OCLC and the Ethics of Librarianship: Using a Critical Lens to Recast a Key Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This PDF File

Editor: Henry Reichman, California State University, East Bay Founding Editor: Judith F. Krug (1940–2009) Publisher: Barbara Jones Office for Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association ISSN 1945-4546 March 2013 Vol. LXII No. 2 www.ala.org/nif Filtering continues to be an important issue for most schools around the country. That was the message of the American Association of School Librarians (AASL), a division of the American Library Association, national longitudinal survey, School Libraries Count!, conducted between January 24 and March 4, 2012. The annual sur- vey collected data on filtering based on responses to fourteen questions ranging from whether or not their schools use filters, to the specific types of social media blocked at their schools. AASL survey The survey data suggests that many schools are going beyond the requirements set forth by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in its Child Internet Protection explores Act (CIPA). When asked whether their schools or districts filter online content, 98% of the respon- dents said content is filtered. Specific types of filtering were also listed in the survey, filtering encouraging respondents to check any filtering that applied at their schools. There were in schools 4,299 responses with the following results: • 94% (4,041) Use filtering software • 87% (3,740) Have an acceptable use policy (AUP) • 73% (3,138) Supervise the students while accessing the Internet • 27% (1,174) Limit access to the Internet • 8% (343) Allow student access to the Internet on a case-by-case basis The data indicates that the majority of respondents do use filtering software, but also work through an AUP with students, or supervise student use of online content individually. -

Worldcat Data Licensing

WorldCat Data Licensing 1. Why is OCLC recommending an open data license for its members? Many libraries are now examining ways that they can make their bibliographic records available for free on the Internet so that they can be reused and more fully integrated into the broader Web environment. Libraries may want to release catalog data as linked data, as MARC21 or as MARCXML. For an OCLC® member institution, these records may often contain data derived from WorldCat®. Coupled with a reference to the community norms articulated in WorldCat Rights and Responsibilities for the OCLC Cooperative, the Open Data Commons Attribution (ODC-BY) license provides a good way to share records that is consistent with the cooperative nature of OCLC cataloging. Best practices in the Web environment include making data available along with a license that clearly sets out the terms under which the data is being made available. Without such a license, users can never be sure of their rights to use the data, which can impede innovation. The VIAF project and the addition of Schema.org linked data to WorldCat.org records were both made available under the ODC-BY license. After much research and discussion, it was clear that ODC-BY was the best choice of license for many OCLC data services. The recommendation for members to also adopt this clear and consistent approach to the open licensing of shared data, derived from WorldCat, flowed from this experience. An OCLC staff group, aided by an external open-data licensing expert, conducted a structured investigation of available licensing alternatives to provide OCLC member institutions with guidance. -

Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt's Nineties Generation By

Writing in Cairo: Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt’s Nineties Generation by Nancy Spleth Linthicum A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein, Chair Associate Professor Samer Ali Professor Anton Shammas Associate Professor Megan Sweeney Nancy Spleth Linthicum [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9782-0133 © Nancy Spleth Linthicum 2019 Dedication Writing in Cairo is dedicated to my parents, Dorothy and Tom Linthicum, with much love and gratitude for their unwavering encouragement and support. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their invaluable advice and insights and for sticking with me throughout the circuitous journey that resulted in this dissertation. It would not have been possible without my chair, Carol Bardenstein, who helped shape the project from its inception. I am particularly grateful for her guidance and encouragement to pursue ideas that others may have found too far afield for a “literature” dissertation, while making sure I did not lose sight of the texts themselves. Anton Shammas, throughout my graduate career, pushed me to new ways of thinking that I could not have reached on my own. Coming from outside the field of Arabic literature, Megan Sweeney provided incisive feedback that ensured I spoke to a broader audience and helped me better frame and articulate my arguments. Samer Ali’s ongoing support and feedback, even before coming to the University of Michigan (UM), likewise was instrumental in bringing this dissertation to fruition. -

Mate Choice from Avicenna's Perspective

Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3240 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3259 (Online) Vol.26, 2014 Mate choice from Avicenna’s perspective 1 2 3 Masoud Raei , Maryam sadat fatemi Hassanabadi * , Hossein Mansoori 1. Assistant Professor Faculty of law and Elahiyat and Maaref Eslami, Najafabad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Najafabad, Isfahan, Iran. 2. MA Student. Fundamentals jurisprudence Islamic Law. , Islamic Azad Khorasgan University, Isfahan, Iran. 3. MA in History and Philosophy of Education, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. * E-mail of the corresponding author: hosintaghi@ gmail.com Abstract The aim of the present research was examining mate choice from Avicenna’s perspective. Being done through application of qualitative approach and a descriptive-analytic method as well, this study attempted to analyze and examine Avicenna’s perspective on effects of mate choice and on criteria for selecting an appropriate spouse and its necessities as well as the hurts discussed in this regard. The research results showed that Avicenna has encouraged all people in marriage, since it brings to them economic and social outcomes, peace and sexual satisfaction as well. Avicenna stated some criteria for appropriate mate choice, and in addition to its necessities, he advised us to follow such principles as the obvious marriage occurrence, its stability, wife’s not being common and a suitable age range for marriage. Moreover, he has examined issues and hurts related to mate choice referring to such cases as nature incongruity, marital infidelity, the state of not having any babies and ethical conflict which may happen in mate choice and marriage, suggesting some solutions to such problems. -

THIS BOOK IS OVERDUE! by Marilyn Johnson ISBN 13: 9780061431609 $24.99 Click Here for More About the Book Click Here to Pre-Order

“I have worked as a librarian for 35 years. In these pages I met the past, present, and future of my profession. Johnson knows what we know. It is great to be a librarian!” -BARBARA GENCO, Collection Development Librarian Brooklyn, NY THIS BOOK IS OVERDUE! By Marilyn Johnson ISBN 13: 9780061431609 $24.99 Click here for more about the book Click here to pre-order CHAPTER ONE “In tough times, a librarian is a terrible thing to waste.” The Frontier Down the street from the library in Deadwood, South Dakota, the peace is shattered several times a day by the noise of gunfire—just noise. The guns shoot blanks, part of a historic recreation to entertain the tourists. Deadwood is a far tamer town than it used to be, and it has been for a good long while. Its library, that emblem of civilization, is already more than a hundred years old, a Carnegie brick structure, small and dignified, with pillars outside and neat wainscoting in. The library director is Jeanette Moodie, a brisk mom in her early forties who earned her professional degree online. She’s gathering stray wineglasses from the previous night’s reception for readers and authors, in town for the South Dakota Festival of the Book. Moodie points out the portraits of her predecessors that hang in the front room. The first director started this library for her literary ladies’ club in 1895, not long after the period that gives the modern town its flavor; she looks like a proper lady, hair piled on her head, tight bodice, a choker around her neck. -

Cataloging: Search Worldcat

OCLC Connexion Client Guides Cataloging: Search WorldCat Last updated: July 2016 OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. 6565 Kilgour Place Dublin, OH 43017-3395 Revision History Date Section title Description of changes January 2008 5 Use WC Added CatL column and data to descriptions of data shown in search results WorldCat truncated and brief lists. CatL = language of cataloging 9 Retrieve local You can now define the use attribute by which to retrieve system records records (formerly, only local record number was defined) and using a Z39.50 also define structure, truncation, and relation attributes. connection August 2011 4 Qualify and Added instructions for qualifying a search by language of combine cataloging. searches 5 Use WC Clarified how printing works, depending on whether you use search results the toolbar button, the keystroke shortcut <Ctrl><P>, the File > Print command, or the hot keys <Alt><F><P>. March 2012 3 Customize WC Instructions for using the option to view WorldCat searches in search and GLIMIR clusters browse 5 Use WC Describe how GLIMIR data displays in WorldCat search results search results Can use View > List Type to toggle between GLIMIR brief and truncated lists 6 Browse WC Describes browse WorldCat results with the GLIMIR option selected With the GLIMIR option on, selecting from a browse results list results in a GLIMIR list June 2012 7 Enter WC Two examples were updated from “\bks\” to “/bks/”. batch search keys August 2013 1 Search WC Added text that states that the application supports Armenian, interactively Ethiopic, and Syriac scripts. 7 Enter WC batch search keys 10 OCLC Connexion cataloging basics July 2016 1 Search WC Removed references to institution records interactively 3 Customize WC search and browse 4 Qualify and combine searches © 2016 OCLC The following OCLC product, service and business names are trademarks or service marks of OCLC, Inc.: Connexion, OCLC, World- Cat, and "The world's libraries. -

Improving Worldcat Quality Izboljševanje Kakovosti Kataloga Worldcat

Organizacija znanja, 25 (1–2), 2020, 2025003, https://doi.org/10.3359/oz2025003 Strokovni članek / Professional article Improving WorldCat quality Izboljševanje kakovosti kataloga WorldCat Jay Weitz1 ABSTRACT: OCLC’s WorldCat approaches 475 million bibliographic records. Many of those records have been created manually by members of OCLC’s worldwide cooperative. Others have been added to WorldCat en masse from institutions large and small, from national libraries, from cultural heritage institutions, or from rural public libraries. The focus of this article is quality control of the bibliographic database, historically and currently, in four interrelated aspects: keeping OCLC-MARC validation in harmony with an ever-changing MARC 21, the specific effort to phase out OCLC-defined Encoding Levels in favour of those defined in MARC 21, a history of the automated Duplicate Detection and Resolution (DDR) software, and our work on updating Bibliographic Formats and Standards (BFAS) as reflected in Chapter 4 »When to Input a New Record«. KEYWORDS: WorldCat, OCLC-MARC, MARC 21, quality assurance, data quality control IZVLEČEK: OCLC-jev katalog WorldCat se približuje 475 milijonom bibliografskih zapisov. Veliko teh zapisov so ročno kreirali člani OCLC-jeve kooperative po vsem svetu, mnoge druge pa so v katalog WorldCat dodale velike in manjše ustanove, nacionalne knjižnice, ustanove s področja kulturne dediščine ali podeželske splošne knjižnice. Članek se osredotoča na kontrolo kakovosti bibliografske baze podatkov, in sicer s historičnega in sedanjega -

The Concept of a Work in Worldcat: an Application of FRBR

The Concept of a Work in WorldCat: An Application of FRBR Rick Bennett Office of Research OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. 6565 Frantz Road Dublin, Ohio 43017 [email protected] Brian F. Lavoie Office of Research OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. 6565 Frantz Road Dublin, Ohio 43017 [email protected] <<Please address correspondence to this author>> Edward T. O’Neill Office of Research OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. 6565 Frantz Road Dublin, Ohio 43017 [email protected] Abstract: This paper explores the concept of a work in WorldCat, the OCLC Online Union Catalog, using the hierarchy of bibliographic entities defined in the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) report. A methodology is described for constructing a sample of works by applying the FRBR model to randomly selected WorldCat records. This sample is used to estimate the number of works in WorldCat, and describe some of their key characteristics. Results suggest that the majority of benefits associated with applying FRBR to WorldCat could be obtained by concentrating on a relatively small number of complex works. Keywords: Work, FRBR, WorldCat, Bibliographic Record, Descriptive cataloging This document is an e-print version of an article published in Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 27,1 (Spring 2003). The e-print file was posted on 28 March 2003 at http://www.oclc.org/research/publications/archive/2003/lavoie_frbr.pdf. Please cite the published version. 1. Introduction The concept of a work is “an essential component of modern catalogs” [1]. And yet, much ambiguity surrounds its definition, particularly, as Smiraglia observes, in regard to “the degree to which change in ideational or semantic content represents a new work” [2]. -

Impact of Social Sciences Blog: How Information About Library Collections Represents a Treasure Trove for Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences Page 1 of 4

Impact of Social Sciences Blog: How information about library collections represents a treasure trove for research in the humanities and social sciences Page 1 of 4 How information about library collections represents a treasure trove for research in the humanities and social sciences WorldCat, an aggregate database of library catalogues worldwide, was primarily set up to aid libraries in carrying out their work in areas such as cataloguing or resource sharing. But the information it carries about much of the world’s accumulated published output is also a a unique source of information for answering a wide range of questions about world literature and other forms of creative expression. Brian Lavoie offers an insight into the types of questions WorldCat data can provide answers to, and how research of this kind also amplifies the value and impact of library collections. What is the most popular work by an Irish author? Where could one go to find out? The answer to the first question is Gulliver’s Travels. The answer to the second is WorldCat. WorldCat is an aggregate database of library catalogues, encompassing the collections of many thousands of libraries worldwide. It contains more than 425 million bibliographic records, each describing a distinct publication, and more than 2.6 billion library holdings, each indicating a particular library holding a particular publication in their collection. The publications represented in WorldCat include materials of all descriptions – books, serials, maps, recordings, etc. – and from all time periods, from ancient times to the present. WorldCat is produced and maintained by OCLC, a non-profit global library cooperative that provides shared technology services, original research, and community programmes to libraries worldwide. -

Worldcat - Your Library's Link to the World

WorldCat - Your Library's Link to the World WorldCat, begun in 1967, is the world's largest and most comprehensive database of bibliographic information. The database currently includes records from at more than 40 transportation libraries including those at UC Berkeley, Northwestern University, U.S. DOT, and libraries in state DOTs in Iowa, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Washington, among others. WorldCat includes information describing more than 2,300 Mn/DOT publications alone, along with more than 16,000 other publications held by MN/DOT Library. The full text of approximately 1,800 of these publications is directly accessible online. The database consists of standardized descriptions of books, reports, databases, articles and other information resources. It allows library staff to locate just the item you need, wherever it is, and find the most efficient and economical way of getting it for you. It also allows transportation professionals around the world to identify any of the many transportation resources currently cataloged in the database. The entire WorldCat database contains more than one billion records providing information on the locations of over 60 million books, reports, databases, magazines and other information resources. The database grows by more than one million items a year, continuously updated by staff in cooperating libraries. You can watch this updating process on their website at http://www.oclc.org/worldcat/grow.htm. WorldCat is essential to the operations of more than 57,000 libraries in 112 nations. It provides support for library cataloging, interlibrary loan, collection development and reference services. It is also testimony to the pioneering use of technology and collaborative spirit of the world's librarians. -

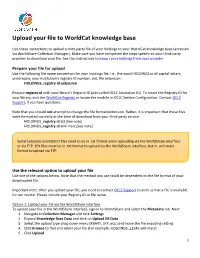

Upload Your File to Worldcat Knowledge Base

Upload your file to WorldCat knowledge base Use these instructions to upload a third-party file of your holdings to your WorldCat knowledge base (accessed via WorldShare Collection Manager). Make sure you have completed the steps specific to your third-party provider to download your file. See the instructions to export your holdings from your provider. Prepare your file for upload Use the following file name convention for your holdings file, i.e., the word HOLDINGS in all capital letters, underscore, your institution's registry ID number, dot, file extension: HOLDINGS_registry-id.extension Replace registry-id with your library's Registry ID (also called OCLC Institution ID). To locate the Registry ID for your library, visit the WorldCat Registry or locate the module in OCLC Service Configuration. Contact OCLC Support, if you have questions. Note that you should not attempt to change the file format/extension. Rather, it is important that these files were formatted correctly at the time of download from your third-party service. HOLDINGS_registry-id.txt [See note] HOLDINGS_registry-id.xml-marc [See note] Serial Solutions and EBSCO files need to be in .txt format when uploading via the WorldShare interface or via FTP. SFX files must be in .txt format to upload via the WorldShare interface, but in .xml-marc format to upload via FTP. Use the relevant option to upload your file Use one of the options below. Note that the method you use could be dependent on the file format of your downloaded file. Important note: After you upload your file, you need to contact OCLC Support to alert us that a file is available for our review. -

OCLC Developer Network Handbook

Join the OCLC Developer Network at www.oclc.org/developer. OCLC Just register or Developer log in to join! Network handbook Guide to OCLC Web Services WorldShare Web services WorldCat Basic API WorldCat Search API WorldCat knowledge base API WorldCat Registry APIs OpenURL Gateway WorldCat Identities Identifier Services (xID) QuestionPoint knowledge base Terminology Services Experimental MapFAST Web Service WorldShare Web services Note: the OCLC WorldShare Management Services (WMS) include an array of APIs, listed here as a group. WMS WMS Circulation API offers libraries a shared approach to license management, What it is: A read-only Web service so library staff can circulation and acquisitions to streamline collection generate a pull list for materials. management workflows across all formats, and create new value through cooperative analytics and shared data and What it does: Shows you which materials used need to be practices. There are 5 WorldShare Web services covered here: pulled for patron requests, holds, and digitization. 1. WMS Acquisitions API What you get: Lists of materials to be pulled at a 2. WMS Circulation API particular branch and the basic metadata to be able to retrieve the materials: title, material format, number of pieces, 3. WMS Collection Management API location and call number 4. WMS Vendor Information Center API Base Service URL: https://circ.sd00.worldcat.org/ 5. WMS NCIP Service pulllist/ For all of these services a library must subscribe to the Documentation: http://www.oclc.org/developer/ WorldShare Management Services in order to use it. The services/wms-circulation-api Query protocol is OpenSearch, record formats are XML and JSON (Atom).