Powhatan's Challenge and Opechancanough's Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

The York River: a Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1986 The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics Michael E. Bender Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Bender, M. E. (1986) The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V5JD9W This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics ·.by · Michael E. Bender .·· Virginia Institute of Marine Science School ofMar.ine Science The College of William and Mary Gloucester, Point; Virginia 23062 The York River: A Brief Review of Its Physical, Chemical and Biological Characteristics by · Michael E. Bender Virginia Institute of Marine Science School of Marine Science The College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. The York River . 5 2. The York River Basin (to the fall line) .. 6 3. Mean Daily Water Temperatures off VIMS Pier for 1954- 1977 [from Hsieh, 1979]. • . 8 4. Typical Water Temperature Profiles in the Lower York River approximately 10 km from the River Mouth . 10 5. Typical Seasonal Salinity Profiles Along the York River. -

Bladensburg Prehistoric Background

Environmental Background and Native American Context for Bladensburg and the Anacostia River Carol A. Ebright (April 2011) Environmental Setting Bladensburg lies along the east bank of the Anacostia River at the confluence of the Northeast Branch and Northwest Branch of this stream. Formerly known as the East Branch of the Potomac River, the Anacostia River is the northernmost tidal tributary of the Potomac River. The Anacostia River has incised a pronounced valley into the Glen Burnie Rolling Uplands, within the embayed section of the Western Shore Coastal Plain physiographic province (Reger and Cleaves 2008). Quaternary and Tertiary stream terraces, and adjoining uplands provided well drained living surfaces for humans during prehistoric and historic times. The uplands rise as much as 300 feet above the water. The Anacostia River drainage system flows southwestward, roughly parallel to the Fall Line, entering the Potomac River on the east side of Washington, within the District of Columbia boundaries (Figure 1). Thin Coastal Plain strata meet the Piedmont bedrock at the Fall Line, approximately at Rock Creek in the District of Columbia, but thicken to more than 1,000 feet on the east side of the Anacostia River (Froelich and Hack 1975). Terraces of Quaternary age are well-developed in the Bladensburg vicinity (Glaser 2003), occurring under Kenilworth Avenue and Baltimore Avenue. The main stem of the Anacostia River lies in the Coastal Plain, but its Northwest Branch headwaters penetrate the inter-fingered boundary of the Piedmont province, and provided ready access to the lithic resources of the heavily metamorphosed interior foothills to the west. -

Piedmont District Clubs by Counties

Piedmont District of Virginia Federation of Garden Clubs Below is a list of member Garden Clubs by county or city. Location is listed by mailing address of club president. This is not necessarily representative of all club members nor necessarily where the club holds its meeting. However, this is a good approximation. Check clubs listed in neighboring counties and cities as well. If you are interested in contacting a club please send us an email from the ‘Contact’ page and someone will be in contact with you. Thank you! Clubs by Counties Amelia -Clay Spring GC Middlesex -Amelia County GC -Hanover Herb Guild -John Mitchell GC Arlington -Hanover Towne GC -Rock Spring GC -Newfound River GC New Kent Brunswick -Old Ivy GC -Hanover Towne GC Caroline -Pamunkey River GC Charles City -West Hanover GC Northumberland -Chesapeake Bay GC Chesterfield Henrico -Kilmarnock -Bon Air GC -Crown Grant GC -Rappahannock GC -Chester GC -Ginter Park GC -Crestwood Farms GC -Green Acres GC Nottoway -Glebe Point GC -Highland Springs GC -Crewe -Greenfield GC -Hillard Park GC -Midlothian GC -Northam GC Powhatan -Oxford GC - Richmond Designers’ -Powhatan - Richmond Designers’ Guild* Guild* -River Road GC Prince William -Salisbury GC -Roslyn Hills GC -Manassas GC -Stonehenge GC -Sleepy Hollow GC -Woodland Pond GC -Thomas Jefferson GC Prince George -Windsordale GC Richmond County Cumberland -Wyndham GC Southampton -Cartersville GC Spotsylvania Dinwiddie James City -Chancellor GC Essex King and Queen -Sunlight GC Fairfax King George Fluvanna King William Stafford -Fluvanna GC Lancaster Surry Goochland Louisa -Surry GC Greensville -Lake Anna GC Sussex -Sunlight GC Westmoreland Hanover Lunenburg -Westmoreland GC -Canterbury GC Page 1 of 2 *Members of Richmond Designers’ Guild are members of other garden clubs and are from all areas. -

James River Geography

James River Geography Welcome to NOAA's James River Interpretive Buoy, located at latitude 37 degrees 12.25 minutes North, longitude 76 degrees 46.65 minutes West. It lies off Jamestown Island about a quarter-mile south of Captain John Smith's statue, where he can see it well as he looks out over the river. This buoy is anchored in 43 feet of water at the edge of the narrow shoal that runs along the island. The river's channel is deep here, as the James narrows down between Swanns Point on the south and Jamestown on the north, but it quickly shoals as it sweeps through the broad meander curve from Cobham Bay around Hog Island and down toward Burwell Bay. The buoy lies about thirty miles above the mouth of the James at Hampton Roads. Jamestown Island lies at a transition point on the James. Five miles upstream is the mouth of the Chickahominy River, which adds a strong current of fresh water to the heavy flow already coming out of the James watershed from deep in Virginia's uplands, the mountains at the eastern edge of the Alleghany Plateau. In wet years, the water here is nearly fresh. The mouth of the James, however, lies close to the Chesapeake's mouth, so salt water can also flow upriver with the tides. In John Smith's time here, the region suffered a multi-year drought, so the river and the colonists' drinking water was probably brackish, an irritating factor that may account for some of the bickering and poor health that plagued them. -

Proposed Finding

This page is intentionally left blank. Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) Proposed Finding Proposed Finding The Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 Regulatory Procedures .............................................................................................1 Administrative History.............................................................................................2 The Historical Indian Tribe ......................................................................................4 CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR 83.7) ..............................................9 Criterion 83.7(a) .....................................................................................................11 Criterion 83.7(b) ....................................................................................................21 Criterion 83.7(c) .....................................................................................................57 Criterion 83.7(d) ...................................................................................................81 Criterion 83.7(e) ....................................................................................................87 Criterion 83.7(f) ...................................................................................................107 -

Werowocomoco Was Principal Residence of Powhatan

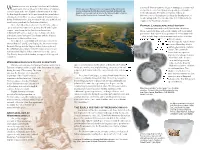

erowocomoco was principal residence of Powhatan, afterwards Werowocomoco began to emerge as a ceremonial paramount chief of 30-some Indian tribes in Virginia’s A bird’s-eye view of Werowocomoco as it appears today in Gloucester W and political center for Algonquian-speaking communities coastal region at the time English colonists arrived in 1607. County. Bordered by the York River, Leigh Creek (left) and Bland Creek (right), the archaeological site is listed on the National Register of Historic in the Chesapeake. The process of place-making at Archaeological research in the past decade has revealed not Places and the Virginia Historic Landmarks Register. Werowocomoco likely played a role in the development of only that the York River site was a uniquely important place social ranking in the Chesapeake after A.D. 1300 and in the during Powhatan’s time, but also that its role as a political and origins of the Powhatan chiefdom. social center predated the Powhatan chiefdom. More than 60 artifacts discovered at Werowocomoco Power, Landscape and History – projectile points, stone tools, pottery sherds and English Landscapes associated with Amerindian chiefdoms – copper – are shown for the fi rst time at Jamestown that is, regional polities with social ranking and institutional Settlement with archaeological objects from collections governance that organized a population of several thousand of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation and the Virginia – often include large-scale or monumental architecture that Department of Historic Resources. transformed space within sacropolitical centers. Developed in cooperation with Werowocomoco site Throughout the Chesapeake region, Native owners Robert F. and C. Lynn Ripley, the Werowocomoco communities constructed boundary ditches Research Group and the Virginia Indian Advisory Board, and enclosures within select towns, marking the exhibition also explores what Werowocomoco means spaces in novel ways. -

Virginia Indians; Powhatan, Pocahontas, and European Contact

Virginia Indians; Powhatan, Pocahontas, and European Contact HistoryConnects is made possible by the Hugh V. White Jr. Outreach Education Fund Table of Contents Virginia Indians; Powhatan, Pocahontas, and European Contact Teacher Guide Introduction/Program Description ............................................................. 3 Lesson Plan ................................................................................................. 4-7 Historical Background................................................................................ 8-9 Activities: Pre Lesson Activity: The Historical Record............................................ 10-12 During Lesson Activity: Vocab Sheet........................................................... 13 Post Lesson Activity: Pocahontas................................................................. 14 Suggested Review Questions......................................................................... 15 Student Worksheets Word Search.................................................................................................. 16 Algonquian Language Worksheet........................................................... 17-18 Selected Images/Sources Map of Virginia............................................................................................. 20 Images of Pocahontas............................................................................... 21-23 2 Introduction Thank you for showing interest in a HistoryConnects program from the Virginia Historical Society. We are really excited -

The Lincoln- Mcclellan Relationship in Myth and Memory

The Lincoln- McClellan Relationship in Myth and Memory MARK GRIMSLEY Like many Civil War historians, I have for many years accepted invita- tions to address the general public. I have nearly always tried to offer fresh perspectives, and these have generally been well received. But almost invariably the Q and A or personal exchanges reveal an affec- tion for familiar stories or questions. (Prominent among them is the query “What if Stonewall Jackson had been present at Gettysburg?”) For a long time I harbored a private condescension about this affec- tion, coupled with complete incuriosity about what its significance might be. But eventually I came to believe that I was missing some- thing important: that these familiar stories, endlessly retold in nearly the same ways, were expressions of a mythic view of the Civil War, what the amateur historian Otto Eisenschiml memorably labeled “the American Iliad.”1 For Eisenschiml “the American Iliad” was merely a clever title for a compendium of eyewitness accounts of the conflict, but I take the term seriously. In Homer’s Iliad the anger of Achilles, the perfidy of Agamemnon, the doomed gallantry of Hector—and the relationships between them—have enormous, uncontested, unchanging, and almost primal symbolic meaning. So too do certain figures in the American Iliad. Prominent among these are the butcher Grant, the Christ-like Lee, and the rage- filled Sherman. I believe that the traditional Civil War narrative functions as a national myth of central importance to our understanding of ourselves as Americans. And like the classic mythologies of old, it contains timeless wisdom about what it means to be a human being. -

Success Stories

SUCCESS STORIES PLANT NAME AND LOCATION YORK RIVER TREATMENT PLANT (HAMPTON ROADS SANITATION DISTRICT) - YORK RIVER, VA DESIGN DAILY FLOW / PEAK FLOW 0.5 MGD (1893 M3/DAY) / 0.5 MGD (1893 M3/DAY) AQUA-AEROBIC SOLUTION SINGLE-BASIN AquaSBR® SYSTEM, 4-DISK AquaDisk® FILTER AQUA-AEROBIC TECHNOLOGIES CHOSEN FOR FIRST MUNICIPAL- INDUSTRIAL WATER REUSE PROJECT IN VIRGINIA! Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD) was created in 1940 to reduce pollution in the Chesapeake Bay. It currently serves a population of approximately 1.6 million with nine regional wastewater treatment plants in Hampton Roads and four smaller plants on Virginia’s Middle Peninsula. HRSD set the goal to reuse its treated wastewater for nonpotable purposes in the 1980s. An oil refi nery located next to their York River Treatment Plant (YRTP) approached HRSD in 1996 to supply reclaimed water for the refi nery’s cooling and process water. Previously, the refi nery utilized increasingly expensive potable water and upgrading its own treatment facilities was too large an investment. In December 2000, HRSD signed a 20-year agreement to provide the refi nery with 0.5 MGD of reclaimed water. This was Virginia’s fi rst municpal-industrial water reuse project! York River’s AquaSBR® basin in operation. Since the existing activated sludge treatment process at water can be fed to the AquaDisk fi lter from either the full- HRSD’s York River Treatment Plant couldn’t reliably meet the scale plant effl uent or the sidestream AquaSBR system. refi nery’s special target requirements for both low turbidity and year-round ammonia concentration, other treatment HRSD sells the reclaimed water to the refi nery at cost, processes had to be investigated. -

EPA Interim Evaluation of Virginia's 2016-2017 Milestones

Interim Evaluation of Virginia’s 2016-2017 Milestones Progress June 30, 2017 EPA INTERIM EVALUATION OF VIRGINIA’s 2016-2017 MILESTONES As part of its role in the accountability framework, described in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (Bay TMDL) for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing this interim evaluation of Virginia’s progress toward meeting its statewide and sector-specific two-year milestones for the 2016-2017 milestone period. In 2018, EPA will evaluate whether each Bay jurisdiction achieved the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) partnership goal of practices in place by 2017 that would achieve 60 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions necessary to achieve applicable water quality standards in the Bay compared to 2009. Load Reduction Review When evaluating 2016-2017 milestone implementation, EPA is comparing progress to expected pollutant reduction targets to assess whether statewide and sector load reductions are on track to have practices in place by 2017 that will achieve 60 percent of necessary reductions compared to 2009. This is important to understand sector progress as jurisdictions develop the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIP). Loads in this evaluation are simulated using version 5.3.2 of the CBP partnership Watershed Model and wastewater discharge data reported by the Bay jurisdictions. According to the data provided by Virginia for the 2016 progress run, Virginia is on track to achieve its statewide 2017 targets for nitrogen and phosphorus but is off track to meet its statewide targets for sediment. The data also show that, at the sector scale, Virginia is off track to meet its 2017 targets for nitrogen reductions in the Agriculture, Urban/Suburban Stormwater and Septic sectors and is also off track for phosphorus in the Urban/Suburban Stormwater sector, and off track for sediment in the Agriculture and Urban/Suburban Stormwater sectors. -

Living with the Indians.Rtf

Living With the Indians Introduction Archaeologists believe the American Indians were the first people to arrive in North America, perhaps having migrated from Asia more than 16,000 years ago. During this Paleo time period, these Indians rapidly spread throughout America and were the first people to live in Virginia. During the Woodland period, which began around 1200 B.C., Indian culture reached its highest level of complexity. By the late 16th century, Indian people in Coastal Plain Virginia, united under the leadership of Wahunsonacock, had organized themselves into approximately 32 tribes. Wahunsonacock was the paramount or supreme chief, having held the title “Powhatan.” Not a personal name, the Powhatan title was used by English settlers to identify both the leader of the tribes and the people of the paramount chiefdom he ruled. Although the Powhatan people lived in separate towns and tribes, each led by its own chief, their language, social structure, religious beliefs and cultural traditions were shared. By the time the first English settlers set foot in “Tsenacommacah, or “densely inhabited land,” the Powhatan Indians had developed a complex culture with a centralized political system. Living With the Indians is a story of the Powhatan people who lived in early 17th-century Virginia—their social, political, economic structures and everyday life ways. It is the story of individuals, cultural interactions, events and consequences that frequently challenged the survival of the Powhatan people. It is the story of how a unique culture, through strong kinship networks and tradition, has endured and maintained tribal identities in Virginia right up to the present day.