DSM-III-R Revisions in the Dissociative Disorders: an Exploration of Their Derivation and Rationale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paranoid – Suspicious; Argumentative; Paranoid; Continually on The

Disorder Gathering 34, 36, 49 Answer Keys A N S W E R K E Y, Disorder Gathering 34 1. Avital Agoraphobia – 2. Ewelina Alcoholism – 3. Martyna Anorexia – 4. Clarissa Bipolar Personality Disorder –. 5. Lysette Bulimia – 6. Kev, Annabelle Co-Dependant Relationship – 7. Archer Cognitive Distortions / all-of-nothing thinking (Splitting) – 8. Josephine Cognitive Distortions / Mental Filter – 9. Mendel Cognitive Distortions / Disqualifying the Positive – 10. Melvira Cognitive Disorder / Labeling and Mislabeling – 11. Liat Cognitive Disorder / Personalization – 12. Noa Cognitive Disorder / Narcissistic Rage – 13. Regev Delusional Disorder – 14. Connor Dependant Relationship – 15. Moira Dissociative Amnesia / Psychogenic Amnesia – (*Jason Bourne character) 16. Eylam Dissociative Fugue / Psychogenic Fugue – 17. Amit Dissociative Identity Disorder / Multiple Personality Disorder – 18. Liam Echolalia – 19. Dax Factitous Disorder – 20. Lorna Neurotic Fear of the Future – 21. Ciaran Ganser Syndrome – 22. Jean-Pierre Korsakoff’s Syndrome – 23. Ivor Neurotic Paranoia – 24. Tucker Persecutory Delusions / Querulant Delusions – 25. Lewis Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder – 26. Abdul Proprioception – 27. Alisa Repressed Memories – 28. Kirk Schizophrenia – 29. Trevor Self-Victimization – 30. Jerome Shame-based Personality – 31. Aimee Stockholm Syndrome – 32. Delphine Taijin kyofusho (Japanese culture-specific syndrome) – 33. Lyndon Tourette’s Syndrome – 34. Adar Social phobias – A N S W E R K E Y, Disorder Gathering 36 Adjustment Disorder – BERKELEY Apotemnophilia -

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

Diagnostic and Management Guidelines for Mental Disorders in Primary Care

Diagnostic and Management Guidelines for Mental Disorders in Primary Care ICD-10 Chapter V ~rimary Care Version Published on behalf of the World Health Organization by Hogrefe & Huber Publishers World Health Organization Hogrefe & Huber Publishers Seattle . Toronto· Bern· Gottingen Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available via the Library of Congress Marc Database under the LC Catalog Card Number 96-77394 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Diagnostic and management guidelines for mental disorders in primary care: ICD-lO chapter V, primary care version ISBN 0-88937-148-2 1. Mental illness - Classification. 2. Mental illness - Diagnosis. 3. Mental illness - Treatment. I. World Health Organization. 11. Title: ICD-ten chapter V, primary care version. RC454.128 1996 616.89 C96-931353-5 The correct citation for this book should be as follows: Diagnostic and Management Guidelines for Mental Disorders in Primary Care: ICD-lO Chapter V Primary Care Version. WHO/Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, Gottingen, Germany, 1996. © Copyright 1996 by World Health Organization All rights reserved. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers USA: P.O. Box 2487, Kirkland, WA 98083-2487 Phone (206) 820-1500, Fax (206) 823-8324 CANADA: 12 Bruce Park Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2S3 Phone (416) 482-6339 SWITZERLAND: Langgass-Strasse 76, CH-3000 Bern 9 Phone (031) 300-4500, Fax (031) 300-4590 GERMANY: Rohnsweg 25,0-37085 Gottingen Phone (0551) 49609-0, Fax (0551) 49609-88 No part of this book may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without the written permission from the copyright holder. -

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY in KOŠICE Dissociative Amnesia: a Clinical and Theoretical Reconsideration DEGREE THESIS

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Košice 2017 PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE FIRST DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHIATRY Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Thesis supervisor: Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Košice 2017 Analytical sheet Author Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão Thesis title Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Language of the thesis English Type of thesis Degree thesis Number of pages 89 Academic degree M.D. University Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice Faculty Faculty of Medicine Department/Institute Department of Psychiatry Study branch General Medicine Study programme General Medicine City Košice Thesis supervisor Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Date of submission 06/2017 Date of defence 09/2017 Key words Dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, dissociative identity disorder Thesis title in the Disociatívna amnézia: klinické a teoretické prehodnotenie Slovak language Key words in the Disociatívna amnézia, disociatívna fuga, disociatívna porucha identity Slovak language Abstract in the English language Dissociative amnesia is a one of the most intriguing, misdiagnosed conditions in the psychiatric world. Dissociative amnesia is related to other dissociative disorders, such as dissociative identity disorder and dissociative fugue. Its clinical features are known -

The Diagnosis of Ganser Syndrome in the Practice of Forensic Psychology

Drob, S., & Meehan, K. (2000). The diagnosis of Ganser Syndrome in the practice of forensic psychology. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 18(3), 37-62. The Diagnosis of Ganser Syndrome in the Practice of Forensic Psychology Sanford L. Drob, Ph.D. and Kevin Meehan Forensic Psychiatry Service, New York University—Bellevue Medical Center The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Robert H. Berger, M.D., Alexander Bardey, M.D., David Trachtenberg, M.D., Ruth Jonas, Ph.D. and Arthur Zitrin, M.D. for their assistance in helping to formulate the case example presented herein. 1 Drob, S., & Meehan, K. (2000). The diagnosis of Ganser Syndrome in the practice of forensic psychology. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 18(3), 37-62. Abstract Ganser syndrome, which is briefly described as a Dissociative Disorder NOS in the DSM-IV is a poorly understood and often overlooked clinical phenomenon. The authors review the literature on Ganser syndrome, offer proposed screening criteria, and propose a model for distinguishing Ganser syndrome from malingering. The “SHAM LIDO” model urges clinicians to pay close attention to Subtle symptoms, History of dissociation, Abuse in childhood, Motivation to malinger, Lying and manipulation, Injury to the brain, Diagnostic testing, and longitudinal Observations, in the assessment of forensic cases that present with approximate answers, pseudo-dementia, and absurd psychiatric symptoms. A case example illustrating the application of this model is provided. 2 Drob, S., & Meehan, K. (2000). The diagnosis of Ganser Syndrome in the practice of forensic psychology. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 18(3), 37-62. In this paper we propose a model for diagnosing the Ganser syndrome and related dissociative/hysterical presentations and evaluating this syndrome in connection with forensic assessments. -

Paranoid Or Bizarre Delusions, Or Disorganized Speech and Thinking, and It Is Accompanied by Significant Social Or Occupational Dysfunction

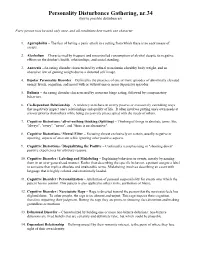

Personality Disturbance Gathering, nr.34 (key to possible disturbances) Every person may be used only once, and all conditions best match one character. 1. Agoraphobia – The fear of having a panic attack in a setting from which there is no easy means of escape. 2. Alcoholism – Characterized by frequent and uncontrolled consumption of alcohol despite its negative effects on the drinker's health, relationships, and social standing. 3. Anorexia –An eating disorder characterized by refusal to maintain a healthy body weight, and an obsessive fear of gaining weight due to a distorted self image. 4. Bipolar Personality Disorder – Defined by the presence of one or more episodes of abnormally elevated energy levels, cognition, and mood with or without one or more depressive episodes. 5. Bulimia – An eating disorder characterized by recurrent binge eating, followed by compensatory behaviors. 6. Co-Dependant Relationship – A tendency to behave in overly passive or excessively caretaking ways that negatively impact one's relationships and quality of life. It often involves putting one's own needs at a lower priority than others while being excessively preoccupied with the needs of others. 7. Cognitive Distortions / all-of-nothing thinking (Splitting) – Thinking of things in absolute terms, like "always", "every", "never", and "there is no alternative". 8. Cognitive Distortions / Mental Filter – Focusing almost exclusively on certain, usually negative or upsetting, aspects of an event while ignoring other positive aspects. 9. Cognitive Distortions / Disqualifying the Positive – Continually reemphasizing or "shooting down" positive experiences for arbitrary reasons. 10. Cognitive Disorder / Labeling and Mislabeling – Explaining behaviors or events, merely by naming them in an over-generalized manner. -

Ganser's Syndrome : a Report of Two Unusual Presentations

Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 2001, 43 (3),273-275 GANSER'S SYNDROME : A REPORT OF TWO UNUSUAL PRESENTATIONS HARPREET S. DUGGAL, SUBHASH C. GUPTA, SOUMYA BASU, VINOD K. SINHA & CHRISTODAY. R. J. KHESS ABSTRACT Ganser's syndrome is a rare and controversial entity in psychiatric nosology. We report two cases ofGS, one developing in a 12-year-old boy, which had their onset during an episode of mania. After recovery from Ganser's syndrome, these cases were followed-up for two and five years, respectively. Interestingly both these patients evolved into bipolar disorder with one patient showing recurrence of Ganser symptoms with each subsequent episode. The importance of following-up and relevance of affective symptoms in GS is discussed. ' Keywords: Ganser's syndrome, bipolar disorder, child, follow-up. Perhaps no other psychiatric syndrome is CASE REPORT shrouded in so much confusion and controversy as regards to its nosological status and Case-1 : Patient, PK, a 12-year-old boy studying mechanism as is Ganser's syndrome (GS). It has in eighth standard, presented to us with complaints been viewed as a form of malingering, a variety of of acute onset and 15 days duration characterized histrionic personality disorder, a psychotic illness, by failure to recognize family members, tearfulness, a dissociative disorder, a factitious disorder, and irritability, talkativeness, reading and writing in an organic illness (Lishman, 1998). The present opposite direction, hearing voices and seeing classificatory systems classify it under images. Family history and past history were dissociative disorders. Though GS has been unremarkable. Physical examination was within reported to occur with other comorbid conditions normal limits. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders : Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines

ICD-10 ThelCD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines | World Health Organization I Geneva I 1992 Reprinted 1993, 1994, 1995, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders : clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. 1.Mental disorders — classification 2.Mental disorders — diagnosis ISBN 92 4 154422 8 (NLM Classification: WM 15) © World Health Organization 1992 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications — whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution — should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

93-99 Case Report Ganser Syndrome in Adolescent Male

93 J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2018; 14(1):93-99 Case Report Ganser syndrome in adolescent male: A rare case report Supriya Agarwal, Abhinav Dhami, Malvika Dahuja, Sandeep Choudhary Address for correspondence: Supriya Agarwal, Dept. of Psychiatry, Chhatrapati Shivaji Subharti Hospital, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Subharti Medical College, Swami Vivekanand Subharti University, Meerut, U.P., India. [email protected] Abstract Ganser syndrome, a rare variation of dissociative disorder, is characterised by approximate answers to real questions, dulling of consciousness, hysterical neurological changes and pseudo-hallucinations. First described by the psychiatrist-Sigbert Ganser in 1898 in prison inmates, it has acquired the synonym 'prison psychosis'; rarely, it has been described in normal population in various age groups. Since its description, this syndrome has been a controversial diagnosis with uncertain management strategies. In this paper we discuss the presentation and management of Ganser syndrome in an Indian adolescent male. Key words- Adolescence, Ganser Syndrome, Dissociative Disorder Introduction Ganser syndrome is a rare variation of dissociative disorder named after Sigbert Josef Maria Ganser, who characterized it in 1898 as a hysterical twilight state. Cocores et al [1] and Giannini & Black [2] wrote about this disorder in literature way back in late 1970s and 1980s. According to Andersen et al [3], it is also known by multiple other names like Balderash Syndrome, Prison psychosis etc. According to Giannini & Black [2], individuals of all backgrounds have been reported with the disorder, but the average age of those with Ganser Syndrome is 32 years. Miller et al [4] state that the disorder is apparently most 94 common in men and prisoners, although prevalence data and familial patterns are not established and still remain controversial, and it is rarely common in children. -

Cognitive Disorders: a Perspective from the Neurology Clinic

This is a repository copy of Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/93827/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Stone, J., Pal, S., Blackburn, D. et al. (3 more authors) (2015) Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 49 (s1). S5-S17. ISSN 1387-2877 https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150430 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Functional (psychogenic) memory disorders - a perspective from the neurology clinic Jon Stone1 , Suvankar Pal1,2, Daniel Blackburn2, Markus Reuber2, Parvez Thekkumpurath1, Alan Carson1,3 1Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Crewe Rd, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, UK. -

Malingering (DSM-IV-TR #V65.2)

Malingering (DSM-IV-TR #V65.2) Malingerers intentionally and purposefully feign illness to Confused and disoriented as these patients may appear, they achieve some recognizable goal. They may wish to get drugs, are nevertheless capable of finding their way around the jail win a lawsuit, or avoid work or military service. At times the and of doing those things that are necessary to maintain a deceit of the malingerer may be readily apparent to the minimum level of comfort in jail or prison. All in all, these physician; however, medically sophisticated malingerers patients act out the “popular” conception of insanity to have been known to deceive even the best of diagnosticians. escape trial or punishment. Once the trial has occurred or punishment has been imposed, the “insanity” often clears up quickly. Some malingerers may limit their dissembling simply to voicing complaints. Others may take advantage of an actual illness and embellish and exaggerate their symptoms out of One should be sure not to misdiagnose a case of all proportion to the severity of the underlying disease. Some schizophrenia as Ganser’s syndrome. At times patients with may go so far as to actually stage an accident, and then go on schizophrenia may not have their antipsychotics continued to exaggerate any symptoms that may subsequently develop. after being jailed and may become floridly psychotic a few Falsification of medical records may also occur. days later. A similar fate may await alcoholics who develop delirium tremens after imprisonment separates them from alcohol. Neurologic, psychiatric, and rheumatic illnesses are often chosen as models.