The Cognitive Antecedents of Psychosis-Like (Anomalous) Experiences: Variance Within a Stratified Quota Sample of the General Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behavorial Health Department – Primary Care Center and Fireweed Treatment Guidelines for Cognitive Disorders

BEHAVORIAL HEALTH DEPARTMENT – PRIMARY CARE CENTER AND FIREWEED TREATMENT GUIDELINES FOR COGNITIVE DISORDERS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION AND STATEMENT OF INTENT .................................................................................2 DEFINITION OF DISORDER......................................................................................................2 GENERAL GOALS OF TREATMENT ..............................................................................................3 SUMMARY OF 1ST, 2ND AND 3RD LINE TREATMENT ............................................................................3 CLINICAL AND DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUES THAT INFLUENCE TREATMENT PLANNING..........................................3 FLOW DIAGRAM ............................................................................................................. 4 ASSESSMENT.................................................................................................................. 5 PSYCHIATRIC ASSESSMENT ....................................................................................................5 PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTING ......................................................................................................5 SCREENING/SCALES ............................................................................................................5 MODALITIES & TREATMENT MODELS............................................................................. -

Metacognition in Functional Cognitive Disorder

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.24.21259245; this version posted June 25, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title Page Title: Metacognition in Functional Cognitive Disorder Short Running Title: Functional Cognitive Disorder Authors: Rohan Bhome,1,* Andrew McWilliams,2,3,4,* Gary Price5, Norman A Poole6, Robert J Howard7, Stephen M Fleming3,8,9, Jonathan D Huntley7 *These authors contributed equally to this work 1. Dementia Research Centre, University College London, 8-11 Queen Square, London, UK 2. Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London UK. 3. Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London, UK. 4. UCL Institute of Child Health, Great Ormond Street, London, UK. 5. National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, UK 6. South West London and St George's Mental Health NHS Trust, London, UK 7. Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK 8. Max Planck University College London Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research, London, UK 9. Department of Experimental Psychology, University College London, London, UK Correspondence to: Dr Rohan Bhome, Dementia Research Centre, University College London, 8-11 Queen Square, WC1N 3AR, [email protected] Word count: 4176 words 4 tables, 3 figures NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

Cognitive Disorders: a Perspective from the Neurology Clinic

This is a repository copy of Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/93827/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Stone, J., Pal, S., Blackburn, D. et al. (3 more authors) (2015) Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 49 (s1). S5-S17. ISSN 1387-2877 https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150430 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Functional (psychogenic) memory disorders - a perspective from the neurology clinic Jon Stone1 , Suvankar Pal1,2, Daniel Blackburn2, Markus Reuber2, Parvez Thekkumpurath1, Alan Carson1,3 1Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Crewe Rd, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, UK. -

Dementia: Definitions, Description and Assessments

Dementia: Definitions, Description and Assessments Beatrice Groene, MD October 24, 2019 Today’s learning objectives are: 1. To better understand normal cognitive function 2. To recognize differences between normal aging, Minor Cognitive Disorder, Major Cognitive Disorder and Dementia 3. To identify conditions often confused with dementia 4. To understand the specific information used in assessing a patient for dementia Cognitive Function Cognitive function is how we acquire and process information. • Attention - Being able to stay focused on something despite distractions, and long enough to get the needed information • Perception - The information we take in with our 5 senses • Memory- Includes short term, intermediate and long term • Executive function- Judgement and decision-making Executive Function IS VITAL TO SAFETY/DANGER AWARENESS • How we make decisions, solve problems and use judgment • The ability to make any plan (however simple) and follow an appropriate sequence of action • Response to feedback and error correction • Socially appropriate behavior What are normal changes in brain function seen with aging? The MOST COMMON symptom of a normally aging brain is SLOWER processing of information • An aging brain can still process NEW information, but it’s slower than it used to be • An aging brain becomes less efficient and is forgetful for general things like names and numbers • Because of the forgetfulness, a normally aging brain has a greater need for information to be IN CONTEXT in order to be retrieved On the positive side… • A normal aging brain retains general knowledge and vocabulary • Retains memory for relevant, well-learned material • Retains recall of past personal or historic events Normal aging adults without dementia will still have decreasing brain function • Only about 4% of normal adults between ages 65-69 will have moderate to severe memory problems (require some support) • But that number increases to 36% by age 85 • Even without dementia, the risk for memory problems increases with age. -

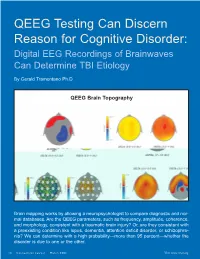

QEEG Testing Can Discern Reason for Cognitive Disorder: Digital EEG Recordings of Brainwaves Can Determine TBI Etiology

QEEG Testing Can Discern Reason for Cognitive Disorder: Digital EEG Recordings of Brainwaves Can Determine TBI Etiology By Gerald Tramontano Ph.D. QEEG Brain Topography Brain mapping works by allowing a neuropsychologist to compare diagnostic and nor- mal databases. Are the QEEG parameters, such as frequency, amplitude, coherence, and morphology, consistent with a traumatic brain injury? Or, are they consistent with a preexisting condition like lupus, dementia, attention deficit disorder, or schizophre- nia? We can determine with a high probability—more than 95 percent—whether the disorder is due to one or the other. 14 Connecticut Lawyer March 2006 Visit www.ctbar.org young woman was referred orders such as Alzheimer’s disease, lupus, a to us by her attorney, who head injury, or multiple sclerosis. wanted to prove that his QEEG provides a digital reading from client’s dysexecutive syn- the scalp based on electrical patterns of the drome—a cognitive disorder cortex, which measures cortical electrical Amarked by a limited ability to problem activity or brainwaves. It can help deter- solve, retrieve, and organize information, mine whether a cognitive injury is due to which impaired her ability to function both trauma or some preexisting neurological or at work and home—was the result of the psychiatric illness by taking the EEG infor- mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) she suf- mation and transforming every little wave fered in a car accident. and wiggle through a computer program The attorney, a savvy litigator, knew that into binary numbers or metrics. These are opposing counsel would readily accept the then run through databases to see what the findings of earlier neuropsychological test- probability of the overlap is with patients ing that revealed a brain disorder, i.e., cor- suffering from a specific disorder. -

Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

SCHIZOPHRENIA SPECTRUM AND OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS Relevant to the content of this educational activity, I do not have any relationships with commercial interest companies to disclose. OBJECTIVES Be able to describe: • How to evaluate a person with psychotic symptoms • The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of late- onset schizophrenia • Evaluation of psychotic symptoms associated with disorders other than schizophrenia • Management of older adult patients with psychotic symptoms TOPICS COVERED • Schizophrenia and Schizophrenia Spectrum Syndromes • Psychotic Symptoms in Delirium and Delusional Disorder • Psychotic Symptoms in Mood Disorder • Psychotic Symptoms in Dementia • Isolated Suspiciousness • Syndromes of Isolated Hallucinations: Charles Bonnet Syndrome • Other Psychotic Disorders • Psychotic Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition • Substance/Medication-Induced Psychotic Disorder PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS • Hallucinations are perceptions without a physical stimulus that can affect any of the 5 sensory modalities (auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, gustatory) • Delusions are fixed, false, idiosyncratic beliefs that can be: ➢ Suspicious (paranoid) ➢ Grandiose ➢ Somatic ➢ Self-blaming ➢ Hopeless EVALUATION OF A PERSON WITH PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS • First evaluate for underlying causes such as delirium, dementia, stroke, Parkinson disease, or substance abuse disorders ➢ Acute onset of altered level of consciousness or inability to sustain attention suggests delirium ➢ Delirium, most often superimposed on an underlying dementia, -

Cognitive Disorders Anita Amelia Thompson Heisterman

CHAPTER 31 Cognitive Disorders Anita Amelia Thompson Heisterman key terms learning objectives agnosia On completion of this chapter, you should be able to accomplish aphasia the following: apraxia 1. Define the term cognitive mental disorder. cognitive mental disorders confabulation 2. Discuss the incidence and significance of cognitive disorders. delirium 3. Identify clinical features or behaviors associated with cognitive dementia disorders. sundowning 4. Compare possible etiologies of various cognitive disorders, especially Alzheimer’s disease. 5. Explain the continuum of care and interdisciplinary treatment/ management for clients and families dealing with cognitive disorders. 6. Discuss common interventions for cognitive disorders. 7. Apply the steps of the nursing process to care for clients with cognitive disorders. UNIT 652 six Psychiatric Disorders ognitive mental disorders are characterized by a in a few days to weeks. In contrast, dementia results from C disruption of or deficit in cognitive function, which primary brain pathology that usually is irreversible, chronic, encompasses orientation, attention, memory, vocabulary, cal- and progressive. Prognosis with dementia depends on whether culation ability, and abstract thinking (see Chap. 10). Specific a cause can be identified and reversed. For example, prompt categories delineated by the American Psychiatric Associa- oxygen treatment for dementia stemming from hypoxia can tion (APA, 2000) include the following: prevent further damage. A comparison of the characteristics of delirium versus dementia is shown in TABLE 31.1. 1. Delirium, dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive With most cognitive disorders, the brain is temporarily disorders or permanently compromised. Usual consequences include 2. Mental disorders resulting from a general medical disturbed perceptions, delusions, paranoia, and aggressive condition (see Chap. -

Mild Cognitive Impairment As an Early Landmark in Huntington's Disease

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 07 July 2021 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.678652 Mild Cognitive Impairment as an Early Landmark in Huntington’s Disease Ying Zhang 1, Junyi Zhou 2, Carissa R. Gehl 3, Jeffrey D. Long 3,4, Hans Johnson 3,5, Vincent A. Magnotta 3,6, Daniel Sewell 4, Kathleen Shannon 7 and Jane S. Paulsen 7* 1 Department of Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, United States, 2 Department of Biostatistics, Indiana University Fairbanks School of Public Health, Indianapolis, IN, United States, 3 Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States, 4 Department of Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States, 5 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States, 6 Department of Radiology, College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa, City, IA, United States, 7 Department of Neurology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, United States As one of the clinical triad in Huntington’s disease (HD), cognitive impairment has not Edited by: been widely accepted as a disease stage indicator in HD literature. This work aims to Frederic Sampedro, study cognitive impairment thoroughly for prodromal HD individuals with the data from Sant Pau Institute for Biomedical a 12-year observational study to determine whether Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) Research, Spain in HD gene-mutation carriers is a defensible indicator of early disease. Prodromal HD Reviewed by: Arushi Gahlot Saini, gene-mutation carriers evaluated annually at one of 32 worldwide sites from September Post Graduate Institute of Medical 2002 to April 2014 were evaluated for MCI in six cognitive domains. -

DSM-5 Changes in Intellectual Disability & Learning Disabilities

+ DSM-5 changes in Intellectual Disability & Learning Disabilities Member of DSM-5 Work Group on ADHD & cross-appointed to Neurodevelopmental Disorders Work Group (for SLD) Professor Emerita, University of Toronto, & Senior Scientist, The Hospital for Sick Children , Toronto, CANADA + Presenter Disclosure Speaker: Rosemary Tannock, PhD Relationships with commercial interests: Grants/Research Support: None/ Cogmed; Purdue Pharma Speakers Bureau/Honoraria: None/ Shire; Janssen-Ortho Consulting Fees: Biomed Central (publisher) Editors Advisory Group Other: Royalties: Springer, as Co-Editor of book (Behavioral Neuroscience of ADHD and its Treatment, 2011) Member DSM-5 Workgroup on ADHD, & liaison member to Neurodevelopmental Disorders workgroup (for Learning Disorders) Member International Steering Committee for WHO International Classification of Functioning (ICF)-Core Set for ADHD Affiliate member WHO ICD-11 Specific Learning Disorders subcommittee 3 + What is the DSM? The DSM – Diagnostic & Statistical Manual - serves as a universal authority for psychiatric diagnosis in North America, South America, Australia, and many other European countries. The Manual specifies the diagnostic criteria for each recognized mental health disorder, and so provides a systematic & reliable approach to diagnosis Treatment recommendations, as well as payment by health care providers, are often determined by DSM classifications, so this tool has significant practical importance….. 4 + Why is the DSM-5 important? The Newfoundland & Labrador Department -

Very Mild Cognitive Decline 3AE1.00

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Cognitive Decline Read term Read code Medcode Cognitive decline 28E..00 7674 GDS level 2 - very mild cognitive decline 3AE1.00 65856 GDS level 3 - mild cognitive decline 3AE2.00 60263 GDS level 4 - moderate cognitive decline 3AE3.00 60726 GDS level 5 - moderately severe cognitive decline 3AE4.00 70057 GDS level 6 - severe cognitive decline 3AE5.00 94717 GDS level 7 - very severe cognitive decline 3AE6.00 72520 [X]Mild cognitive disorder Eu05700 11936 [X]Oth & unspec symptom/sign involv cognit funct/awareness Ryu5100 52939 Health of the Nation Outcome Scale item 4 - cognitive probl ZRLfE00 35194 Impaired cognition Z7C1.00 10822 Cognitive function observations Z7C..00 18906 Cognitive Screening Tests Read term Read code Medcode Cognitive assessment 311B.00 95853 GPCOG - general practitioner assessment of cognition 38Dv.00 101074 GPCOG (GP assessment of cognition) patient examination 38Dv000 103076 GPCOG (GP assessment of cognition) informant interview 38Dv100 101710 Six item cognitive impairment test 3AD3.00 35305 Cognitions questionnaire ZR3a.00 36650 Cognitive failures questionnaire ZR3b.00 66080 Microcog - assessment of cognitive function ZRa2.00 22257 Neurobehavioural cognitive status examination ZRaY.00 42059 Rancho scale - levels of cognitive functioning ZRd..00 92756 Recognition memory test ZRh6.00 96881 Ford E, et al. BMJ -

Clinical Presentation and Neuropsychological Profiles of Functional Cognitive

Clinical presentation and neuropsychological profiles of Functional Cognitive Disorder patients with and without co-morbid depression Title page Title: Clinical presentation and neuropsychological profiles of Functional Cognitive Disorder patients with and without co-morbid depression. First author: Rohan Bhome, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK. 2nd author: Jonathan D Huntley, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK 3rd author: Gary Price, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, UK Last author: Robert J Howard, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK Corresponding author: Rohan Bhome, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK. [email protected] Word count: 4592 including references Abstract Introduction: Functional Cognitive Disorder (FCD) is poorly understood. We sought to better characterise FCD in order to inform future diagnostic criteria and evidence based treatments. Additionally, we compared FCD patients with and without co-morbid depression, including their neuropsychological profiles, to determine whether these two disorders are distinct. Methods: 47 FCD patients (55% female, mean age: 52 years) attending a tertiary neuropsychiatric clinic over a one year period were included. We evaluated sociodemographic characteristics and clinical features including presentation, medications, the presence and nature of co-morbid psychiatric or physical illnesses, and the results of neuropsychometric testing. Results: 23/47 (49%) patients had co-morbid depression. Six had cognitive difficulties greater than expected from their co-morbid conditions suggesting ‘functional overlay’. 34 patients had formal neuropsychological testing; 12 demonstrated less than full subjective effort. 16/22 (73%) of the remaining patients had non-specific cognitive impairment in at least one domain. There were no significant differences between those with and without co- morbid depression.