Cognitive Disorders: a Perspective from the Neurology Clinic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

Behavorial Health Department – Primary Care Center and Fireweed Treatment Guidelines for Cognitive Disorders

BEHAVORIAL HEALTH DEPARTMENT – PRIMARY CARE CENTER AND FIREWEED TREATMENT GUIDELINES FOR COGNITIVE DISORDERS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION AND STATEMENT OF INTENT .................................................................................2 DEFINITION OF DISORDER......................................................................................................2 GENERAL GOALS OF TREATMENT ..............................................................................................3 SUMMARY OF 1ST, 2ND AND 3RD LINE TREATMENT ............................................................................3 CLINICAL AND DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUES THAT INFLUENCE TREATMENT PLANNING..........................................3 FLOW DIAGRAM ............................................................................................................. 4 ASSESSMENT.................................................................................................................. 5 PSYCHIATRIC ASSESSMENT ....................................................................................................5 PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTING ......................................................................................................5 SCREENING/SCALES ............................................................................................................5 MODALITIES & TREATMENT MODELS............................................................................. -

Metacognition in Functional Cognitive Disorder

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.24.21259245; this version posted June 25, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title Page Title: Metacognition in Functional Cognitive Disorder Short Running Title: Functional Cognitive Disorder Authors: Rohan Bhome,1,* Andrew McWilliams,2,3,4,* Gary Price5, Norman A Poole6, Robert J Howard7, Stephen M Fleming3,8,9, Jonathan D Huntley7 *These authors contributed equally to this work 1. Dementia Research Centre, University College London, 8-11 Queen Square, London, UK 2. Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London UK. 3. Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, UK. 4. UCL Institute of Child Health, Great Ormond Street, London, UK. 5. National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, UK 6. South West London and St George's Mental Health NHS Trust, London, UK 7. Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK 8. Max Planck University College London Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research, London, UK 9. Department of Experimental Psychology, University College London, London, UK Correspondence to: Dr Rohan Bhome, Dementia Research Centre, University College London, 8-11 Queen Square, WC1N 3AR, [email protected] Word count: 4176 words 4 tables, 3 figures NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY in KOŠICE Dissociative Amnesia: a Clinical and Theoretical Reconsideration DEGREE THESIS

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Košice 2017 PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE FIRST DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHIATRY Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Thesis supervisor: Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Košice 2017 Analytical sheet Author Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão Thesis title Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Language of the thesis English Type of thesis Degree thesis Number of pages 89 Academic degree M.D. University Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice Faculty Faculty of Medicine Department/Institute Department of Psychiatry Study branch General Medicine Study programme General Medicine City Košice Thesis supervisor Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Date of submission 06/2017 Date of defence 09/2017 Key words Dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, dissociative identity disorder Thesis title in the Disociatívna amnézia: klinické a teoretické prehodnotenie Slovak language Key words in the Disociatívna amnézia, disociatívna fuga, disociatívna porucha identity Slovak language Abstract in the English language Dissociative amnesia is a one of the most intriguing, misdiagnosed conditions in the psychiatric world. Dissociative amnesia is related to other dissociative disorders, such as dissociative identity disorder and dissociative fugue. Its clinical features are known -

Paranoid Or Bizarre Delusions, Or Disorganized Speech and Thinking, and It Is Accompanied by Significant Social Or Occupational Dysfunction

Personality Disturbance Gathering, nr.34 (key to possible disturbances) Every person may be used only once, and all conditions best match one character. 1. Agoraphobia – The fear of having a panic attack in a setting from which there is no easy means of escape. 2. Alcoholism – Characterized by frequent and uncontrolled consumption of alcohol despite its negative effects on the drinker's health, relationships, and social standing. 3. Anorexia –An eating disorder characterized by refusal to maintain a healthy body weight, and an obsessive fear of gaining weight due to a distorted self image. 4. Bipolar Personality Disorder – Defined by the presence of one or more episodes of abnormally elevated energy levels, cognition, and mood with or without one or more depressive episodes. 5. Bulimia – An eating disorder characterized by recurrent binge eating, followed by compensatory behaviors. 6. Co-Dependant Relationship – A tendency to behave in overly passive or excessively caretaking ways that negatively impact one's relationships and quality of life. It often involves putting one's own needs at a lower priority than others while being excessively preoccupied with the needs of others. 7. Cognitive Distortions / all-of-nothing thinking (Splitting) – Thinking of things in absolute terms, like "always", "every", "never", and "there is no alternative". 8. Cognitive Distortions / Mental Filter – Focusing almost exclusively on certain, usually negative or upsetting, aspects of an event while ignoring other positive aspects. 9. Cognitive Distortions / Disqualifying the Positive – Continually reemphasizing or "shooting down" positive experiences for arbitrary reasons. 10. Cognitive Disorder / Labeling and Mislabeling – Explaining behaviors or events, merely by naming them in an over-generalized manner. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

Dementia: Definitions, Description and Assessments

Dementia: Definitions, Description and Assessments Beatrice Groene, MD October 24, 2019 Today’s learning objectives are: 1. To better understand normal cognitive function 2. To recognize differences between normal aging, Minor Cognitive Disorder, Major Cognitive Disorder and Dementia 3. To identify conditions often confused with dementia 4. To understand the specific information used in assessing a patient for dementia Cognitive Function Cognitive function is how we acquire and process information. • Attention - Being able to stay focused on something despite distractions, and long enough to get the needed information • Perception - The information we take in with our 5 senses • Memory- Includes short term, intermediate and long term • Executive function- Judgement and decision-making Executive Function IS VITAL TO SAFETY/DANGER AWARENESS • How we make decisions, solve problems and use judgment • The ability to make any plan (however simple) and follow an appropriate sequence of action • Response to feedback and error correction • Socially appropriate behavior What are normal changes in brain function seen with aging? The MOST COMMON symptom of a normally aging brain is SLOWER processing of information • An aging brain can still process NEW information, but it’s slower than it used to be • An aging brain becomes less efficient and is forgetful for general things like names and numbers • Because of the forgetfulness, a normally aging brain has a greater need for information to be IN CONTEXT in order to be retrieved On the positive side… • A normal aging brain retains general knowledge and vocabulary • Retains memory for relevant, well-learned material • Retains recall of past personal or historic events Normal aging adults without dementia will still have decreasing brain function • Only about 4% of normal adults between ages 65-69 will have moderate to severe memory problems (require some support) • But that number increases to 36% by age 85 • Even without dementia, the risk for memory problems increases with age. -

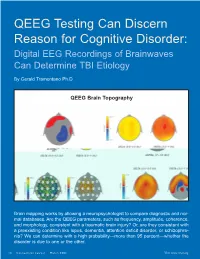

QEEG Testing Can Discern Reason for Cognitive Disorder: Digital EEG Recordings of Brainwaves Can Determine TBI Etiology

QEEG Testing Can Discern Reason for Cognitive Disorder: Digital EEG Recordings of Brainwaves Can Determine TBI Etiology By Gerald Tramontano Ph.D. QEEG Brain Topography Brain mapping works by allowing a neuropsychologist to compare diagnostic and nor- mal databases. Are the QEEG parameters, such as frequency, amplitude, coherence, and morphology, consistent with a traumatic brain injury? Or, are they consistent with a preexisting condition like lupus, dementia, attention deficit disorder, or schizophre- nia? We can determine with a high probability—more than 95 percent—whether the disorder is due to one or the other. 14 Connecticut Lawyer March 2006 Visit www.ctbar.org young woman was referred orders such as Alzheimer’s disease, lupus, a to us by her attorney, who head injury, or multiple sclerosis. wanted to prove that his QEEG provides a digital reading from client’s dysexecutive syn- the scalp based on electrical patterns of the drome—a cognitive disorder cortex, which measures cortical electrical Amarked by a limited ability to problem activity or brainwaves. It can help deter- solve, retrieve, and organize information, mine whether a cognitive injury is due to which impaired her ability to function both trauma or some preexisting neurological or at work and home—was the result of the psychiatric illness by taking the EEG infor- mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) she suf- mation and transforming every little wave fered in a car accident. and wiggle through a computer program The attorney, a savvy litigator, knew that into binary numbers or metrics. These are opposing counsel would readily accept the then run through databases to see what the findings of earlier neuropsychological test- probability of the overlap is with patients ing that revealed a brain disorder, i.e., cor- suffering from a specific disorder. -

Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

SCHIZOPHRENIA SPECTRUM AND OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS Relevant to the content of this educational activity, I do not have any relationships with commercial interest companies to disclose. OBJECTIVES Be able to describe: • How to evaluate a person with psychotic symptoms • The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of late- onset schizophrenia • Evaluation of psychotic symptoms associated with disorders other than schizophrenia • Management of older adult patients with psychotic symptoms TOPICS COVERED • Schizophrenia and Schizophrenia Spectrum Syndromes • Psychotic Symptoms in Delirium and Delusional Disorder • Psychotic Symptoms in Mood Disorder • Psychotic Symptoms in Dementia • Isolated Suspiciousness • Syndromes of Isolated Hallucinations: Charles Bonnet Syndrome • Other Psychotic Disorders • Psychotic Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition • Substance/Medication-Induced Psychotic Disorder PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS • Hallucinations are perceptions without a physical stimulus that can affect any of the 5 sensory modalities (auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, gustatory) • Delusions are fixed, false, idiosyncratic beliefs that can be: ➢ Suspicious (paranoid) ➢ Grandiose ➢ Somatic ➢ Self-blaming ➢ Hopeless EVALUATION OF A PERSON WITH PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS • First evaluate for underlying causes such as delirium, dementia, stroke, Parkinson disease, or substance abuse disorders ➢ Acute onset of altered level of consciousness or inability to sustain attention suggests delirium ➢ Delirium, most often superimposed on an underlying dementia, -

DSM-III-R Revisions in the Dissociative Disorders: an Exploration of Their Derivation and Rationale

DSM-III-R Revisions in the Dissociative Disorders: An Exploration of their Derivation and Rationale Richard.P. Kluft, M.D. Marlene Steinberg, M.D. Robert L. Spitzer, M.D. ABSTRACT The authors describe and explore changes in the dissociative disorders included in the new DSM-III-R. The classification itself was redefined to minimize inadvertant areas of overlap with other classifications. Recent findings have necessitated substan tial revisions of the criteria and text for multiple personality disorder. Ganser's Syndrome, listed as a factitious disorder in DSM III, is reclassified on the basis of recent research as a dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. The examples for dissociative disorder not otherwise specified have been expanded to better accommodate recognized dissociative syndromes that do not fall within the four formally defined dissociative disorders. Several novel diagnostic entities and reclassifications were proposed that were rejected for DSM-III-R because there is insufficient supporting data at this point in time. These proposals identify issues that will require reconsideration for DSM-JV. The Advisory Committee on the Dissociative chronic (3). If it occurs primarily in identity, the Disorders was one of several such committees convened person's customary identity is temporarily forgotten, by the Work Group to Revise DSM -III to review the and a new identity may be assumed or imposed (as in DSM III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) clas Multiple Personality Disorder), or the customary feeling sifications, criteria, and texts in the light of interim of one's own reality is lost and replaced by a feeling of clinical experience and scientific findings, and recom unreality (as in Depersonalization Disorder). -

Alleged Amnesia in Sexual Crime Alexandre Martins Valença1 Alegação De Amnésia Em Crime Sexual

BRIEF COMMUNICATION Cláudia Cristina Studart Leal1 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1416-6127 Alleged amnesia in sexual crime Alexandre Martins Valença1 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5744-2112 Alegação de amnésia em crime sexual DOI: 10.1590/0047-2085000000281 ABSTRACT The current article describes the case of a man who claimed amnesia in relation to a sexual crime he had allegedly committed. Psychiatric examination concluded that the individual was feigning amnesia. Claimed amnesia of a criminal offense is one of the most commonly feigned symptoms in the forensic medical setting. It is thus necessary to rule out organic or psychogenic causes of amnesia and always consider feigned amnesia in the presence of psychopathological alterations that do not reflect classi- cally known syndromes. KEYWORDS Crime, amnesia, simulation, criminal liability. RESUMO O presente artigo descreve o caso de um homem que alegou amnésia ao fato da denúncia de cri- me sexual que lhe foi imputada. A perícia psiquiátrica concluiu tratar-se de simulação. A alegação de amnésia da ofensa criminosa é um dos sintomas mais comumente simulados no ambiente pericial. Portanto, devem-se excluir as causas de amnésia orgânica ou psicogênica e sempre considerar a am- nésia simulada na presença de alterações psicopatológicas que não configuram quadros sindrômicos classicamente conhecidos. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Crime, amnésia, simulação, responsabilidade penal. Received in: Mar/13/2020. Approved in: Jun/6/2020 1 Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Institute of Psychiatry (IPUB), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. Address for correspondence: Cláudia Cristina Studart Leal. Av. Venceslau Brás, 71, Praia Vermelha – 22290-140 – Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. -

Amnestic Syndrome Last Updated: May 8, 2019 DEFINITIONS, CLINICAL FEATURES

AMNESIAS S6 (1) Amnestic syndrome Last updated: May 8, 2019 DEFINITIONS, CLINICAL FEATURES ........................................................................................................ 1 ANATOMINIS SUBSTRATAS ..................................................................................................................... 2 ETIOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................... 3 DIAGNOSIS ............................................................................................................................................. 3 TREATMENT ........................................................................................................................................... 5 DBS ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 AGE-ASSOCIATED MEMORY IMPAIRMENT .............................................................................................. 6 KORSAKOFF SYNDROME (S. PSYCHOSIS) ................................................................................................. 6 TRANSIENT GLOBAL AMNESIA................................................................................................................ 7 FACTITIOUS (PSYCHOGENIC) AMNESIA .................................................................................................. 8 DEFINITIONS, CLINICAL FEATURES AMNESIA - syndrome with disturbance