Burma “Sea Gypsies” Compendium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fi~Eeting Encounter with the Moken Cthe Sea Gypsies) in Southern Thailand: Some Linguistic and General Notes

A FI~EETING ENCOUNTER WITH THE MOKEN CTHE SEA GYPSIES) IN SOUTHERN THAILAND: SOME LINGUISTIC AND GENERAL NOTES by Christopher Court During a short trip (3-5 April 1970) to the islands of King Amphoe Khuraburi (formerly Koh Kho Khao) in Phang-nga Province in Southern Thailand, my curiosity was aroused by frequent references in conversation with local inhabitants to a group of very primitive people (they were likened to the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves) whose entire life was spent nomadically on small boats. It was obvious that this must be the Moken described by White ( 1922) and Bernatzik (1939, and Bernatzik and Bernatzik 1958: 13-60). By a stroke of good fortune a boat belonging to this group happened to come into the beach at Ban Pak Chok on the island of Koh Phrah Thong, where I was spending the afternoon. When I went to inspect the craft and its occupants it turned out that there were only women and children on board, the one man among the occupants having gone ashore on some errand. The women were extremely shy. Because of this, and the failing light, and the fact that I was short of film, I took only two photographs, and then left the people in peace. Later, when the man returned, I interviewed him briefly elsewhere (see f. n. 2) collecting a few items of vocabulary. From this interview and from conversations with the local residents, particularly Mr. Prapa Inphanthang, a trader who has many dealings with the Moken, I pieced together something of the life and language of these people. -

June Lawyer Kyi Myint and Poet Saw Wai Held a Press JANUARY Chronologyconference Regarding the Arrest Warrant2020 Against

June Lawyer Kyi Myint and Poet Saw Wai held a press JANUARY CHRONOLOGYconference regarding the arrest warrant2020 against them. Summary of the Current Situation: 647 individuals are oppressed in Burma due to political activity: 73 political prisoners are serving sentences, 141 are awaiting trial inside prison, 433 are awaiting trial outside Accessed January © Myanmar Times prison. WEBSITE | TWITTER | FACEBOOK January 2020 1 ACRONYMS ABFSU All Burma Federation of Student Unions CAT Conservation Alliance Tanawthari CNPC China National Petroleum Corporation EAO Ethnic Armed Organization GEF Global Environment Facility ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross IDP Internally Displaced Person KHRG Karen Human Rights Group KIA Kachin Independence Army KNU Karen National Union MFU Myanmar Farmers’ Union MNHRC Myanmar National Human Rights Commission MOGE Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise NLD National League for Democracy NNC Naga National Council PAPPL Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law RCSS Restoration Council of Shan State RCSS/SSA Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army – South SHRF Shan Human Rights Foundation TNLA Ta’ang National Liberation Army YUSU Yangon University Students’ Union January 2020 2 POLITICAL PRISONERS Note - Changes have been made to the layout and content of the Chronology. AAPP will no longer cover landmine cases and conflict between ethnic armed groups (EAGs) due to resources; detentions and torture by EAGs will still be covered. Additionally, AAPP will not cover individual protests by land rights, but will provide updates on the arrests of land rights activists. Political Prisoners ARRESTS Two RCSS members arrested in Namhsan On January 6, the military arrested two members of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) who attended a public meeting at Nar Bwe Village in Namhsan Township in southern Shan State. -

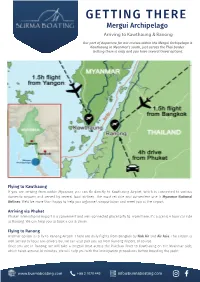

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong Our port of departure for our cruises within the Mergui Archipelago is Kawthaung in Myanmar’s south, just across the Thai border. Getting there is easy and you have several travel options. Flying to Kawthaung If you are arriving from within Myanmar, you can fly directly to Kawthaung Airport, which is connected to various domestic airports and served by several local airlines. The most reliable and convenient one is Myanmar National Airlines. We’d be more than happy to help you organise transportation and meet you at the airport. Arriving via Phuket Phuket International Airport is a convenient and well-connected place to fly to. From there, it’s a scenic 4 hour car ride to Ranong. We can help you to book a car & driver. Flying to Ranong Another option is to fly to Ranong Airport. There are daily flights from Bangkok by Nok Air and Air Asia. The airport is well served by local taxi drivers but we can also pick you up from Ranong Airport, of course. Once you are in Ranong, we will take a longtail boat across the Pakchan River to Kawthaung on the Myanmar side, which takes around 30 minutes. We will help you with the immigration procedures before boarding the yacht. www.burmaboating.com +66 2 1070 445 [email protected] GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Crossing the Thai-Myanmar border In the case you arrive through the Thailand side and doesn’t want our assistance, here is a quick step by step instruction to cross the border between the 2 countries. -

Color Terms in Thailand*

8th International Conference on Humanities, Psychology and Social Science October 19 – 21, 2018 Munich, Germany Color Terms in Thailand* Kanyarat Unthanon1 and Rattana Chanthao2 Abstract This article aims to synthesize the studies of color terms in Thailand by language family. The data’s synthesis was collected from articles, theses and research papers totaling 23 works:13 theses, 8 articles and 2 research papers. The study was divided into 23 works in five language families in Thailand : 9 works in Tai, 3 works in Austro-Asiatic (Mon-Khmer), 2 works in Sino-Tibetan, 2 works in Austronesian and 2 works in two Hmong- Mien. There are also 5 comparative studies of color terms in the same family and different families. The studies of color terms in Austro-Asiatic, Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian and Hmong- Mien in Thailand have still found rare so it should be studied further, especially, study color terms of languages in each family and between different families, both in diachronic and synchronic study so that we are able to understand the culture, belief and world outlook of native speakers through their color terms. Keywords: Color terms, Basic color term, Non-basis color term, Ethic groups * This article is a part of a Ph.D. thesis into an article “Color Terms in Modern Thai” 1 Ph.D.student of Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Thailand 2Assistant Professor of Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Thailand : Thesis’s Advisor 1. Background The studies of color terms in Thailand are the research studies of languages in ethnic linguistics (Ethnolinguistics) by collecting language data derived directly from the key informants, which is called primary data or collection data from documents which is called secondary data. -

The Linguistic Background to SE Asian Sea Nomadism

The linguistic background to SE Asian sea nomadism Chapter in: Sea nomads of SE Asia past and present. Bérénice Bellina, Roger M. Blench & Jean-Christophe Galipaud eds. Singapore: NUS Press. Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Department of History, University of Jos Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, March 21, 2017 Roger Blench Linguistic context of SE Asian sea peoples Submission version TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. The broad picture 3 3. The Samalic [Bajau] languages 4 4. The Orang Laut languages 5 5. The Andaman Sea languages 6 6. The Vezo hypothesis 9 7. Should we include river nomads? 10 8. Boat-people along the coast of China 10 9. Historical interpretation 11 References 13 TABLES Table 1. Linguistic affiliation of sea nomad populations 3 Table 2. Sailfish in Moklen/Moken 7 Table 3. Big-eye scad in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 4. Lake → ocean in Moklen 8 Table 5. Gill-net in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 6. Hearth on boat in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 7. Fishtrap in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 8. ‘Bracelet’ in Moklen/Moken 8 Table 9. Vezo fish names and their corresponding Malayopolynesian etymologies 9 FIGURES Figure 1. The Samalic languages 5 Figure 2. Schematic model of trade mosaic in the trans-Isthmian region 12 PHOTOS Photo 1. Orang Laut settlement in Riau 5 Photo 2. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

TANINTHARYI REGION, MYEIK DISTRICT Palaw Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census TANINTHARYI REGION, MYEIK DISTRICT Palaw Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Tanintharyi Region, Myeik District Palaw Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Tanintharyi Region, showing the townships Palaw Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 93,438 2 Population males 45,366 (48.6%) Population females 48,072 (51.4%) Percentage of urban population 20.3% Area (Km2) 1,652.3 3 Population density (per Km2) 56.6 persons Median age 22.9 years Number of wards 5 Number of village tracts 20 Number of private households 18,525 Percentage of female headed households 24.2 % Mean household size 5.0 persons4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 35.7% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 58.8% Elderly population (65+ years) 5.5% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 70.1 Child dependency ratio 60.7 Old dependency ratio 9.4 Ageing index 15.5 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 94 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 94.4% Male 94.9% Female 94.0% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 9,018 9.7 Walking 3,137 3.4 Seeing 5,655 6.1 Hearing 2,464 2.6 Remembering 2,924 3.1 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 51,835 -

Military Brotherhood Between Thailand and Myanmar: from Ruling to Governing the Borderlands

1 Military Brotherhood between Thailand and Myanmar: From Ruling to Governing the Borderlands Naruemon Thabchumphon, Carl Middleton, Zaw Aung, Surada Chundasutathanakul, and Fransiskus Adrian Tarmedi1, 2 Paper presented at the 4th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference “Activated Borders: Re-openings, Ruptures and Relationships”, 8-10 December 2014 Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction Signaling a new phase of cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar, on 9 October 2014, Thailand’s new Prime Minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha took a two-day trip to Myanmar where he met with high-ranked officials in the capital Nay Pi Taw, including President Thein Sein. That this was Prime Minister Prayuth’s first overseas visit since becoming Prime Minister underscored the significance of Thailand’s relationship with Myanmar. During their meeting, Prime Minister Prayuth and President Thein Sein agreed to better regulate border areas and deepen their cooperation on border related issues, including on illicit drugs, formal and illegal migrant labor, including how to more efficiently regulate labor and make Myanmar migrant registration processes more efficient in Thailand, human trafficking, and plans to develop economic zones along border areas – for example, in Mae 3 Sot district of Tak province - to boost trade, investment and create jobs in the areas . With a stated goal of facilitating border trade, 3 pairs of adjacent provinces were named as “sister provinces” under Memorandums of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand signed by the respective Provincial governors during the trip.4 Sharing more than 2000 kilometer of border, both leaders reportedly understood these issues as “partnership matters for security and development” (Bangkok Post, 2014). -

• Similan Islands • Ko Bon/Ko Tachai • Richelieu Rock • Mergui Archipelago

Takes you to the BEST dive sites of Thailand and Burma (Myanmar): Similan Islands Ko Bon/Ko Tachai Richelieu Rock Mergui Archipelago 5 day 4 night trips to Similan Islands, Ko Bon, Ko Tachai & Richelieu Rock—13/14 dives 8 day 7 night trips to include Mergui Archipelago, Burma—20/22 dives MV Deep Andaman Queen is a 28m long and 7m wide steel-hulled boat. The most spacious dive deck and platform of any diving liveaboard in Thailand! One of the most popular liveaboard choices and for good reason! Accommodates a maximum of 21 divers in comfortable air conditioned cabins—all cabins have private bathroom and hot water. The Master cabin has one of the best panoramic ocean views of any Thailand liveaboard. Meals are freshly prepared on board. There is spacious seating area directly at the front of the boat, as well as sun chairs, loungers and sofas on the very top deck. Power points can be found in all cabins, with additional power points in the saloon for those wanting to charge the batteries of cameras and other technical devices. Standard Standard Standard DURATION DESTINATION Master VIP Twin Triple Quad 4 day/4 night Thailand (14 dives) 46000 40000 35700 32000 30000 5 day/5 night Thailand (18 dives) 63250 55000 48125 44000 41250 (Xmas/NY) Burma & Thailand 7 day/7 night 87500 77000 68250 63000 59500 (22 dives) Price includes transfer hotel in Phuket/Khao Lak—boat—hotel, full board, soft drinks, tanks, weights, weight belt and experienced dive guide. Price does NOT include: National Park Fee (1800.-THB 4 day / 2000.-THB 5 day), alcoholic drinks, torch for night dive, NITROX, diving equipment (full set = 700.-THB per day), dive computer (500.-THB per day). -

Transport Logistics

MYANMAR TRADE FACILITATION THROUGH LOGISTCS CONNECTIVITY HLA HLA YEE BITEC , BANGKOK 4.9.15 [email protected] Total land area 677,000sq km Total length (South to North) 2,100km (East to West) 925km Total land boundaries 5,867km China 2,185km Lao 235km Thailand 1,800km Bangladesh 193km India 1,463km Total length of coastline 2,228km Capital : Naypyitaw Language :Myanmar MYANMAR IN 2015 REFORM & FAST ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS SIGNIFICANT POTENTIAL CREDIBILITY AMONG ASEAN NATIONS GATE WAY “ CHINA & INDIA & ASEAN” MAXIMIZING MULTIMODALTRANSPORT LINKAGES EXPEND GMS ECONOMIC TRANSPORT CORRIDORS EFFECTIVE EXTENSION INTO MYANMAR INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTION TRADE AND LOTISGICS SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY & PREDICTABILITY LEGAL & REGULATORY FREAMEWORK INFRASTUCTURE INFORMATION CORRUPTION FIANACIAL SERVICE “STRENGTHEING SME LOGISTICS” INDUSTRIAL ZONE DEVELOPMENT 7 NEW IZ KYAUk PHYU Yadanarbon(MDY) SEZ Tart Kon (NPD) Nan oon Pa han 18 Myawadi Three pagoda Existing IZ Pon nar island Yangon(4) Mandalay Meikthilar Myingyan Yenangyaing THI LA WAR Pakokku SEZ Monywa Pyay Pathein DAWEI Myangmya SEZ Hinthada Mawlamyaing Myeik Taunggyi Kalay INDUSTRIES CATEGORIES Competitive Industries Potential Industries Basic Industries Food and Beverages Automobile Parts Agricultural Machinery Garment & Textile Industrial Materials Agricultural Fertilizer Household Woodwork Minerals & Crude Oil Machinery & spare parts Gems & Jewelry Pharmaceutical Electrical & Electronics Construction Materials Paper & Publishing Renewable Energy Household products TRANSPORT -

Southeast-Asia-On-A-Shoestring-17-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Southeast Asia on a shoestring Myanmar (Burma) p480 Laos p311 Thailand Vietnam p643 p812 Cambodia Philippines p64 p547 Brunei Darussalam p50 Malaysia p378 Singapore p613 Indonesia Timor- p149 Leste p791 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY China Williams, Greg Bloom, Celeste Brash, Stuart Butler, Shawn Low, Simon Richmond, Daniel Robinson, Iain Stewart, Ryan Ver Berkmoes, Richard Waters PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUNEI Batu .Karas. 169 Southeast Asia . .6 DARUSSALAM . 50 Wonosobo. 170 Southeast Asia Map . .8 Bandar Seri Begawan . 53 Dieng .Plateau. 170 Southeast Asia’s Top 20 . .10 Jerudong. 58 Yogyakarta. 171. Muara. 59 Prambanan. 179 Need to Know . 20 Temburong.District. 59 Borobudur. 179 First Time Understand Brunei Solo .(Surakarta). 182 Southeast Asia . 22 Darussalam . 60 Malang .&.Around. 185 If You Like… . 24 Survival Guide . 61 Gunung .Bromo. 187 Month by Month . 26 CAMBODIA . 64 Bondowoso. 190 Ijen .Plateau. 190 Itineraries . 30 Phnom Penh . 68 Banyuwangi. 191 Off the Beaten Track . 36 Siem Reap & the Temples of Angkor . 85 Bali . .191 Big Adventures, Siem .Reap. 86 Kuta, .Legian,.Seminyak.. Small Budget . 38 & .Kerabokan. 195 Templesf .o .Angkor. 94 Canggu .Area. .202 Countries at a Glance . 46 Northwestern Cambodia . 103 Bukit .Peninsula .. .. .. .. .. .. ...202 Battambang.. 103 Denpasar. .204 117 IMAGERY/GETTY IMAGES © Prasat .Preah.Vihear.. 108 Sanur. .206 Kompong .Thom.. 110 Nusa .Lembongan. 207 South Coast . 111 Ubud. .208 Koh .Kong.City.. .111 East .Coast.Beaches. 215 Koh .Kong.. Semarapura.(Klungkung). 215. Conservation.Corridor . 114 Sidemen .Road . 215 Sihanoukville.. 114 Padangbai. 215 The .Southern.Islands . 121 Candidasa. 216 Kampot.. 122 Tirta .Gangga. -

Literature for the SECU Desk Review Dear Paul, Anne and the SECU

Literature for the SECU Desk Review Dear Paul, Anne and the SECU team, We are writing to you to provide you with what we consider to be important documents in your investigation into community complaints of the Ridge to Reef Project. The following documents provide background to the affected community and the political situation in Tanintharyi Region, on the history and design of the project, on the grievances and concerns of the local community with respect to the project, and aspirations and efforts of indigenous communities who are working towards an alternative vision of conservation in Tanintharyi Region. The documents mentioned in this letter are enclosed in this email. All documents will be made public. Background to the affected community Tanintharyi Region is home to one of the widest expanses of contiguous low to mid elevation evergreen forest in South East Asia, home to a vast variety of vulnerable and endangered flora and fauna species. Indigenous Karen communities have lived within this landscape for generations, managing land and forests under customary tenure systems that have ensured the sustainable use of resources and the protection of key biodiversity, alongside forest based livelihoods. The region has a long history of armed conflict. The area initially became engulfed in armed conflict in December 1948 when Burmese military forces attacked Karen Defence Organization outposts and set fire to several villages in Palaw Township. Conflict became particularly bad in 1991 and 1997, when heavy attacks were launched by the Burmese military against KNU outposts, displacing around 80,000 people.1 Throughout the conflict communities experienced many serious human rights abuses, many villages were burnt down, and tens of thousands of people were forced to flee to the Thai border, the forest or to government controlled zones.2 Armed conflict came to a halt in 2012 following a bi-lateral ceasefire agreement between the KNU and the Myanmar government, which was subsequently followed by KNU signing of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement in 2015.