Contemporary French Poetry, Intermedia, and Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2005 Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism Glenn W. Fetzer Calvin College Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Fetzer, Glenn W. (2005) "Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1591 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jean-Marie Gleize, Emmanuel Hocquard, and the Challenge of Lyricism Abstract Within the past decade, one of the most pressing questions of poetry in France has been the continuing viability of lyricism. Recent models of perceiving the nature of lyricism shift the focus from formal and thematic considerations to pragmatic ones. As Hocquard's Un test de solitude: sonnets (1998) and Gleize's Non (1999) illustrate, the challenge of the lyric today serves to sharpen the sense of alterity and gives evidence of lyricism's capacity for renewal. More specifically, in presenting a reading of sonnets from both writers, this paper shows that the debates on the nature and "recurrence" of lyricism foreground the relational mode, above all, and give witness to the capacity of the lyric to withstand, to test, and ultimately, to reinvent itself. -

Emmanuel Hocquard, Late Additions

Emmanuel Hocquard LATE ADDITIONS SERlE D'ECRITURE NO. TWO Serie d'ecriture no. 1: Alain Veinstein, Archeology of the Mother, 1986 Serie d'ecriture no. 2: Emmanuel Hocquard: Late Additions, 1988 Serie d'ecriture no. 3: magazine issue, forthcoming Serie d'ecriture is an irregularly produced journal given to English translations of current French writing. Issues given to the work of a single author will alternate with magazine issues. The journal is edited by Rosmarie Waldrop and pub lished, with the collaboration of Burning Deck, by: SPECTACULAR DISEASES c/o Paul Green 83 (b) London Road Peterborough, Cambs., PE2 9BS United Kingdom Individual copies are priced at Ll.SO, with subscriptions available at L2.00 for two issues. Postage should be added at 25p per copy in all instances. US price $3.50, with sub scriptions at $4.50 plus $2 postage for 2 issues. Distributed in the US by: Segue Distribution, 300 Bowery, New York, NY 10012 Small Press Distribution, 1814 San Pablo Ave., Berkeley, CA 94702 ISSN 0269 - 0179 Copyright (c) 1988 by Emmanuel Hocquard, Connell lV1cGrath and Rosmarie Waldrop Some of the translations in this issue were first printed in Acts, 0- blek and Verse. The editor and publisher regret the omission of credit for the cover of issue no.l, a montage by the Australian artist Denis Mizzi. The cover of this issue is by Raquel. SERlE D'ECRITURE No. 2: Emmanuel Hocquard LATE ADDITIONS translated from the French by Rosmarie Waldrop and Connell McGrath SPECTACULAR DISEASES 1988 24 November and the words: shadow of the last tree. -

Chicago Chicago Fall 2015

UNIV ERSIT Y O F CH ICAGO PRESS 1427 EAST 60TH STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60637 KS OO B LL FA CHICAGO 2015 CHICAGO FALL 2015 FALL Recently Published Fall 2015 Contents General Interest 1 Special Interest 50 Paperbacks 118 Blood Runs Green Invisible Distributed Books 145 The Murder That Transfixed Gilded The Dangerous Allure of the Unseen Age Chicago Philip Ball Gillian O’Brien ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23889-0 Author Index 412 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24895-0 Cloth $27.50/£19.50 Cloth $25.00/£17.50 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23892-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24900-1 COBE/EU Title Index 414 Subject Index 416 Ordering Inside Information back cover Infested Elephant Don How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse Bedrooms and Took Over the World Caitlin O’Connell Brooke Borel ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10611-3 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04193-3 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10625-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04209-1 Plankton Say No to the Devil Cover illustration: Lauren Nassef Wonders of the Drifting World The Life and Musical Genius of Cover design by Mary Shanahan Christian Sardet Rev. Gary Davis Catalog design by Alice Reimann and Mary Shanahan ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18871-3 Ian Zack Cloth $45.00/£31.50 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23410-6 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-26534-6 Cloth $30.00/£21.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23424-3 JESSA CRISPIN The Dead Ladies Project Exiles, Expats, and Ex-Countries hen Jessa Crispin was thirty, she burned her settled Chica- go life to the ground and took off for Berlin with a pair of W suitcases and no plan beyond leaving. -

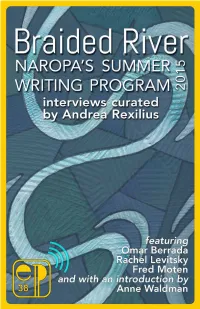

Rexilluslt Spreads1 .Pdf

BRAIDED RIVER interviews curated by ANDREA REXILIUS #38 ESSAY PRESS LISTENING TOUR As the Essay Press website re-launches, we have commissioned some of our favorite conveners of public discussions to curate conversation-based CONTENTS chapbooks. Overhearing such dialogues among poets, prose writers, critics and artists, we hope to re-envision how Essay can emulate and expand upon recent developments in trans-disciplinary small-press culture. Introduction v by Anne Waldman Series Editors Maria Anderson Interview with Rachel Levitsky 1 Andy Fitch Interview with Fred Moten 20 Ellen Fogelman Aimee Harrison Interview with Omar Berrada 24 Courtney Mandryk Afterword 46 Victoria A. Sanz by Andrea Rexilius Travis Sharp Acknowledgments 50 Ryan Spooner Randall Tyrone About Naropa 2016 51 Author Bios 52 Series Assistants Cristiana Baik Ryan Ikeda Christopher Liek Cover Image Courtesy of Jane Dalrymple-Hollo Cover Design Courtney Mandryk Layout Aimee Harrison INTRODUCTION — Anne Waldman SWP Artistic Directior hese are three interviews, the same questions Tfor three eminent, wildly progressive poets who have been guest faculty during Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics Summer Writing Program—all visiting/teaching/performing at Naropa before these conversations took place, but queried here specifically in the context of our 2015 pedagogy, which carried the themic rubric of Braided River, the Activist Rhizome. Symbiosis (= “together living”) teaches that life is more like a braided river, horizontal waterflow with tributaries falling apart and coming together again (as algae, as fungi do), rather than the Abrahamic tree of life with its vertical, hierarchical branch system. We are the riparians alongside, inside, riding this river of inter- connectivity. -

The War Against Pre-Terrorism the Tarnac 9 and the Coming Insurrection

COMMENTARY The war against pre-terrorism The Tarnac 9 and The Coming Insurrection Alberto Toscano n 11 November 2008, twenty youths were arrested in Paris, Rouen and the village of Tarnac, in the Massif Central district of Corrèze. The Tarnac Ooperation involved helicopters, 150 balaclava-clad anti-terrorist policemen, with studiously prearranged media coverage. The youths were accused of having participated in a number of sabotage attacks against high-speed TGV train routes, involving the obstruction of the trains’ power cables with horseshoe-shaped iron bars, causing a series of delays affecting some 160 trains. The suspects who remain in custody were soon termed the ‘Tarnac Nine’, after the village where some of them had purchased a small farmhouse, reorganized the local grocery store as a cooperative, and taken up a number of civic activities from the running of a film club to the delivery of food to the elderly. The case The minister of the interior, Michèle Alliot-Marie, promptly intervened to underline the presumption of guilt and to classify the whole affair under the rubric of terrorism, linking it to the supposed rise of an insurrectionist ‘ultra-Left’, or ‘anarcho-autonomist tendency’. The nine were interrogated and detained for ninety-six hours. Four were subsequently released. The official accusation was ‘association of wrongdoers in relation to a terrorist undertaking’, a charge that can carry up to twenty years in jail. On 2 December, three more of the Tarnac Nine were released under judiciary control, leaving two in jail, at the time of writing (early January 2009): Julien Coupat and Yldune Lévy. -

Tarnac, General Store | Issue 16 | N+1

Tarnac, General Store | Issue 16 | n+1 https://nplusonemag.com/issue-16/translation/tarnac-general-store/ 1 of 26 7/3/15, 4:54 PM Tarnac, General Store | Issue 16 | n+1 https://nplusonemag.com/issue-16/translation/tarnac-general-store/ Translation DAVID DUFRESNE, NAMARA SMITH Tarnac, General Store Anarchist farmers vs. Inspector Clouseau Published in: Issue 16: Double Bind Publication date: Spring 2013 2 of 26 7/3/15, 4:54 PM Tarnac, General Store | Issue 16 | n+1 https://nplusonemag.com/issue-16/translation/tarnac-general-store/ The road to Tarnac, Tarnac, France, 2011. Courtesy of David Dufresne. In the spring of 2007, a small left-wing press in Paris published a book called The Coming Insurrection. Its anonymous authors, who went by the name the Invisible Committee, argued that the riots that had spread through France’s immigrant banlieues a year earlier signaled an impending wave of antistate action. The new form of protest imagined by the Invisible Committee would make no demands and have no hierarchical organization. Rather, the coming movement would be built around independent, self-sustaining communes and the sabotage of centralized infrastructure. Two months after The Coming Insurrection was published, Nicolas Sarkozy won the French presidential election on a promise to “liquidate once and for all” the antiauthoritarian legacy of the 1968 student movement. The identity of the Invisible Committee soon became a subject of official concern. The French intelligence service linked The Coming Insurrection’s literary fingerprints—a highly specific theoretical framework and elegant style—to a former graduate student named Julien Coupat, who had ended his studies in intellectual history to edit the short-lived journal Tiqqun (1999–2001). -

Bye-Bye St. Eloi! Observations Concerning the Definitive Indictment Issued by the Public Prosecutor Of

Bye-Bye St. Eloi! Observations Concerning the Definitive Indictment Issued by the Public Prosecutor of the Republic in the So-called Tarnac Affair1 Addressed to Mme Jeanne Duyé, Examining Magistrate 4 Boulevard du Palais 75001 Paris 8 June 2015 Written by Christophe Becker, Mathieu Burnel, Julien Coupat, Bertrand Deveaud, Manon Glibert, Gabrielle Hallez, Elsa Hauck, Yildune Lévy, Benjamin Rosoux and Aria Thomas2 1 Translated by NOT BORED! 20 July 2015. An italicized phrase in brackets [like this] is the original French; a phrase in brackets without italics [like this] has been added by the translator. All footnotes by the translator. Please note that we have reproduced the image of Saint Eloi, aka St. Eligius (patron saint of goldsmiths), which, without any caption or explanation, accompanied the original French text. It certainly puns on la galerie St. Eloi, which is the name of the headquarters of the French counter-terrorist judiciary, located within the Palais du Justice. 2 Aka the “Tarnac 10.” 2 “They wanted to play a much more important and direct role in the tracking down and neutralization of the leader of Al-Qaeda. To demonstrate their abilities, they elaborated an extremely audacious plan to seize Osama bin Laden at the home of one of his wives, located on an isolated farm in the Tarnak region, at the edge of the Registan desert. (…) Satellite photos showed that many Al-Qaeda dignitaries chose to live at the farm in question, in Tarnak, with [their] wives and children.” – Roland Jacquard and Atmane Tazaghart, La destruction programmée de l'Occident3 “Thus the judgment of such a detestable crime must be extraordinarily well-calculated [traicté] and different from the other ones. -

La Communication Dans Les Établissements D'enseignement

2015 / 16 LIVRE BLANC LA COMMUNICATION DANS LES ÉTABLISSEMENTS d’enseignement GRANDES ÉCOLES ET UNIVERSITÉS SUPÉRIEUR FACE AUX DÉFIS DE LA COMMUNICATION GLOBALE @lalliance_edu @audencia @ConferenceDesGE Frank Dormont @FrankDormont Olivier Rollot @O_Rollot REMERCIEMENTS Pour la réalisation de ce Livre Blanc nous avons interviewé : Andria Andriuzzi, directeur de la communication d’ESCP Europe Alexia Anglade, directrice de la communication de Toulouse BS Dominique Celier, directrice de la communication de Télécom ParisTech Béatrice Chandellier, directrice de la communication interne d’Audencia Group Valérie Chilard, directrice de la communication de Centrale Nantes Sophie Commereuc, présidente de la commission communication de la Conférence des grandes écoles et directrice de l’Ecole nationale supérieure de chimie de Clermont-Ferrand Frank Dormont, directeur de la communication d’Audencia Group et Pilote de la communication de l’alliance Centrale Audencia ensa Nantes Brigitte Fournier, directrice de l’agence de communication NSB – Noir Sur Blanc Mathieu Gabai, président de Quatre Vents Group Maxime Gambini, directeur du développement, du marketing et de la communication du groupe Sup de Co La Rochelle Jérôme Guilbert, directeur de la communication de Sciences Po Paris Claire Laval-Jocteur, directrice de la communication de l’UPMC et présidente de l’Arces Nathalie Le Calvez, directrice de la communication des Mines de Nantes Emilie Lelong-Turcato, directrice adjointe de la communication d’Audencia Group Bernard Lévêque, directeur marketing -

Norma Cole Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8k077nv No online items Norma Cole Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2015 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Norma Cole Papers MSS 0766 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Norma Cole Papers Creator: Cole, Norma Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0766 Physical Description: 36 Linear feet(84 archives boxes, 4 card file boxes, 1 flat box, and 1 map case folder) Date (inclusive): 1940-2014 (bulk 1985-2014) Abstract: Papers of poet, artist and translator Norma Cole. Cole lived and worked in the San Francisco Bay Area and collaborated with American, French and Canadian poets. The collection includes correspondence, manuscripts, notebooks, translations, photographs, negatives, sound and video recordings, digital media, artwork and ephemera. Scope and Content of Collection Papers of poet, artist and translator Norma Cole. Cole lived and worked in the San Francisco Bay Area and collaborated with American, French and Canadian poets. The collection contains correspondence, manuscripts, notebooks, translations, photographs, negatives, sound and video recordings, digital media, artwork and ephemera. Arranged in thirteen series: 1) BIOGRAPHICAL, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS BY COLE, 4) COLLABORATIVE WORKS, 5) WORKS BY OTHERS, 6) TRANSLATIONS, 7) ARTWORK, 8) EPHEMERA, 9) SUBJECT FILES, 10) PHOTOGRAPHS 11) SOUND RECORDINGS, 12) VIDEO RECORDINGS and 13) DIGITAL MEDIA. Biography Poet, translator, visual artist and curator Norma Cole was born in Toronto, Canada on May 12, 1945. -

Agamben: “Terrorism Or Tragicomedy?”

Agamben: “Terrorism or Tragicomedy?” Libération, November 19, 2008 Terrorism or Tragicomedy? Giorgio Agamben On the morning of November 11, 150 police officers, most of which belonged to the anti-terrorist brigades, surrounded a village of 350 inhabitants on the Millevaches plateau, before raiding a farm in order to arrest nine young people (who ran the local grocery store and tried to revive the cultural life of the village). Four days later, these nine people were sent before an anti-terrorist judge and “accused of criminal association with terrorist intentions.” The newspapers reported that the Ministry of the Interior and the Secretary of State “had congratulated local and state police for their diligence.” Everything is in order, or so it would appear. But let’s try to examine the facts a little more closely and grasp the reasons and the results of this “diligence.” First the reasons: the young people under investigation “were tracked by the police because they belonged to the ultra-left and the anarcho autonomous milieu.” As the Ministry of the Interior specifies, “their discourse is very radical and they have links with foreign groups.” But there is more: certain of the suspects “participate regularly in political demonstrations,” and, for example, “in protests against the Fichier Edvige (Exploitation Documentaire et Valorisation de l’Information Générale) and against the intensification of laws restricting immigration.” So political activism (this is the only possible meaning of linguistic monstrosities such as “anarcho autonomous milieu”) or the active exercise of political freedoms, and employing a radical discourse are therefore sufficient reasons to call in the anti-terrorist division of the police (SDAT) and the central intelligence office of the Interior (DCRI). -

1 DISSERTATIONS in PROGRESS Compiled And

DISSERTATIONS IN PROGRESS Compiled and Edited by Madeline Turan, Stony Brook University This is the forty-ninth annual listing of doctoral dissertations from graduate programs in North America. It should be considered a supplement of preceding lists. Defended dissertations are listed as a separate section, after the “Dissertations in Progress” list. The dissertation titles are listed alphabetically under “Cultural Studies,” “Film Studies,” “Linguistics,” “Literature,” or “Pedagogy”. Literature dissertations are arranged by century and author or are listed under “General.” There is also a separate section for Francophone authors and topics. In each entry, the name of the dissertation director and that of the institution are given in parentheses. Titles are numbered consecutively within each section. Title changes are noted at the end of each section, showing the number of the dissertation as it was previously listed, followed by the new title. It should be noted that, in general, the information was compiled as submitted by each institution. We regret that titles from a few schools were not received in time for publication. DISSERTATIONS IN PROGRESS (2012) A. CULTURAL STUDIES 88. Comic Memory: Franco-Algerian Relations through Humor (1954–2012). Sandra Rousseau (Jennifer A. Boittin, Pennsylvania State University) 89. Cuisine and the French Social Imaginary: Tracing the Origins of Gastronomic Discourse in Early-19th-Century France. Maximillian Shrem (Anne Deneys- Tunney, New York University) 90. Designing Women: Fashion and Fiction in Second Empire France. Sara Phenix (Andrea Goulet, University of Pennsylvania) 91. Intellectuel résistant: l’anti-impérialisme contestataire de Claude Bourdet dans l’après-guerre. Fabrice Picon (Jennifer Boittin, Pennsylvania State University) 92. -

Poet-Translators in Nineteenth Century French Literature: Nerval, Baudelaire, Mallarmé” Dir

POET-TRANSLATORS IN NINETEENTH CENTURY FRENCH LITERATURE: NERVAL, BAUDELAIRE, MALLARMÉ by Jena Whitaker A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland April 2018 Ó 2018 Jena Whitaker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The ‘poet-translator is a listener whose ears are transformed through translation. The ear not only relates to the sensorial, but also to the cultural and historical. This dissertation argues that the ‘poet-translator,’ whose ears encounter a foreign tongue discovers three new rhythms: a new linguistic rhythm, a new cultural rhythm, and a new experiential rhythm. The discovery of these different rhythms has a pronounced impact on the poet-translator’s poetics. In this case, poetics does not refer to the work of art, but instead to an activity. It therefore concerns the reader’s will to listen to what a text does and to understand how it works. Although the notion of the ‘poet-translator’ pertains to a wide number of writers, time periods, and fields of study, this dissertation focuses on three nineteenth-century ‘poet-translators’ who each partly as a result of their contact with German romanticism formed an innovative and fresh account of linguistic, cultural, and poetic rhythm: Gérard de Nerval (1808-1855), Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), and Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898). Each of these ‘poet-translators acted as cultural mediators, contributing to the development of new literary genres and new forms of critique that came to have significant effects on Western Literature. A study of Nerval, Baudelaire and Mallarmé as ‘poet-translators’ is historically pertinent for at least four reasons.