Clefts and Anti-Superiority in Moken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fi~Eeting Encounter with the Moken Cthe Sea Gypsies) in Southern Thailand: Some Linguistic and General Notes

A FI~EETING ENCOUNTER WITH THE MOKEN CTHE SEA GYPSIES) IN SOUTHERN THAILAND: SOME LINGUISTIC AND GENERAL NOTES by Christopher Court During a short trip (3-5 April 1970) to the islands of King Amphoe Khuraburi (formerly Koh Kho Khao) in Phang-nga Province in Southern Thailand, my curiosity was aroused by frequent references in conversation with local inhabitants to a group of very primitive people (they were likened to the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves) whose entire life was spent nomadically on small boats. It was obvious that this must be the Moken described by White ( 1922) and Bernatzik (1939, and Bernatzik and Bernatzik 1958: 13-60). By a stroke of good fortune a boat belonging to this group happened to come into the beach at Ban Pak Chok on the island of Koh Phrah Thong, where I was spending the afternoon. When I went to inspect the craft and its occupants it turned out that there were only women and children on board, the one man among the occupants having gone ashore on some errand. The women were extremely shy. Because of this, and the failing light, and the fact that I was short of film, I took only two photographs, and then left the people in peace. Later, when the man returned, I interviewed him briefly elsewhere (see f. n. 2) collecting a few items of vocabulary. From this interview and from conversations with the local residents, particularly Mr. Prapa Inphanthang, a trader who has many dealings with the Moken, I pieced together something of the life and language of these people. -

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

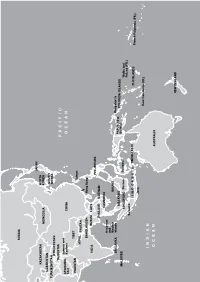

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

The Malayic-Speaking Orang Laut Dialects and Directions for Research

KARLWacana ANDERBECK Vol. 14 No., The 2 Malayic-speaking(October 2012): 265–312Orang Laut 265 The Malayic-speaking Orang Laut Dialects and directions for research KARL ANDERBECK Abstract Southeast Asia is home to many distinct groups of sea nomads, some of which are known collectively as Orang (Suku) Laut. Those located between Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula are all Malayic-speaking. Information about their speech is paltry and scattered; while starting points are provided in publications such as Skeat and Blagden (1906), Kähler (1946a, b, 1960), Sopher (1977: 178–180), Kadir et al. (1986), Stokhof (1987), and Collins (1988, 1995), a comprehensive account and description of Malayic Sea Tribe lects has not been provided to date. This study brings together disparate sources, including a bit of original research, to sketch a unified linguistic picture and point the way for further investigation. While much is still unknown, this paper demonstrates relationships within and between individual Sea Tribe varieties and neighbouring canonical Malay lects. It is proposed that Sea Tribe lects can be assigned to four groupings: Kedah, Riau Islands, Duano, and Sekak. Keywords Malay, Malayic, Orang Laut, Suku Laut, Sea Tribes, sea nomads, dialectology, historical linguistics, language vitality, endangerment, Skeat and Blagden, Holle. 1 Introduction Sometime in the tenth century AD, a pair of ships follows the monsoons to the southeast coast of Sumatra. Their desire: to trade for its famed aromatic resins and gold. Threading their way through the numerous straits, the ships’ path is a dangerous one, filled with rocky shoals and lurking raiders. Only one vessel reaches its destination. -

19 Chapter 2. Cyclic and Noncyclic Phonological Effects a Proper

Chapter 2. Cyclic and noncyclic phonological effects A proper theory of the phonology-morphology interface must account for apparent cyclic phonological effects as well as noncyclic phonological effects. Cyclic phonological effects are those in which a morphological subconstituent of a word seems to be an exclusive domain for some phonological rule or constraint. In this chapter, I show how Sign-Based Morphology can handle noncyclic as well as cyclic phonological effects. Furthermore, Sign-Based Morphology, unlike other theories of the phonology-morphology interface, relates the cyclic-noncyclic contrast to independently motivatable morphological structures. 2.1 Turkish prosodic minimality The example in this section is a disyllabic minimal size condition that some speakers of Standard Istanbul Turkish impose on affixed forms (Itô and Hankamer 1989, Inkelas and Orgun 1995). The examples in (28b) show that affixed monosyllabic forms are ungrammatical for these speakers (unaffixed monosyllabic forms are accepted (28a), as are semantically similar polysyllabic affixed forms (29b). (28) a) GRÛ ‘musical note C’ b) *GRÛ-P ‘C-1sg.poss’ MH ‘eat’ *MH-Q ‘eat-pass’ (29) a) VRO- ‘musical note G’ b) VRO--\P ‘G-1sg.poss’ N$]$Û ‘accident’ N$]$Û-P ‘accident-1sg.poss’ MXW ‘swallow’ MXW-XO ‘swallow-pass’ WHN-PHO-H ‘kick’ WHN-PHO-H-Q ‘kick-pass’ What happens when more suffixes are added to the forms in (28b) to bring the total size to two syllables? It turns out that nominal forms with additional affixes are still ungrammatical regardless of the total size, as shown by the data in (30). (30) *GRÛ-P ‘C-1sg.poss’ *GRÛ-P-X ‘C-1sg.poss’ *UHÛ-Q ‘D-2sg.poss’ *UHÛ-Q-GHQ ‘D-2sg.poss-abl’ *I$Û-P ‘F-1sg.poss’ *I$Û-P-V$ ‘F-1sg.poss-cond’ These forms suggest that the disyllabic minimal size condition is enforced cyclically. -

'Undergoer Voice in Borneo: Penan, Punan, Kenyah and Kayan

Undergoer Voice in Borneo Penan, Punan, Kenyah and Kayan languages Antonia SORIENTE University of Naples “L’Orientale” Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology-Jakarta This paper describes the morphosyntactic characteristics of a few languages in Borneo, which belong to the North Borneo phylum. It is a typological sketch of how these languages express undergoer voice. It is based on data from Penan Benalui, Punan Tubu’, Punan Malinau in East Kalimantan Province, and from two Kenyah languages as well as secondary source data from Kayanic languages in East Kalimantan and in Sawarak (Malaysia). Another aim of this paper is to explore how the morphosyntactic features of North Borneo languages might shed light on the linguistic subgrouping of Borneo’s heterogeneous hunter-gatherer groups, broadly referred to as ‘Penan’ in Sarawak and ‘Punan’ in Kalimantan. 1. The North Borneo languages The island of Borneo is home to a great variety of languages and language groups. One of the main groups is the North Borneo phylum that is part of a still larger Greater North Borneo (GNB) subgroup (Blust 2010) that includes all languages of Borneo except the Barito languages of southeast Kalimantan (and Malagasy) (see Table 1). According to Blust (2010), this subgroup includes, in addition to Bornean languages, various languages outside Borneo, namely, Malayo-Chamic, Moken, Rejang, and Sundanese. The languages of this study belong to different subgroups within the North Borneo phylum. They include the North Sarawakan subgroup with (1) languages that are spoken by hunter-gatherers (Penan Benalui (a Western Penan dialect), Punan Tubu’, and Punan Malinau), and (2) languages that are spoken by agriculturalists, that is Òma Lóngh and Lebu’ Kulit Kenyah (belonging respectively to the Upper Pujungan and Wahau Kenyah subgroups in Ethnologue 2009) as well as the Kayan languages Uma’ Pu (Baram Kayan), Busang, Hwang Tring and Long Gleaat (Kayan Bahau). -

The Sea Within: Marine Tenure and Cosmopolitical Debates

THE SEA WITHIN MARINE TENURE AND COSMOPOLITICAL DEBATES Hélène Artaud and Alexandre Surrallés editors IWGIA THE SEA WITHIN MARINE TENURE AND COSMOPOLITICAL DEBATES Copyright: the authors Typesetting: Jorge Monrás Editorial Production: Alejandro Parellada HURIDOCS CIP DATA Title: The sea within – Marine tenure and cosmopolitical debates Edited by: Hélène Artaud and Alexandre Surrallés Print: Tarea Asociación Gráfica Educativa - Peru Pages: 226 ISBN: Language: English Index: 1. Indigenous Peoples – 2. Maritime Rights Geografical area: world Editorial: IWGIA Publications date: April 2017 INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmak Tel: (+45) 35 27 05 00 – E-mail: [email protected] – Web: www.iwgia.org To Pedro García Hierro, in memoriam Acknowledgements The editors of this book would like to thank the authors for their rigour, ef- fectiveness and interest in our proposal. Also, Alejandro Parellada of IWGIA for the enthusiasm he has shown for our project. And finally, our thanks to the Fondation de France for allowing us, through the “Quels littoraux pour demain? [What coastlines for tomorrow?] programme to bring to fruition the reflection which is the subject of this book. Content From the Land to the Sea within – A presentation Alexandre Surrallés................................................................................................ .. 11 Introduction Hélène Artaud...................................................................................................... ....15 PART I -

Relating Application Frequency to Morphological Structure: the Case of Tommo So Vowel Harmony*

Relating application frequency to morphological structure: the case of Tommo So vowel harmony* Laura McPherson (Dartmouth College) and Bruce Hayes (UCLA) Abstract We describe three vowel harmony processes of Tommo So (Dogon, Mali) and their interaction with morphological structure. The verbal suffixes of Tommo So occur in a strict linear order, establishing a Kiparskian hierarchy of distance from the root. This distance is respected by all three harmony processes; they “peter out”, applying with lower frequency as distance from the root increases. The function relating application rate to distance is well fitted by families of sigmoid curves, declining in frequency from one to zero. We show that, assuming appropriate constraints, such functions are a direct consequence of Harmonic Grammar. The crucially conflicting constraints are IDENT (violated just once by harmonized candidates) and a scalar version of AGREE (violated 1- 7 times, based on closeness of the target to the root). We show that our model achieves a close fit to the data while a variety of alternative models fail to do so. * We would like to thank Robert Daland, Abby Hantgan, Jeffrey Heath, Kie Zuraw, audiences at the Linguistic Society of America, the Manchester Phonology Meeting, Academia Sinica, Dartmouth College and UCLA, and the anonymous reviewers and editors for Phonology for their help with this article; all remaining defects are the authors’ responsibility. We are also indebted to the Tommo So language consultants who provided all of the data. This research was supported by a grant from the Fulbright Foundation and by grants BCS-0537435 and BCS-0853364 from the U.S. -

1.2 the Urak Lawoi

'%/!4,!3¸ 7/2,$ 6%#4/2 '2!0() /'2%¸ &RANCE - !9!.-! 2 Other titles in the CSI series 20 Communities in Action: Sharing the experiences. Report on ‘Mauritius ,!/ 3 Coastal region and small island papers: Strategy Implementation: Small Islands Voice Planning Meeting’, Bequia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, 11-16 July 2005. 50 pp. (English only). 1 Managing Beach Resources in the Smaller Caribbean Islands. Workshop Available electronically only at: www.unesco.org/csi/smis/siv/inter-reg/ Papers. Edited by Gillian Cambers. 1997. 269 pp. (English only). SIVplanmeet-svg3.htm www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers/papers1.htm 21 Exit from the Labyrinth. Integrated Coastal Management in the 2 Coasts of Haiti. Resource Assessment and Management Needs. 1998. Kandalaksha District, Murmansk Region of the Russian Federation. 2006. 75 39 pp. (English and French). pp. (English). www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers4/lab.htm www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers/papers2.htm www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers/papiers2.htm 3 CARICOMP – Caribbean Coral Reef, Seagrass and Mangrove Sites. Titles in the CSI info series: Edited by Björn Kjerfve. 1999. 185 pp. (English only). www.unesco.org/csi/pub/papers/papers3.htm 1 Integrated Framework for the Management of Beach Resources within the 4 Applications of Satellite and Airborne Image Data to Coastal Management. Smaller Caribbean Islands. Workshop results. 1997. 31 pp. (English only). Seventh computer-based learning module. Edited by A. J. Edwards. 1999. www.unesco.org/csi/pub/info/pub2.htm 185 pp. (English only). www.ncl.ac.uk/tcmweb/bilko/mod7_pdf.shtml 2 UNESCO on Coastal Regions and Small Islands. -

The Effects of Duration and Sonority on Contour Tone Distribution— Typological Survey and Formal Analysis

The Effects of Duration and Sonority on Contour Tone Distribution— Typological Survey and Formal Analysis Jie Zhang For my family Table of Contents Acknowledgments xi 1 Background 3 1.1 Two Examples of Contour Tone Distribution 3 1.1.1 Contour Tones on Long Vowels Only 3 1.1.2 Contour Tones on Stressed Syllables Only 8 1.2 Questions Raised by the Examples 9 1.3 How This Work Evaluates The Different Predictions 11 1.3.1 A Survey of Contour Tone Distribution 11 1.3.2 Instrumental Case Studies 11 1.4 Putting Contour Tone Distribution in a Bigger Picture 13 1.4.1 Phonetically-Driven Phonology 13 1.4.2 Positional Prominence 14 1.4.3 Competing Approaches to Positional Prominence 16 1.5 Outline 20 2 The Phonetics of Contour Tones 23 2.1 Overview 23 2.2 The Importance of Sonority for Contour Tone Bearing 23 2.3 The Importance of Duration for Contour Tone Bearing 24 2.4 The Irrelevance of Onsets to Contour Tone Bearing 26 2.5 Local Conclusion 27 3 Empirical Predictions of Different Approaches 29 3.1 Overview 29 3.2 Defining CCONTOUR and Tonal Complexity 29 3.3 Phonological Factors That Influence Duration and Sonority of the Rime 32 3.4 Predictions of Contour Tone Distribution by Different Approaches 34 3.4.1 The Direct Approach 34 3.4.2 Contrast-Specific Positional Markedness 38 3.4.3 General-Purpose Positional Markedness 41 vii viii Table of Contents 3.4.4 The Moraic Approach 42 3.5 Local Conclusion 43 4 The Role of Contrast-Specific Phonetics in Contour Tone Distribution: A Survey 45 4.1 Overview of the Survey 45 4.2 Segmental Composition 48 -

Two Types of Portmanteau Agreement: Syntactic and Morphological1

January 2014 manuscript To apppear in Advances in OT Syntax and Semantics, edited by Geraldine Legendre, Michael Putnam, and Erin Zaroukian. Oxford University Press. (Paper presented at the Optimality Theory Workshop, Johns Hopkins University, Nov 2012) Two Types of Portmanteau Agreement: Syntactic and Morphological1 Ellen Woolford University of Massachusetts A portmanteau agreement morpheme is one that encodes features from more than one argument. An example can be seen in (1) from Guarani where the portmanteau agreement morpheme roi spells out the first person feature from the subject and the second person feature from the object. (1) Roi-su’ú-ta. [Guarani] 1-2sg-bite-future ‘I will bite you.’ (Tonhauser 2006:133 (8a)) This portmanteau morpheme is distinct from the agreement morpheme that cross-references the first person subject, in (2), and from the morpheme that cross-references the second person object in (3). (2) A-ha-ta. [Guarani] 1sg-go-future ‘I will go.’ (Tonhuaser 2006:133 (9a)) (3) Petei jagua nde-su’u. one dog 2sg-bite ‘A dog bit you.’ (Velázquez Castillo 1996:17 (14)) The goal of this paper is to answer the question of where and how portmanteau agreement is formed in the grammar. This is a matter of considerable debate in the current literature. Georgi 2011 argues that all portmanteau agreement is created in syntax, with Infl/T probing two arguments. Williams 2003 argues that what is crucial for portmanteau morphemes of any kind is 1 I would like to thank the participants in the November 2012 Advances in Optimality Theoretic-Syntax and Semantics Workshop at Johns Hopkins University and the anonymous reviewer for this volume for valuable comments on this paper. -

Languages of Southeast Asia

Jiarong Horpa Zhaba Amdo Tibetan Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Wu Chinese Central Tibetan Khams Tibetan Muya Huizhou Chinese Eastern Xiangxi Miao Yidu LuobaLanguages of Southeast Asia Northern Tujia Bogaer Luoba Ersu Yidu Luoba Tibetan Mandarin Chinese Digaro-Mishmi Northern Pumi Yidu LuobaDarang Deng Namuyi Bogaer Luoba Geman Deng Shixing Hmong Njua Eastern Xiangxi Miao Tibetan Idu-Mishmi Idu-Mishmi Nuosu Tibetan Tshangla Hmong Njua Miju-Mishmi Drung Tawan Monba Wunai Bunu Adi Khamti Southern Pumi Large Flowery Miao Dzongkha Kurtokha Dzalakha Phake Wunai Bunu Ta w an g M o np a Gelao Wunai Bunu Gan Chinese Bumthangkha Lama Nung Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Norra Wusa Nasu Xiang Chinese Chug Nung Wunai Bunu Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Min Bei Chinese Nupbikha Lish Kachari Ta se N a ga Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nung Large Flowery Miao Nyenkha Chalikha Sartang Lisu Nung Lisu Southern Pumi Kalaktang Monpa Apatani Khamti Ta se N a ga Wusa Nasu Adap Tshangla Nocte Naga Ayi Nung Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Nocte Naga Lisu Large Flowery Miao Northern Dong Khamti Lipo Wusa NasuWhite Miao Nepali Nepali Lhao Vo Deori Luopohe Miao Ge Southern Pumi White Miao Nepali Konyak Naga Nusu Gelao GelaoNorthern Guiyang MiaoLuopohe Miao Bodo Kachari White Miao Khamti Lipo Lipo Northern Qiandong Miao White Miao Gelao Hmong Njua Eastern Qiandong Miao Phom Naga Khamti Zauzou Lipo Large Flowery Miao Ge Northern Rengma Naga Chang Naga Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Assamese Southern Guiyang Miao Southern Rengma Naga Khamti Ta i N u a Wusa Nasu Northern Huishui -

Uu Clicks Correlate with Phonotactic Patterns Amanda L. Miller

Tongue body and tongue root shape differences in N|uu clicks correlate with phonotactic patterns Amanda L. Miller 1. Introduction There is a phonological constraint, known as the Back Vowel Constraint (BVC), found in most Khoesan languages, which provides information as to the phonological patterning of clicks. BVC patterns found in N|uu, the last remaining member of the !Ui branch of the Tuu family spoken in South Africa, have never been described, as the language only had very preliminary documentation undertaken by Doke (1936) and Westphal (1953–1957). In this paper, I provide a description of the BVC in N|uu, based on lexico-statistical patterns found in a database that I developed. I also provide results of an ultrasound study designed to investigate posterior place of articulation differences among clicks. Click consonants have two constrictions, one anterior, and one posterior. Thus, they have two places of articulation. Phoneticians since Doke (1923) and Beach (1938) have described the posterior place of articulation of plain clicks as velar, and the airstream involved in their production as velaric. Thus, the anterior place of articulation was thought to be the only phonetic property that differed among the various clicks. The ultrasound results reported here and in Miller, Brugman et al. (2009) show that there are differences in the posterior constrictions as well. Namely, tongue body and tongue root shape differences are found among clicks. I propose that differences in tongue body and tongue root shape may be the phonetic bases of the BVC. The airstream involved in click production is described as velaric airstream by earlier researchers.