Oxford University Working Papers in Linguistics, Philology & Phonetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umbria from the Iron Age to the Augustan Era

UMBRIA FROM THE IRON AGE TO THE AUGUSTAN ERA PhD Guy Jolyon Bradley University College London BieC ILONOIK.] ProQuest Number: 10055445 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10055445 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis compares Umbria before and after the Roman conquest in order to assess the impact of the imposition of Roman control over this area of central Italy. There are four sections specifically on Umbria and two more general chapters of introduction and conclusion. The introductory chapter examines the most important issues for the history of the Italian regions in this period and the extent to which they are relevant to Umbria, given the type of evidence that survives. The chapter focuses on the concept of state formation, and the information about it provided by evidence for urbanisation, coinage, and the creation of treaties. The second chapter looks at the archaeological and other available evidence for the history of Umbria before the Roman conquest, and maps the beginnings of the formation of the state through the growth in social complexity, urbanisation and the emergence of cult places. -

The Open-Mouthed Condition: Odysseus’ Transition from Warrior to Ruler

Sund 1 The Open-Mouthed Condition: Odysseus’ Transition from Warrior to Ruler By S. Asher Sund, M.A. Every text has a background. To know where one stands not only in his or her story but also in relation to the subtext is to know, in essence, under which god one consciously lives. This (albeit simplified) process of post-Jungian archetypal psychology of seeing through any experience to the god at core might be equally understood in terms of figurative language, and most particularly metaphor. Metaphor in Greek means “to transfer” or to “carry over” and when we get stuck in any one story (or on any one side of the sentence), we miss the subtexts (sub- gods), and lose our ability to make effective transitions. Thus we find our hero, Odysseus, staring out at sea, trapped on the paradisiacal island of Ogygia with the queenly nymph Calypso (“cover”). The problem here is not with Calypso— Odysseus concedes her beauty above all others, including his long-waiting Penelope—but with her promise of immortality. Odysseus’ epic prototype Gilgamesh, in questing after immortality, will meet up for a beer with Siduri, the tavern-keeper goddess at the edge of the world, who will tell him to give up on the possibility of immortality and to live life to the fullest every day—the best any mortal can hope for. Unlike Gilgamesh, Odysseus will find immortality, but the larger truth—more so than Siduri’s carpe diem—is that immortality is a stuck place, too, if not the most stuck place of all. -

Document Joint 1 Résolution 1 Amendements De Manille À L'annexe De La Convention Internationale De 1978 Sur Les Normes De

DOCUMENT JOINT 1 RÉSOLUTION 1 AMENDEMENTS DE MANILLE À L'ANNEXE DE LA CONVENTION INTERNATIONALE DE 1978 SUR LES NORMES DE FORMATION DES GENS DE MER, DE DÉLIVRANCE DES BREVETS ET DE VEILLE (CONVENTION STCW) LA CONFÉRENCE DE MANILLE (2010), RAPPELANT l'article XII 1) b) de la Convention internationale de 1978 sur les normes de formation des gens de mer, de délivrance des brevets et de veille (ci-après dénommée "la Convention") concernant la procédure d'amendement par une conférence des Parties, AYANT EXAMINÉ les amendements de Manille à l'Annexe de la Convention qui ont été proposés et diffusés aux Membres de l'Organisation et à toutes les Parties à la Convention, 1. ADOPTE, conformément à l'article XII 1) b) ii) de la Convention, les amendements à l'Annexe de la Convention dont le texte figure en annexe à la présente résolution; 2. DÉCIDE que, conformément à l'article XII 1) a) vii) de la Convention, les amendements qui figurent en annexe seront réputés avoir été acceptés le 1er juillet 2011 à moins que, avant cette date, plus d'un tiers des Parties à la Convention, ou des Parties dont les flottes marchandes représentent au total 50 % au moins du tonnage brut de la flotte mondiale des navires de commerce d'une jauge brute égale ou supérieure à 100, n'aient notifié au Secrétaire général qu'elles élèvent une objection contre ces amendements; 3. INVITE les Parties à noter que, conformément à l'article XII 1) a) ix) de la Convention, les amendements qui figurent en annexe entreront en vigueur le 1er janvier 2012 lorsqu'ils seront réputés avoir été acceptés dans les conditions prévues au paragraphe 2 ci-dessus; - 2 - 4. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Ilha do Desterro ISSN: 2175-8026 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Harper, Margaret Dobbs and the Tiger: The Yeatses’ Intimate Occult Ilha do Desterro, vol. 71, no. 2, 2018, May-August, pp. 205-218 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina DOI: 10.5007/2175-8026.2018v71n2p205 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478359431013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2018v71n2p205 DOBBS AND THE TIGER: THE YEATSES’ INTIMATE OCCULT Margaret Harper* University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland Abstract he mediumistic relationship between W. B. Yeats and his wife George (née Hyde Lees) is an important guide to the creative work produced by the Irish poet ater their marriage in 1917. heir unusual collaboration illuminates the esoteric philosophy expounded in the two very diferent versions of Yeats’s book A Vision (1925 and 1937). It is also theoretically interesting in itself, not only in the early period when the automatic experiments produced the “system” expounded in A Vision, but also in the 1920s and 1930s, when the Yeatses’ relationship had matured into an astonishingly productive mature partnership. his essay analyses symbols the Yeatses themselves used to conceive of their joint work, particularly the symbolic structures and constructed selves of the collaborators, and particularly in the later period. he authors’ own terminology and understanding shed light on their joint authorship; that collaboration produced not only texts but also meaning, as can be seen by the example of the poem “Michael Robartes and the Dancer.” Keywords: W. -

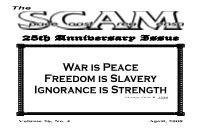

25Th Anniversary Issue

1984 April, 2008 April, 2008 —George Orwell, Orwell, —George 25th Anniversary Issue 26, No. 4 Volume The PRSRT STD U.S. Postage PAID 808 Wisteria Drive Cocoa, FL Melbourne, FL 32901-1926 32922 Permit 20 ©2008 Space Coast Area Mensa Permission to reprint non-individually copyrighted material is hereby granted to all Mensa publications, provided proper credit is given to both Author and Editor, and a separate copy of the publication is sent to both author and editor. For permission to use individually copyrighted material, contact the editor. Opinions expressed are those of the individual writers and do not reflect the opinions of Space Coast Area Mensa or American Mensa Ltd., as neither holds any opinions. Mensa is registered at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office as the collective mark of the international membership association. Send your change of address to both The SCAM at the above address and to: American Mensa Ltd., 1229 Corporate Drive West, Arlington, TX 76006-6103. The SCAM logo designed by Keith Proud ExCommunication March 5, 2008 SPACE COAST AREA MENSA Website: www.spacecoast.us.mensa.org Minutes of the ExComm Meeting: (All Area Codes are 321 except as noted) he ExComm met at the home of George Patterson on Treasurer BUD LONG T Wednesday, March 5, 2008. Called to order at 6:28 pm by Executive Committee 660 Alaska Rd., Merritt Island, FL 32953 LocSec George Patterson. Members present: George Patterson, 455-9749 [email protected] Terry Valek, and Bud Long. Thomas Wheat and Joe Smith were unable to attend. Local Secretary Recording Secretary GEORGE PATTERSON THERESA VALEK Minutes for the February 6, 2008 meeting were approved as 301 Sand Pine Rd., Indialantic, FL 32903 626-8523 published in the March 2008 SCAM. -

E Wanderings

Model the Skill ("'#!"%&# #*)&, "+!$!!#%' "!#&'('( ODiscuss the various ways that stu- *#%)!#%%#*" dents can monitor comprehen- "*" #"+%&"&&#"& sion while reading a long work * "%#('%#("''$#"'#'! such as the Odyssey: paraphras- ing, summarizing, and asking #%"#%!'#!&$&&#!*% questions. '% &""%&)"&#''"! )""'"%'#& #) O Point out that identifying causes ' '#&$'#%+&&(& and effects is an important part ('#&#"%"# "%#( of summarizing the sequence, or "&''%)"' !&#% order, of events. Explain that a ' &'#"&#*" " cause makes something happen. &$" ## An effect is what happens. OModel how to identify causes and effects in a story. Say, for example: “To identify a cause, I ask why something happened. To identify an effect, I ask what happened.” Use a simple chain-of-events chart to show the causes and effects that move the action along in Book 5. $$ '-$(%(!!$)(,'')'/''$#!")' !")''#'&#((&&##+$&!$&' Chain-of-Events Chart (&+$'#*&&()&#&$"((#,&&$#& Athena asks Zeus sends Odysseus $,,'')'+$)!!'('"''##($# Zeus to help Hermes to fi nally leaves #+1&'("(,'')'# $$ $(%' Odysseus. tell Calypso Calypso’s %&'$#&$()()!$'' !,%'$0$!'$!&'# to release island. Odysseus. '%& ''%#((#,&''*#$("' !,%'$/'#$( #(&!,)#+!!#%(*(&,#($($" 0 $'' (#'')%%$&(#!%,'')'$#' Guided Practice: Apply !$#$)&#,$+''&(&)'($!%&*$&( Guide students in identifying other "$&(!#)'&''#'("''#&$&"'($ causes and effects that propel the !,%'$/''!#($$&&,'')'&!' !($) !,%'$' action forward in Part One. Write the #$('&'*!&')(*&"'.*#&%&$"''$ events in a chain-of-events chart. -

Checklist of Philippine Chondrichthyes

CSIRO MARINE LABORATORIES Report 243 CHECKLIST OF PHILIPPINE CHONDRICHTHYES Compagno, L.J.V., Last, P.R., Stevens, J.D., and Alava, M.N.R. May 2005 CSIRO MARINE LABORATORIES Report 243 CHECKLIST OF PHILIPPINE CHONDRICHTHYES Compagno, L.J.V., Last, P.R., Stevens, J.D., and Alava, M.N.R. May 2005 Checklist of Philippine chondrichthyes. Bibliography. ISBN 1 876996 95 1. 1. Chondrichthyes - Philippines. 2. Sharks - Philippines. 3. Stingrays - Philippines. I. Compagno, Leonard Joseph Victor. II. CSIRO. Marine Laboratories. (Series : Report (CSIRO. Marine Laboratories) ; 243). 597.309599 1 CHECKLIST OF PHILIPPINE CHONDRICHTHYES Compagno, L.J.V.1, Last, P.R.2, Stevens, J.D.2, and Alava, M.N.R.3 1 Shark Research Center, South African Museum, Iziko–Museums of Cape Town, PO Box 61, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa 2 CSIRO Marine Research, GPO Box 1538, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001, Australia 3 Species Conservation Program, WWF-Phils., Teachers Village, Central Diliman, Quezon City 1101, Philippines (former address) ABSTRACT Since the first publication on Philippines fishes in 1706, naturalists and ichthyologists have attempted to define and describe the diversity of this rich and biogeographically important fauna. The emphasis has been on fishes generally but these studies have also contributed greatly to our knowledge of chondrichthyans in the region, as well as across the broader Indo–West Pacific. An annotated checklist of cartilaginous fishes of the Philippines is compiled based on historical information and new data. A Taiwanese deepwater trawl survey off Luzon in 1995 produced specimens of 15 species including 12 new records for the Philippines and a few species new to science. -

Not the Same Old Story: Dante's Re-Telling of the Odyssey

religions Article Not the Same Old Story: Dante’s Re-Telling of The Odyssey David W. Chapman English Department, Samford University, Birmingham, AL 35209, USA; [email protected] Received: 10 January 2019; Accepted: 6 March 2019; Published: 8 March 2019 Abstract: Dante’s Divine Comedy is frequently taught in core curriculum programs, but the mixture of classical and Christian symbols can be confusing to contemporary students. In teaching Dante, it is helpful for students to understand the concept of noumenal truth that underlies the symbol. In re-telling the Ulysses’ myth in Canto XXVI of The Inferno, Dante reveals that the details of the narrative are secondary to the spiritual truth he wishes to convey. Dante changes Ulysses’ quest for home and reunification with family in the Homeric account to a failed quest for knowledge without divine guidance that results in Ulysses’ destruction. Keywords: Dante Alighieri; The Divine Comedy; Homer; The Odyssey; Ulysses; core curriculum; noumena; symbolism; higher education; pedagogy When I began teaching Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 1990s as part of our new Cornerstone Curriculum, I had little experience in teaching classical texts. My graduate preparation had been primarily in rhetoric and modern British literature, neither of which included a study of Dante. Over the years, my appreciation of Dante has grown as I have guided, Vergil-like, our students through a reading of the text. And they, Dante-like, have sometimes found themselves lost in a strange wood of symbols and allegories that are remote from their educational background. What seems particularly inexplicable to them is the intermingling of actual historical characters and mythological figures. -

James Mill, “Review of M. De Guignes, Voyages À Peking

James Mill, “Review of M. de Guignes, Voyages à Peking, Manille, et l’Ile de France, faits dans l’intervalle des a nnées 1784 à 1801,” The Edinburgh Review 14 (July 1809): 407-429. the original text In the small catalogue of rational books which we possess on the subject of China, this deserves to occupy a respectable station. The recent work of Mr Barrow is that with which it is most natural for us to compare it: and, though not in all, yet, in several respects we are inclined to give it the preference to that judicious publication. The author, from long residence in the country, and from a knowledge of the language, is less new to his subject, and more master of it. He has formed a more accurate estimate than Mr Barrow, of certain important particulars in the political and social state of the Chinese. But his book is not so rich, by any means, in facts. We have the author’s own observations on the appearances which struck him; and these are often very good — but Barrow has more uniformly described to us the various phenomena which presented themselves in the course of his interesting progress. It is true, indeed, and this is what should be remembered in behalf of both, that their opportunities of observing facts, by the restrictions, or rather imprisonment, under which they were held by the pitiful policy of this illiberal and ignorant people, were extremely circumscribed. The name of De Guignes is intimately associated with that of China in the minds of all those to whom the history of the oriental nations has been an object of attention. -

First Capitals of Armenia and Georgia: Armawir and Armazi (Problems of Early Ethnic Associations)

First Capitals of Armenia and Georgia: Armawir and Armazi (Problems of Early Ethnic Associations) Armen Petrosyan Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Yerevan The foundation legends of the first capitals of Armenia and Georgia – Armawir and Armazi – have several common features. A specific cult of the moon god is attested in both cities in the triadic temples along with the supreme thunder god and the sun god. The names of Armawir and Armazi may be associated with the Anatolian Arma- ‘moon (god).’ The Armenian ethnonym (exonym) Armen may also be derived from the same stem. The sacred character of cultic localities is extremely enduring. The cults were changed, but the localities kept their sacred character for millennia. At the transition to a new religious system the new cults were often simply imposed on the old ones (e.g., the old temple was renamed after a new deity, or the new temple was built on the site or near the ruins of the old one). The new deities inherited the characteristics of the old ones, or, one may say, the old cults were simply renamed, which could have been accompanied by some changes of the cult practices. Evidently, in the new system more or less comparable images were chosen to replace the old ones: similarity of functions, rituals, names, concurrence of days of cult, etc (Petrosyan 2006: 4 f.; Petrosyan 2007a: 175).1 On the other hand, in the course of religious changes, old gods often descend to the lower level of epic heroes. Thus, the heroes of the Armenian ethnogonic legends and the epic “Daredevils of Sasun” are derived from ancient local gods: e.g., Sanasar, who obtains the 1For numerous examples of preservation of pre-Urartian and Urartian holy places in medieval Armenia, see, e.g., Hmayakyan and Sanamyan 2001). -

The Ancient People of Italy Before the Rise of Rome, Italy Was a Patchwork

The Ancient People of Italy Before the rise of Rome, Italy was a patchwork of different cultures. Eventually they were all subsumed into Roman culture, but the cultural uniformity of Roman Italy erased what had once been a vast array of different peoples, cultures, languages, and civilizations. All these cultures existed before the Roman conquest of the Italian Peninsula, and unfortunately we know little about any of them before they caught the attention of Greek and Roman historians. Aside from a few inscriptions, most of what we know about the native people of Italy comes from Greek and Roman sources. Still, this information, combined with archaeological and linguistic information, gives us some idea about the peoples that once populated the Italian Peninsula. Italy was not isolated from the outside world, and neighboring people had much impact on its population. There were several foreign invasions of Italy during the period leading up to the Roman conquest that had important effects on the people of Italy. First there was the invasion of Alexander I of Epirus in 334 BC, which was followed by that of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 280 BC. Hannibal of Carthage invaded Italy during the Second Punic War (218–203 BC) with the express purpose of convincing Rome’s allies to abandon her. After the war, Rome rearranged its relations with many of the native people of Italy, much influenced by which peoples had remained loyal and which had supported their Carthaginian enemies. The sides different peoples took in these wars had major impacts on their destinies. In 91 BC, many of the peoples of Italy rebelled against Rome in the Social War. -

150506-Woudhuizen Bw.Ps, Page 1-168 @ Normalize ( Microsoft

The Ethnicity of the Sea Peoples 1 2 THE ETHNICITY OF THE SEA PEOPLES DE ETNICITEIT VAN DE ZEEVOLKEN Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. S.W.J. Lamberts en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op vrijdag 28 april 2006 om 13.30 uur door Frederik Christiaan Woudhuizen geboren te Zutphen 3 Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof.dr. W.M.J. van Binsbergen Overige leden: Prof.dr. R.F. Docter Prof.dr. J. de Mul Prof.dr. J. de Roos 4 To my parents “Dieser Befund legt somit die Auffassung nahe, daß zumindest für den Kern der ‘Seevölker’-Bewegung des 14.-12. Jh. v. Chr. mit Krieger-Stammesgruppen von ausgeprägter ethnischer Identität – und nicht lediglich mit einem diffus fluktuierenden Piratentum – zu rechnen ist.” (Lehmann 1985: 58) 5 CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................................................................................................9 Note on the Transcription, especially of Proper Names....................................................................................................11 List of Figures...................................................................................................................................................................12 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................................................13