Oregon's Civil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SEN ATE. JUNE 15 ' 1\Ir

1921. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 2579 George Lawrence Thoma . Hunter J. Norton. Passed ass-istant paymaster tcith mnk of lieutenant. Sumuel Lawrence Bates. Walter E. Scott. Cyrus D. Bishop. John Charles Poshepny. John H. Skillman. MABI ~ CORPS. Gordon Samuel Bower. Maurice M. Smith. Captain. Edward 1\Iixon. John 1\I. Speissegger. Henry Chilton 1\IcGinnis. Leslie A. 'Villiams. Patrick W. Guilfoyle. F rank J oseph 1\Ianley. George F. Yo ran. Fi1·st lie'lttenant. Harry Franris Hake. Charles Frederick House. Jud on H. Fitzgerald. .Julius Joseph Miffitt. Louis Weigle Crane. Second lieutenants. Harry Gillespie Kinnard. Calvin William Schaeffer. James l\1. White. Percival Francis Patten. Benjamin Oliver Kilroy. Gerald C. Thomas. Michael Albert Sprengel. Letcher Pittman. 'Villiam Edwin l\lcCain. Frank Humbeutel. Golden Fletcher Davis. Robert Hill Whitaker. Grandison James Tyler. "\Villiam Starling Cooper. SENATE. Theodore Martin Stock. Charles Ernest Leavitt. Stamford Grey Chapman. Archie Bawlin 1\IcKay. WEDNESDAY, J1.ene 15, 19~1. ·william Elliott. Harrison \Villiam Mc- Joseph Edward Ford. Grath. (Legislati'Ve day ot Mo-nday, Jttne 13, 1921.) .Tames Edward Hunt. Charles Thomns Flannery. The Senate met nt 11 o'clock a. m., on the expiration of the Hugh John McManu ·. Josephus Maximilian Lie- recess. 'Villiam Edward Woods. ber. l\Ir. SMOOT. Mr. President, I suggest the absence of a Alexander Wolseley Urqu- Carl Louis Biery. quorum. hart. Harry Carl l\fechtoldt. The VICE PRESIDENT. The Secretary will call the rolL Leo .Adelbert Ketterer. Harry Herbert Hines. The reading clerk called the roll, and the following Senators John Jo. eph Carroll. Charles ·welford Fox. answered to theil· names : Edward. -

A Geophysical Study of the North Scappoose Creek, Alder Creek, Clatskanie River Lineament, Along the Trend of the Portland Hills Fault, Columbia County, Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1982 A geophysical study of the North Scappoose Creek, Alder Creek, Clatskanie River lineament, along the trend of the Portland Hills fault, Columbia County, Oregon Nina Haas Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Tectonics and Structure Commons Recommended Citation Haas, Nina, "A geophysical study of the North Scappoose Creek, Alder Creek, Clatskanie River lineament, along the trend of the Portland Hills fault, Columbia County, Oregon" (1982). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3254. 10.15760/etd.3244 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nina Haas for the Master of Science in Geology presented December 15, 1982. Title: A Geophysical Study of the North Scappoose Creek - Alder Creek - Clatskanie River Lineament, Along the Trend of the Portland Hills Fault, Columbia County, Oregon. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Chairman Giibett • Benson The Portland Hills fault forms a strong northwest trending lineament along the east side of the Tualatin Mountains. An en echelon lineament follows North Scappoose Creek, Alder Creek, and the Clatskanie River along the same trend, through Columbia County, Oregon. The possibility that this lineament follows a fault or fault zone was investigated in this study. Geophysical methods were used, with seismic 2 refraction, magnetic and gravity lines run perpendicular to the lineament. -

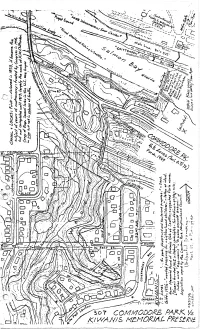

Commodore Park Assumes Its Name from the Street Upon Which It Fronts

\\\\. M !> \v ri^SS«HV '/A*.' ----^-:^-"v *//-£ ^^,_ «•*_' 1 ^ ^ : •'.--" - ^ O.-^c, Ai.'-' '"^^52-(' - £>•». ' f~***t v~ at, •/ ^^si:-ty .' /A,,M /• t» /l»*^ »• V^^S^ *" *9/KK\^^*j»^W^^J ** .^/ ii, « AfQVS'.#'ae v>3 ^ -XU ^4f^ V^, •^txO^ ^^ V ' l •£<£ €^_ w -* «»K^ . C ."t, H 2 Js * -^ToT COMMODOR& P V. KIWAN/S MEMORIAL ru-i «.,- HISTORY: PARK When "Indian Charlie" made his summer home on the site now occupied by the Locks there ran a quiet stream from "Tenus Chuck" (Lake Union) into "Cilcole" Bay (Salmon Bay and Shilshole Bay). Salmon Bay was a tidal flat but the fishing was good, as the Denny brothers and Wil- liam Bell discovered in 1852, so they named it Salmon Bay. In 1876 Die S. Shillestad bought land on the south side of Salmon Bay and later built his house there. George B. McClellan (famed as a Union General in the Civil War) was a Captain of Engineers in 1853 when he recommended that a canal be dug from Lake Washington to Puget Sound, a con- cept endorsed by Thomas Mercer in an Independence Day celebration address the following year which he described as a union of lakes and bays; and so named Lake Union and Union Bay. Then began a series of verbal battles that raged for some 60 years from here to Washington, D.C.! Six different channel routes were not only proposed but some work was begun on several. In §1860 Harvey L. Pike took pick and shovel and began digging a ditch between Union Bay and Lake i: Union, but he soon tired and quit. -

Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 Cessna R. Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Cessna R., "The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 258. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 by Cessna R. Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: William L. Lang, Chair David A. Horowitz David A. Johnson Barbara A. Brower Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how the pursuit of commercial gain affected the development of agriculture in western Oregon’s Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River Valleys. The period of study begins when the British owned Hudson’s Bay Company began to farm land in and around Fort Vancouver in 1825, and ends in 1861—during the time when agrarian settlement was beginning to expand east of the Cascade Mountains. Given that agriculture -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

Oregon Coast Bibliography by Unknown Bancroft, Hubert Howe

Oregon Coast Bibliography By Unknown Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of the Northwest Coast. Vol. 1: 1543-1800. San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft, 1884. Beck, David R.M. Seeking Recognition: The Termination and Restoration of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians, 1855-1984. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009. _____. “’Standing out Here in the Surf’: The Termination and Restoration of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians of Western Oregon in Historical Perspective.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 110:1 (Spring 2009): 6-37. Beckham, Stephen Dow. “History of Western Oregon Since 1846.” In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 7: Northwest Coast, ed. Wayne Suttles and William Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990. _____. The Indians of Western Oregon: This Land Was Theirs. Coos Bay, OR: Arago Books, 1977. _____. Requiem for a People: The Rogue Indians and the Frontiersmen. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1996. First published 1971. _____. Oregon Indians: Voices from Two Centuries. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2006. Berg, Laura, ed. The First Oregonians. Portland: Oregon Council for the Humanities, 2007. Bingham, Edwin R., and Glen A. Love, eds. Northwest Perspectives: Essays on the Culture of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979. Boag, Peter. Environment and Experience: Settlement Culture in Nineteenth-Century Oregon. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. Bourhill, Bob. History of Oregon’s Timber Harvests and/or Lumber Production. Salem: Oregon Department of Forestry, 1994. Bowen, William Adrian. “Migration and Settlement on a Far Western Frontier: Oregon to 1850.” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1972. Boyd, Robert T., Kenneth M. -

Grain, Flour and Ships – the Wheat Trade in Portland, Oregon

Grain, Flour and Ships The Wheat Trade in Portland, Oregon Postcard Views of the Oregon Grain Industry, c1900 Prepared for Prosper Portland In Partial Fulfillment of the Centennial Mills Removal Project Under Agreement with the Oregon SHPO and the USACE George Kramer, M.S., HP Sr. Historic Preservation Specialist Heritage Research Associates, Inc. Eugene, Oregon April 2019 GRAIN, FLOUR AND SHIPS: THE WHEAT TRADE IN PORTLAND, OREGON By George Kramer Prepared for Prosper Portland 222 NW Fifth Avenue Portland, OR 97209 Heritage Research Associates, Inc. 1997 Garden Avenue Eugene, Oregon 97403 April 2019 HERITAGE RESEARCH ASSOCIATES REPORT NO. 448 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ........................................................................................................................... v 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 2. Historic Overview – Grain and Flour in Portland .............................................................. 4 Growing and Harvesting 4 Transporting Grain to Portland ................................................................................... 6 Exporting from Portland ............................................................................................. 8 Flour Mills ................................................................................................................. -

Opening Brief of Intervenors-Appellants Elizabeth Trojan, David Delk, and Ron Buel

FILED July 12, 2019 04:42 AM Appellate Court Records IN THE SUPREME COURT THE STATE OF OREGON In the Matter of Validation Proceeding To Determine the Regularity and Legality of Multnomah County Home Rule Charter Section 11.60 and Implementing Ordinance No. 1243 Regulating Campaign Finance and Disclosure. MULTNOMAH COUNTY, Petitioner-Appellant, and ELIZABETH TROJAN, MOSES ROSS, JUAN CARLOS ORDONEZ, DAVID DELK, JAMES OFSINK, RON BUEL, SETH ALAN WOOLLEY, and JIM ROBISON, Intervenors-Appellants, and JASON KAFOURY, Intervenor, v. ALAN MEHRWEIN, PORTLAND BUSINESS ALLIANCE, PORTLAND METROPOLITAN ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS, and ASSOCIATED OREGON INDUSTRIES, Intervenors-Respondents Multnomah County Circuit Court No. 17CV18006 Court of Appeals No. A168205 Supreme Court No. S066445 OPENING BRIEF OF INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS ELIZABETH TROJAN, DAVID DELK, AND RON BUEL On Certi¡ ed Appeal from a Judgment of the Multnomah County Circuit Court, the Honorable Eric J. Bloch, Judge. caption continued on next page July 2019 LINDA K. WILLIAMS JENNY MADKOUR OSB No. 78425 OSB No. 982980 10266 S.W. Lancaster Road KATHERINE THOMAS Portland, OR 97219 OSB No. 124766 503-293-0399 voice Multnomah County Attorney s Office 855-280-0488 fax 501 SE Hawthorne Blvd., Suite 500 [email protected] Portland, OR 97214 503-988-3138 voice Attorney for Intervenors-Appellants [email protected] Elizabeth Trojan, David Delk, and [email protected] Ron Buel Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellant Multnomah County DANIEL W. MEEK OSB No. 79124 10949 S.W. 4th Avenue GREGORY A. CHAIMOV Portland, OR 97219 OSB No. 822180 503-293-9021 voice Davis Wright Tremaine LLP 855-280-0488 fax 1300 SW Fifth Avenue, Suite 2400 [email protected] Portland, OR 97201 503-778-5328 voice Attorney for Intervenors-Appellants [email protected] Moses Ross, Juan Carlos Ordonez, James Ofsink, Seth Alan Woolley, Attorney for Intervenors-Resondents and Jim Robison i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

Autographs – Auction November 8, 2018 at 1:30Pm 1

Autographs – Auction November 8, 2018 at 1:30pm 1 (AMERICAN REVOLUTION.) CHARLES LEE. Brief Letter Signed, as Secretary 1 to the Board of Treasury, to Commissioner of the Continental Loan Office for the State of Massachusetts Bay Nathaniel Appleton, sending "the Resolution of the Congress for the Renewal of lost or destroyed Certificates, and a form of the Bond required to be taken on every such Occasion" [not present]. ½ page, tall 4to; moderate toning at edges and horizontal folds. Philadelphia, 16 June 1780 [300/400] Charles Lee (1758-1815) held the post of Secretary to the Board of Treasury during 1780 before beginning law practice in Virginia; he served as U.S. Attorney General, 1795-1801. From the Collection of William Wheeler III. (AMERICAN REVOLUTION.) WILLIAM WILLIAMS. 2 Autograph Document Signed, "Wm Williams Treas'r," ordering Mr. David Lathrop to pay £5.16.6 to John Clark. 4x7½ inches; ink cancellation through signature, minor scattered staining, folds, docketing on verso. Lebanon, 20 May 1782 [200/300] William Williams (1731-1811) was a signer from CT who twice paid for expeditions of the Continental Army out of his own pocket; he was a selectman, and, between 1752 and 1796, both town clerk and town treasurer of Lebanon. (AMERICAN REVOLUTION--AMERICAN SOLDIERS.) Group of 8 items 3 Signed, or Signed and Inscribed. Format and condition vary. Vp, 1774-1805 [800/1,200] Henry Knox. Document Signed, "HKnox," selling his sloop Quick Lime to Edward Thillman. 2 pages, tall 4to, with integral blank. Np, 24 May 1805 * John Chester (2). ALsS, as Supervisor of the Revenue, to Collector White, sending [revenue] stamps and home distillery certificates [not present]. -

Report on the History of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn

Report on the History of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn By David Alan Johnson Professor, Portland State University former Managing Editor (1997-2014), Pacific Historical Review Quintard Taylor Emeritus Professor and Scott and Dorothy Bullitt Professor of American History. University of Washington Marsha Weisiger Julie and Rocky Dixon Chair of U.S. Western History, University of Oregon In the 2015-16 academic year, students and faculty called for renaming Deady Hall and Dunn Hall, due to the association of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn with the infamous history of race relations in Oregon in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. President Michael Schill initially appointed a committee of administrators, faculty, and students to develop criteria for evaluating whether either of the names should be stripped from campus buildings. Once the criteria were established, President Schill assembled a panel of three historians to research the history of Deady and Dunn to guide his decision-making. The committee consists of David Alan Johnson, the foremost authority on the history of the Oregon Constitutional Convention and author of Founding the Far West: California, Oregon, Nevada, 1840-1890 (1992); Quintard Taylor, the leading historian of African Americans in the U.S. West and author of several books, including In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990 (1998); and Marsha Weisiger, author of several books, including Dreaming of Sheep in Navajo Country (2009). Other historians have written about Matthew Deady and Frederick Dunn; although we were familiar with them, we began our work looking at the primary sources—that is, the historical record produced by Deady, Dunn, and their contemporaries. -

Preliminary Draft

PRELIMINARY DRAFT Pacific Northwest Quarterly Index Volumes 1–98 NR Compiled by Janette Rawlings A few notes on the use of this index The index was alphabetized using the wordbyword system. In this system, alphabetizing continues until the end of the first word. Subsequent words are considered only when other entries begin with the same word. The locators consist of the volume number, issue number, and page numbers. So, in the entry “Gamblepudding and Sons, 36(3):261–62,” 36 refers to the volume number, 3 to the issue number, and 26162 to the page numbers. ii “‘Names Joined Together as Our Hearts Are’: The N Friendship of Samuel Hill and Reginald H. NAACP. See National Association for the Thomson,” by William H. Wilson, 94(4):183 Advancement of Colored People 96 Naches and Columbia River Irrigation Canal, "The Naming of Seward in Alaska," 1(3):159–161 10(1):23–24 "The Naming of Elliott Bay: Shall We Honor the Naches Pass, Wash., 14(1):78–79 Chaplain or the Midshipman?," by Howard cattle trade, 38(3):194–195, 202, 207, 213 A. Hanson, 45(1):28–32 The Naches Pass Highway, To Be Built Over the "Naming Stampede Pass," by W. P. Bonney, Ancient Klickitat Trail the Naches Pass 12(4):272–278 Military Road of 1852, review, 36(4):363 Nammack, Georgiana C., Fraud, Politics, and the Nackman, Mark E., A Nation within a Nation: Dispossession of the Indians: The Iroquois The Rise of Texas Nationalism, review, Land Frontier in the Colonial Period, 69(2):88; rev.