Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Literary Firsts & Poetry Rare Books

ALEXANDER LITERARY FIRSTS & POETRY RARE BOOKS CATALOGUE TWENTY- SEVEN 2 Alexander Rare Books [email protected]/ (802) 476‐0838 ALEXANDER RARE BOOKS – LITERARY FIRSTS & POETRY Mark Alexander 234 Camp Street Barre, VT 05641 (802) 476-0838 [email protected] Catalogue Twenty–Seven: All items are US, CN or UK Hardcover First Editions & First Printings unless otherwise stated. All items guaranteed & are refundable for any reason within 30 days. Subject to prior sale. VT residents please add 6% sales tax. Checks, Money Orders, Paypal & most credit cards accepted. Net 30 days. Libraries & institutions billed according to need. Reciprocal terms offered to the trade. SHIPPING IS FREE IN THE US (generally Priority Mail) & CANADA, elsewhere $13 per shipment. Visit AlexanderRareBooks.com for cover scans and photos of most catalogued items. I encourage you to visit my website for the latest acquisitions. The best items usually appear on my website, then appear in my catalogues, before appearing elsewhere online. I am always interested in acquiring first editions, single copies or collections, and particularly modernist & contemporary poetry. Thank you in advance for perusing this catalogue. CATALOGUE TWENTY-SEVEN 1) Adam, Helen. THE BELLS OF DIS. West Branch, Iowa: Coffee House Press, 1985. Tall sewn illustrated wraps. Morning Coffee Chapbook: 12. One of 500 copies, numbered and signed by the poet and the artist Ann Mikolowski. A lovely book hand set and hand sewn. Bottom tips bumped, else fine. (10690) $20.00 2) Armantraut, Rae. CONCENTRATE. Green River, VT: Longhouse, 2007. Small (3 x 4 1/2 in.) accordion style chapbook attached to unprinted card covers, with wrap around band. -

BTC Catalog 172.Pdf

Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. ~ Catalog 172 ~ First Books & Before 112 Nicholson Rd., Gloucester City NJ 08030 ~ (856) 456-8008 ~ [email protected] Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Artwork by Tom Bloom. © 2011 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. www.betweenthecovers.com After 171 catalogs, we’ve finally gotten around to a staple of the same). This is not one of them, nor does it pretend to be. bookselling industry, the “First Books” catalog. But we decided to give Rather, it is an assemblage of current inventory with an eye toward it a new twist... examining the question, “Where does an author’s career begin?” In the The collecting sub-genre of authors’ first books, a time-honored following pages we have tried to juxtapose first books with more obscure tradition, is complicated by taxonomic problems – what constitutes an (and usually very inexpensive), pre-first book material. -

Throughout His Writing Career, Nelson Algren Was Fascinated by Criminality

RAGGED FIGURES: THE LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN NELSON ALGREN AND RALPH ELLISON by Nathaniel F. Mills A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney For graduate students on the left ii Acknowledgements Indebtedness is the overriding condition of scholarly production and my case is no exception. I‘d like to thank first John Callahan, Donn Zaretsky, and The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for permission to quote from Ralph Ellison‘s archival material, and Donadio and Olson, Inc. for permission to quote from Nelson Algren‘s archive. Alan Wald‘s enthusiasm for the study of the American left made this project possible, and I have been guided at all turns by his knowledge of this area and his unlimited support for scholars trying, in their writing and in their professional lives, to negotiate scholarship with political commitment. Since my first semester in the Ph.D. program at Michigan, Marjorie Levinson has shaped my thinking about critical theory, Marxism, literature, and the basic protocols of literary criticism while providing me with the conceptual resources to develop my own academic identity. To Patricia Yaeger I owe above all the lesson that one can (and should) be conceptually rigorous without being opaque, and that the construction of one‘s sentences can complement the content of those sentences in productive ways. I see her own characteristic synthesis of stylistic and conceptual fluidity as a benchmark of criticism and theory and as inspiring example of conceptual creativity. -

Of Poets Museletter

Frank Moulton Wisconsin Fellowship founded 1950 Of Poets President MuseletterVice-President Secretary Treasurer Membership Chair Peter Sherrill Cathryn Cofell Roberta Fabiani D.B. Appleton Karla Huston 8605 County Road D 736 W. Prospect Avenue 407 Dale Drive 720 E. Gorham St. #402 1830 W. Glendale Ave. Forestville, WI 54213 Appleton, WI 54914 Burlington, WI 53105 Madison, WI 53703 Appleton, WI 54914 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Summer 2003 www.wfop.org Editor: Christine Falk President’s Message First, thanks to the Mid-Central conference committee for such a wonderful Spring Conference: regional vice-president Joan Johannes and committee members Jeffrey Johannes, Lucy Rose Johns, Casey Martin, Grace Bushman, Barbara Cranford, Mary Lou Judy, Linda Aschbrenner, Phil Hansotia, Kris Rued- Welcome to the following new Clark, Gloria Federwitz, and Bruce Dethlefsen. The organization was excellent, members of the Wisconsin Fellowship the hotel first-rate (and a very respectable room rate, at that!) And the program of Poets that have joined since the inspiring. Spring Museletter issue: In addition to the traditional Friday-night Open Mic, and the Saturday Roll Call Poems, presenters Bill Weise and James Lee livened up the afternoon. Bill Weise Kristin Alberts Brussels blended music, drumming and audience participation in his demonstration on Edward DiMaio Egg Harbor using the spiritual energy inside us to open new creative possibilities. James Lee, Earle Garber Wisconsin Rapids Daniel Greene Smith Madison award-winning Madison poet, recited from his own high-energy works and used Kathleen Grieger Menomonee Falls audience-generated images in a spontaneous performance poem at the end of his Lincoln Hartford New Lisbon presentation. -

Peter Anastas Papers

PETER ANASTAS PAPERS Creator: Peter Nicholas Anastas Dates: 1954-2017 Quantity: 26.0 linear feet (26 document boxes) Acquisition: Accession #: 2014.077 ; Donated by: Peter Anastas Identification: A77 ; Archive Collection #77 Citation: [Document Title]. The Peter Anastas Papers, [Box #, Folder #, Item #], Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Peter Anastas Biographical Note Peter Nicholas Anastas, Jr. was born in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1937. He attended local schools, graduating in 1955 from Gloucester High School, where he edited the school newspaper and was president of the National Honor Society. His father Panos Anastas, a restaurateur, was born in Sparta, Greece in 1899, and his mother, Catherine Polisson, was born in Gloucester of native Greek parents, in 1910. His brother, Thomas Jon “Tom” Anastas, a jazz musician, arranger and composer, was born in Gloucester, in 1939, and died in Boston, in 1977. Anastas attended Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, on scholarship, majoring in English and minoring in Italian, philosophy and classics. While at Bowdoin, he wrote for the student Peter Anastas Papers – A77 – page 2 newspaper, the Bowdoin Orient, and was editor of the college literary magazine, the Quill. In 1958, he was named Bertram Louis, Jr. Prize Scholar in English Literature, and in 1959 he was awarded first and second prizes in the Brown Extemporaneous Essay Contest and selected as a commencement speaker (his address was on “The Artist in the Modern World.”) During his summers in college, Anastas edited the Cape Ann Summer Sun, published by the Gloucester Daily Times, and worked on the waterfront in Gloucester. -

Mcdowell Title Page

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mf693nb Author McDowell, Tara Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 By Tara Cooke McDowell A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus T.J. Clark Professor Emerita Kaja Silverman Spring 2013 Abstract House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 by Tara McDowell Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair This dissertation examines the work of the San Francisco-based artist Jess (1923-2004). Jess’s multimedia and cross-disciplinary practice, which takes the form of collage, assemblage, drawing, painting, film, illustration, and poetry, offers a perspective from which to consider a matrix of issues integral to the American postwar period. These include domestic space and labor; alternative family structures; myth, rationalism, and excess; and the salvage and use of images in the atomic age. The dissertation has a second protagonist, Robert Duncan (1919-1988), preeminent American poet and Jess’s partner and primary interlocutor for nearly forty years. Duncan and Jess built a household and a world together that transgressed boundaries between poetry and painting, past and present, and acknowledged the limits and possibilities of living and making daily. -

Uconn Libraries Newsletter Volume 18 Number 1

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn UConn Libraries Newsletter UConn Library Spring 2012 UConn Libraries Newsletter Volume 18 Number 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/libr_news Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation "UConn Libraries Newsletter Volume 18 Number 1" (2012). UConn Libraries Newsletter. 48. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/libr_news/48 UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT YourLIBRARIES Information CONNection www.lib.uconn.edu Spring 2012 Historical Aerial Photos of Connecticut’s Coast Now Online Result of MAGIC and DEEP Collaboration In August 2011, Tropical Storm Irene coast, major waterways, and natural resources Long Island Sound Programs (OLISP) of took a hard swipe at Connecticut’s are much easier to understand now that his- the Connecticut Department of Energy and 350 miles of coastline, eroding dunes torical aerial photographs of the state’s coast Environmental Protection (DEEP). and redistributing sand to the extent covering the past 40 years are available online. Since 1974, OLISP has conducted aerial that the state’s coastline appeared to The new resource is the result of collaboration surveys of the state’s coastline approxi- be altered. The consequences of such between UConn Libraries Map and Geographic major weather events on Connecticut’s taken in color infrared, a format that pres- mately every five years. The photos are ents vegetation as shades of red and water Information Center (MAGIC) and the Office of in black, making it easier to identify natural Aerial views of Griswold resources and the demarcation between Point, Old Lyme, CT, water and land. They are widely used for a barrier beach at the site reviews and assessments that sup- mouth of the Connecticut port permitting and planning activities, to River, taken more than 25 years apart, are now 1974 2000 available online. -

Special Topics Course Descriptions

Anth 180A: The Anthropology of Childhood Ann Metcalf M, W 11:00-12:15 Fall 2015 “It seemed clear to me that a culture that repudiated children could not be a good culture…” Margaret Mead How do children grow, learn, respond to and shape their worlds? Is childhood a universally recognized stage of human development? Is it a time of innocence or agency? What cultural forces shape and influence children, and in what ways are children initiators of cultural change? This course will explore childhood from a cross-cultural, anthropological perspective. We will begin with a focus on traditional and tribal cultures, exploring parenting and child rearing, language acquisition, play, work, sexuality, and transition to adulthood. Then we will consider issues arising from industrialization, colonization and globalization: gender, race and class, child labor, sex trafficking, education, the effects of war and famine, the emergence of children’s rights movements. Selected Readings Why Don’t Anthropologists Like Children? Lawrence A Hirschfeld The Ethnography of Childhood, Margaret Mead Childhood in the Trobriand Islands, Bronislaw Malinowski Infant Care in the Kalahari Desert, Melvin Konner Swaddling, Cradleboarding and the Development of Children, James Chisholm Child’s Play in Italian Perspective, Rebecca New Talking to Children in Western Samoa, Elinor Ochs Altruistic and Egoistic Behavior of Children in Six Cultures, John Whiting and Beatrice Whiting Why African Children Are So Hard to Test, Sue Harkness and Charles Super Getting in, Dropping Out, and Staying on: Determinants of Girls’ School Attendance in the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal, Sarah LeVine The Child as Laborer and Consumer: the Disappearance of Childhood in Contemporary Japan, Norma Field Seducing the Innocent: Childhood and Television in Postwar America, Lynn Spigel . -

On Michael Rumaker

IAN BRINTON | PB Breaking Out I Ian Brinton When Michael Rumaker was kicked out of his home in Gloucester County, south of the Delaware River, in 1950 it was an expulsion directed by his father and with his mother’s tacit assent. It was for not going to church and for being queer. A year later he heard Ben Shahn give a lecture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art extolling the virtues of the unconventional and innovative educational establishment in the western hills of North Carolina: Black Mountain College. Arriving on a work scholarship in 1952 he later recorded his initial reactions: The place was in many ways just as I had envisioned it: steep mountains with isolated buildings along the slopes, a sense of vast wilderness-like space and isolation. Soon picking up on the unusual sense of educational space being provided he “also recognized, with a delicious excitement of my well-hidden but naturally rebellious heart, that there was something going on in this isolated backwoods called Black Mountain College that I had never conceived of in the world outside.” Going on to describe how he learned his first lesson at Black Mountain he 126 | GOLDEN HANDCUFFS REVIEW IAN BRINTON | PB remembered “When confronted with objects of creation beyond my comprehension to keep my mouth firmly shut and my eyes and ears open.” The latter part of that observation he kept firmly to throughout his writing career. Travelling into Ashville with Charles and Connie Olson on the first Friday night after starting he felt that “maybe here I could finally learn to -

2019 Annual Report

2019 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Friends, This has been another year of unparalleled exhibitions and performances, a celebration of what’s possible in our new home and with the support of our community. At the beginning of 2019, we were in the last few weeks of the inaugural exhibition at 120 College Street, Between Form and Content: Perspectives on Jacob Lawrence and Black Mountain College, which was a major accomplishment in its scope and its expansion of community partnerships. Next, we presented an intimate look at the school’s political dimensions, both internal and external, through the exhibition Politics at Black Mountain College. During the same time period, the exhibition Aaron Siskind: A Painter’s Photographer and Works on Paper by BMC Artists revealed the photographer’s elegant approach to abstraction alongside works by others in his circle of influence. From June through August, our galleries filled with sound as part of Materials, Sounds + Black Mountain College, an exploration of contemporary experimental and material-based processes rooted in theories and practices developed at Black Mountain College. We closed out the year with VanDerBeek + VanDerBeek, an exhibition that bridges the historic and contemporary through an intergenerational artistic conversation. 2019 also marked the 100th birthday of Merce Cunningham, and 100 years since the founding of the Bauhaus, which closed in the same year Black Mountain College opened, seeding the latter with its faculty and utopian values. Both centennials sparked global celebrations, transcending geographic and disciplinary boundaries to honor the impact of courageous communities and collaborators. Image credit: Come Hear NC (NCDNCR) | Ken Fitch We joined the world in these celebrations through a special installation of historic dance films of the Cunningham Dance Company at this year’s {Re}HAPPENING, the exhibition BAUHAUS 100, and a virtual reality exploration of the Bauhaus Dessau building, on loan from the Goethe- Institut. -

William Bronk

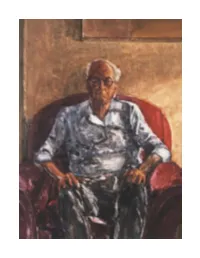

Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk David Clippinger Argotist Ebooks 2 * Cover image by Daniel Leary Copyright © David Clippinger 2012 All rights reserved Argotist Ebooks * Bill in a Red Chair, monotype, 20” x 16” © Daniel Leary 1997 3 The surest, and often the only, way by which a crowd can preserve itself lies in the existence of a second crowd to which it is related. Whether the two crowds confront each other as rivals in a game, or as a serious threat to each other, the sight, or simply the powerful image of the second crowd, prevents the disintegration of the first. As long as all eyes are turned in the direction of the eyes opposite, knee will stand locked by knee; as long as all ears are listening for the expected shout from the other side, arms will move to a common rhythm. (Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power) 4 Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk 5 Part I “So Large in His Singleness” By 1960 William Bronk had published a collection, Light and Dark (1956), and his poems had appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, Origin, and Black Mountain Review. More, Bronk had earned the admiration of George Oppen and Charles Olson, as well as Cid Corman, editor of Origin, James Weil, editor of Elizabeth Press, and Robert Creeley. But given the rendering of the late 1950s and early 1960s poetry scene as crystallized by literary history, Bronk seems to be wholly absent—a veritable lacuna in the annals of poetry. -

Ac Know Ledg Ments

A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s In the course of my research, Robert Duncan’s friends, without exception, granted me a share in the generosity, goodwill, and love for life that so char- acterized his being. Two people made a special eff ort to help me understand Robert Duncan’s “dailiness,” and their insights were key factors in the making of this book. Jess Collins agreed that it was an appropriate time for a biography of Duncan to be written, and he welcomed me into his life for a little bit over a de cade, allowing me to experience the rituals of house hold that he had shared with Duncan. Barbara Jones and her family in Bakersfi eld, California, extended me great hospitality. Barbara’s memories of her brother as a child and of their life in the San Joaquin Valley were in all ways illuminating. Th eir insights were key factors in the making of this book. Th is book was also made possible through the ongoing tireless support of my husband, Th omas Evans. His own studies of Jess, Duncan, and the West Coast assemblage artists contributed at every turn to the thoroughness of this book. His companionship allows me to live in a house hold as rich as Jess and Duncan’s. I am grateful to Robert Duncan’s friends, family, students and acquaintances: Gerald Ackerman, Robert Adamson, the late Virginia Admiral, Charles Alexander, the late Donald Allen, Michael Anania, Bruce Andrews, Norman Austin, Todd Baron, Dawn Michelle Baude, Tosh Berman, Charles Bern- stein, Robert Bertholf, the late Robin Blaser, Richard Blevins, George Bower- ing, the late Stan Brakhage, the late David Bromige, the late James Brough- ton, the late Norman O.