemporary American poetry. The study concentrates on the lives, works, poetic theories of Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and Robert Duncan and culminates in a lecture recital compiled from historical data relating to Black Mountain College and to the three prominent poets. @ 1981 HAREL VANCE JAMES All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 History of Black Mountain College Purpose of the Study Procedure II. BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION . 12 Introduction Charles Olson Robert Creeley Robert Duncan III. ANALYSIS . 31 IV. LECTURE RECITAL . 45 The Black Mountain Poets: Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan "These Days" (Olson) "The Conspiracy" (Creeley) "Come, Let Me Free Myself" (Duncan) "Thank You For Love" (Creeley) "The Door" (Creeley) "Letter 22" (Olson) "The Dance" (Duncan) "The Awakening" (Creeley) "Maximus, To Himself" (Olson) "Words" (Creeley) "Oh No" (Creeley) "The Kingfishers" (Olson) "These Days" (Olson) APPENDIX . -

Poem on the Page: a Collection of Broadsides

Granary Books and Jeff Maser, Bookseller are pleased to announce Poem on the Page: A Collection of Broadsides Robert Creeley. For Benny and Sabina. 15 1/8 x 15 1/8 inches. Photograph by Ann Charters. Portents 18. Portents, 1970. BROADSIDES PROLIFERATED during the small press and mimeograph era as a logical offshoot of poets assuming control of their means of publication. When technology evolved from typewriter, stencil, and mimeo machine to moveable type and sophisticated printing, broadsides provided a site for innovation with design and materials that might not be appropriate for an entire pamphlet or book; thus, they occupy a very specific place within literary and print culture. Poem on the Page: A Collection of Broadsides includes approximately 500 broadsides from a diverse range of poets, printers, designers, and publishers. It is a unique document of a particular aspect of the small press movement as well as a valuable resource for research into the intersection of poetry and printing. See below for a list of some of the poets, writers, printers, typographers, and publishers included in the collection. Selected Highlights from the Collection Lewis MacAdams. A Birthday Greeting. 11 x 17 Antonin Artaud. Indian Culture. 16 x 24 inches. inches. This is no. 90, from an unstated edition, Translated from the French by Clayton Eshleman signed. N.p., n.d. and Bernard Bador with art work by Nancy Spero. This is no. 65 from an edition of 150 numbered and signed by Eshleman and Spero. OtherWind Press, n.d. Lyn Hejinian. The Guard. 9 1/4 x 18 inches. -

Living Into Robert Creeley's Poetics Robert J. Bertholf It

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 27 (2008) : 9-49 And Then He Bought Some Lettuce: Living into Robert Creeley’s Poetics Robert J. Bertholf It must have been the fall semester 1963 when Robert Creeley came to Eugene to give a reading at the University of Oregon. For Love: Poems 1950–1960 had been published the year before. The writing program at the school held generous views about Creeley’s poetry and For Love had already brought in equally generous reviews. I went to the reading with great anticipation, mainly because as a second-year graduate student I was feeling free from Longfellow, Hawthorne and what I thought of as the pernicious New England mind; this was a chance to hear a poet speak directly to an audience and to get a sense of what was being talked about as the “New American Poetry.” The reading began with enthusiasm and went on with the high energy of Creeley’s tightly stretched observations about here and there, the isolation of self and longing for a community, the cry for the commune of love, and the insistence for exploring the abilities of language to express thought. About half way through the reading I was flooded with the terrifying anxiety that Creeley was propounding ways of seeing and thinking that I had fled New England to escape. “This guy’s from New England,” I said to a friend sitting beside me, and left. Creeley’s remark on the subject read years later would not have given me much comfort after leaving the reading: At various times I’ve put emphasis on the fact that I was raised in New England, in Massachusetts for the most part. -

William Bronk

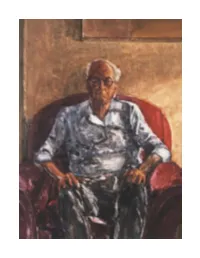

Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk David Clippinger Argotist Ebooks 2 * Cover image by Daniel Leary Copyright © David Clippinger 2012 All rights reserved Argotist Ebooks * Bill in a Red Chair, monotype, 20” x 16” © Daniel Leary 1997 3 The surest, and often the only, way by which a crowd can preserve itself lies in the existence of a second crowd to which it is related. Whether the two crowds confront each other as rivals in a game, or as a serious threat to each other, the sight, or simply the powerful image of the second crowd, prevents the disintegration of the first. As long as all eyes are turned in the direction of the eyes opposite, knee will stand locked by knee; as long as all ears are listening for the expected shout from the other side, arms will move to a common rhythm. (Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power) 4 Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk 5 Part I “So Large in His Singleness” By 1960 William Bronk had published a collection, Light and Dark (1956), and his poems had appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, Origin, and Black Mountain Review. More, Bronk had earned the admiration of George Oppen and Charles Olson, as well as Cid Corman, editor of Origin, James Weil, editor of Elizabeth Press, and Robert Creeley. But given the rendering of the late 1950s and early 1960s poetry scene as crystallized by literary history, Bronk seems to be wholly absent—a veritable lacuna in the annals of poetry. -

Ac Know Ledg Ments

A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s In the course of my research, Robert Duncan’s friends, without exception, granted me a share in the generosity, goodwill, and love for life that so char- acterized his being. Two people made a special eff ort to help me understand Robert Duncan’s “dailiness,” and their insights were key factors in the making of this book. Jess Collins agreed that it was an appropriate time for a biography of Duncan to be written, and he welcomed me into his life for a little bit over a de cade, allowing me to experience the rituals of house hold that he had shared with Duncan. Barbara Jones and her family in Bakersfi eld, California, extended me great hospitality. Barbara’s memories of her brother as a child and of their life in the San Joaquin Valley were in all ways illuminating. Th eir insights were key factors in the making of this book. Th is book was also made possible through the ongoing tireless support of my husband, Th omas Evans. His own studies of Jess, Duncan, and the West Coast assemblage artists contributed at every turn to the thoroughness of this book. His companionship allows me to live in a house hold as rich as Jess and Duncan’s. I am grateful to Robert Duncan’s friends, family, students and acquaintances: Gerald Ackerman, Robert Adamson, the late Virginia Admiral, Charles Alexander, the late Donald Allen, Michael Anania, Bruce Andrews, Norman Austin, Todd Baron, Dawn Michelle Baude, Tosh Berman, Charles Bern- stein, Robert Bertholf, the late Robin Blaser, Richard Blevins, George Bower- ing, the late Stan Brakhage, the late David Bromige, the late James Brough- ton, the late Norman O. -

Imc Robert Creeley

^IMC ROBERT CREELEY: A WRITING BIOGRAPHY AND INVENTORY by GERALDINE MARY NOVIK B.A., University of British Columbia, 1966 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February, 1973 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ENGLISH The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date February 7, 1973 ABSTRACT Now, in 1973, it is possible to say that Robert Creeley is a major American poet. The Inventory of works by and about Creeley which comprises more than half of this dissertation documents the publication process that brought him to this stature. The companion Writing Biography establishes Creeley additionally as the key impulse in the new American writing movement that found its first outlet in Origin, Black Mountain Review, Divers Books, Jargon Books, and other alternative little magazines and presses in the fifties. After the second world war a new generation of writers began to define themselves in opposition to the New Criticism and academic poetry then prevalent and in support of Pound and Williams, and as these writers started to appear in tentative little magazines a further definition took place. -

251 Poetry Warrior: Robert Creeley in His Letters

ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU POETRY WARRIOR: ROBERT CREELEY IN HIS LETTERS Creeley, Robert. The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley, ed. Rod Smith, Peter Baker, and Kaplan Harris. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014. Robert Archambeau “The book,” wrote Robert Creeley to Rod Smith, who was then hard at work on the volume in question, Creeley’s Selected Letters, “will certainly ‘tell a story.’” Now that the text of that book has emerged from Smith’s laptop and rests between hard covers, it’s a good time to ask just what story those letters tell. Certainly it isn’t a personal one. Creeley was a New Englander, through and through, and of the silent generation to boot. Yankee reticence blankets the letters too thickly for us to feel much of the texture of Creeley’s quotidian life, beyond whether he feels (to use his favored idiom) he’s “mak- ing it” through the times or not. Instead, the letters, taken together, tell an intensely literary story—and, as the plot develops, an institutional, academic one. Call this story “From the Outside In,” maybe. Or, better, treat it as one of the many Rashomon-like eyewitness accounts of that contentious epic that goes by the title The Poetry Wars. If, like me, you entered the little world of American poetry in the 1990s, you found the Cold War that was ending in the realm of politics to be in full effect in poetry. What had begun as a brushfire conflict between rival journals and anthologies in the fifties and early sixties had settled into an institutionalized rivalry, with an Iron Curtain drawn between the mutu- ally suspicious empires of Iowa City and Buffalo. -

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California Edited by Patrick James Dunagan Marina Lazzara Nicholas James Whittington Series in Creative Writing Studies Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Creative Writing Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935054 ISBN: 978-1-62273-800-7 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Max Kirkeberg, diva.sfsu.edu/collections/kirkeberg/bundles/231645 All individual works herein are used with permission, copyright owned by their authors. Selections from "Basic Elements of Poetry: Lecture Notes from Robert Duncan Class at New College of California," Robert Duncan are © the Jess Collins Trust. -

Jonathan Williams, Including Reviews of the Lord of Orchards

Reviews and comments about Jonathan Williams, including reviews of The Lord of Orchards: The Truffle-Hound of American Poetry Jeffery’s official obituary of Jonathan Williams as published in the Asheville Poetry Review, on the North Carolina Arts Council website, and elsewhere, 2008-2010. Jonathan Williams: The Lord of Orchards Indy Week Top Ten Fall Book Releases September 2017. Readings in the Triangle of North Carolina chosen as Our Pick by Indy Week, November 2017. “A not-to-be-missed Festschrift commemorating this witty avant-garde publisher, photographer and man of letters. —Washington Post reviewer Michael Dirda in his holiday 2018 list “Forget trendy bestsellers: This best books list takes you off the beaten track”, November 28, 2018. When I hear the word "bluets," I tend to think not of Maggie Nelson's widely adored lyric essay, but rather of Jonathan Williams. His 1985 book, Blues and Roots/Rue and Bluets: A Garland for the Southern Appalachians, is a paean to the landscape that held and compelled him, a compendium of careful attention to the nuances and the lilt of a place. (Originally from Asheville, Williams, who died in 2008, attended Black Mountain College in the 1950s and lived in Scaly Mountain, N.C., for much of his life.) With Richard Owen, the Hillsborough-based poet Jeffery Beam coedited Jonathan Williams: The Lord of Orchards, a new anthology of "essays, images, and shouts" in response to Williams's fifty-plus years of poetry, photography, Southern folk-art collecting, and publishing (he ran famed independent press The Jargon Society). Fittingly, Beam and Owen bring together a cadre of interdisciplinary artists and writers to celebrate the collection. -

Borderlines of Poetry and Art: Vancouver, American Modernism, and the Formation of the West Coast Avant-Garde, 1961 -69

BORDERLINES OF POETRY AND ART: VANCOUVER, AMERICAN MODERNISM, AND THE FORMATION OF THE WEST COAST AVANT-GARDE, 1961 -69 by LARA HALINA TOMASZEWSKA B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1994 M.A., Concordia University, 1998 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Fine Arts) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 2007 © Lara Halina Tomaszewska, 2007 i ABSTRACT In 1967, San Francisco poet Robin Blaser titled his Vancouver-based journal The Pacific Nation because the imaginary nation that he envisaged was the "west coast." Blaser was articulating the mythic space that he and his colleagues imagined they inhabited at Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia: a nation without borders, without nationality, and bound by the culture of poetry. The poetic practices of the San Francisco Renaissance, including beat, projective, and Black Mountain poetics, had taken hold in Vancouver in 1961 with poet Robert Duncan's visit to the city which had catalyzed the Tish poetry movement. In 1963, Charles Olson, Allen Ginsberg, and Robert Creeley participated in the Vancouver Poetry Conference, an event that marked the seriousness and vitality of the poetic avant-garde in Vancouver. The dominant narrative of avant-garde visual art in Vancouver dates its origins to the late 1960s, with the arrival of conceptualism, especially the ideas and work of Dan Graham and Robert Smithson. By contrast, this thesis argues for an earlier formation of the avant-garde, starting with the Tish poetry movement and continuing with a series of significant local events such as the annual Festival of the Contemporary Arts (1961-71), organized by B.C. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Charles Olson, who was born in 1910, did not publish his first poems until 1946, several years after what would prove to be the middle of his life. Indeed, from all the known evidence, he did not even begin writing poems until twenty-nine years old. Before then his overriding ambition had been to be a Melville scholar, a man of letters, a "writer. " Even in college he published only newspaper editorials, book reviews, and a single play. What prompted him to try his hand at poetry? Most likely, as with many poets, it was a gradual awakening, an evolution, rather than an incident along the road to Damascus or a Caedmonic dream. One can be sure it was not encouragement from his early mentor, Edward Dahlberg, who had such an antipathy to modern poetry. Nor was it a directive from Ezra Pound, whom Olson began visiting in 1946, for he had already written many of the poems in the early pages of this edition. We may never know for certain. All he ever said was that it was overhearing the talk of Gloucester fishermen as a boy, on summer evenings, that made him a poet. It never even occurred to me to ask. He just seemed so completely and classically a poet, filling out the role as he did any space or company with his physical and imaginative presence. There was—and is—hardly room for thought of him otherwise. There is, therefore, no section ofjuvenilia in this collection, although some of the earliest poems in their apparent simplicity are those of a beginner.