Teaching the Odyssey Lesson 9: Lecture on Homer: “The Cattle of with Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Copyright by Jacqueline Kay Thomas 2007

Copyright by Jacqueline Kay Thomas 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Jacqueline Kay Thomas certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: APHRODITE UNSHAMED: JAMES JOYCE’S ROMANTIC AESTHETICS OF FEMININE FLOW Committee: Charles Rossman, Co-Supervisor Lisa L. Moore, Co-Supervisor Samuel E. Baker Linda Ferreira-Buckley Brett Robbins APHRODITE UNSHAMED: JAMES JOYCE’S ROMANTIC AESTHETICS OF FEMININE FLOW by Jacqueline Kay Thomas, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2007 To my mother, Jaynee Bebout Thomas, and my father, Leonard Earl Thomas in appreciation of their love and support. Also to my brother, James Thomas, his wife, Jennifer Herriott, and my nieces, Luisa Rodriguez and Madeline Thomas for providing perspective and lots of fun. And to Chukie, who watched me write the whole thing. I, the woman who circles the land—tell me where is my house, Tell me where is the city in which I may live, Tell me where is the house in which I may rest at ease. —Author Unknown, Lament of Inanna on Tablet BM 96679 Acknowledgements I first want to acknowledge Charles Rossman for all of his support and guidance, and for all of his patient listening to ideas that were creative and incoherent for quite a while before they were focused and well-researched. Chuck I thank you for opening the doors of academia to me. You have been my champion all these years and you have provided a standard of elegant thinking and precise writing that I will always strive to match. -

The Cyclops in the Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts

THE CYCLOPS IN THE ODYSSEY, ULYSSES, AND ASTERIOS POLYP: HOW ALLUSIONS AFFECT MODERN NARRATIVES AND THEIR HYPOTEXTS by DELLEN N. MILLER A THESIS Presented to the Department of English and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts December 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Dellen N. Miller for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of English to be taken December 2016 Title: The Cyclops in The Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts Approved: _________________________________________ Paul Peppis The Odyssey circulates throughout Western society due to its foundation of Western literature. The epic poem thrives not only through new editions and translations but also through allusions from other works. Texts incorporate allusions to add meaning to modern narratives, but allusions also complicate the original text. By tying two stories together, allusion preserves historical works and places them in conversation with modern literature. Ulysses and Asterios Polyp demonstrate the prevalence of allusions in books and comic books. Through allusions to both Polyphemus and Odysseus, Joyce and Mazzucchelli provide new ways to read both their characters and the ancient Greek characters they allude to. ii Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank Professors Peppis, Fickle, and Bishop for your wonderful insight and assistance with my thesis. Thank you for your engaging courses and enthusiastic approaches to close reading literature and graphic literature. I am honored that I may discuss Ulysses and Asterios Polyp under the close reading practices you helped me develop. -

1 Name 2 Zeus in Myth

Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus (English pronunciation: /ˈzjuːs/[3] ZEWS); Ancient Greek Ζεύς Zeús, pronounced [zdeǔ̯s] in Classical Attic; Modern Greek: Δίας Días pronounced [ˈði.as]) is the god of sky and thunder and the ruler of the Olympians of Mount Olympus. The name Zeus is cognate with the first element of Roman Jupiter, and Zeus and Jupiter became closely identified with each other. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort The Chariot of Zeus, from an 1879 Stories from the Greek is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Tragedians by Alfred Church. Aphrodite by Dione.[4] He is known for his erotic es- capades. These resulted in many godly and heroic offspring, including Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Hermes, the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, also [10][11] Persephone (by Demeter), Dionysus, Perseus, Heracles, called *Dyeus ph2tēr (“Sky Father”). The god is Helen of Troy, Minos, and the Muses (by Mnemosyne); known under this name in the Rigveda (Vedic San- by Hera, he is usually said to have fathered Ares, Hebe skrit Dyaus/Dyaus Pita), Latin (compare Jupiter, from and Hephaestus.[5] Iuppiter, deriving from the Proto-Indo-European voca- [12] tive *dyeu-ph2tēr), deriving from the root *dyeu- As Walter Burkert points out in his book, Greek Religion, (“to shine”, and in its many derivatives, “sky, heaven, “Even the gods who are not his natural children address [10] [6] god”). -

Penelope, Odysseus, and the Teleologies of the Odyssey

Putting an End to Song: Penelope, Odysseus, and the Teleologies of the Odyssey Emily Hauser Helios, Volume 47, Number 1, Spring 2020, pp. 39-69 (Article) Published by Texas Tech University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/hel.2020.0001 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/765967 [ Access provided at 28 Dec 2020 07:35 GMT from University of Washington @ Seattle ] Putting an End to Song: Penelope, Odysseus, and the Teleologies of the Odyssey EMILY HAUSER Abstract Book 1 of the Odyssey presents us with the first bard-figure of the poem, singing what in many ways is an analogue to the Odyssey with “the return of the Greeks”; yet when Penelope appears, it is to attempt to put an end to his song. I use this scene as a starting point to suggest that Penelope is deeply implicated in narrative endings in the Odyssey. Looking at the end or τέλος of the poem through a system- atic study of its “closural allusions,” I argue that a teleological analysis of Penelope’s character in relation to endings may both resolve some of the issues in her inter- pretation thus far, and open up new avenues for the reading of the Odyssey as a poem informed by endings. I. Introduction Penelope’s first appearance in the Odyssey (1.325–144) is to make a request of Phe- mius the bard, who is singing the tale of the Greeks’ return from Troy, the Ἀχαιῶν νόστος (1.326). Phemius’s song of the Greek νόστος (return), of course, mirrors the plot of the Odyssey itself, which has opened only a few hundred lines before with the plea to the Muse to sing of Odysseus and his companions’ return (νόστος, 1.5) from Troy.1 Penelope, however, interrupts the narrative flow and asks the bard to cease singing because of the pain his tale is causing her (1.340–342): ‘ταύτης δ᾽ ἀποπαύε᾽ ἀοιδῆς λυγρῆς, ἥ τέ μοι αἰεὶ ἐνὶ στήθεσσι φίλον κῆρ τείρει . -

Back-To-Back Synopses.Indd

Storykit: Back-to-back Synopses Short Synopsis (in 3s!) for ease of memorisation: The Wooden Horse 1. The Greeks go to war with the Trojans. 2. Odysseus comes up with the Wooden Horse ploy. 3. The Greeks win the war. The Ciconians 1. They are brought to the Ciconian shores by a freak wind. 2. The Greeks attack them because they were allies of Troy. 3. The Ciconians attack them back and the Greeks are forced to retreat. The Lotus Eaters 1. Arrive on a wooded isle and lose a searching-garrison. 2. Go in search and find them drinking the juice of happiness and forgetting. 3. Just get away before they are all stuck on the island under the influence of the juice. The Cyclops 1. Arrive on a barren island and search it. 2. Find the home of the Cyclops and are trapped in it. 3. Odysseus (‘Nobody’) tricks his way out, blinding the Cyclops, and they just escape. http://education.worley2.continuumbooks.com © Peter Worley (2012) The If Odyseey. London: Bloomsbury Illustrations © Tamar Levi 2012 Aeolus 1. Arrive on a fortified island and are finally welcomed as guests. 2. Odysseus is given a bag as a gift by Aeolus. 3. Crew mutiny just as they reach home and release the winds from inside the bag, blowing them back out to sea. The Laestrygonians 1. Arrive on another island with an encircled harbour. 2. Find out the hard way that this is an island of giant cannibals. 3. They only just escaped with their lives. Circe 1. Arrive on yet another island only for some of the men to be turned into pigs by the goddess Circe. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA. -

Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and Was Thought of As the Personification of Cyclic Law, the Causal Power of Expansion, and the Angel of Miracles

Ζεύς The Angel of Cycles and Solutions will help us get back on track. In the old schools this angel was known as Jupiter (Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and was thought of as the personification of cyclic law, the Causal Power of expansion, and the angel of miracles. Price, John Randolph (2010-11-24). Angels Within Us: A Spiritual Guide to the Twenty-Two Angels That Govern Our Everyday Lives (p. 151). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Zeus 1 Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus God of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, order, justice [1] The Jupiter de Smyrne, discovered in Smyrna in 1680 Abode Mount Olympus Symbol Thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak Consort Hera and various others Parents Cronus and Rhea Siblings Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter Children Aeacus, Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Dardanus, Dionysus, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces [2] Roman equivalent Jupiter Zeus (Ancient Greek: Ζεύς, Zeús; Modern Greek: Δίας, Días; English pronunciation /ˈzjuːs/[3] or /ˈzuːs/) is the "Father of Gods and men" (πατὴρ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν τε, patḕr andrōn te theōn te)[4] who rules the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father rules the family according to the ancient Greek religion. He is the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. Zeus is etymologically cognate with and, under Hellenic influence, became particularly closely identified with Roman Jupiter. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Aphrodite by Dione.[5] He is known for his erotic escapades. -

A Dictionary of Mythology —

Ex-libris Ernest Rudge 22500629148 CASSELL’S POCKET REFERENCE LIBRARY A Dictionary of Mythology — Cassell’s Pocket Reference Library The first Six Volumes are : English Dictionary Poetical Quotations Proverbs and Maxims Dictionary of Mythology Gazetteer of the British Isles The Pocket Doctor Others are in active preparation In two Bindings—Cloth and Leather A DICTIONARY MYTHOLOGYOF BEING A CONCISE GUIDE TO THE MYTHS OF GREECE AND ROME, BABYLONIA, EGYPT, AMERICA, SCANDINAVIA, & GREAT BRITAIN BY LEWIS SPENCE, M.A. Author of “ The Mythologies of Ancient Mexico and Peru,” etc. i CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1910 ca') zz-^y . a k. WELLCOME INS77Tint \ LIBRARY Coll. W^iMOmeo Coll. No. _Zv_^ _ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INTRODUCTION Our grandfathers regarded the study of mythology as a necessary adjunct to a polite education, without a knowledge of which neither the classical nor the more modem poets could be read with understanding. But it is now recognised that upon mythology and folklore rests the basis of the new science of Comparative Religion. The evolution of religion from mythology has now been made plain. It is a law of evolution that, though the parent types which precede certain forms are doomed to perish, they yet bequeath to their descendants certain of their characteristics ; and although mythology has perished (in the civilised world, at least), it has left an indelible stamp not only upon modem religions, but also upon local and national custom. The work of Fruger, Lang, Immerwahr, and others has revolutionised mythology, and has evolved from the unexplained mass of tales of forty years ago a definite and systematic science. -

Hephaestus the Magician and Near Eastern Parallels for Alcinous' Watchdogs , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28:3 (1987:Autumn) P.257

FARAONE, CHRISTOPHER A., Hephaestus the Magician and Near Eastern Parallels for Alcinous' Watchdogs , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28:3 (1987:Autumn) p.257 Hephaestus the Magician and Near Eastern Parallels for Alcinous' Watchdogs Christopher A. Faraone s ODYSSEUS enters the palace of the Phaeacian king he stops to A marvel at its richly decorated fa9ade and the gold and silver dogs that stand before it (Od. 7.91-94): , ~,t: I () \, I , ")" XPVCHLOL u EKanp E KaL apyvpEoL KVVES l1CTav, C 'll I 'll ovs'" ·'HA-.'t'aLCTTOS' ETEV~" EV LuVL?1CTL 7rpa7rLUECTCTL oWJJ.a <pvAaCTCTEJJ.EvaL JJ.EyaA~TopoS' ' AAKWOOLO, a'() avaTOVS'I OVTaS'" KaL\ aYl1pwS'')',' l1JJ.aTa 7raVTa.I On either side [sc. of the door] there were golden and silver dogs, immortal and unaging forever, which Hephaestus had fashioned with cunning skill to protect the home of Alcinous the great hearted. All the scholiasts give the same euhemerizing interpretation: the dogs were statues fashioned so true to life that they seemed to be alive and were therefore able to frighten away any who might attempt evil. Eustathius goes on to suggest that the adjectives 'undying' and 'un aging' refer not literally to biological life, but rather to the durability of the rust-proof metals from which they were fashioned, and that the dogs were alleged to be the work of Hephaestus solely on account of their excellent workmanship. 1 Although similarly animated works of Hephaestus appear elsewhere in Homer, such as the golden servant girls at Il. 18.417-20, modern commentators have also been reluctant to take Homer's description of these dogs at face value. -

A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum Cornelia G. Harcum To cite this article: Cornelia G. Harcum (1921) A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum, The Art Bulletin, 4:2, 45-58, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.1921.11409714 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1921.11409714 Published online: 22 Dec 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Download by: [Nanyang Technological University] Date: 09 May 2016, At: 01:43 Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 01:43 09 May 2016 '\'O HO S T O , \{ O YAI .OS T AH( O :'II u. ·n:u ~ ( 0'" ,\ 11 ( '11,1-:0 1.0 <:\': r .: s us TIn: :'\IOTIIEII A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal On tario Museum By CORNELIA G. HARCUM IN 1909 the Royal Ontario Museum of Archreology acquired a Parian marble statue, which came originally from the mainland of Greece, and with its basis is just six feet high. It was presented to the museum by Sigmund Samuel, Esq. The woman, or goddess (PI. IX), stands majestically with weight resting on her right foot, her right hip projecting, her left knee bent and slightly advanced. She looks in the direction of the free foot. The position gives the impression of perfect repose yet of the possibility of perfect freedom and ease of motion. -

Unit 5: Epic and Myth

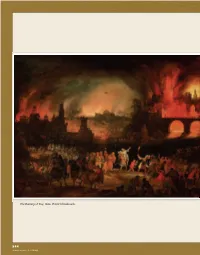

The Burning of Troy, 1606. Pieter Schoubroeck. 944 Archivo Iconografico, S.A./CORBIS UNIT FIVE Epic and Myth Looking Ahead Many centuries ago, before books, magazines, paper, and pencils were invented, people recited their stories. Some of the stories they told offered explanations of natural phenomena, such as thunder and lightning, or the culture’s customs or beliefs. Other stories were meant for entertainment. Taken together, these stories—these myths, epics, and legends—tell a history of loyalty and betrayal, heroism and cowardice, love and rejection. In this unit, you will explore the literary elements that make them unique. PREVIEW Big Ideas and Literary Focus BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 1 Journeys Hero BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 2 Courage and Cleverness Archetype OBJECTIVES In learning about the genres of epic and myth, • identifying and exploring literary elements you will focus on the following: significant to the genres • understanding characteristics of epics and myths • analyzing the effect that these literary elements have upon the reader 945 Genre Focus: Epic and Myth What is unique about epics and myths? Why do we read stories from the distant past? answer. He thought that in order for us to under- Why should we care about heroes and villains long stand the people we are today, we have to learn dead? About cities and palaces that were destroyed about those who came before us. One way to do centuries before our time? The noted psychologist that, Jung believed, was to read the myths and and psychiatrist Carl Jung thought he knew the epics of long ago.