Engaging Foucault

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zone Na Teritoriji Grada Beograda Četvrtak, 10 Mart 2011 00:00

Zone na teritoriji Grada Beograda četvrtak, 10 mart 2011 00:00 Odlukom o određivanju zona na teritoriji Grada Beograda (Sl. list grada Beograda", br. 60/2009 i 45/2010) određene su zone kao jedan od kriterijuma za utvrđivanje visine lokalnih komunalnih taksi, naknade za korišćenje građevinskog zemljišta i naknade za uređivanje građevinskog zemljišta. Takođe, zone određene tom odlukom primenjuju se i kao kriterijum za utvrđivanje visine zakupnine za poslovni prostor na kome je nosilac prava korišćenja grad Beograd. Na teritoriji grada Beograda postoje devet zona u zavisnosti od tržišne vrednosti objekata i zemljišta, komunalne opremljenosti i opremljenosti javnim objektima, pokrivenosti planskim dokumentima i razvojnim mogućnostima lokacije, kvaliteta povezanosti lokacije sa centralnim delovima grada, nameni objekata i ostalim uslovljenostima. Spisak zona - Prva zona - U okviru prve zone nalaze se: - Zona zaštite zelenila - Područje uže zone zaštite vodoizvorišta za Beograd - Područje uže zone zaštite vodoizvorišta za naselje Obrenovac - Ekstra zona stanovanja - Ekstra zona poslovanja - Druga zona - Treća zona - Četvrta zona - Peta zona - Šesta zona - Sedma zona 1 / 25 Zone na teritoriji Grada Beograda četvrtak, 10 mart 2011 00:00 - Osma zona - Zona specifičnih namena Ovde možete preuzeti grafički prikaz zona u Beogradu. Napomene: 1. U slučaju neslaganja tekstualnog dela i grafičkog priloga, važi grafički prilog . 2. Popis katastarskih parcela i granice katastarskih opština su urađene na osnovu raspoloživih podloga i ortofoto snimaka iz -

Grada Beograda

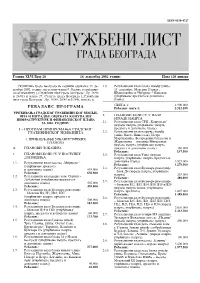

ISSN 0350-4727 SLU@BENI LIST GRADA BEOGRADA Godina XLVI Broj 28 16. decembar 2002. godine Cena 120 dinara Skup{tina grada Beograda na sednici odr`anoj 13. de- 1.8. Regulacioni plan bloka izme|u ulica: cembra 2002. godine, na osnovu ~lana 9. Odluke o gra|evin- 14. decembra, Maksima Gorkog, skom zemqi{tu („Slu`beni list grada Beograda”, br. 16/96 [umatova~ke i ^uburske – Kikevac i 26/01) i ~lana 27. Statuta grada Beograda („Slu`beni (utvr|ivawe predloga i dono{ewe list grada Beograda”, br. 18/95, 20/95 i 21/99), donela je plana) –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– SVEGA 1: 1.900.000 REBALANS PROGRAMA Rebalans svega 1: 2.312.100 –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– URE\IVAWA GRADSKOG GRA\EVINSKOG ZEMQI- [TA I IZGRADWE OBJEKATA KOMUNALNE 2. PLANOVI KOJI SU U FAZI INFRASTRUKTURE I FINANSIJSKOG PLANA IZRADE NACRTA ZA 2002. GODINU 2.1. Regulacioni plan SRC „Ko{utwak” (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, á – PROGRAM PRIPREMAWA GRADSKOG predloga i dono{ewe plana) GRA\EVINSKOG ZEMQIŠTA 2.2. Regulacioni plan podru~ja izme|u ulica: Kneza Vi{eslava, Petra 1. PRIBAVQAWE URBANISTI^KIH Martinovi}a, Beogradskih bataqona i PLANOVA @arkova~ke – lokacija Mihajlovac (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, A. PLANOVI LOKACIJA predloga i dono{ewe plana) 160.000 Rebalans: 137.500 1. PLANOVI KOJI SU U POSTUPKU 2.3. Regulacioni plan Umke (izrada DONOŠEWA nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, predloga i 1.1. Regulacioni plan naseqa „Mirijevo” dono{ewe plana) 3.925.000 (utvr|ivawe predloga Rebalans: 3.279.900 2.4. Regulacioni plan Bulevara revolucije i dono{ewe plana) 635.000 – blok D6 (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe Rebalans: 656.600 nacrta) 235.000 1.2. -

Slu@Beni List Grada Beograda

ISSN 0350-4727 SLU@BENI LIST GRADA BEOGRADA Godina XLVIII Broj 10 26. maj 2004. godine Cena 120 dinara Skup{tina grada Beograda na sednici odr`anoj 25. ma- ma stepenu obaveznosti: (a) nivo 2006. godine za planska ja 2004. godine, na osnovu ~lana 20. Zakona o planirawu i re{ewa za koja postoje argumenti o neophodnosti i opravda- izgradwi („Slu`beni glasnik RS", broj 47/03) i ~l. 11. i nosti sa dru{tvenog, ekonomskog i ekolo{kog stanovi{ta; 27. Statuta grada Beograda („Slu`beni list grada Beogra- (b) nivo 2011. godine za planske ideje za koje je oceweno da da", br. 18/95, 20/95, 21/99, 2/00 i 30/03), donela je postoji mogu}nost otpo~iwawa realizacije uz podr{ku fondova Evropske unije za kandidatske i pristupaju}e ze- REGIONALNI PROSTORNI PLAN mqe, me|u kojima }e biti i Srbija; (v) nivo iza 2011. godine, kao strate{ka planska ideja vodiqa za ona re{ewa kojima ADMINISTRATIVNOG PODRU^JA se dugoro~no usmerava prostorni razvoj i ure|ivawe teri- GRADA BEOGRADA torije grada Beograda, a koja }e biti podr`ana struktur- nim fondovima Evropske unije, ~iji }e ~lan u optimalnom UVODNE NAPOMENE slu~aju tada biti i Republika Srbija. Regionalni prostorni plan administrativnog podru~ja Planska re{ewa predstavqaju obavezu odre|enih insti- grada Beograda (RPP AP Beograda) pripremqen je prema tucija u realizaciji, odnosno okosnicu javnog dobra i javnog Odluci Vlade Republike Srbije od 5. aprila 2002. godine interesa, uz istovremenu punu podr{ku za{titi privatnog („Slu`beni glasnik RS", broj 16/02). -

Distribution of Selected Vascular Plants, Fungi, Amphibians and Reptiles in Serbia – Data from Biological Collections of the N

Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, 2019, 12: 37-84. Received 22 Jun 2019; Accepted 22 Nov 2019. doi:10.5937/bnhmb1912037J UDC: 069.51:58/59(497.11) Original scientific paper DISTRIBUTION OF SELECTED VASCULAR PLANTS, FUNGI, AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN SERBIA – DATA FROM BIOLOGICAL COLLECTIONS OF THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM IN BELGRADE IMPLEMENTED IN CURRENT NATIONAL CONSERVATION PROJECTS MIROSLAV JOVANOVIĆ, UROŠ BUZUROVIĆ, BORIS IVANČEVIĆ, ANA PAUNOVIĆ, MARJAN NIKETIĆ* Natural History Museum, Njegoševa 51, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia, e-mail: [email protected] A total of 990 records of selected vascular plants, fungi, amphibians and reptiles from biological collections of the Natural History Museum in Belgrade was reporter for Serbia. They include 34 representatives of Polypodiopsida, 32 of Pinopsida, 560 of Magnoliopsida, 127 of Pezizomycetes, 28 of Agaricomycetes, 16 of Amphibia and 13 of Reptilia. The databases contains 86 species of vascular plants, 24 species of fungi, 13 species of amphibians and 8 species of reptiles which are protected and strictly protected in Serbia. Key words: vascular flora, fungi, amphibians, reptiles, protected species, Serbia INTRODUCTION This catalog is the result of the work of authors from Natural History Museum in Belgrade who participated in the development of current 38 JOVANOVIĆ, M. ET AL.: PLANTS, FUNGI, AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES FROM SERBIA conservation projects funded by the Institute of Nature Conservation of Serbia: 1) “Obtaining data and other services in order to continue estab- lishing an ecological network in the Republic of Serbia” JNOP 01/2018; 2) “Obtaining data and other services for the purpose of establishing the eco- logical network of the European Union Natura 2000 as part of the ecological network of the Republic of Serbia” JNOP 02/2018; 3) “Data acquisition and other services for the purpose of continuing the develop- ment of Red Data Lists of individual groups of flora, fauna and fungi in the Republic of Serbia” JNOP 03/2018. -

Belgrade, Serbia Destination Guide

Belgrade, Serbia Destination Guide Overview of Belgrade Belgrade has developed into a prominent European capital, its promising growth and optimism seeking to overshadow its turbulent past. The history of Belgrade goes back some 6,000 years, and is filled with tales of conflict and tragedy. But no matter the cost or devastation, the city has always bounced back and is in the midst of a cultural and creative revival. Situated where the Sava and Danube rivers meet on the Balkan Peninsula, the beauty and charm of the city is not found in gorgeous buildings or sweeping parks. Instead, it beats with an identity layered with relics of many generations and the remaining customs of countless invaders. Decidedly Old World with a hint of the Orient, varying cultural influences and architectural styles jostle for attention in Belgrade, combining to imbue the modern city with its own unique aura. The best place to begin understanding the city is at the site of its original ancient settlement, the hill called Kalemegdan, now a fascinating park-like complex of historic structures overlooking the Old Town (Stari Grad). Here, the Military Museum traces the history of the city's bloody past, from its first conflict with the Roman legions in the 1st century BC to its most recent conflagration, when NATO forces bombed the city for 78 straight days in 1999. Those less fascinated by history and who would rather enjoy modern Belgrade will find myriad leisure and pleasure opportunities in the city. From the techno scene of its famed nightclubs to the restaurants and street performances of bohemian Skadarlija Street, visitors to Belgrade will feel welcomed by the warm and proud residents of this indomitable city. -

Transition of Collective Land in Modernistic Residential Settings in New Belgrade, Serbia

land Article Transition of Collective Land in Modernistic Residential Settings in New Belgrade, Serbia Milica P. Milojevi´c*, Marija Maruna and Aleksandra Djordjevi´c Faculty of Architecture, University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (A.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 September 2019; Accepted: 15 November 2019; Published: 16 November 2019 Abstract: Turbulent periods of transition from socialism to neoliberal capitalism, which have affected the relationships between holders of power and governing structures in Serbia, have left a lasting impact on the urban spaces of Belgrade’s cityscape. The typical assumption is that the transformation of the urban form in the post-socialist transition is induced by planning interventions which serve to legitimize these neoliberal aspirations. The methodological approach of this paper is broadly structured as a chronological case analysis at three levels: the identification of three basic periods of institutional change, historical analysis of the urban policies that permitted transformation of the subject area, and morphogenesis of the selected site alongside the Sava River in New Belgrade. Neoliberal aspirations are traced through the moments of destruction and moments of creation as locally specific manifestations of neoliberal mechanisms observable through the urban form. Comparison of all three levels of the study traces how planning and political decisions have affected strategic directions of development and, consequently, the dynamics and spatial logic of how new structures have invaded the street frontage. The paper demonstrates that planning interventions in the post-socialist transition period, guided by the neoliberal mechanisms, has had a profound impact on the super-block morphology. -

31. Decembar 2009. Broj 113 5

31. decembar 2009. Broj 113 5 SPISAK DIREKTNIH I INDIREKTNIH KORISNIKA SREDSTAVA BUXETA REPUBLIKE SRBIJE, ODNOSNO BUXETA LOKALNE VLASTI, KORISNIKA SREDSTAVA ORGANIZACIJA ZA OBAVEZNO SOCIJALNO OSIGURAWE, KAO I DRUGIH KORISNIKA JAVNIH SREDSTAVA KOJI SU UKQU^ENI U SISTEM KONSOLIDOVANOG RA^UNA TREZORA –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Grupa Naziv Mesto Org. jed. Oznaka Mati~ni Jedinstveni Uprave trezora broj broj k.b.s.* za trezor –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 12 3 456 7 –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– KORISNICI SREDSTAVA BUXETA REPUBLIKE SRBIJE 1 REPUBLIKA SRBIJA BEOGRAD 40200 601 07017715 2683 1.1 NARODNA SKUP[TINA REPUBLIKE SRBIJE BEOGRAD 40200 601 07017715 20100 1.1.1 NARODNA SKUP[TINA REPUBLIKE SRBIJE – STRU^NE SLU@BE BEOGRAD 40200 601 07017715 20101 1.2 PREDSEDNIK REPUBLIKE SRBIJE BEOGRAD 40200 601 07051344 10100 1.3.1 KABINET PREDSEDNIKA VLADE BEOGRAD 40200 601 07020171 10204 1.3.2 KABINET PRVOG POTPREDSEDNIKA VLADE BEOGRAD 40200 601 07020171 10216 1.3.3 KABINET POTPREDSEDNIKA VLADE – za oblast evropskih integracija BEOGRAD 40200 601 07020171 10205 1.3.4 KABINET POTPREDSEDNIKA VLADE – za privredni razvoj BEOGRAD 40200 601 07020171 10217 1.3.5 KABINET POTPREDSEDNIKA VLADE – za socijalnu politiku i dru{tvene -

Kvalitet Životne Sredine Grada Beograda U 2008. Godini

KVALITET ŽIVOTNE SREDINE GRADA BEOGRADA U 2008. GODINI GRADSKA UPRAVA gradA BEOgrad Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA JAVNO ZDRAVLJE REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL CENTER Beograd 2008 KVALITET ŽIVOTNE SREDINE GRADA BEOGRADA U 2008. GODINI Obrađivači: 1. Prim.dr Snežana Matić Besarabić (GZJZ) . poglavlje 1.1 2. Milica Gojković, dipl. inž . 3. Vojislava Dudić, dipl. inž . (Institut za javno zdravlje Srbije "Dr Milan Jovanović Batut") . poglavlje 1.2 4. Mr Gordana Pantelić (Institut za medicinu rada . i radiološku zaštitu "Dr Dragomir Karajović"). poglavlja. 1.3; 2.2; 2.5; 3.2 4. Prim. dr Miroslav Tanasković (GZJZ) . poglavlja 2.1; 2.3 5. Dr Marina Mandić (GZJZ) . poglavlje 2.4 6. Dr Dragan Pajić (GZJZ) . poglavlja 2.6; 3.1 7. Mr Predrag Kolarž, Institut za Fiziku . poglavlja 3.3 8. Boško Majstorović, dipl. inž (GZJZ) . poglavlje 4.0 9. Dr Milan Milutinović (GZJZ) . poglavlja 5.1; 5.2 Urednici: Marija Grubačević, pomoćnik sekretara, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Radomir Mijić, samostalni stručni saradnik, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Biljana Glamočić, samostalni stručni saradnik, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Branislav Božović, načelnik odeljenja, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Primarijus Miroslav Tanasković, Gradski zavod za javno zdravlje Ana Popović, dipl. inž, projekt menadžer, REC Suizdavači: Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine, Beograd Gradski zavod za javno zdravlje, Beograd Regionalni centar za životnu sredinu za Centralnu i Istočnu Evropu (REC) Za izdavače: Goran Trivan, dipl. inž, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Mr sci med Slobodan Tošović, Gradski zavod za javno zdravlje Jovan Pavlović, Regionalni centar za životnu sredinu Fotografije Da budemo na čisto preuzete iz vizuelno-edukativno-propagandnog projekta . -

61-2009- Kopija.Qxd

ISSN 0350-4727 SLU@BENI LIST GRADA BEOGRADA Godina LIII Broj 61 29. decembar 2009. godine Cena 200 dinara Skup{tina grada Beograda na sednici odr`anoj 29. de- prevozu kad usled vi{e sile do|e do smawenog obima u vr- cembra 2009. godine, na osnovu ~lana 46. Zakona o lokalnim {ewu linijskog prevoza, izborima („Slu`beni glasnik RS”, broj 129/07), donela je 7. izrada i kontrola ostvarewa reda vo`we, 8. organizacija sistema pra}ewa i upravqawa vozilima ODLUKU linijskog prevoza, 9. organizacija sistema naplate usluge prevoza, prodaje O PRESTANKU MANDATA ODBORNIKA SKUP[TINE voznih isprava, kontrole putnika i dr. GRADA BEOGRADA Organizaciona jedinica Gradske uprave nadle`na za poslove saobra}aja (u daqem tekstu: nadle`na organizaci- 1. Utvr|uje se prestanak mandata odbornika Skup{tine ona jedinica) obezbe|uje organizovano i trajno obavqawe grada Beograda Velimira Radosavqevi}a, sa izborne liste i razvoj linijskog prevoza, stara se o obezbe|ivawu ugovo- Za evropski Beograd – Boris Tadi}, pre isteka vremena na rom preuzetih obaveza, organizuje i vr{i nadzor nad oba- koje je izabran, zbog podnete ostavke. vqawem linijskog prevoza, kao i nad kori{}ewem ove ko- 2. Ovu odluku objaviti u „Slu`benom listu grada Beo- munalne usluge. grada”. Nadle`na organizaciona jedinica utvr|uje obim i kva- litet usluge linijskog prevoza u skladu sa materijalnim Skup{tina grada Beograda mogu}nostima grada, posebnim pravilnikom. Broj 118-1181/09-S, 29. decembra 2009. godine Linijski prevoz je komunalna delatnost od op{teg in- teresa. Predsednik ^lan 2. Aleksandar Anti}, s. r. Pojedini izrazi u smislu ove odluke imaju slede}a zna- ~ewa: 1. -

07 Simone Zatric

Planum. The Journal of Urbanism n.29 vol II/2014 WITHIN THE LIMITS OF SCARCITYRETHINKING SPACE, CITY AND PRACTICES Edited by Barbara Ascher Isis Nunez Ferrera Michael Klein Special Issue in collaboration with SCIBE Peer Reviewed Articles Planum. The Journal of Urbanism n.29 vol II/2014 in collaboration with SCIBE Scarcity and Creativity in the Built Environment Peer Reviewed Articles WITHIN THE LIMITS OF SCARCITY RETHINKING SPACE, CITY AND PRACTICES Edited by Barbara Ascher Isis Nunez Ferrera Michael Klein Published by Planum. The Journal of Urbanism no.29, vol. II/2014 © Copyright 2014 by Planum. The Journal of Urbanism ISSN 1723-0993 Registered by the Court of Rome on 04/12/2001 Under the number 514-2001 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trasmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Planum. The Journal of Urbanism The publication has been realized by the Editorial Staff of Planum. The Journal of Urbanism: Giulia Fini, Marina Reissner, Cecilia Saibene Graphics by Nicola Vazzoler Cover: Adapted from “Self-built housing in Quito, Ecuador © Isis Nunez Ferrera CONTENTS EDITORIAL Barbara Ascher, Isis Nunez Ferrera, Michael Klein .......................p.7 Scarcity - Local responses to “lack” Camillo Boano ......................................................................p.13 Notes around design politics: design dissensus and the poiesis of scarcity Bo Tang .................................................................................p.29 -

Analiza Tržišta Nekretnina U Srbiji IZVEŠTAJ ZA 2019. GODINU

Analiza tržišta nekretnina u Srbiji IZVEŠTAJ ZA 2019. GODINU Medijski partneri O servisu Moja Nekretnina 3 Predmet istraživanja 3 Vremenski period 3 Segmenti tržišta 4 Lokacije 4 Definicija pojmova 4 Prosečna cena kao prosta sredina 4 Srednja cena kao medijana 5 Realna prosečna cena 5 Tržište nekretnina u 2019. godini 6 Tržište nekretnina u Srbiji 6 Tržište nekretnina u Beogradu 9 Cena kvadrata - Novi Beograd 15 Cena kvadrata - Zemun 17 Cena izdavanja nekretnina u Beogradu 18 Profitabilnost izdavanja stanova u Beogradu 24 Tržište nekretnina u Novom Sadu 29 Novogradnja u 2019. godini 30 Ekonomski faktori 30 Bruto domaći proizvod 30 Prosečne zarade 31 Doznake iz inostranstva 32 Predviđanje kretanja tržišta nekretnina u 2020. godini 32 Izmene Zakona o porezu na imovinu 33 Zaključak 34 Reference 35 O servisu Moja Nekretnina Moja Nekrenina je servis za procenu vrednosti nekretnine. Na osnovu objavljenih oglasa na sajtovima za nekretnine u Srbiji, vrši se analiza kretanja cena nekretnina kao i kretanja cena izdavanja stanova. Posebna pažnja usmerena je na veće gradove kao što su Beograd, Novi Sad, Niš i Kragujevac, gde je i tržište nekretnina najdinamičnije. Moja Nekretnina nastoji da prikupi i analizira što veći broj oglašenih nekretnina na internetu, kako bi broj objavljenih nekretnina, koje ulaze u istraživanje bio što veći, a samim tim i analiza preciznija. Pored kvartalne i godišnje analize stanja tržišta nekretnina, korisnici servisa mogu u svakom trenutku besplatno da procene vrednost svoje nekretnine kao i realnu cenu izdavanja i time budu u toku sa trenutnim stanjem na tržištu nekretnina. Na ovaj način činimo tržište transparentnim i nudimo mogućnost svakome da dođe do potrebnih informacija na brz i jednostavan način. -

Belgradeinsightissueno256.Pdf

Berislav Serbetic and Vojin Bakic. Monument to the Uprising of the People of Kordun and Banija. 1979–81. Petrova Gora, Croatia. Exterior view. view. Exterior Croatia. Gora, andBanija.1979–81.Petrova ofKordun theUprisingofPeople Bakic.Monumentto Berislav SerbeticandVojin NEW YORK’S MOMA SHINES A LIGHT LIGHT A SHINES MOMA YORK’S NEW +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 Belgrade in Stone in Carved is History Serbia’s Page 6 ON SOCIALIST YUGOSLAV YUGOSLAV SOCIALIST ON A prestigious new exhibition forces a fresh afresh forces exhibition new A prestigious look at the underappreciated architecture architecture underappreciated the at look [email protected] Issue No. No. Issue ARCHITECTURE 256 of Tito’s Yugoslavia of Tito’s Friday, July 13 - Thursday, July 26, 2018 26, July 13-Thursday, July Friday, Continued on on Continued page 13 page in Serbia Monuments Must-See Five Page 10 Photo: Valentin Jeck, commissioned byTheMuseumofModernArt,2016 Jeck,commissioned Valentin Photo: BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY INSIGHTISPUBLISHED BELGRADE ORDER DELIVERY TO DELIVERY ORDER [email protected] YOUR DOOR YOUR +381 11 4030 303 114030 +381 Friday • June 13 • 2008 NEWS NEWS 1 9 7 7 1 ISSN 1820-8339 8 2 0 8 3 3 0 0 0 0 1 Issue No. 1 / Friday, June 13, 2008 EDITOR’S WORD Lure of Tadic Alliance Splits Socialists Political Predictability While younger Socialists support joining a new, pro-EU government, old By Mark R. Pullen Milosevic loyalists threaten revolt over the prospect. party over which way to turn. “The situation in the party seems extremely complicated, as we try to convince the few remaining lag- gards that we need to move out of Milosevic’s shadow,” one Socialist Party official complained.