Working Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jefferson County Parks, Recreation & Open Space Plan Update 2015

Jefferson County Parks, Recreation & Open Space Plan Update 2015 Jefferson County Parks and Recreation Department of Public Works 623 Sheridan Street Port Townsend, Washington 98368 360-385-9160 Jefferson County Parks, Recreation & Open Space Plan 2015 Lake Leland Community Park Acknowledgements PUBLIC WORKS Monte Reinders, P.E. Public Works Director/County Engineer PARKS AND RECREATION STAFF Matt Tyler, Manager, MPA, CPRE Molly Hilt, Parks Maintenance Chris Macklin, Assistant Recreation Manager Irene Miller, Parks Maintenance Jessica Winsheimer, Recreation Aide Supervisor PARKS AND RECREATION ADVISORY BOARD District #1 Jane Storm Rich Stapf, Jr. Tim Thomas District #2 Roger Hall Gregory Graves Evan Dobrowski District #3 Michael McFadden Clayton White Douglas Huber JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS District #1 Phil Johnson District #2 David Sullivan District #3 John Austin and Kathleen Kler1 Prepared by: Arvilla Ohlde, CPRP AjO Consulting 1 (transition occurred during adoption phase) Table of Contents Preface Executive Summary Chapters Page Chapter 1 Introduction & County Profile…………………………..………….…1 Chapter 2 Goals & Objectives……………………………………………………....7 Chapter 3 Public Involvement…………………………………………………….15 Chapter 4 Existing Facility & Program Inventory……………………… ………23 Chapter 5 Demand & Needs Analysis……………………………………………58 Chapter 6 Recommendations /Action Plan………………………………………………….……..…105 Chapter 7 Funding / Capital Improvement Plan……………………………………………..………123 Appendix A Park & Facility Descriptions Appendix B 1. Public Involvement/Community Questionnaire 2. Jefferson County Park & Recreation Advisory Board Motion to Adopt 2015 PROS Plan 3. RCO Level of Service Summary/Local Agencies 4. Recreation & Conservation Office Self-Certification 5. Jefferson County Adopting Resolution 6. Exploratory Regional Parks and Recreation Committee’s Recommendations June 19, 2012 Preface On behalf of all the Jefferson County Parks and Recreation Advisory Board Members that helped with its creation, I am pleased to present the 2015-2021 Parks, Recreation and Open Space Plan. -

Juniors Pick Prom Queen; Call Lanin, Devron to Play

Vol. XLI, No. 15 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D, C. Thursday, February 18, 1960 Parents &. Profs History Fraternity Set Get-Together Names 4 Seniors Juniors Pick Prom Queen; For Next Sunday For Membership Next Sunday, February 21, Call Lanin, Devron To Play will witness the Washington The Georgetown Beta-Phi Club's Fifth Annual Recep chapter of Phi Alpha Theta, Coughlin Promises tion for the Faculty of the national honor history fra Hawaiian Weekend College and the parents of the ternity, founded in 1921, has non-resident students. recently elected four new The Junior Prom, a yearly A full afternoon has been members from the College. tradition here at the Hilltop, planned, beginning in Gaston Hall They are seniors John Cole will enliven the weekend of at 2 p.m. with a short concert by the Chimes and a greeting to the man, Bob Di Maio, Arnold February 26. The events are parents by Rev. Joseph A. Sellin Donahue, and Al Staebler. open to all students in the ger, Dean of the College. Under the auspices of Dr. Tibor . University, not just the junior Kerekes, the Georgetown chapter class. Chairman of the fete is im has grown, since its inception in presario Paul J. Coughlin. Cough 1948, to three hundred members lin is an AB (Classical) economics and is one of the most active in the fraternity. major and a member of the Class The first admitted among Catho of '61. He was on the Spring Week lic universities, it comprises mem end Committee last year and is bers from the College, Foreign present.ly a membe1.· of the N. -

Jefferson County Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment 2011 2

Jefferson County Department of Emergency Management 81 Elkins Road, Port Hadlock, Washington 98339 - Phone: (360) 385-9368 Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 I. INTRODUCTION 6 II. GEOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS 6 III. DEMOGRAPHIC ASPECTS 7 IV. SIGNIFICANT HISTORICAL DISASTER EVENTS 9 V. NATURAL HAZARDS 12 • AVALANCHE 13 • DROUGHT 14 • EARTHQUAKES 17 • FLOOD 24 • LANDSLIDE 32 • SEVERE LOCAL STORM 34 • TSUNAMI / SEICHE 38 • VOLCANO 42 • WILDLAND / FOREST / INTERFACE FIRES 45 VI. TECHNOLOGICAL (HUMAN MADE) HAZARDS 48 • CIVIL DISTURBANCE 49 • DAM FAILURE 51 • ENERGY EMERGENCY 53 • FOOD AND WATER CONTAMINATION 56 • HAZARDOUS MATERIALS 58 • MARINE OIL SPILL – MAJOR POLLUTION EVENT 60 • SHELTER / REFUGE SITE 62 • TERRORISM 64 • URBAN FIRE 67 RESOURCES / REFERENCES 69 Jefferson County Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment 2011 2 PURPOSE This Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment (HIVA) document describes known natural and technological (human-made) hazards that could potentially impact the lives, economy, environment, and property of residents of Jefferson County. It provides a foundation for further planning to ensure that County leadership, agencies, and citizens are aware and prepared to meet the effects of disasters and emergencies. Incident management cannot be event driven. Through increased awareness and preventive measures, the ultimate goal is to help ensure a unified approach that will lesson vulnerability to hazards over time. The HIVA is not a detailed study, but a general overview of known hazards that can affect Jefferson County. Jefferson County Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment 2011 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An integrated emergency management approach involves hazard identification, risk assessment, and vulnerability analysis. This document, the Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment (HIVA) describes the hazard identification and assessment of both natural hazards and technological, or human caused hazards, which exist for the people of Jefferson County. -

Life in Utah. TABLE of CONTENTS

Life In Utah - Table of Contents. Life In Utah. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Title Page, Preface, And List of Illustrations. The Map from the book. Just use your back button to return. CHAPTER I. HISTORICAL. Birth and early life of the Mormon Prophet-The original Smith family - Opinion of Brigham Young-The "peep-stone" - "Calling" of Joe Smith - The Golden Plates - "Reformed Egyptian" translated - "Book of Mormon" published - Synopsis of its contents - Real author of the work - "The glorious six" first converts - Emma Smith, "Elect Lady and Daughter of God" - Sidney Rigdon takes the field - First Hegira - "Zion" in Missouri - Kirtland Bank - Swindling and "persecution " - War in Jackson County - Smith "marches on Missouri" - Failure of the "Lord's Bank" - Flight of the Prophet - "Mormon War" - Capture of Smith Flight into Illinois............................................................... 21 CHAPTER II. HISTORY FROM THE FOUNDING OF NAUVOO TILL 1843. Rapid growth of Nauvoo - Apparent prosperity - "The vultures gather to the carcass" - Crime, polygamy and politics - Subserviency of the Politicians - Nauvoo Charters - A government within a government - Joe Smith twice arrested - Released by S. A. Douglas - Second time by Municipal Court of Nauvoo - McKinney's account Petty thieving - Gentiles driven out of Nauvoo - "Whittling-Deacons" - "Danites" - Anti-Mormons organize a Political Party - Treachery of Davis and Owens - Defeat of Anti-Mormons - Campaign of 1843 - Cyrus Walker, a great Criminal Lawyer - "Revelation" on voting - The Prophet cheats the lawyer - Astounding perfidy of the Mormon leaders - Great increase of popular hatred - Just anger against the Saints..................................................... 58 CHAPTER III. MORMON DIFFICULTIES AND DEATH OF THE PROPHET. Ford's account - Double treachery in the Quincy district - New and startling developments in file:///C|/WINDOWS/Desktop/Acrobat Version/beadleindexcd.html (1 of 8) [1/24/2002 8:48:25 PM] Life In Utah - Table of Contents. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

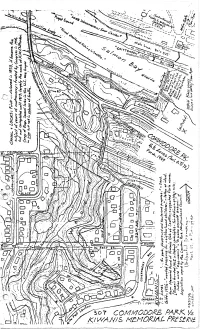

Commodore Park Assumes Its Name from the Street Upon Which It Fronts

\\\\. M !> \v ri^SS«HV '/A*.' ----^-:^-"v *//-£ ^^,_ «•*_' 1 ^ ^ : •'.--" - ^ O.-^c, Ai.'-' '"^^52-(' - £>•». ' f~***t v~ at, •/ ^^si:-ty .' /A,,M /• t» /l»*^ »• V^^S^ *" *9/KK\^^*j»^W^^J ** .^/ ii, « AfQVS'.#'ae v>3 ^ -XU ^4f^ V^, •^txO^ ^^ V ' l •£<£ €^_ w -* «»K^ . C ."t, H 2 Js * -^ToT COMMODOR& P V. KIWAN/S MEMORIAL ru-i «.,- HISTORY: PARK When "Indian Charlie" made his summer home on the site now occupied by the Locks there ran a quiet stream from "Tenus Chuck" (Lake Union) into "Cilcole" Bay (Salmon Bay and Shilshole Bay). Salmon Bay was a tidal flat but the fishing was good, as the Denny brothers and Wil- liam Bell discovered in 1852, so they named it Salmon Bay. In 1876 Die S. Shillestad bought land on the south side of Salmon Bay and later built his house there. George B. McClellan (famed as a Union General in the Civil War) was a Captain of Engineers in 1853 when he recommended that a canal be dug from Lake Washington to Puget Sound, a con- cept endorsed by Thomas Mercer in an Independence Day celebration address the following year which he described as a union of lakes and bays; and so named Lake Union and Union Bay. Then began a series of verbal battles that raged for some 60 years from here to Washington, D.C.! Six different channel routes were not only proposed but some work was begun on several. In §1860 Harvey L. Pike took pick and shovel and began digging a ditch between Union Bay and Lake i: Union, but he soon tired and quit. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

Oregon's Civil

STACEY L. SMITH Oregon’s Civil War The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest WHERE DOES OREGON fit into the history of the U.S. Civil War? This is the question I struggled to answer as project historian for the Oregon Historical Society’s new exhibit — 2 Years, Month: Lincoln’s Legacy. The exhibit, which opened on April 2, 2014, brings together rare documents and artifacts from the Mark Family Collection, the Shapell Manuscript Founda- tion, and the collections of the Oregon Historical Society (OHS). Starting with Lincoln’s enactment of the final Emancipation Proclamation on January , 863, and ending with the U.S. House of Representatives’ approval of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery on January 3, 86, the exhibit recreates twenty-five critical months in the lives of Abraham Lincoln and the American nation. From the moment we began crafting the exhibit in the fall of 203, OHS Museum Director Brian J. Carter and I decided to highlight two intertwined themes: Lincoln’s controversial decision to emancipate southern slaves, and the efforts of African Americans (free and enslaved) to achieve freedom, equality, and justice. As we constructed an exhibit focused on the national crisis over slavery and African Americans’ freedom struggle, we also strove to stay true to OHS’s mission to preserve and interpret Oregon’s his- tory. Our challenge was to make Lincoln’s presidency, the abolition of slavery, and African Americans’ quest for citizenship rights relevant to Oregon and, in turn, to explore Oregon’s role in these cataclysmic national processes. This was at first a perplexing task. -

Beyond the Paths of Heaven the Emergence of Space Power Thought

Beyond the Paths of Heaven The Emergence of Space Power Thought A Comprehensive Anthology of Space-Related Master’s Research Produced by the School of Advanced Airpower Studies Edited by Bruce M. DeBlois, Colonel, USAF Professor of Air and Space Technology Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beyond the paths of heaven : the emergence of space power thought : a comprehensive anthology of space-related master’s research / edited by Bruce M. DeBlois. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Astronautics, Military. 2. Astronautics, Military—United States. 3. Space Warfare. 4. Air University (U.S.). Air Command and Staff College. School of Advanced Airpower Studies- -Dissertations. I. Deblois, Bruce M., 1957- UG1520.B48 1999 99-35729 358’ .8—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-58566-067-1 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii OVERVIEW . ix PART I Space Organization, Doctrine, and Architecture 1 An Aerospace Strategy for an Aerospace Nation . 3 Stephen E. Wright 2 After the Gulf War: Balancing Space Power’s Development . 63 Frank Gallegos 3 Blueprints for the Future: Comparing National Security Space Architectures . 103 Christian C. Daehnick PART II Sanctuary/Survivability Perspectives 4 Safe Heavens: Military Strategy and Space Sanctuary . 185 David W. Ziegler PART III Space Control Perspectives 5 Counterspace Operations for Information Dominance . -

2011 Washington Fishing Prospects

2011 Washington Fishing Prospects WHERE TO CATCH FISH IN THE EVERGREEN STATE Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE 600 Capitol Way N – Olympia, WA 98501-1091 http://wdfw.wa.gov 1 CONTENTS Agency’s Contact Information 3 WDFW Regional Office Contact Information 4 What’s New for 2011-2012 Season? 5 Introduction 6 Licensing 10 License types and fees 11 Juvenile, Youth, Senior information 11 Military Licensing information 11 Fishing Kids Program and Schedule 12 “Go Play Outside” Initiative 13 Fish Consumption (Health) Advisories 13 Accessible Fishing for Persons with Disabilities 14 Accessible Outdoor Recreation Guild 15 Launch and Moorage Locations 15 Washington State Parks 15 Sport Fish of Washington 16 County-by-County Listings 30 Juvenile-Only and other special fishing waters in Washington 146 Fly-fishing Only waters in Washington 148 2011 Triploid Rainbow Trout Stocking Information 149 WDFW State Record Sport Fish Application information 149 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This publication is produced by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Inland Fish Program Manager, Jim Uehara, using information supplied by the Department’s field biological staff, including: Eric Anderson, Charmane Ashbrook, Steve Caromile, Jim Cummins, Wolf Dammers, Chris Donley, Mark Downen, Rick Ereth, Joe Hymer, Paul Hoffarth, Chad Jackson, Bob Jateff, Thom Johnson, Jeff Korth, Glen Mendel, Larry Phillips, Mike Scharpf, Art Viola, John Weinheimer, and no doubt other staff that were inadvertently omitted. Accessibility and Boating information is provided by the -

2020-21 Husky Basketball Record Book 2020-21 Tv/Radio Roster

2020-21 HUSKY BASKETBALL RECORD BOOK 2020-21 TV/RADIO ROSTER Marcus Tsohonis Nate Roberts Nate Pryor Jamal Bey Erik Stevenson Hameir Wright 0 6-3 • 190 • So. • G 1 6-11 • 265 • RSo. • F 4 6-4 • 175 • Jr. • G 5 6-6 • 210 • Jr. • G 10 6-3 • 200 • Jr. • G 13 6-9 • 220 • Sr. • F Portland, Ore. Washington, D.C. Seattle, Wash. Las Vegas, Nev. Lacey, Wash. Albany, N.Y. Kyle Luttinen Griff Hopkins RaeQuan Battle Cole Bajema Jonah Geron Travis Rice 14 6-7 • 185 • Fr. • G 15 6-4 • 185 • Fr. • F 21 6-5 • 175 • So. • G 22 6-7 • 190 • So. • G 24 6-5 • 195 • RSo. • G 30 6-2 • 185 • RSr. • G Seattle, Wash. Syracuse, N.Y. Tulalip, Wash. Lynden, Wash. Fresno, Calif. Las Vegas, Nev. Noah Neubauer J’Raan Brooks Reagan Lundeen Riley Sorn Quade Green 32 6-2 • 190 • RSo. • G 33 6-9 • 220 • RSo. • F 34 6-6 • 230 • Jr. • F 52 7-4 • 255 • RSo. • C 55 6-0 • 170 • Sr. • G Seattle, Wash. Seattle, Wash. Santa Ana, Calif. Richland, Wash. Philadelphia, Pa. Mike Hopkins Dave Rice Will Conroy Cameron Dollar Jerry Hobbie Head Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Special Assistant to the Head Coach (4th season) (4th season) (6th season) (4th season) (4th season) Michael Bowden Pat Jenkins Todd Tuetken Aaron Blue Kevin Dunleavy Director of Basketball Operations Athletic Trainer Strength & Conditioning Video and Analytics Coordinator Director of Special Projects (1st season) (19th season) (4th season) (3rd season) (1st season) Back Row (L-R): Quade Green, Erik Stevenson, Griff Hopkins, Jonah Geron, Marcus Tsohonis, Jamal Bey, Noah Neubauer, Nate Pryor, Travis Rice Front Row (L-R): Kyle Luttinen, Reagan Lundeen, J’Raan Brooks, Riley Sorn, Nate Roberts, Hameir Wright, Cole Bajema 2020-21 Washington Men’s Basketball Roster NUMERICAL ROSTER NO NAME POS HT WT CL EXP HOMETOWN (HIGH SCHOOL/LAST SCHOOL) 0 Marcus Tsohonis G 6-3 190 So. -

Heinrich Zimmermann and the Proposed Voyage of the Imperial and Royal Ship Cobenzell to the North West Coast in 1782-17831 Robert J

Heinrich Zimmermann and the Proposed Voyage of the Imperial and Royal Ship Cobenzell to the North West Coast in 1782-17831 Robert J. King Johann Heinrich Zimmermann (1741-1805) a navigué sur le Discovery lors du troisième voyage de James Cook au Pacifique (1776-1780) et a écrit un compte du voyage, Reise um die Welt mit Capitain Cook (Mannheim, 1781). En 1782 il a été invité par William Bolts à participer à un voyage à la côte nord-ouest de l'Amérique partant de Trieste sous les couleurs autrichiennes impériales. Ce voyage était conçu comme réponse autrichienne aux voyages de Cook, un voyage impérial de découverte autour du monde qui devait comprendre l'exploitation des possibilités commerciales du commerce des fourrures sur la côte nord- ouest et le commerce avec la Chine et le Japon. Zimmermann a été rejoint à Trieste par trois de ses anciens compagnons de bord sous Cook -- George Dixon, George Gilpin et William Walker, chacun destiné à naviguer comme officier sur le navire impérial et royal Cobenzell. Les lettres et le journal de Zimmermann qui ont survécu fournissent une source valable à cette étude des origines du commerce maritime des fourrures sur la côte nord-ouest. On 24 July 1782, George Dixon wrote from Vienna to Heinrich Zimmermann, his former shipmate on the Discovery during James Cook’s 1776-1780 expedition to the North Pacific: Dear Harry, Yours I Rec‘d, and am glad you have Resolution, like the Honest Sailor which I allways have taken you for, and are willing to be doing sum thing both for your self and the Country.