Witch-Hunting’ in India? Do We Need Special Laws?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papers of Beatrice Mary Blackwood (1889–1975) Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

PAPERS OF BEATRICE MARY BLACKWOOD (1889–1975) PITT RIVERS MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Compiled by B. Asbury and M. Peckett, 2013-15 Box 1 Correspondence A-D Envelope A (Box 1) 1. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 20 May 1955. Summary: Acknowledging receipt of the Pitt Rivers Report for 1954. “The Museum as an institution seems beset with more difficulties than any other.” Giving details of the developing organisation of the Vancouver Museum and its index card system. Asking for a copy of Mr Bradford’s BBC talk on the “Lost Continent of Atlantis”. Notification that Mr Menzies’ health has meant he cannot return to work at the Museum. 2pp. 2. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 20 July 1955. Summary: Thanks for the “Lost Continent of Atlantis” information. The two Museums have similar indexing problems. Excavations have been resumed at the Great Fraser Midden at Marpole under Dr Borden, who has dated the site to 50 AD using Carbon-14 samples. 2pp. 3. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 12 June 1957. Summary: Acknowledging the Pitt Rivers Museum Annual Report. News of Mr Menzies and his health. The Vancouver Museum is expanding into enlarged premises. “Until now, the City Museum has truly been a cultural orphan.” 1pp. 4. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 16 June 1959. Summary: Acknowledging the Pitt Rivers Museum Annual Report. News of Vancouver Museum developments. -

What Happens When You Die? from the Smallest to the Greatest, from the Richest to the Poorest, Everyone Eventually Dies

The Real Truth A MAGAZINE RESTORING PLAIN UNDERSTANDING This article was printed from www.realtruth.org. ARTICLE FROM JULY - AUGUST 2006 ISSUE What Happens When You Die? From the smallest to the greatest, from the richest to the poorest, everyone eventually dies. But what happens after death? Can you know for sure? BY KEVIN D. DENEE enjamin Franklin wrote, “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Every minute on earth, B 108 people die. Ultimately, everyone dies. It is not a matter of if, but when. Sadly, and due to a wide variety of reasons and circumstances, some seek death, considering it the only solution. Others try to delay the inevitable through good health. Still others tragically lose their lives through time and chance. Sometimes disease or other illnesses bring a death sentence, leaving the person with nothing to do but wait for the end. Many view the end of their lives with uneasiness. They ponder, “What’s next?”— “Will I live again?”—“Is this it?”—“Will I ever see my loved ones again?”—“Where am I going after this life?” Photo: KRT In contrast, others view death with fear of the unknown. Some fear the process and the suffering that may accompany death. Others, racked with guilt, have a different type of fear—fear that they will burn forever in “hell fire.” Whatever the viewpoint, feelings or circumstances of one’s life—ultimately, life ends. Because of this unavoidable reality, every person at some point in his or her life thinks about the subject of death. -

Folk-Lore Record

$\u 4*Ht-Jta $uk% FOR COLLECTING AND PRINTING RELICS OF POPULAR ANTIQUITIES, &c. ESTABLISHED IN THE YEAR MDCCCLXXVIII. PUBLICATIONS OP THE FOLK-LORE SOCIETY. I. ik dfdl-Jfoq jtot^g. PRESIDENT. THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL OF VERULAM, F.R.G.S. COUNCIL. JAMES BRITTEN, F.L.S. PROFESSOR MAX MULLER,M.A. HENRY C. COOTE, F.S.A. F. OUVRY, F.S.A. SIR W. R. DRAKE, F.S.A. W. R. S. RALSTON, M.A. G. LAURENCE GOMME. EDWARD SOLLY, F.R.S. F.S.A. HENRY HILL, F.S.A. WILLIAM J. THOMS, F.S.A. A. LANG, M.A. EDWARD B. TYLOR, LL.D. DIRECTOR.—WILLIAM J. THOMS, F.S.A. TREASURER.—SIR WILLIAM R. DRAKE, F.S.A. HONORARY SECRETARY.—G. LAURENCE GOMME, Castelnau, Barnes, S.W. AUDITORS.—E. HAILSTONE, ESQ. F.S.A. JOHN TOLHURST, ESQ. BANKERS.—UNION BANK OF LONDON, CHARING CROSS BRANCH. LIST OF MEMBERS. Mrs. Adams, Manor House, Staines. George H. Adshead, Esq., 9, Strawberry Terrace, Pendleton. Major- General Stewart Allan, Richmond. William Andrews, Esq., 10, Colonial Street, Hull. George L. Apperson, Esq., The Common, Wimbledon. Mrs. Arnott, Milne Lodge, Sutton, Surrey. William E. A. Axon, Esq., Bank Cottage, Barton-on-Irwell. James Backhouse, Esq., West Bank, York. Jonathan E. Backhouse, Esq., Bank, Darlington. James Bain, Esq., 1, Haymarket, S.W. Alexander Band, Esq., 251, Great Western Road, Glasgow. J. Davies Barnett, Esq.. 28, Victoria Street, Montreal, Canada. J. Bawden, Esq., Kingstou, Canada. Charles E. Baylcy, Esq., West Bromwich. The Earl Beauchamp. Miss Bell, Borovere, Alton, Hants. Isaac Binns, Esq., F.R.Hist.S., Batley, Yorkshire. -

Read About It…: Учебно-Методическое Пособие Для Сту

Федеральное агентство по образованию УДК 81.2 ББК 81.2Англ.я7 Омский государственный университет им. Ф.М. Достоевского R30 Рекомендовано к изданию редакционно-издательским советом ОмГУ Рецензенты: ст. преподаватель каф. иностранных языков ОмГУ С.Р. Оленева; ст. преподаватель каф. иностранных языков ОмГУ, канд. пед. наук Ж.В. Лихачева R30 Read about It…: Учебно-методическое пособие для сту- дентов факультета «Теология и мировые культуры» / Сост. М.Х. Рахимбергенова. – Омск: Изд-во ОмГУ, 2006. – 92 с. ISBN 5-7779-0675-3 Пособие ставит своей целью развить навыки англоязычного об- READ ABOUT IT… щения, научить беседовать на различные темы, касающиеся религии. Включены аутентичные тексты современной зарубежной периоди- Учебно-методическое пособие ки, художественной литературы, сайтов Интернета, представляющие собой широкий спектр литературных произведений начиная с древ- (для студентов факультета «Теология и мировые культуры») неегипетских мифов и заканчивая историческим романом. Может быть использовано в первую очередь для самостоя- тельной работы, но не исключает работы в аудитории. Для студентов I, II курсов дневного и вечернего отделений фа- культета «Теология и мировые культуры». УДК 81.2 ББК 81.2Англ.я7 Изд-во Омск ISBN 5-7779-0675-3 © Омский госуниверситет, 2006 ОмГУ 2006 2 СОДЕРЖАНИЕ ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ Предисловие ................................................................................................... 4 Данное учебно-методическое пособие предназначено для сту- Text I. Black Cats and Broken Mirrors........................................................ -

Witch Branding

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 Predicament of women in India: Witch Branding Author- Sneha Kumari, 10th Semester, BB.A.LL.B (H), Law College, Uttaranchal University, Dehradun. Co-Author- Dr. Vivek Kumar, Law College, Uttaranchal University, Dehradun. Abstract Witch hunting and branding women as a witch is essentially a legacy of violence against women in our society. By punishing those women who are seen as vile and wild, oppressors perhaps want to send a not so subtle message to women: docility and domesticity get rewarded; anything else gets punished. As soon as the women steps out their prescribed roles, they become targets. When women are branded as witches they are made to walk naked through the village, they are gang-raped, at times cut their breasts off, break their teeth or heads and forced to swallow urine and human faeces or eat human flesh or drink the blood of a chicken. There are thousands of women who face such brutal violence in each and every rural parts of India and superstitions are probably made to be the main reason behind all the murders and brutality towards women when the truth is they are simply used as an scapegoats and “superstitions are used as an excuse” only to hide the true motive behind those murders and brutality. This can also be called as a caste based practice where the members of upper caste society try to condemn and deter the poor and indigenous people by branding them as witches. Keywords- Scapegoat, Dayan, Sorcerer, Witch- hunting, Witch Branding Introduction Witch branding are the threat to the society. -

On the Divination Images of Flowers and Plants in Song Ci

Academic Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences ISSN 2616-5783 Vol.3, Issue 10: 130-135, DOI: 10.25236/AJHSS.2020.031017 On the divination images of flowers and plants in Song Ci Yi Wang1,* 1 College of Liberal Arts, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225002, China *Corresponding Author ABSTRACT. Flower divination is a special digital divination method that uses flowers and plants as a medium, and it has become a common cultural image in Song Ci. Flower and grass divination uses the odd and even number of petals and other body parts as hexagrams or double leaves and combined stems as auspicious signs as its test methods. The reason why the image of flower and grass divination can flourish in Song Ci is closely related to the highly developed divination culture and flower trade in the Song Dynasty. It also contains the national consciousness and national experience of number worship and number divination. KEYWORDS: flower divination, digital divination, cultural image, national consciousness 1. Introduction The Song Dynasty was a period of relatively prosperous culture, and divination was an important part of Song Dynasty culture. From the emperor to the ordinary citizens, divination penetrated into their cultural life and became a special sight in the urban life of the Song Dynasty. Take the literati as an example. Since the Jiayou period, "literati and bureaucrats have always used hexagram shadows". Flower and grass divination is a special way of divination. It uses flowers, grass, and leaves as the medium, and mostly uses odd and even numbers as hexagrams as its external manifestation. It is more common in Song Ci and became one of Song Ci. -

The Immigrant Artist at Work. Edwidge Danticat

New West Indian Guide Vol. 85, no. 3-4 (2011), pp. 265-339 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/index URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101708 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0028-9930 BOOK REVIEWS Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work. EDWIDGE DANTICAT. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. 189 pp. (Cloth US$ 19.95) COLIN DAYAN Department of English Vanderbilt University Nashville TN 37235, U.S.A. <[email protected]> In her response to a February 2011 exchange in Small Axe, Edwidge Danticat writes: “Absolute certainty is perhaps at the center of activism, but ambiva- lence is at the heart of art, where gray areas abound and nuance thrives.” What strikes me most in all of her writing is the grace attendant upon terror, her ability to reorient our understanding of the political. As I write, hundreds of people are being evicted from camps in Delmas, a neighborhood northeast of downtown Port-au-Prince. With machetes, knives, and batons, the police slashed, tore, and destroyed tents, the makeshift refuge of those displaced by the earthquake. Now, at the start of the hurricane season, amid heavy rains, those already dispossessed are penalized and thrust again into harm’s way. How, then, to write about Haiti – and refrain from anger? Create Danger ously dares readers to know the unspeakable. But what makes it remarkable is that the dare only works because Danticat is ever tasking herself to know, confront, and ultimately – and unbelievably – create, in spite of examples of greed, fanaticism, and cruelty. -

Empirical Inquiry Twenty-Five Years After the Lawyering Process Stefan H

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2003 Empirical Inquiry Twenty-Five Years After The Lawyering Process Stefan H. Krieger Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Richard K. Neumann Jr. Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Stefan H. Krieger and Richard K. Neumann Jr., Empirical Inquiry Twenty-Five Years After The Lawyering Process, 10 Clinical L. Rev. 349 (2003) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/155 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMPIRICAL INQUIRY TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AFTER THE LAWYERING PROCESS RICHARD K. NEUMANN, JR. & STEFAN H. KRIEGER* One of the many ways in which The Lawyering Process was a pioneering book was its extensive reliance on empirical research about lawyers, lawyering, and activities analogous to some or another aspect of lawyering. To what extent has the clinical field accepted Gary Bellow and Bea Moulton's invitation to explore empirical stud- ies generated outside legal education and perhaps engage in empirical work ourselves to understand lawyering more deeply? Although some clinicians have done good empirical work, our field as a whole has not really accepted Gary and Bea's invitation. This article ex- plains empirical ways of thinking and working; discusses some of the mistakes law scholars (not only clinicians) make when dealing with empirical work; explores some of the reasons why empiricism has encountered difficulty in law schools; and suggests that empiricism might in some ways improve our teaching in clinics. -

Superstition Found in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Developed By

Lesson Plan – Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Concept: Superstition found in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Developed by: Lori Rollison, Marceline High School, Marceline, Missouri Suggested Grade Level: 9-12 (can be adapted for use in middle school) Time Frame: 10 fifty-minute class periods (lessons can be combined to fit block schedule) Objectives: 1. Students will identify and explain five examples of superstitions found in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. 2. Students will create five new superstitions based on an area of interest. 3. Students will write a story that appropriately includes a superstition created by the student. State Standards: Missouri Show-Me Standards: CA1, CA2, CA4, CA6, CA7, SS6 Assessment/Evaluation: Students will create a list of five new superstitions that they create based on their own life and family values. With this list of superstitions, students will write a short story in which they incorporate their newfound superstitions. This story needs to follow standard writing format, and needs to be told from the viewpoint of Huck Finn. The text should be written in a dialect similar to what appears in the original Mark Twain text. In addition, students will include illustrations that depict the superstitions as they occur within the story. Language/Vocabulary: Found Poem: a poem consisting of words found in a non-poetic context and usually broken into lines that convey a verse rhythm (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/found%20poem). Superstition: 1 a: a belief or practice resulting from ignorance, fear of the unknown, trust in magic or chance, or a false conception of causation b: an irrational abject attitude of mind toward the supernatural, nature, or God resulting from superstition 2: a notion maintained despite evidence to the contrary http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/superstition Integrated Curriculum: Integration into a history class is possible with this lesson in terms of discussing the history of superstitions in general, or more specifically as they appear in Mark Twain’s text. -

Expansion of Consciousness: English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 063 292 TE 002 911 AUTHOR Kenzel, Elaine; Williams, Jean TITLE Expansion of Consciousness:.English. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 58p.; Authorized Course of InstructiGn for the Quinmester Program EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 BC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; *Compositior (Literary); Comprehension Development; *Emotic il Experience; Group Experience; Individual Development; *Perception; Psychological Patterns; *Sensory Experience; Stimuli; *Stimulus Behavior; Thought Processes IDENTIFIERS *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT A course that capitalizes on individual and group experiences and encourages students to expand their powers of observation and discernment is presented in the course, students analyzing their thoughts and translate them into written responses. The performance objectives are: A. Given opportunities to experience sensory and emotional stimuli, students will demonstrate an expanding awareness of each sense; B. Given opportunities to experience intellectual challenges, students will demonstrate an increasing comprehension with each situation; and C. Given opportunities to delve into moot phenomena, students will discern for themselves what is real and what is not real. Emphasis is placed on Teaching Strategies, which are approximately 178 suggestions tor the teacher's use in accomplishing the course objectives. Included are the course content and student and teacher resources.(Author/LS) ,, U.S. DEPARTMUIT OF HEALTH.EDUCATION St WELFARE I: OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEENREPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THEPERSON DR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT,POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOTNECES. SARILT REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICEOF EDU. CATION POSITION OR POLICY. AUTHORIZED COURSE OF INSTRUCTION FOR THE 3:0 EXPANSION OF CONSCIOUSNESS rims cm, 53.3.1.3.0 513.2 5113.10 533.4ao 5315ao 'PERMISSION TO-REPRODUCE THIS , -13 5116ao tiOPYRIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED = BY DADL-TcLICAtTY RIEV-1 r cm: TO ERIC AND OMANI/KOONS OPERATING ce) UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE U.S. -

Fiddler on the Roof 6/96

Civil War Study Guide.qxd 9/13/01 10:31 AM Page 3 MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL is one of the world’s major dramatic licensing agencies, specializing in Broadway, Off-Broadway and West End musicals. Since its founding in 1952, MTI has been responsible for supplying scripts and musical materials to theatres worldwide and for protecting the rights and legacy of the authors whom it represents. It has been a driving force in cultivating new work and in extending the production life of some of the classics: Guys and Dolls, West Side Story, Fiddler On The Roof, Les Misérables, Annie, Of Thee I Sing, Ain’t Misbehavin’, Damn Yankees, The Music Man, Evita, and the complete musical theatre works of composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim, among others. Apart from the major Broadway and Off- Broadway shows, MTI is proud to represent youth shows, revues and musicals which began life in regional theatres and have since become worthy additions to the musical theatre canon. MTI shows have been performed by 30,000 amateur and professional theatrical organizations throughout the U.S. and Canada, and in over 60 countries around the world. Whether it’s at a high school in Kansas, by an all-female troupe in Japan or the first production of West Side Story ever staged in Estonia, productions of MTI musicals involve over 10 million people each year. Although we value all our clients, the twelve thousand high schools who perform our shows are of particular importance, for it is at these schools that music and drama educators work to keep theatre alive in their community. -

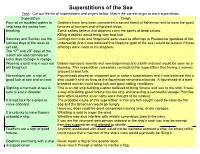

Superstitions of the Sea Task: Cut out the List of Superstitions and Origins Below

Superstitions of the Sea Task: Cut out the list of superstitions and origins below. Match the correct origin to each superstition. Superstition Origin Pour oil on troubled waters to Dolphins have long been considered a sacred friend of fishermen and to have the good help keep the waves from fortunes of humans and will protect ships. breaking Some sailors believe that dolphins carry the spirits of dead sailors. Killing a dolphin would bring very bad luck. Saturday and Sunday are the Cuttings form hair and fingernails were used as offerings to Prosperina (goddess of the luckiest days of the week to underworld) And it was believed that Neptune (god of the sea) would be jealous if these set sail. offerings were made in his kingdom. The 17th and 29th days of the month are also considered lucky days to begin a voyage. Wearing a gold ring in your ear Babies represent new life and new beginnings and a birth onboard would be seen as a will bring luck blessing. This superstition completely contradicts the superstition that having a woman onboard is bad luck. Horseshoes are a sign of Figureheads played an important part in sailor’s superstitions and it was believed that a good luck at sea and on land ship couldn’t sink as long as the figurehead remained attached. A figurehead of a bare breasted woman could bring luck and good dialing conditions. Sighting a mermaid at sea is This is an old ship building custom believed to bring fortune and luck to the ship. It was sure to end in disaster a way of building good fortune into the ship and ensuring a successful voyage.