Amnesia and Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

Does Amnesia Specifically Predict Alzheimer's Pathology?

Does amnesia specifically predict Alzheimer’s pathology? A neuropathological study Maxime Bertoux, Pascaline Cassagnaud, Thibaud Lebouvier, Florence Lebert, Marie Sarazin, Isabelle Le Ber, Bruno Dubois, Brain Bank, Sophie Auriacombe, Didier Hannequin, et al. To cite this version: Maxime Bertoux, Pascaline Cassagnaud, Thibaud Lebouvier, Florence Lebert, Marie Sarazin, et al.. Does amnesia specifically predict Alzheimer’s pathology? A neuropathological study. Neurobiology of Aging, Elsevier, In press. hal-02898941 HAL Id: hal-02898941 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02898941 Submitted on 14 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Amnesia/AD pathology 1 Does amnesia specifically predict Alzheimer’s pathology? A neuropathological study. Maxime Bertoux*1a, Pascaline Cassagnaud*b, Thibaud Lebouvier*c, Florence Leberta, Marie Sarazinde, Isabelle Le Berfg, Bruno Duboisfg, NeuroCEB Brain Bank, Sophie Auriacombeh, Didier Hannequini, David Walloni, Mathieu Ceccaldij, Claude-Alain Mauragek, Vincent Deramecourtc, Florence Pasquiera a Univ Lille, Lille Neuroscience & Cognition (Inserm UMRS1172) Degenerative and vascular cognitive disorders, CHU Lille, Laboratory of Excellence Distalz (Development of Innovative Strategies for a Transdisciplinary approach to ALZheimer’s disease). F-59000, Lille, France.F-59000, Lille, France. b Univ Lille, CHU Lille, Laboratory of Excellence Distalz (Development of Innovative Strategies for a Transdisciplinary approach to ALZheimer’s disease). -

When the Mind Falters: Cognitive Losses in Dementia

T L C When the Mind Falters: Cognitive Losses in Dementia by L Joel Streim, MD T Associate Professor of Psychiatry C Director, Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Program University of Pennsylvania VISN 4 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center Philadelphia VA Medical Center Delaware Valley Geriatric Education Center The goal of this module is to teach direct staff about the syndrome of dementia and its clinical effects on residents. It focuses on the ways that the symptoms of dementia affect persons’ functional ability and behavior. We begin with an overview of the symptoms of cognitive impairment. We continue with a description of the causes, epidemiology, and clinical course (stages) of dementia. We then turn to a closer look at the specific areas of cognitive impairment, and examine how deficits in different areas of cognitive function can interfere with the person’s daily functioning, causing disability. The accompanying videotape illustrates these principles, using the example of a nursing home resident whose cognitive impairment interferes in various ways with her eating behavior and ability to feed herself. 1 T L Objectives C At the end of this module you should be able to: Describe the stages of dementia Distinguish among specific cognitive impairments from dementia L Link specific cognitive impairments with the T disabilities they cause C Give examples of cognitive impairments and disabilities Describe what to do when there is an acute change in cognitive or functional status Delaware Valley Geriatric Education Center At the end of this module you should be able to • Describe the stages of dementia. These are early, middle and late, and we discuss them in more detail. -

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY in KOŠICE Dissociative Amnesia: a Clinical and Theoretical Reconsideration DEGREE THESIS

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Košice 2017 PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE FIRST DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHIATRY Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Thesis supervisor: Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Košice 2017 Analytical sheet Author Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão Thesis title Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Language of the thesis English Type of thesis Degree thesis Number of pages 89 Academic degree M.D. University Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice Faculty Faculty of Medicine Department/Institute Department of Psychiatry Study branch General Medicine Study programme General Medicine City Košice Thesis supervisor Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Date of submission 06/2017 Date of defence 09/2017 Key words Dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, dissociative identity disorder Thesis title in the Disociatívna amnézia: klinické a teoretické prehodnotenie Slovak language Key words in the Disociatívna amnézia, disociatívna fuga, disociatívna porucha identity Slovak language Abstract in the English language Dissociative amnesia is a one of the most intriguing, misdiagnosed conditions in the psychiatric world. Dissociative amnesia is related to other dissociative disorders, such as dissociative identity disorder and dissociative fugue. Its clinical features are known -

Paranoid Or Bizarre Delusions, Or Disorganized Speech and Thinking, and It Is Accompanied by Significant Social Or Occupational Dysfunction

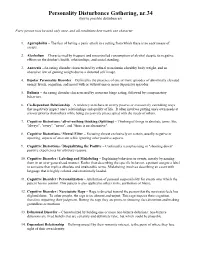

Personality Disturbance Gathering, nr.34 (key to possible disturbances) Every person may be used only once, and all conditions best match one character. 1. Agoraphobia – The fear of having a panic attack in a setting from which there is no easy means of escape. 2. Alcoholism – Characterized by frequent and uncontrolled consumption of alcohol despite its negative effects on the drinker's health, relationships, and social standing. 3. Anorexia –An eating disorder characterized by refusal to maintain a healthy body weight, and an obsessive fear of gaining weight due to a distorted self image. 4. Bipolar Personality Disorder – Defined by the presence of one or more episodes of abnormally elevated energy levels, cognition, and mood with or without one or more depressive episodes. 5. Bulimia – An eating disorder characterized by recurrent binge eating, followed by compensatory behaviors. 6. Co-Dependant Relationship – A tendency to behave in overly passive or excessively caretaking ways that negatively impact one's relationships and quality of life. It often involves putting one's own needs at a lower priority than others while being excessively preoccupied with the needs of others. 7. Cognitive Distortions / all-of-nothing thinking (Splitting) – Thinking of things in absolute terms, like "always", "every", "never", and "there is no alternative". 8. Cognitive Distortions / Mental Filter – Focusing almost exclusively on certain, usually negative or upsetting, aspects of an event while ignoring other positive aspects. 9. Cognitive Distortions / Disqualifying the Positive – Continually reemphasizing or "shooting down" positive experiences for arbitrary reasons. 10. Cognitive Disorder / Labeling and Mislabeling – Explaining behaviors or events, merely by naming them in an over-generalized manner. -

The Three Amnesias

The Three Amnesias Russell M. Bauer, Ph.D. Department of Clinical and Health Psychology College of Public Health and Health Professions Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute University of Florida PO Box 100165 HSC Gainesville, FL 32610-0165 USA Bauer, R.M. (in press). The Three Amnesias. In J. Morgan and J.E. Ricker (Eds.), Textbook of Clinical Neuropsychology. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis/Psychology Press. The Three Amnesias - 2 During the past five decades, our understanding of memory and its disorders has increased dramatically. In 1950, very little was known about the localization of brain lesions causing amnesia. Despite a few clues in earlier literature, it came as a complete surprise in the early 1950’s that bilateral medial temporal resection caused amnesia. The importance of the thalamus in memory was hardly suspected until the 1970’s and the basal forebrain was an area virtually unknown to clinicians before the 1980’s. An animal model of the amnesic syndrome was not developed until the 1970’s. The famous case of Henry M. (H.M.), published by Scoville and Milner (1957), marked the beginning of what has been called the “golden age of memory”. Since that time, experimental analyses of amnesic patients, coupled with meticulous clinical description, pathological analysis, and, more recently, structural and functional imaging, has led to a clearer understanding of the nature and characteristics of the human amnesic syndrome. The amnesic syndrome does not affect all kinds of memory, and, conversely, memory disordered patients without full-blown amnesia (e.g., patients with frontal lesions) may have impairment in those cognitive processes that normally support remembering. -

Cognitive Disorders: a Perspective from the Neurology Clinic

This is a repository copy of Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/93827/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Stone, J., Pal, S., Blackburn, D. et al. (3 more authors) (2015) Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 49 (s1). S5-S17. ISSN 1387-2877 https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150430 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Functional (psychogenic) memory disorders - a perspective from the neurology clinic Jon Stone1 , Suvankar Pal1,2, Daniel Blackburn2, Markus Reuber2, Parvez Thekkumpurath1, Alan Carson1,3 1Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Crewe Rd, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, UK. -

A Neurostructural Biomarker of Dissociative Amnesia: a Hippocampal Study in Dissociative Cambridge.Org/Psm Identity Disorder

Psychological Medicine A neurostructural biomarker of dissociative amnesia: a hippocampal study in dissociative cambridge.org/psm identity disorder 1,2, 3, 4,5,† Original Article Lora I. Dimitrova * , Sophie L. Dean *, Yolanda R. Schlumpf , Eline M. Vissia6,† , Ellert R. S. Nijenhuis5, Vasiliki Chatzi7, Lutz Jäncke4,8, *These authors contributed equally to this 2 9 1 work Dick J. Veltman , Sima Chalavi and Antje A. T. S. Reinders † These authors contributed equally to this 1Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College work London, London, UK; 2Department of Psychiatry, Amsterdam UMC, Location VUmc, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 3Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, Cite this article: Dimitrova LI et al (2021). A 4 neurostructural biomarker of dissociative London, UK; Division of Neuropsychology, Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland; 5 6 amnesia: a hippocampal study in dissociative Clienia Littenheid AG, Private Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Littenheid, Switzerland; Heelzorg, Centre 7 identity disorder. Psychological Medicine 1–9. for Psychotrauma, Zwolle, The Netherlands; Department of Biomedical Engineering, King’s College London, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721002154 London, UK; 8Research Unit for Plasticity and Learning of the Healthy Aging Brain, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland and 9Movement Control and Neuroplasticity Research Group, Department of Movement Sciences, KU Received: 14 September 2020 Leuven, Leuven, Belgium Revised: 12 February 2021 Accepted: 11 May 2021 Abstract Key words: Background. Little is known about the neural correlates of dissociative amnesia, a transdiag- Dissociative experience scale; DES; childhood trauma; CA1; Freesurfer; dissociation nostic symptom mostly present in the dissociative disorders and core characteristic of dis- sociative identity disorder (DID). -

Neurodiversity 10Th Annual Nurturing Developing Minds Conference

Neurodiversity 10th Annual Nurturing Developing Minds Conference Manuel F. Casanova, M.D. SmartState Endowed Chair in Childhood Neurotherapeutics University of South Carolina Greenville Health System Conflict of Interests Neuronetics (TMS platform), Neuronetrix Incorporated, Clearly Present Foundation Pfizer, Eisai, Nycomed Amersham, Aventis Pasteur Limited, Medvantis Medical Service Council of Health Care Advisors for the Gerson Lehrman Goup Royalties: Springer, Nova, Taylor and Francis, John Wiley I am a physician who deals with individuals with neurodevelopmental disabilities and have a grandson with autism. Neurodiversity “A new wave of activists wants to celebrate atypical brain function as a positive identity, not a disability.” New York News and Politics “…neurological (brain wiring) differences, traditionally seen as disadvantages, are really advantages.” Fox and Hounds “What is autism: a devastating developmental disorder, a lifelong disability, or a naturally occurring form of cognitive difference akin to certain forms of genius?” SUPOZA.COM NEURODIVERSITY AND AUTISTIC PRIDE Individual with autism vs. Autistic Individual Control subject vs. Typically developing(TD) subject What message are you sending??? “Why is it that what makes me me, needs to be classified as a disability?” A child under 18 will be considered disabled if he or she has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment or combination of impairments that cause marked and severe functional limitations, that can be expected to cause death or that has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months. Normal variation in the human genome A social category rather than a medical disorder Includes autism, bipolar disorders, and other neurotypes It does not need to be cured ABA is specially pernicioius. -

Dissociative Disorders Types of Dissociative Disorders Dissociative

Dissociative Disorders • Similar to somatoform in some ways • Often not that concerned about memory loss • Often can be seen as form of escape Types of Dissociative Disorders • Depersonalization Disorder • Dissociative Amnesia (Generalized vs. Selective). • Dissociative Fugue • Dissociative Trance Disorder • Dissociative Identity Disorder (formerly Multiple Personality Disorder). Dissociative Disorders Involves sudden and temporary alteration in functions of consciousness Avoids stress and gratifies needs in manner allowing person to deny personal responsibility Escapes from core personality and personality processes Quite rare Dissociative Disorders Dissociative Disorders are typified by alterations in sense of self and reality Characteristic features include a sense of depersonalization or derealization. Dissociative Disorders Depersonalization is when one’s sense of your own reality is altered (your own personality and sense of self may be fragmented). Derealization is best described as when your sense of reality of the external world is altered. The external world feels unreal and unfamiliar Depersonalization •Feelings of detachment or estrangement •External world is perceived as unreal •May have : • Sensory anesthesia • Lack of affective response Depersonalization Characteristics • Feelings that you're an outside observer of your thoughts, feelings, your body or parts of your body —as if you were floating in air above yourself • Feeling like a robot or that you're not in control of your speech or movements • The sense that your -

POST TRAUMATIC AMNESIA SCREENING and MANAGEMENT GUIDELINE Trauma Service Guidelines Title: Post Traumatic Amnesia Screening and Management Developed By: K

TRM 01.01 POST TRAUMATIC AMNESIA SCREENING AND MANAGEMENT GUIDELINE Trauma Service Guidelines Title: Post Traumatic Amnesia Screening and Management Developed by: K. Gumm, T, Taylor, K, Orbons, L, Carey, PTA Working Party Created: Version 1.0, April 2007 Revised by: K. Liersch, K. Gumm, E. Hayes, E. Thompson, K. Henderson & Advisory Committee on Trauma Revised: V 5.0 Jun 2020, V 4.0 Oct 2017, V3.0 Mar 2014, V2.0 Apr 2011 Table of Contents What is Post Traumatic Amnesia (PTA)?........................................................................................................................................................1 Screening Criteria for PTA..............................................................................................................................................................................5 Abbreviated Assessment of MBI using the Abbreviated Westmead PTA Scale (A-WPTAS) ..........................................................................5 Discharging a Patient Home with a Mild Brain Injury ....................................................................................................................................6 Moderate and Severe Brain Injury.................................................................................................................................................................7 Assessment of Moderate and Severe Brain Injury using the Westmead PTA Scale (Westmead)..................................................................7 Management of the patient suffering -

Treating Major Depressive Disorder: a Quick Reference Guide

Treating Major Depressive Disorder A Quick Reference Guide Based on Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition, originally published in October 2010. A guideline watch, summarizing significant developments in the scientific literature since publication of this guideline, may be available. 1 2 Treating Major Depressive Disorder INTRODUCTION Treating Major Depressive Disorder: A Quick Reference Guide is a synopsis of the American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition, Part A of which was originally published in The American Jour- nal of Psychiatry in October 2010 and is available through American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. The psychiatrist using this Quick Refer- ence Guide (QRG) should be familiar with the full-text practice guide- line on which it is based. The QRG is not designed to stand on its own and should be used in conjunction with the full-text practice guide- line. For clarification of a recommendation or for a review of the ev- idence supporting a particular strategy, the psychiatrist will find it helpful to return to the full-text practice guideline. STATEMENT OF INTENT The Practice Guidelines and the Quick Reference Guides are not in- tended to be construed or to serve as a standard of medical care. Standards of medical care are determined on the basis of all clinical data available for an individual patient and are subject to change as scientific knowledge and technology advance and practice patterns evolve. These parameters of practice should be considered guide- lines only. Adherence to them will not ensure a successful outcome for every individual, nor should they be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care aimed at the same results.