Urban Housing Experiments in Yugoslavia 1948-1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mass-Housing: Tendencies and Modernization Research Paper

Faculty: The Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment Department: Architecture Programme: MSc programme Architecture, Urbanism and Building Sciences Studio: Explore Lab 17 Mass-Housing: Tendencies and Modernization Research paper Author: M. Šutavičius, Study number: 4254791 Email: [email protected] Mentor: Y. J. Cuperus May 2014 2 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................... 5 Method description ............................................................................................................................................ 6 2. INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. MASS-HOUSING IN SOVIET UNION ................................................................................................................... 19 Policy ................................................................................................................................................................. 20 Utopia ............................................................................................................................................................... 20 Pollution............................................................................................................................................................ 21 Construction .................................................................................................................................................... -

Dragan Kapicic Myths of the Kafana Life Secrets of the Underground

investments s e i t r e p o offices r p y r u x u l houses apartments short renting Dragan Kapicic Myths of the Kafana Life Secrets of the Underground Belgrade Impressions of the foreigners who arrive to Serbia Beach in the Centre of the City 2 Editorial Contents ife in Belgrade is the real challenge for those who have decided to spend part of their THEY SAID ABOUT SERBIA 04 lives in the Serbian capital. Impressions of the foreigners who arrive LReferring to this, one of our collocutors to Serbia through economic and in this magazine issue was the most emotional - Dragan Kapicic, one-time diplomatic channels basketball ace and the actual President of the Basketball Federation of Serbia. ADA CIGANLIJA Belgrade is also the city of secrets since 06 it has become a settlement a couple Beach in the Centre of the City of thousands years ago. Mysteries are being revealed almost every day. INTERVIEW The remains of the Celtic, Roman, 10 Byzantine, and Turkish architectures DRAGAN KAPICIC, are entwined with the modern ones The Basketball Legend that have been shaping Belgrade since the end of the 19th century. Secretive is also the strange world SPIRIT OF THE OLD BELGRADE 12 of underground tunnels, caves and Myths of the Kafana Life shelters that we open to our readers. Many kilometres of such hidden places lie under the central city streets and APARTMENTS 18 parks. They became accessible for visitors only during the recent couple short RENTING of years. 27 Also, Belgrade has characteristic bohemian past that is being preserved HOUSES 28 in the traditions of restaurants and cafes. -

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Ivana Bago 2018 Abstract The dissertation examines the work contemporary artists, curators, and scholars who have, in the last two decades, addressed urgent political and economic questions by revisiting the legacies of the Yugoslav twentieth century: multinationalism, socialist self-management, non- alignment, and -

Zone Na Teritoriji Grada Beograda Četvrtak, 10 Mart 2011 00:00

Zone na teritoriji Grada Beograda četvrtak, 10 mart 2011 00:00 Odlukom o određivanju zona na teritoriji Grada Beograda (Sl. list grada Beograda", br. 60/2009 i 45/2010) određene su zone kao jedan od kriterijuma za utvrđivanje visine lokalnih komunalnih taksi, naknade za korišćenje građevinskog zemljišta i naknade za uređivanje građevinskog zemljišta. Takođe, zone određene tom odlukom primenjuju se i kao kriterijum za utvrđivanje visine zakupnine za poslovni prostor na kome je nosilac prava korišćenja grad Beograd. Na teritoriji grada Beograda postoje devet zona u zavisnosti od tržišne vrednosti objekata i zemljišta, komunalne opremljenosti i opremljenosti javnim objektima, pokrivenosti planskim dokumentima i razvojnim mogućnostima lokacije, kvaliteta povezanosti lokacije sa centralnim delovima grada, nameni objekata i ostalim uslovljenostima. Spisak zona - Prva zona - U okviru prve zone nalaze se: - Zona zaštite zelenila - Područje uže zone zaštite vodoizvorišta za Beograd - Područje uže zone zaštite vodoizvorišta za naselje Obrenovac - Ekstra zona stanovanja - Ekstra zona poslovanja - Druga zona - Treća zona - Četvrta zona - Peta zona - Šesta zona - Sedma zona 1 / 25 Zone na teritoriji Grada Beograda četvrtak, 10 mart 2011 00:00 - Osma zona - Zona specifičnih namena Ovde možete preuzeti grafički prikaz zona u Beogradu. Napomene: 1. U slučaju neslaganja tekstualnog dela i grafičkog priloga, važi grafički prilog . 2. Popis katastarskih parcela i granice katastarskih opština su urađene na osnovu raspoloživih podloga i ortofoto snimaka iz -

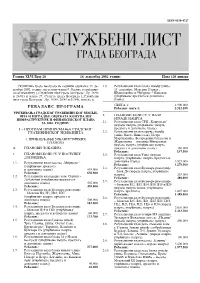

Grada Beograda

ISSN 0350-4727 SLU@BENI LIST GRADA BEOGRADA Godina XLVI Broj 28 16. decembar 2002. godine Cena 120 dinara Skup{tina grada Beograda na sednici odr`anoj 13. de- 1.8. Regulacioni plan bloka izme|u ulica: cembra 2002. godine, na osnovu ~lana 9. Odluke o gra|evin- 14. decembra, Maksima Gorkog, skom zemqi{tu („Slu`beni list grada Beograda”, br. 16/96 [umatova~ke i ^uburske – Kikevac i 26/01) i ~lana 27. Statuta grada Beograda („Slu`beni (utvr|ivawe predloga i dono{ewe list grada Beograda”, br. 18/95, 20/95 i 21/99), donela je plana) –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– SVEGA 1: 1.900.000 REBALANS PROGRAMA Rebalans svega 1: 2.312.100 –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– URE\IVAWA GRADSKOG GRA\EVINSKOG ZEMQI- [TA I IZGRADWE OBJEKATA KOMUNALNE 2. PLANOVI KOJI SU U FAZI INFRASTRUKTURE I FINANSIJSKOG PLANA IZRADE NACRTA ZA 2002. GODINU 2.1. Regulacioni plan SRC „Ko{utwak” (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, á – PROGRAM PRIPREMAWA GRADSKOG predloga i dono{ewe plana) GRA\EVINSKOG ZEMQIŠTA 2.2. Regulacioni plan podru~ja izme|u ulica: Kneza Vi{eslava, Petra 1. PRIBAVQAWE URBANISTI^KIH Martinovi}a, Beogradskih bataqona i PLANOVA @arkova~ke – lokacija Mihajlovac (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, A. PLANOVI LOKACIJA predloga i dono{ewe plana) 160.000 Rebalans: 137.500 1. PLANOVI KOJI SU U POSTUPKU 2.3. Regulacioni plan Umke (izrada DONOŠEWA nacrta, utvr|ivawe nacrta, predloga i 1.1. Regulacioni plan naseqa „Mirijevo” dono{ewe plana) 3.925.000 (utvr|ivawe predloga Rebalans: 3.279.900 2.4. Regulacioni plan Bulevara revolucije i dono{ewe plana) 635.000 – blok D6 (izrada nacrta, utvr|ivawe Rebalans: 656.600 nacrta) 235.000 1.2. -

Lawyers War with Ministry Paralyses Serbian Judiciary

the speech that Serbia’s Prime Min Prime Serbia’s that speech the from quotes the of one Bell but Dolly sought. lawyers the changes substantial the deliver not do provisions the ed that stat Lawyers SerbianChamberof the 30th, October on laws related ries and Nota on Law the to amendments the isworsening. ny image to London audience London to image sells reformist Vučić on Continued A conflict. the to befound urgently resolution must say experts accusations, bitter trade lawyers striking and ministry justice Serbia’s While Serbian judiciary paralyses ministry with war Lawyers “I Dimitar reformer. economic great region’s himself asthe rebrand to wants peacemaker’ Balkan ‘the that confirms LSE the to speech Serbian leader’s The Gordana Gordana COMMENT Although the government adopted adopted government the Although Bechev ANDRIĆ sic Do You Remember Remember DoYou sic clas 1981 Emir Kusturica’s from anecho isnot that No, things.” new learning day, every am changing as ever and the acrimo the and as ever away isasfar on ministry the with adeal strike, on inSerbia went yers law since 50days bout page 3 shiners face face shiners Belgrade’s Belgrade’s last shoe- last +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 oblivion Page 4 - - - - - - and underscoring the fact that the the that fact the underscoring and Parade Pride Gay recent the dled han government the how recalling freedom, media on questions tough off fending confidence, projected er 27 October Monday London School of Economics,LSE, on the at made Vučić, Aleksandar ister, 17 onSeptember onstrike went Serbian lawyers Facing a packed hall, Serbia’s lead hall,Serbia’s apacked Facing Issue No. -

Slu@Beni List Grada Beograda

ISSN 0350-4727 SLU@BENI LIST GRADA BEOGRADA Godina XLVIII Broj 10 26. maj 2004. godine Cena 120 dinara Skup{tina grada Beograda na sednici odr`anoj 25. ma- ma stepenu obaveznosti: (a) nivo 2006. godine za planska ja 2004. godine, na osnovu ~lana 20. Zakona o planirawu i re{ewa za koja postoje argumenti o neophodnosti i opravda- izgradwi („Slu`beni glasnik RS", broj 47/03) i ~l. 11. i nosti sa dru{tvenog, ekonomskog i ekolo{kog stanovi{ta; 27. Statuta grada Beograda („Slu`beni list grada Beogra- (b) nivo 2011. godine za planske ideje za koje je oceweno da da", br. 18/95, 20/95, 21/99, 2/00 i 30/03), donela je postoji mogu}nost otpo~iwawa realizacije uz podr{ku fondova Evropske unije za kandidatske i pristupaju}e ze- REGIONALNI PROSTORNI PLAN mqe, me|u kojima }e biti i Srbija; (v) nivo iza 2011. godine, kao strate{ka planska ideja vodiqa za ona re{ewa kojima ADMINISTRATIVNOG PODRU^JA se dugoro~no usmerava prostorni razvoj i ure|ivawe teri- GRADA BEOGRADA torije grada Beograda, a koja }e biti podr`ana struktur- nim fondovima Evropske unije, ~iji }e ~lan u optimalnom UVODNE NAPOMENE slu~aju tada biti i Republika Srbija. Regionalni prostorni plan administrativnog podru~ja Planska re{ewa predstavqaju obavezu odre|enih insti- grada Beograda (RPP AP Beograda) pripremqen je prema tucija u realizaciji, odnosno okosnicu javnog dobra i javnog Odluci Vlade Republike Srbije od 5. aprila 2002. godine interesa, uz istovremenu punu podr{ku za{titi privatnog („Slu`beni glasnik RS", broj 16/02). -

The Future of Social Housing Is Considered to Be Crucial.” Summary Report

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Committee on Human Settlements ”The future of social housing is considered to be crucial.” summary report Imprint Published by City of Vienna, MA 50 Project Management Wolfgang Förster, Division for Housing Research and International Relations in Housing and Urban Renewal Edited by Europaforum Wien Siegrun Herzog, Johannes Lutter Grafic design clara monti grafik, Vienna Photos Gisela Ortner, Vienna Printed by Leukauf?, Vienna © City of Vienna, 2005 All rights reserved 1 Foreword by Kaj Bärlund, Director, 2 Starting from scratch in Kosovo – the institutional context for new social 52 Environment and Human Settlements Division, UNECE, Geneva housing in Kosovo and the experience of Wales, Malcolm Boorer Foreword by Werner Faymann, City Councillor 3 Responsibilities for housing development at different institutional levels 54 for Housing, Housing Construction and Urban Renewal, Vienna in the Slovak Republic, Alena Kandlbauerova Social housing in Latvia – reality (or current situation) 56 Programme of the Symposium 4 and future perspective, Inara Marana and Valdis Zakis Field Visit 8 “Wohndrehscheibe” – a housing information system for the disadvantaged, 58 Christian Perl Introduction to the summary report 10 Macro-economic framework and social housing finance. Financing systems, 61 Stephen Duckworth Presentations and debates Financing non-profit housing in Switzerland, Ernst Hauri 63 Session 1: The role and evolution of social housing in society 12 Funding for social housing, Jorge Morgado Ferreira -

Plattenbau Bartwigger.Pdf

Voorwoord . 15 Januari 2004, S-bahn S25 richting Wartenberg, Samen met Moskow, St. Petersburg, Leningrad en Berlijn. Op weg naar Marzahn was ik, en al turende Tashkent is Berlijn een van de testgebieden door het grote venster van de S-bahn zag ik ze al in geweest voor de ontwikkeling van de de verte, aan de horizon, opdoemend tegen een geprefabriceerde massawoningbouw, in het Duits grijze hemel: de adembenemende, monotone, genaamd 'Plattenbau'. Middels deze bouwmethode reusachtige betonkolossen. Ik moet het met eigen wisten de leiders van het sociale regime in de vier ogen zien, dacht ik tijdens een college toen ik nog in decennia na WOII hun idealen letterlijk in beton te Berlijn studeerde, waarbij Plattenbausiedlung gieten. In de geschiedenis van de architectuur en de Marzahn de revue passeerde. stedenbouw zijn weinig voorbeelden aan te halen Een dik halfuur vanaf Alexanderplatz, op een waarin politieke, economische en socialistische uitgeleefd S-bahn station, koud, winderig door het idealen zo duidelijk zijn gemanifesteerd als toen. gebrek aan ook maar iets dat op beschutting leek, Alleen al in de voormalig DDR zijn 1,52 miljoen daar stond ik dan, oog in oog…. Waar ik ook keek, woningen gebouwd middels de Plattenbau- Plattenbau. Een gevoel van somberheid daalde op methode. mij neer. Wat heeft de DDR er toe aangezet om dìt Tijdens het socialistische regime functioneerden de te verwezenlijken? Is het er daadwerkelijk zo slecht Platten, zoals ze in de volksmond nog immer wonen als de media en het gros van de worden genoemd, naar behoren en stond men architectuurwereld doen voorkomen? dikwijls in de rij om in aanmerking te komen om zich er te mogen vestigen. -

PROSTOR POSEBNI OTISAK/SEPARAT 82-95 Znanstveni Prilozi Vladan Djokiæ Goran Mickovski

PROSTOR 23 [2015] 1 [49] ZNANSTVENI ÈASOPIS ZA ARHITEKTURU I URBANIZAM A SCHOLARLY JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING SVEUÈILIŠTE POSEBNI OTISAK / SEPARAT OFFPRINT U ZAGREBU, ARHITEKTONSKI FAKULTET Znanstveni prilozi Scientific Papers UNIVERSITY OF ZAGREB, FACULTY 82-95 Goran Mickovski Okružni ured za osiguranje Social Security District Office OF ARCHITECTURE Vladan Djokiæ radnika u Skopju arhitekta in Skopje Designed by the Architect Drage Iblera, 1934. Drago Ibler, 1934 ISSN 1330-0652 CODEN PORREV Izvorni znanstveni èlanak Original Scientific Paper UDK | UDC 71/72 UDK 725.1 D. Ibler (497.7, Skopje)”19” UDC 725.1 D. Ibler (497.7, Skopje)”19” 23 [2015] 1 [49] 1-194 1-6 [2015] Sl. 1. D. Ibler i D. Galiæ: Okružni ured za osiguranje radnika u Skopju, 1934. Fig. 1. D. Ibler and D. Galiæ: Social Security District Office, Skopje, 1934 PROSTOR Znanstveni prilozi | Scientific Papers 23[2015] 1[49] 83 Goran Mickovski, Vladan Djokiæ Univerzitet „Sv. Kiril i Metodij” The Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje Arhitektonski fakultet Skopje Faculty of Architecture Makedonija - 1000 Skopje, Bulevar Partizanski odredi 24 Macedonia - 1000 Skopje, Bulevar Partizanski odredi 24 Univerzitet u Beogradu University of Belgrade Arhitektonski fakultet Faculty of Architecture Srbija - 11000 Beograd, Bulevar kralja Aleksandra 73 Serbia - 11000 Belgrade, Bulevar kralja Aleksandra 73 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Izvorni znanstveni èlanak Original Scientific Paper UDK 725.1 D. Ibler (497.7, Skopje)”19” UDC 725.1 D. Ibler (497.7, Skopje)”19” Tehnièke znanosti / Arhitektura i urbanizam Technical Sciences / Architecture and Urban Planning 2.01.04. -

Mass Heritage of New Belgrade: Housing Laboratory and So Much

PP Periodica Polytechnica Mass Heritage of New Belgrade: Architecture Housing Laboratory and So Much More 48(2), pp. 106-112, 2017 https://doi.org/10.3311/PPar.11621 Creative Commons Attribution b Jelica Jovanović1* research article Received 17 November 2017; accepted 06 December 2017 Abstract 1 Introduction The central zone of New Belgrade has been under tentative It might be difficult for us today to grasp the joy and enthu- protection by the law of the Republic of Serbia; it is slowly siasm of the post-war generation of planners and builders, once gaining the long-awaited canonical status of cultural prop- New Belgrade had started to emerge from the swampy sand erty. However, this good news has often been overshadowed of the left bank of the Sava river. The symbolic burden of the by the desperation among the professionals, the fear among vast marshland, which served as a no-mans-land between the flat owners and the fury among politicians: the first because Ottoman and Habsburg Empire, could not be automatically they grasp the scale of the job-to-be-done, the last because it annulled after the formation of the first Yugoslavia in 1918. interferes with their hopes and wishes, and the second because It took another twenty-something years, a world war and a they are stuck between the first and the third group. This whirl- revolution to get there. However, as well as the political and pool of interests shows many properties of New Belgrade, that economic issues, there was a set of organisational and techno- stretch far beyond the oversimplified narratives of ‘the unbuilt logical obstacles to creating this city. -

The Shrinking of Eastern Germany

JW-12 GERMANY Jill Winder is a Donors’ Fellow of the Institute studying post-reunification Germany through the ICWA work and attitudes of its artists. LETTERS The Shrinking of Eastern Germany By Jill Winder NOVEMBER 25, 2005 Since 1925 the Institute of BERLIN–Cities, in the parlance of modern architectural and urban theory, are al- Current World Affairs (the Crane- most by definition places that expand and grow infinitely. Since the process of Rogers Foundation) has provided industrialization began two centuries ago, people have flocked to urban centers long-term fellowships to enable from the countryside in search of work, better living conditions and access to edu- outstanding young professionals cation. So great is this entrenched concept of cities and growth that recent archi- to live outside the United States tectural and urban-planning theory has almost exclusively focused on the devel- and write about international opment of “mega cities” and the demands of housing exploding populations. Yet areas and issues. An exempt in spite of the rapid pace of urbanization in some areas (notably China), once- operating foundation endowed by thriving cities all over the world suffer from a surprising phenomenon that mod- the late Charles R. Crane, the ern urban planning seems ill suited to deal with: Shrinkage. Institute is also supported by contributions from like-minded Research conducted recently by the United Nations has shown that for every individuals and foundations. two cities that are growing, three are shrinking.1 According to Philipp Oswalt, a Berlin-based architect and director of Schrumpfende Städte (Shrinking Cities), a three- year research project (2002–2005) funded by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (Federal TRUSTEES Cultural Foundation), more than 450 cities worldwide have lost 10 percent of their 2 Bryn Barnard population since 1950; no fewer than 59 of those are in the US.