Global Librarianship (Books in Library and Information Science)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This PDF File

Editor: Henry Reichman, California State University, East Bay Founding Editor: Judith F. Krug (1940–2009) Publisher: Barbara Jones Office for Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association ISSN 1945-4546 March 2013 Vol. LXII No. 2 www.ala.org/nif Filtering continues to be an important issue for most schools around the country. That was the message of the American Association of School Librarians (AASL), a division of the American Library Association, national longitudinal survey, School Libraries Count!, conducted between January 24 and March 4, 2012. The annual sur- vey collected data on filtering based on responses to fourteen questions ranging from whether or not their schools use filters, to the specific types of social media blocked at their schools. AASL survey The survey data suggests that many schools are going beyond the requirements set forth by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in its Child Internet Protection explores Act (CIPA). When asked whether their schools or districts filter online content, 98% of the respon- dents said content is filtered. Specific types of filtering were also listed in the survey, filtering encouraging respondents to check any filtering that applied at their schools. There were in schools 4,299 responses with the following results: • 94% (4,041) Use filtering software • 87% (3,740) Have an acceptable use policy (AUP) • 73% (3,138) Supervise the students while accessing the Internet • 27% (1,174) Limit access to the Internet • 8% (343) Allow student access to the Internet on a case-by-case basis The data indicates that the majority of respondents do use filtering software, but also work through an AUP with students, or supervise student use of online content individually. -

IFLA National Libraries Section Newsletter, June 2010

IFLA National Libraries Section Newsletter, June 2010 Contents Editorial 2 IFLA WLIC Gothenburg 2010: Standing Committee Meeting 2 IFLA WLIC Gothenburg 2010: Joint session with Copyright and Other legal Matters 3 CDNL meeting 3 News from some Section members 4 Aruba .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Estonia .................................................................................................................................................. 6 France .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Germany .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Indonesia ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Mauritius ................................................................................................................................................ 10 New Zealand.......................................................................................................................................... 11 Russia ................................................................................................................................................ 12 Scotland ............................................................................................................................................... -

Worldcat Data Licensing

WorldCat Data Licensing 1. Why is OCLC recommending an open data license for its members? Many libraries are now examining ways that they can make their bibliographic records available for free on the Internet so that they can be reused and more fully integrated into the broader Web environment. Libraries may want to release catalog data as linked data, as MARC21 or as MARCXML. For an OCLC® member institution, these records may often contain data derived from WorldCat®. Coupled with a reference to the community norms articulated in WorldCat Rights and Responsibilities for the OCLC Cooperative, the Open Data Commons Attribution (ODC-BY) license provides a good way to share records that is consistent with the cooperative nature of OCLC cataloging. Best practices in the Web environment include making data available along with a license that clearly sets out the terms under which the data is being made available. Without such a license, users can never be sure of their rights to use the data, which can impede innovation. The VIAF project and the addition of Schema.org linked data to WorldCat.org records were both made available under the ODC-BY license. After much research and discussion, it was clear that ODC-BY was the best choice of license for many OCLC data services. The recommendation for members to also adopt this clear and consistent approach to the open licensing of shared data, derived from WorldCat, flowed from this experience. An OCLC staff group, aided by an external open-data licensing expert, conducted a structured investigation of available licensing alternatives to provide OCLC member institutions with guidance. -

Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt's Nineties Generation By

Writing in Cairo: Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt’s Nineties Generation by Nancy Spleth Linthicum A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein, Chair Associate Professor Samer Ali Professor Anton Shammas Associate Professor Megan Sweeney Nancy Spleth Linthicum [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9782-0133 © Nancy Spleth Linthicum 2019 Dedication Writing in Cairo is dedicated to my parents, Dorothy and Tom Linthicum, with much love and gratitude for their unwavering encouragement and support. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their invaluable advice and insights and for sticking with me throughout the circuitous journey that resulted in this dissertation. It would not have been possible without my chair, Carol Bardenstein, who helped shape the project from its inception. I am particularly grateful for her guidance and encouragement to pursue ideas that others may have found too far afield for a “literature” dissertation, while making sure I did not lose sight of the texts themselves. Anton Shammas, throughout my graduate career, pushed me to new ways of thinking that I could not have reached on my own. Coming from outside the field of Arabic literature, Megan Sweeney provided incisive feedback that ensured I spoke to a broader audience and helped me better frame and articulate my arguments. Samer Ali’s ongoing support and feedback, even before coming to the University of Michigan (UM), likewise was instrumental in bringing this dissertation to fruition. -

Swiss National Library. 102Nd Annual Report 2015

Swiss National Library 102nd Annual Report 2015 Interactive artists‘ books: three-dimensional projections that visitors can manipulate using gestures, e.g. Dario Robbiani’s Design your cake and eat it too (1996). Architectural guided tour of the NL. The Gugelmann Galaxy: Mathias Bernhard drew on the Gugelmann Collection to create a heavenly galaxy that visitors can move around using a smartphone. Table of Contents Key Figures 2 Libraries are helping to shape the digital future 3 Main Events – a Selection 6 Notable Acquisitions 9 Monographs 9 Prints and Drawings Department 10 Swiss Literary Archives 11 Collection 13 “Viva” project 13 Acquisitions 13 Catalogues 13 Preservation and conservation 14 Digital Collection 14 User Services 15 Circulation 15 Information Retrieval 15 Outreach 15 Prints and Drawings Department 17 Artists’ books 17 Collection 17 User Services 17 Swiss Literary Archives 18 Collection 18 User Services 18 Centre Dürrenmatt Neuchâtel 19 Finances 20 Budget and Expenditures 2014/2015 20 Funding Requirement by Product 2013-2015 20 Commission and Management Board 21 Swiss National Library Commission 21 Management Board 21 Organization chart Swiss National Library 22 Thanks 24 Further tables with additional figures and information regarding this annual report can be found at http://www.nb.admin.ch/annual_report. 1 Key Figures 2014 2015 +/-% Swiss literary output Books published in Switzerland 12 711 12 208 -4.0% Non-commercial publications 6 034 5 550 -8.0% Collection Collections holdings: publications (in million units) 4.44 -

OCLC and the Ethics of Librarianship: Using a Critical Lens to Recast a Key Resource

OCLC and the Ethics of Librarianship: Using a Critical Lens to Recast a Key Resource Maurine McCourry* Introduction Since its founding in 1967, OCLC has been a catalyst for dramatic change in the way that libraries organize and share resources. The organization’s structure has been self-described as a cooperative throughout its his- tory, but its governance has never strictly fit that model. There have always been librarians involved, and it has remained a non-profit organization, but its business model is strongly influenced by the corporate world, and many in the upper echelon of its leadership have come from that realm. As a result, many librarians have questioned OCLC’s role as a partner with libraries in providing access to information. There has been an undercurrent of belief that the organization does not really share the values of the profession, and does not necessarily ascribe to its ethics. This paper will explore the role the ethics of the profession of librarianship have, or should have, in both the governance of OCLC as an organization, and the use of its services by the library community. Using the frame- work of critical librarianship, it will attempt to answer the following questions: 1) What obligation does OCLC have to observe the ethics of librarianship?; 2) Do OCLC’s current practices fit within the guidelines established by the accepted ethics of the profession?; and 3) What are the responsibilities of the library community in ob- serving the ethics of the profession in relation to the services provided by OCLC? OCLC was founded with a mission of service to academic libraries, seeking to save library staff time and money while facilitating cooperative borrowing. -

Librarianship OCLC Research Serve and Advocate…Librarianship OCLC Research- VIAF

The Value Proposition – OCLC Global The Public Purpose Council Endeavors of OCLC April 20, 2010 Cathy De Rosa OCLC Global Vice President of Marketing Advocacy Awards Our Discussion • An overview a few of the current OCLC public purpose activities • A view of how these activities fit and support OCLC’s public purpose • A dialogue on the future direction and shape of your cooperative’s public purpose activities • Impact Services and Service ―When you combine advocacy, programs and services, you gain more traction against the problems you are trying to solve.‖ – Leslie Crutchfield, co-author Forces for Good: The Six Practices of High-Impact Nonprofits. OCLC’s Public Purpose promote the evolution of library OCLC is a worldwide library cooperative, owned, governed and sustained by membersuse, since 1967. of Ourlibraries public purpose themselves is a statement of commitment and to each other—that we will work together to improve access to the informationof heldlibrarianship… in libraries around the globe, and find ways to reduce costs for libraries through collaboration. Our public purpose is to establish, maintain and operate a computerized library…all network for andthe to promotefundamentalthe evolution ofpublic library use, purpose of libraries themselves and of librarianship, and to provide processes and products for theof benefit furthering of library users ease and libraries, of access including such to objectives and use as of increasingthe ever availability-expanding of library resources body to individual of worldwide library patrons and reducing the rate-of-rise of library per-unit costs, all for the fundamental publicscientific, purpose of furthering literary ease andof access educational to and use of the ever - expanding body of worldwide scientific, literary and educational knowledgeknowledge and information. -

35Th Annual General Conference 2006

!""# $ $% && 'M)* &!""# + ,, M- . M+ M- /- - + % 0 Contents Welcome from the President of LIBER 5 Welcome from Uppsala University Library 7 LIBER Executive Board 8 Conference Programme 9 Speakers’ profiles and abstracts 14 4 July 14 5 July 18 6 July 25 7 July 35 Library visits 36 Excursion 37 List of Participants by countries and institutions 38 List of Participants in alphabetical order 42 The list was compiled from the Participants’ information to the Conference registration system List of Sponsors 54 LIBER Conference – Uppsala 2006 3 Photographs by David Carr, BnF 15 Martin Cejie Front cover, 10, 36 Marcus Marcetic 36 Raf Turander 37 Tommy Westberg 11, 36 Pereric Öberg Back cover Production: Electronic Publishing Centre, Uppsala University Print: Universitetstryckeriet, Uppsala 2006 4 LIBER Conference – Uppsala 2006 Welcome from the President of LIBER As president of LIBER I am pleased to welcome colleagues from all over Europe to the 35th Annual General Conference in Uppsala. LIBER has, judging from the records, never met in Sweden, although a former vice president back in the 1980s, Thomas Tottie, was the director of Uppsala University Library. Thomas Tottie is now retired, but he is participating in our con- ference in this, his old library. I am particularly pleased to be able to welcome not only many familiar colleagues, but also many new members and partic- ipants from all over Europe. I also warmly welcome guests from other organisations, partners, and sponsors, who all support the work of LIBER in many different ways. The meeting place of this year is the oldest university in the Nordic countries, founded in 1477, just two years ahead of my own in Copenhagen. -

Survey of Ohio Libraries and State Library Services. a Report To

REPO' T R E s UM E$ LI 000$60 ED 020 7% SERVICES. A REPORT SURVEY OF onw LIBRARIESAND STATE. LIBRARY TO THE STATE LIBRARYBOARD. BY- BLASINGAME, RALPH AND ()Twits OHIO STATE LIBRARYBOARD, COLUMBUS PUB DATE 6 EDR$ PRICE MF440.75 NC-57.72 191P. DESCRIPTORS- *PUBLIC LIBRARIES,*LIBRARY SURVEYS,*STATE LIBRARIES, *PROGRAMDEVELOPMENT, *LUNAR/SERVICES, IMPROVEMENT PROGRAMS,FINANCIAL SUPPORT,PROGRAM COORDINATION, LIBRARYPROGRAMS, LIBRARYCOOPERATION, DECENTRALIZED LIBRARYSYSTEM, CENTRALIZATION,REGIONAL PLANNING, OHIO, STUDIES ON VARIOUS USING INFORMATION FROM5 COMMISSIONED REPORT), -ASPECTS OF OHIO LIBRARIES(SUMMARIZED IN THIS QUESTIONNAIRES, AND FIELDVISITS, THIS SURVEYIS INTENDED TO AND TO PROVIDE A SERVE AS A BEGINNINGFOR" ONTINUOUS PLANNING GENERAL FRAMEWORK FORSTATE-WIDE ACTIONPROGRAMS. PROBLEM. AREAS FOR OHIO PUBLICLIBRARIES ARE SEEN AS--FINANCIAL ALLOCATION OF THE SUPPORT ,THAT CONESFROM COUNTY BY COUNTY LIBRARIANS, PUBLIC INTANGIBLES TAX,COMPLACENCY AMONG MANY BY-SCHOOL-BOARDS, A STATELIBRARY LIBRARY BOARDS-APPOINTED THAT IS ORIENTED TORURAL AREAS AND HASAN UNCLEAR RELATIONSHIP WITH STATEGOVERNMENT, AND A LACKOF COMMUNICATION IN MANY AREASOF OHIO LIBRARYSERVICE. SPECIFIC 4 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THESTATE LIBRARYINCLUDEIMPROVEMENT OF QUALITY REFERENCE ITS COLLECTIONS ANDSTAFF TO PROVIDE TO BECOME A SERVICE, EXPANSIONOF THE UNION CATALOG THE STATE, ELIMINATIONOF DIRECT BIBLIOGRAPHIC CENTER FOR OF CIRCULATION AND TRAVELING LIBRARYSERVICES, AND PROVISION LIBRARIES. GENERAL' CENTRALIZED PROCESSINGSERVICES FOR PUBLIC FOR RECOMMENDATIONS EMPHASIZETHE REGIONAL APPROACH ORGANIZATION OF SERVICE,AND THRE MAJOR AREASCF FURTHER THE FOLLOWING ORDEROF LIBRARY DEVELOPMENTARE SUGGESTED IN Of THE ROLE OF l'PRIORIT-(1) ENLARGEMENTAND CLARIFICATION AND IMPLEMENTATIONOF THE OHIOSTATE LIBRARY, (2) DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS OF EQUALIZATIONOF LIBRARY SERVICESFOR ALL THE MAJOR RESIDENTSI-AND-13)_ DEVELOPMENTOF PLANS-TO RELATE LIBRARIES TO STATE 4WIDE-NEEDS4-A-- -RESOURCES-OF-THE-CITY RELATED DOCUMENT IS LI000569, AN APPENDIXTO THIS SURVEY, RESULTS. -

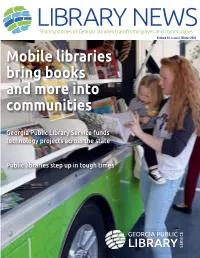

Mobile Libraries Bring Books and More Into Communities

LIBRARY NEWS Sharing stories of Georgia libraries transforming lives and communities Volume 18, Issue 2, Winter 2021 Mobile libraries bring books and more into communities Georgia Public Library Service funds technology projects across the state Public libraries step up in tough times 3 Georgia Public Library Service | georgialibraries.org | Empowering libraries to improve the lives of all Georgians Georgia public libraries step up in tough times Ben Carter By Julie Walker, state librarian for Getting digital learners and workers what they Georgia needed, fast In spring 2020, Georgia Public Library Service met As a new year begins, we look forward the urgent needs of students learning remotely. with hope to new opportunities and We purchased laptops on behalf of our libraries ways to serve our Georgia communities and assisted them in making connections to K-12 and college students who needed them. Because in 2021. I’m so proud of our library staff Georgia Public Library Service is located within across the state, who, even while librar- the University System of Georgia, we coordinat- ies were closed, found ways to help pa- ed with all 26 campus locations to quickly give trons in need of books, internet access, students without a device the tools they needed to finish their semester. and more. Their innovation inspires me every day. We heard from college students, workers, and parents with young children who were grateful for being able to borrow devices to complete I’m pleased to share some of the ways their work. that Georgia’s 411 public libraries stepped up during COVID-19. -

Nordic Languages

REFERENCE WORKS FOR THE NORDIC LANGUAGES compiled for the ATA Nordic Division Last updated on August 8, 2011 © 2011 Tollund, Inc. – Nordic Legal Language Services TABLE OF CONTENTS Danish (Monolingual).............................................................................................................. 3 Danish into English ................................................................................................................ 5 Danish into Norwegian............................................................................................................ 7 Danish into French ................................................................................................................. 7 Danish into German ............................................................................................................... 8 Danish into Swedish ............................................................................................................... 8 Danish into Latin.................................................................................................................... 8 Norwegian (Monolingual) ........................................................................................................ 9 Norwegian into English ........................................................................................................... 9 Norwegian into Danish...........................................................................................................11 Norwegian into German .........................................................................................................11 -

A Brief Look at the History of Idaho Libraries Julia Stringfellow Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Library Faculty Publications and Presentations The Albertsons Library 10-5-2012 How Did We Get Here? A Brief Look at the History of Idaho Libraries Julia Stringfellow Boise State University Presentation given at the 2012 Idaho Library Association Conference. Idaho Library Association Conference Julia Stringfellow October 5, 2012 • First library designated as the Idaho State Library. • Established in 1869. • 1890 statehood population: 88,500 people. • Formed by the Columbian Club of Boise in 1899. • Brought culture and education to 51 settlements in Idaho territory. • “This system of disseminating literature is one of the best things ever established in Idaho.” Idaho Statesman article, March 7, 1903. • Founded during 1901 Idaho Legislative Session. • Created with an annual operating budget of $3,000. • Columbian Club turned over library to the new State Library. • By the 1920s, every major city in Idaho and many smaller communities boasted a library. • Ten of those were built with Carnegie grants between 1903 and 1914: Boise, Caldwell, Idaho Falls, Lewiston, Moscow, Mountain Home, Nampa, Pocatello, Preston, and Wallace. • Member of Columbian Club that launched traveling library. • Reporter and Society Editor for the Idaho Statesman for over 30 years. • “Something of a social arbiter for the capital city” • Salary was $50 per month. • One of Idaho’s first women to serve as state school superintendent. • Taught at Boise Central School. • Part of Boise’s high society, name appears frequently in Society page of Idaho Statesman. • Extensive traveler. • First term as State Librarian. • Started at Idaho State Library in 1903. • ‘Petticoat governor of Idaho” • State population: 326,000 residents.