Possible Protoasian Archaic Residue and the Statigraphy of Diffusional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fi~Eeting Encounter with the Moken Cthe Sea Gypsies) in Southern Thailand: Some Linguistic and General Notes

A FI~EETING ENCOUNTER WITH THE MOKEN CTHE SEA GYPSIES) IN SOUTHERN THAILAND: SOME LINGUISTIC AND GENERAL NOTES by Christopher Court During a short trip (3-5 April 1970) to the islands of King Amphoe Khuraburi (formerly Koh Kho Khao) in Phang-nga Province in Southern Thailand, my curiosity was aroused by frequent references in conversation with local inhabitants to a group of very primitive people (they were likened to the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves) whose entire life was spent nomadically on small boats. It was obvious that this must be the Moken described by White ( 1922) and Bernatzik (1939, and Bernatzik and Bernatzik 1958: 13-60). By a stroke of good fortune a boat belonging to this group happened to come into the beach at Ban Pak Chok on the island of Koh Phrah Thong, where I was spending the afternoon. When I went to inspect the craft and its occupants it turned out that there were only women and children on board, the one man among the occupants having gone ashore on some errand. The women were extremely shy. Because of this, and the failing light, and the fact that I was short of film, I took only two photographs, and then left the people in peace. Later, when the man returned, I interviewed him briefly elsewhere (see f. n. 2) collecting a few items of vocabulary. From this interview and from conversations with the local residents, particularly Mr. Prapa Inphanthang, a trader who has many dealings with the Moken, I pieced together something of the life and language of these people. -

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

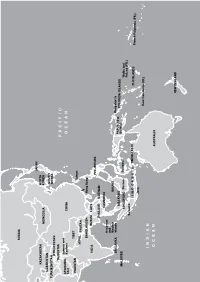

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

The Malayic-Speaking Orang Laut Dialects and Directions for Research

KARLWacana ANDERBECK Vol. 14 No., The 2 Malayic-speaking(October 2012): 265–312Orang Laut 265 The Malayic-speaking Orang Laut Dialects and directions for research KARL ANDERBECK Abstract Southeast Asia is home to many distinct groups of sea nomads, some of which are known collectively as Orang (Suku) Laut. Those located between Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula are all Malayic-speaking. Information about their speech is paltry and scattered; while starting points are provided in publications such as Skeat and Blagden (1906), Kähler (1946a, b, 1960), Sopher (1977: 178–180), Kadir et al. (1986), Stokhof (1987), and Collins (1988, 1995), a comprehensive account and description of Malayic Sea Tribe lects has not been provided to date. This study brings together disparate sources, including a bit of original research, to sketch a unified linguistic picture and point the way for further investigation. While much is still unknown, this paper demonstrates relationships within and between individual Sea Tribe varieties and neighbouring canonical Malay lects. It is proposed that Sea Tribe lects can be assigned to four groupings: Kedah, Riau Islands, Duano, and Sekak. Keywords Malay, Malayic, Orang Laut, Suku Laut, Sea Tribes, sea nomads, dialectology, historical linguistics, language vitality, endangerment, Skeat and Blagden, Holle. 1 Introduction Sometime in the tenth century AD, a pair of ships follows the monsoons to the southeast coast of Sumatra. Their desire: to trade for its famed aromatic resins and gold. Threading their way through the numerous straits, the ships’ path is a dangerous one, filled with rocky shoals and lurking raiders. Only one vessel reaches its destination. -

'Undergoer Voice in Borneo: Penan, Punan, Kenyah and Kayan

Undergoer Voice in Borneo Penan, Punan, Kenyah and Kayan languages Antonia SORIENTE University of Naples “L’Orientale” Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology-Jakarta This paper describes the morphosyntactic characteristics of a few languages in Borneo, which belong to the North Borneo phylum. It is a typological sketch of how these languages express undergoer voice. It is based on data from Penan Benalui, Punan Tubu’, Punan Malinau in East Kalimantan Province, and from two Kenyah languages as well as secondary source data from Kayanic languages in East Kalimantan and in Sawarak (Malaysia). Another aim of this paper is to explore how the morphosyntactic features of North Borneo languages might shed light on the linguistic subgrouping of Borneo’s heterogeneous hunter-gatherer groups, broadly referred to as ‘Penan’ in Sarawak and ‘Punan’ in Kalimantan. 1. The North Borneo languages The island of Borneo is home to a great variety of languages and language groups. One of the main groups is the North Borneo phylum that is part of a still larger Greater North Borneo (GNB) subgroup (Blust 2010) that includes all languages of Borneo except the Barito languages of southeast Kalimantan (and Malagasy) (see Table 1). According to Blust (2010), this subgroup includes, in addition to Bornean languages, various languages outside Borneo, namely, Malayo-Chamic, Moken, Rejang, and Sundanese. The languages of this study belong to different subgroups within the North Borneo phylum. They include the North Sarawakan subgroup with (1) languages that are spoken by hunter-gatherers (Penan Benalui (a Western Penan dialect), Punan Tubu’, and Punan Malinau), and (2) languages that are spoken by agriculturalists, that is Òma Lóngh and Lebu’ Kulit Kenyah (belonging respectively to the Upper Pujungan and Wahau Kenyah subgroups in Ethnologue 2009) as well as the Kayan languages Uma’ Pu (Baram Kayan), Busang, Hwang Tring and Long Gleaat (Kayan Bahau). -

The Sea Within: Marine Tenure and Cosmopolitical Debates

THE SEA WITHIN MARINE TENURE AND COSMOPOLITICAL DEBATES Hélène Artaud and Alexandre Surrallés editors IWGIA THE SEA WITHIN MARINE TENURE AND COSMOPOLITICAL DEBATES Copyright: the authors Typesetting: Jorge Monrás Editorial Production: Alejandro Parellada HURIDOCS CIP DATA Title: The sea within – Marine tenure and cosmopolitical debates Edited by: Hélène Artaud and Alexandre Surrallés Print: Tarea Asociación Gráfica Educativa - Peru Pages: 226 ISBN: Language: English Index: 1. Indigenous Peoples – 2. Maritime Rights Geografical area: world Editorial: IWGIA Publications date: April 2017 INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmak Tel: (+45) 35 27 05 00 – E-mail: [email protected] – Web: www.iwgia.org To Pedro García Hierro, in memoriam Acknowledgements The editors of this book would like to thank the authors for their rigour, ef- fectiveness and interest in our proposal. Also, Alejandro Parellada of IWGIA for the enthusiasm he has shown for our project. And finally, our thanks to the Fondation de France for allowing us, through the “Quels littoraux pour demain? [What coastlines for tomorrow?] programme to bring to fruition the reflection which is the subject of this book. Content From the Land to the Sea within – A presentation Alexandre Surrallés................................................................................................ .. 11 Introduction Hélène Artaud...................................................................................................... ....15 PART I -

1.2 the Urak Lawoi

'%/!4,!3¸ 7/2,$ 6%#4/2 '2!0() /'2%¸ &RANCE - !9!.-! 2 Other titles in the CSI series 20 Communities in Action: Sharing the experiences. Report on ‘Mauritius ,!/ 3 Coastal region and small island papers: Strategy Implementation: Small Islands Voice Planning Meeting’, Bequia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, 11-16 July 2005. 50 pp. (English only). 1 Managing Beach Resources in the Smaller Caribbean Islands. Workshop Available electronically only at: www.unesco.org/csi/smis/siv/inter-reg/ Papers. Edited by Gillian Cambers. 1997. 269 pp. (English only). SIVplanmeet-svg3.htm www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers/papers1.htm 21 Exit from the Labyrinth. Integrated Coastal Management in the 2 Coasts of Haiti. Resource Assessment and Management Needs. 1998. Kandalaksha District, Murmansk Region of the Russian Federation. 2006. 75 39 pp. (English and French). pp. (English). www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers4/lab.htm www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers/papers2.htm www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers/papiers2.htm 3 CARICOMP – Caribbean Coral Reef, Seagrass and Mangrove Sites. Titles in the CSI info series: Edited by Björn Kjerfve. 1999. 185 pp. (English only). www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers/papers3.htm 1 Integrated Framework for the Management of Beach Resources within the 4 Applications of Satellite and Airborne Image Data to Coastal Management. Smaller Caribbean Islands. Workshop results. 1997. 31 pp. (English only). Seventh computer-based learning module. Edited by A. J. Edwards. 1999. www.unesco.org/csi/pub/info/pub2.htm 185 pp. (English only). www.ncl.ac.uk/tcmweb/bilko/mod7_pdf.shtml 2 UNESCO on Coastal Regions and Small Islands. -

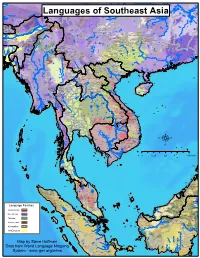

Languages of Southeast Asia

Jiarong Horpa Zhaba Amdo Tibetan Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Wu Chinese Central Tibetan Khams Tibetan Muya Huizhou Chinese Eastern Xiangxi Miao Yidu LuobaLanguages of Southeast Asia Northern Tujia Bogaer Luoba Ersu Yidu Luoba Tibetan Mandarin Chinese Digaro-Mishmi Northern Pumi Yidu LuobaDarang Deng Namuyi Bogaer Luoba Geman Deng Shixing Hmong Njua Eastern Xiangxi Miao Tibetan Idu-Mishmi Idu-Mishmi Nuosu Tibetan Tshangla Hmong Njua Miju-Mishmi Drung Tawan Monba Wunai Bunu Adi Khamti Southern Pumi Large Flowery Miao Dzongkha Kurtokha Dzalakha Phake Wunai Bunu Ta w an g M o np a Gelao Wunai Bunu Gan Chinese Bumthangkha Lama Nung Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Norra Wusa Nasu Xiang Chinese Chug Nung Wunai Bunu Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Min Bei Chinese Nupbikha Lish Kachari Ta se N a ga Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nung Large Flowery Miao Nyenkha Chalikha Sartang Lisu Nung Lisu Southern Pumi Kalaktang Monpa Apatani Khamti Ta se N a ga Wusa Nasu Adap Tshangla Nocte Naga Ayi Nung Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Nocte Naga Lisu Large Flowery Miao Northern Dong Khamti Lipo Wusa NasuWhite Miao Nepali Nepali Lhao Vo Deori Luopohe Miao Ge Southern Pumi White Miao Nepali Konyak Naga Nusu Gelao GelaoNorthern Guiyang MiaoLuopohe Miao Bodo Kachari White Miao Khamti Lipo Lipo Northern Qiandong Miao White Miao Gelao Hmong Njua Eastern Qiandong Miao Phom Naga Khamti Zauzou Lipo Large Flowery Miao Ge Northern Rengma Naga Chang Naga Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Assamese Southern Guiyang Miao Southern Rengma Naga Khamti Ta i N u a Wusa Nasu Northern Huishui -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System

Guanyinqiao Horpa Zhaba Amdo Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Chinese, Wu Muya Tibetan Khams Chinese, Huizhou Moinba Hmong, Eastern Xiangxi Luoba, Yidu Tujia, Northern Luoba, Bogaer LanguagesErsu of Southeast Asia Luoba, Yidu Tibetan Chinese, Mandarin Digaro Pumi, Northern Luoba, YiduDarang Deng Namuyi Luoba, Bogaer Geman Deng Hmong, Eastern Xiangxi Atuence Shixing Hmong Njua Tibetan Idu Idu Yi, Sichuan Tibetan Tshangla Miju Drung Hmong Njua Moinba Bunu, Wunai Hmong, Northeastern Dian Dzongkha Adi Phake Khamti Pumi, Southern Bunu, Wunai Kurtokha Dzalakha Choni Gelao Chinese, Gan Bumthangkha Moinba Lama Nung Yi, Guizhou Yi, Guizhou Bunu, Wunai Chinese, Xiang Norra Bunu, Wunai Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Chinese, Min Bei Nupbikha Kachari Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nyenkha Chalikha Naga, Tase LisuNung Lisu Hmong, Northeastern Dian Pumi, Southern Apatani Khamti Naga, Tase Yi, Guizhou Adap Tshangla Naga, Nocte Ayi Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Naga, Nocte Lisu Hmong, Northeastern Dian Dong, Northern Khamti Lipo Yi, GuizhouHmong Daw Nepali Nepali Maru Deori Hmong, LuopoheHmong, Chonganjiang Pumi, Southern Nepali Naga, Konyak Nusu Hmong Daw Gelao GelaoHmong, Northern GuiyangHmong, Luopohe Bodo Kachari Lipo Hmong Daw Khamti Lipo Gelao Hmong, Northern QiandongHmong, Eastern Qiandong Assamese Hmong, Northeastern Dian Hmong Daw Hmong Njua Naga, Phom Khamti Zauzou Lipo Hmong, Chonganjiang Naga, Ntenyi Yi, Guizhou Bunu, Wunai Hmong, Southern Guiyang Naga, Rengma Khamti Tai Nua Yi, Guizhou Hmong, Northern Huishui Bunu, Bu-Nao Naga, Ao -

The Indigenous World 2014

IWGIA THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2014 This yearbook contains a comprehensive update on the cur- rent situation of indigenous peoples and their human rights, THE INDIGENOUS WORLD and provides an overview of the most important developments in international and regional processes during 2013. In 73 articles, indigenous and non-indigenous scholars and activists provide their insight and knowledge to the book with country reports covering most of the indigenous world, and updated information on international and regional processes relating to indigenous peoples. The Indigenous World 2014 is an essential source of informa- tion and indispensable tool for those who need to be informed THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2014 about the most recent issues and developments that have impacted on indigenous peoples worldwide. 2014 INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS 3 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2014 Copenhagen 2014 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2014 Compilation and editing: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Regional editors: Arctic & North America: Kathrin Wessendorf Mexico, Central and South America: Alejandro Parellada Australia and the Pacific: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Asia: Christian Erni and Christina Nilsson The Middle East: Diana Vinding and Cæcilie Mikkelsen Africa: Marianne Wiben Jensen and Geneviève Rose International Processes: Lola García-Alix and Kathrin Wessendorf Cover and typesetting: Jorge Monrás Maps: Jorge Monrás English translation: Elaine Bolton Proof reading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark © The authors and The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), 2014 - All Rights Reserved HURRIDOCS CIP DATA The reproduction and distribution of information contained Title: The Indigenous World 2014 in The Indigenous World is welcome as long as the source Edited by: Cæcilie Mikkelsen is cited. -

Clefts and Anti-Superiority in Moken

Citation Kenneth BACLAWSKI Jr and Peter JENKS. 2016. Clefts and anti-Superiority in Moken. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 9:81-96 URL http://hdl.handle.net/1885/105175 Reviewed Received 5 April 2016, revised text accepted 11 June 2016, published July 2016 Editors Editor-In-Chief Dr Mark Alves | Managing Eds. Dr Sigrid Lew, Dr Paul Sidwell Web http://jseals.org ISSN 1836-6821 www.jseals.org | Volume 9 | 2016 | Asia-Pacific Linguistics, ANU Copyright vested in the authors; Creative Commons Attribution Licence CLEFTS AND ANTI-SUPERIORITY IN MOKEN1 Kenneth Baclawski Jr. Peter Jenks University of California, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley <[email protected]> <[email protected]> Abstract We describe an extraction asymmetry in Moken that presents apparent Anti-Superiority effects. We then show that this asymmetry is not rooted in Superiority at all. Evidence from island effects is used to demonstrate that the left-dislocation of wh-phrases is not the result of wh- movement as standardly conceived. Furthermore, the same Anti-Superiority effect obtains for non-wh-phrases and clefts. At the same time, standard Superiority effects in Moken do arise in certain environments. These observations lead to the conclusion that Anti-Superiority effects in Moken are not counterexamples to the universality of Superiority, but instead arise due to a constraint on crossed dependencies between arguments and non-argument positions. Keywords: Moken, constituent question, cleft, superiority ISO 639-3: mwt, cjm 1 Introduction The Moken language 2 (Austronesian: Thailand, Burma) displays an extraction asymmetry that, on the surface, is plainly an Anti-Superiority effect. -

Experience Form Community Training in the Moken Language Documentation and Preservation Project

Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences 39 (2018) 244e253 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/kjss Language endangerment and community empowerment: Experience form community training in the Moken language documentation and preservation project Sarawut Kraisame Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom 73170, Thailand article info ABSTRACT Article history: Language endangerment and extinction is currently a critical issue among linguists around Received 16 December 2016 the world. It is known that language attrition and loss dramatically progress, work on Received in revised form 24 March 2017 documentation and preservation should be done prior to the last speaker of such language Accepted 24 May 2017 passing away. It is found that there are at least fifteen languages in Thailand which suffer Available online 21 June 2017 from language decline and will be extinct very soon. Moken language (ISO 693-3 code mwt) is one of language which is regarded as the dying languages. Like other endangered Keywords: languages, Moken language and local heritage knowledge gradually decline without any community empowerment, transmission to younger generations. Thus, the Moken language documentation and community training, preservation project (MLDPP) was initiated with an attempt to document and preserve language documentation and preservation, Moken language and its oral literature before its extinction. As a part of MLDPP, this paper language endangerment, describes about how the community-training program is maneuvered. This contributes to Moken language collaborative language documentation and preservation project. As participatory action research, a grounded-theoretical approach together with on-the-job-training was adopted for contributing to the most benefit of community members. -

The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar Colonial History and Language Policy in Insular Southeast Asia and Madagascar

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 30 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar Alexander Adelaar, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Colonial History and Language Policy in Insular Southeast Asia and Madagascar Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203821121.ch3 Hein Steinhauer Published online on: 25 Nov 2004 How to cite :- Hein Steinhauer. 25 Nov 2004, Colonial History and Language Policy in Insular Southeast Asia and Madagascar from: The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar Routledge Accessed on: 30 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203821121.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. CHAPTER THREE COLONIAL HISTORY AND LANGUAGE POLICY IN INSULAR SOUTHEAST ASIA AND MADAGASCAR Hein Steinhauer 1 INTRODUCTION The present chapter discusses background and practice of language policy in those countries in which a majority of the population has a western Austronesian language as its mother tongue, i.e.