Canine Recurrent Flank Alopecia: a Synthesis of Theory and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reticulate Hyperpigmentation of the Skin After Topical Application Of

Letters to the Editor 301 Reticulate Hyperpigmentation of the Skin After Topical Application of Benzoyl Peroxide Sir, Our two patients appeared to develop an irritant response on Benzoyl peroxide (BP) is an e¡ective and frequently used topical thetrunk afterapplication of 5% benzoyl peroxide. One medication for the treatment of acne vulgaris. It is a strong, patient applied BP to his face withnoirritation,consistentwith broad spectrum bactericidal agent that signi¢cantly decreases the ¢ndings of Hausteinetal.(3). Both patients then developed the number of Propionibacterium acnes in both the follicle and apattern of reticulate hyperpigmentation after their initial der- on surface skin (1). A common side e¡ect after usage is irritation matitis subsided. Biopsy in both cases was consistent with of the skin, usually manifested as a stinging or burning, and postin£ammatory hyperpigmentation. sometimes accompanied by erythema and scaling. Benzoyl per- Postin£ammatory hyperpigmentation develops after acute oxide is a strong irritant, but a weak allergen, rarely causing a or chronic in£ammation and trauma to the skin. The intensity contact dermatitis (2, 3). Tolerance can be achieved by gradually of the hypermelanosistendstobe more pronounced in darker- increasing the frequency of application over time. We describe skinnedindividuals. Other conditions that produce a pattern of two cases in which topical application of benzoyl peroxide reticulate hyperpigmentation include Riehl's melanosis, resulted in an unusual pattern of reticulate hyperpigmentation which is characterized by reticulate brown-black pigmenta- of the skin, most likely as a sequela of an irritant contact derma- tion of the face and neck. This is thought to be a result of a titis. -

Erythema Ab Igne and Use of Laptop Computers

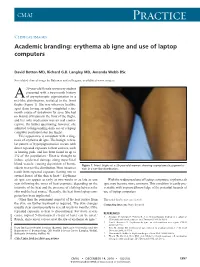

CMAJ Practice Clinical images Academic branding: erythema ab igne and use of laptop computers David Botten MD, Richard G.B. Langley MD, Amanda Webb BSc See related clinical image by Beleznay and colleagues, available at www.cmaj.ca 20-year-old female university student presented with a two-month history A of asymptomatic pigmentation in a net-like distribution, isolated to the front thighs (Figure 1). She was otherwise healthy, apart from having recently completed a six- month course of isotretinoin for acne. She had no history of trauma to the front of the thighs, and her only medication was an oral contra- ceptive. On further questioning, however, she admitted to longstanding daily use of a laptop computer positioned atop her thighs. This appearance is consistent with a diag- nosis of erythema ab igne. The benign, reticu- lar pattern of hyperpigmentation occurs with direct repeated exposure to heat sources, such as heating pads, and has been found in up to 3% of the population.1 Heat is thought to induce epidermal damage along superficial blood vessels, causing deposition of hemo- Figure 1: Front thighs of a 20-year-old woman showing asymptomatic pigmenta- siderin in a net-like distribution. Most instances tion in a net-like distribution. result from repeated exposure (lasting one to several hours) of the skin to heat.2,3 Erythema ab igne can appear as early as two weeks or as late as one With the widespread use of laptop computers, erythema ab year following the onset of heat exposure, depending on the igne may become more common. -

Review Cutaneous Patterns Are Often the Only Clue to a a R T I C L E Complex Underlying Vascular Pathology

pp11 - 46 ABstract Review Cutaneous patterns are often the only clue to a A R T I C L E complex underlying vascular pathology. Reticulate pattern is probably one of the most important DERMATOLOGICAL dermatological signs of venous or arterial pathology involving the cutaneous microvasculature and its MANIFESTATIONS OF VENOUS presence may be the only sign of an important underlying pathology. Vascular malformations such DISEASE. PART II: Reticulate as cutis marmorata congenita telangiectasia, benign forms of livedo reticularis, and sinister conditions eruptions such as Sneddon’s syndrome can all present with a reticulate eruption. The literature dealing with this KUROSH PARSI MBBS, MSc (Med), FACP, FACD subject is confusing and full of inaccuracies. Terms Departments of Dermatology, St. Vincent’s Hospital & such as livedo reticularis, livedo racemosa, cutis Sydney Children’s Hospital, Sydney, Australia marmorata and retiform purpura have all been used to describe the same or entirely different conditions. To our knowledge, there are no published systematic reviews of reticulate eruptions in the medical Introduction literature. he reticulate pattern is probably one of the most This article is the second in a series of papers important dermatological signs that signifies the describing the dermatological manifestations of involvement of the underlying vascular networks venous disease. Given the wide scope of phlebology T and its overlap with many other specialties, this review and the cutaneous vasculature. It is seen in benign forms was divided into multiple instalments. We dedicated of livedo reticularis and in more sinister conditions such this instalment to demystifying the reticulate as Sneddon’s syndrome. There is considerable confusion pattern. -

CSI Dermatology

Meagen M. McCusker, MD [email protected] Integrated Dermatology, Enfield, CT AbbVie - Speaker Case-based scenarios, using look-alike photos, comparing the dermatologic manifestations of systemic disease to dermatologic disease. Select the clinical photo that best matches the clinical vignette. Review the skin findings that help differentiate the two cases. Review etiology/pathogenesis when understood and discuss treatments. Case 1: Scaly Serpiginous Eruption This patient was evaluated for a progressively worsening pruritic rash associated with dyspnea on exertion and 5-kg weight loss. Despite its dramatic appearance, the patient reported no itch. KOH examination is negative (But, who’s good at those anyway?) A. B. Case 1: Scaly Serpiginous Eruption This patient was evaluated for a progressively worsening pruritic rash associated with dyspnea on exertion and 5-kg weight loss. Despite its dramatic appearance, the patient reported no itch. KOH examination is negative (But, who’s good at those anyway?) A. Correct. B. Tinea Corporis Erythema Gyratum Repens Erythema Gyratum Repens Tinea corporis Rare paraneoplastic T. rubrum > T. mentagrophytes phenomenon typically > M. canis associated with lung Risk factors cancer>esophageal and breast Close contact, previous cancers. infection, Less commonly associated with occupational/recreational connective tissue disorders such exposure, contaminated as Lupus or Rheumatoid furniture or clothing, Arthritis gymnasium, locker rooms “Figurate erythema” migrates up 1-3 week incubation → to 1 cm a day centrifugal spread from point of Resolves with treatment of the invasion with central clearing malignancy This patient was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Case 2: Purpuric Eruption on the Legs & Buttocks A 12-year old boy presents with a recent history of upper respiratory tract infection, fever and malaise. -

Importance of a Thorough Physical Examination! Muhammad Imran, M.D., Julian Magadan III, M.D., Mehrdad Maz, M.D

Kansas Journal of Medicine 2015 Physical Examination Importance of a Thorough Physical Examination! Muhammad Imran, M.D., Julian Magadan III, M.D., Mehrdad Maz, M.D. University of Kansas Medical Center Department of Internal Medicine Division of Allergy, Clinical Immunology, & Rheumatology Kansas City, KS A 73-year-old white female presented for management of her tophaceous gout, pyoderma gangrenosum, and chronic back pain. On exam, there was an incidental finding of reticular, reddish-brown, non-tender, macular, non-blanching discoloration on her entire back, with a few superficial erosions (see Figure). The patient did not know the duration of her rash. It was neither pruritic nor painful. She denied arthralgia, fever, chills, or other constitutional symptoms. She did not have a history of insect bites, recent foreign travel, falls, or trauma. She frequently used a heating pad to alleviate her chronic back pain. Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urine analysis, and inflammatory markers were within normal limits. What is most likely diagnosis? A. Vasculitis B. Livedo Reticularis C. Erythema Ab Igne D. Cutaneous Lupus E. Actinic Keratosis 48 Kansas Journal of Medicine 2015 Physical Examination Correct Answer: C. Erythema Ab Igne Erythema ab igne (EAI), also known as ephelis ignealis or toasted skin syndrome, is an unintentional, unperceived, and self-induced condition, which occurs in individuals who persistently use topical or conventional heat to relieve localized pain or cold.1 It is characterized by chronic, localized, erythematous or hyper-pigmented, reticulated, and net-like skin patches in the affected area. It is usually asymptomatic, but burning and pruritus are reported by some patients. -

Dermatological Indications of Disease - Part II This Patient on Dialysis Is Showing: A

“Cutaneous Manifestations of Disease” ACOI - Las Vegas FR Darrow, DO, MACOI Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine This 56 year old man has a history of headaches, jaw claudication and recent onset of blindness in his left eye. Sed rate is 110. He has: A. Ergot poisoning. B. Cholesterol emboli. C. Temporal arteritis. D. Scleroderma. E. Mucormycosis. Varicella associated. GCA complex = Cranial arteritis; Aortic arch syndrome; Fever/wasting syndrome (FUO); Polymyalgia rheumatica. This patient missed his vaccine due at age: A. 45 B. 50 C. 55 D. 60 E. 65 He must see a (an): A. neurologist. B. opthalmologist. C. cardiologist. D. gastroenterologist. E. surgeon. Medscape This 60 y/o male patient would most likely have which of the following as a pathogen? A. Pseudomonas B. Group B streptococcus* C. Listeria D. Pneumococcus E. Staphylococcus epidermidis This skin condition, erysipelas, may rarely lead to septicemia, thrombophlebitis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis. Involves the lymphatics with scarring and chronic lymphedema. *more likely pyogenes/beta hemolytic Streptococcus This patient is susceptible to: A. psoriasis. B. rheumatic fever. C. vasculitis. D. Celiac disease E. membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Also susceptible to PSGN and scarlet fever and reactive arthritis. Culture if MRSA suspected. This patient has antithyroid antibodies. This is: • A. alopecia areata. • B. psoriasis. • C. tinea. • D. lichen planus. • E. syphilis. Search for Hashimoto’s or Addison’s or other B8, Q2, Q3, DRB1, DR3, DR4, DR8 diseases. This patient who works in the electronics industry presents with paresthesias, abdominal pain, fingernail changes, and the below findings. He may well have poisoning from : A. lead. B. -

Erythema Ab Igne: a Rare Presentation of Toasted Skin Syndrome with the Use of a Space Heater

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.13401 Erythema Ab Igne: A Rare Presentation of Toasted Skin Syndrome With the Use of a Space Heater Zarah Haleem 1 , Judith Philip 1 , Safwan Muhammad 2 1. College of Medicine, American University of Antigua, Coolidge, ATG 2. Internal Medicine, University of Maryland Medical Center Midtown Campus, Baltimore, USA Corresponding author: Zarah Haleem, [email protected] Abstract Erythema ab igne, also known as toasted skin syndrome, is an acquired asymmetric hyperpigmented dermatosis that is caused by repeated exposure to moderate heat or infrared radiation. Hyperpigmentation is caused by the degeneration of elastic fibers and basal cells resulting in the release of melanin. Historically found in bakers and industrial workers, this condition has recently resurfaced in medical literature with the use of novel heat sources such as laptops and heated car seats. While this condition can resolve spontaneously after removal of heat exposure, delay in diagnosis and persistent exposure can lead to permanent pigmentation or progression to Merkel cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. Categories: Dermatology, Internal Medicine, Oncology Keywords: erythema ab igne, space heater, toasted skin syndrome, merkel cell carcinoma, cutaneous hyperpigmentation, atypical rash, squamous cell carcinoma Introduction Toasted skin syndrome is a rare hyperpigmented dermatosis that can occur at any site with recurrent exposure to heat or an infrared source. This condition is known to be more prevalent in women than men and patients with chronic pain [1-3]. The pathophysiology does not seem to be fully understood and multiple mechanisms have been proposed, including the repeated heat exposure damaging superficial blood vessels leading to hemosiderin deposition and subsequent hyperpigmentation. -

A Case of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Skin Subsequent to Subcutaneous Foreign Body Mubashir S1, Anwar P2, Hassa I3, Arif T4

Vol. 12, No. 1, 2014 Case Report A Case of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Skin Subsequent to Subcutaneous Foreign Body Mubashir S1, Anwar P2, Hassa I3, Arif T4 1Lecturer, 2Senior Resident, 3Professor and Head, Abstract 4Postgraduate scholar Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin is one of the most Postgraduate Department of Dermatology, STD common non melanoma skin cancers (NMSC), along with basal cell & Leprosy, Govt. Medical College, Srinagar, J & carcinoma (BCC). Besides ultraviolet radiation, the role of exposure K , India. to industrial agents, ionizing radiation and areas of chronic inflammation is associated with the development of SCC. SCC may Address for correspondence also be associated with foreign bodies. We report a rare case of cutaneous SCC in an elderly Kashmiri female, developing subsequent Dr Parvaiz Anwar to subcutaneous non metallic foreign body, which was successfully excised with negative margins, and transposition flap closure. Senior Resident, Postgraduate Department of Dermatology, STD & Leprosy Key words: Squamous cell carcinoma, Foreign body, Transposition Govt. Medical College, Srinagar, J & K, India. flap closure E-mail: [email protected] Citation Mubashir S, Anwar P, Hassa I, Arif T. A case of squamous cell carcinoma of skin subsequent to subcutaneous foreign body. NJDVL 2014; 12(1): 53 - 55. Introduction lesion on left inner thigh. This was preceded, one Squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma are the month back, by a trivial trauma with penetration most important non melanoma skin cancers and of dry piece of broom. Like all Kashmiri exposure to ultraviolet radiation is the most population, she has been in the habit of using important risk factor for the development of these, Kangri for warmth for years together. -

Erythema Ab Igne Following Heating/Cooling Blanket Use in the Intensive Care Unit Robert Paul Dellavalle, MD, Phd, Denver, Colorado Paul Gillum, MD, Denver, Colorado

Erythema Ab Igne Following Heating/Cooling Blanket Use in the Intensive Care Unit Robert Paul Dellavalle, MD, PhD, Denver, Colorado Paul Gillum, MD, Denver, Colorado Erythema ab igne caused by chronic heat expo- pneumonia was subsequently diagnosed and treated sure presents as a net-like hyperpigmentation of with antibiotic therapy. Mechanical ventilation was the skin. We report this condition rapidly evolv- discontinued on hospital day 5, and he was transferred ing due to the inadvertent use or dysfunction of an to step-down care. On hospital day 9, the patient adjustable-temperature blanket in the intensive was discharged home. care unit. The use of heating/cooling blankets, es- In the ICU the patient’s fevers were symptomati- pecially in a patient with altered mental status, can cally treated with acetaminophen and a cooling blan- result in iatrogenic erythema ab igne. ket, the Gaymar Mul-T-Blanket Hyper/Hypothermia Blanket attached to a Blanketrol II heating and cool- rythema ab igne (EAI) is a reticulated hyper- ing source (Cincinnati Subzero Products, Inc.). On pigmented dermatosis typically caused by long- hospital day 3, the patient’s mother noted that the term exposure to heat.1-3 Numerous sources of blanket was being used as a heating pad wrapped E 4,5 heat including peat, coal, gas, and electric fire, steam about her son’s torso. radiators,6 stoves,7 hot-water bottles,3,8,9 infrared One week after discharge, the patient noted a net- lamps,10 heating pads,9 heated reclining chairs,11,12 and like discoloration on his trunk. He presented to der- car heaters13 have produced EAI. -

Generalized Hyperpigmentation After Pyrimethamine Use

Our Dermatology Online Case Report GGeneralizedeneralized hhyperpigmentationyperpigmentation aafterfter ppyrimethamineyrimethamine uusese Ann Sterkens1,2, Vasiliki Siozopoulou1,2, Evelyne Mangodt1,2, Julien Lambert1,2, An Bervoets1,2 1Faculty of Medicine, University of Antwerp, Wilrijk, Belgium, 2Dermatology Department, University Hospital Antwerp, Edegem, Belgium Corresponding author: Dr. Ann Sterkens, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT A 44-year old trans woman of Asian origin presented with generalized hyperpigmentation all over her body for four weeks. Six months before, she presented at the emergency department with motor ataxia and further investigation revealed a new diagnosis of HIV, cerebral toxoplasmosis with cerebral edema and latent syphilis. Two months later she presented with encephalitis: CMV and TBC were diagnosed. At that moment, a lot of new medication was started. Skin biopsy was compatible with a medical eruption. Hyperpigmentation was most probably caused by pyrimethamine, which was given for the treatment of toxoplasmosis. Pyrimethamine was stopped and changed into trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Reevaluation after two months showed fading of the hyperpigmentation, especially in the face, which points towards the right diagnosis. Key words: Generalized hyperpigmentation; Toxoplasmosis; Pyrimethamine; HIV, Trimethoprim; Sulfamethoxazole INTRODUCTION patients. Skin biopsy is not a routine examination but can be done when the clinical diagnosis is not clear. Hyperpigmentation is the darkening of the skin. Most of the time it is caused by an increased melanin CASE REPORT deposition, and in rare cases it is due to deposition of pigments like iron or hemosiderin. Hyperpigmentation A 44-year old transwoman of Asian origin, who can be well circumscribed (lentigines, ephilides, recently came to Belgium, presented with generalized maturational hyperpigmentation, melasma, fixed hyperpigmentation all over the body, also in sun- drug eruption,…) or diffuse. -

Erythema Ab Igne and Malignant Transformation to Squamous Cell Carcinoma

CASE REPORT Erythema Ab Igne and Malignant Transformation to Squamous Cell Carcinoma Elizabeth G. Wilder, MD; Jillian H. Frieder, MD; M. Alan Menter, MD Case Report PRACTICE POINTS A 67-year-old Blackcopy woman presented with a long- • Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a cutaneous reaction standing history of pruritus and “scaly thick bumps” on in response to prolonged exposure to infrared the lower extremities. Upon further questioning, she heat sources at temperatures insufficient to induce reported a 30-year history of placing her feet by an elec- a burn. tric space heater and daily baths in “very hot” water. A • Common infrared heat sources include open fires, reviewnot of systems and medical history were unremark- coal stoves, heating pads, laptop computers, and able, and the patient was not on any medications. Initial electric space heaters. physical examination of the lower extremities demon- • Although considered a chronic pigmentary disorder, strated lichenified plaques and scattered, firm, ulcer- EAI rarely can progress to malignant transforma- ated nodules surrounded by mottled postinflammatory tion, including squamous cell carcinoma. PatientsDo hyperpigmentation with sharp demarcation at the midcalf with EAI should be monitored long-term for malig- bilaterally (Figure 1). nant transformation. A punch biopsy of a representative hyperkeratotic plaque on the right dorsal foot demonstrated full-thick- ness, atypical, keratinizing epithelial cells of the epidermis with moderate nuclear pleomorphism and numerous Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a cutaneous reaction resulting from mitotic figures. The histologic features were consistent prolonged exposure to an infrared heat source at temperatures with a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising in the set- insufficient to cause a burn. -

Dermatologic Conditions in Young Athletes Disclosures Objectives

DermatologyDEPARTMENTNAME DERMATOLOGIC CONDITIONS IN YOUNG ATHLETES Stephanie Jacks, MD Assistant Professor, Dermatology and Pediatrics DEPARTMENTNAME DISCLOSURES I have no conflicts of interest or disclosures. DermatologyDEPARTMENTNAME OBJECTIVES Diagnose common dermatologic conditions seen in young athletes Formulate treatment strategies for skin conditions in young athletes Summarize strategies to prevent the spread of dermatologic conditions among young athletes DermatologyDEPARTMENTNAME OVERVIEW • Skin infections represent 8% of sports-related medical conditions among high school athletes and 20% among college athletes. • Likelihood of contracting a skin infection from an infected opponent is about 33%. From: Likness. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 2011. DermatologyDEPARTMENTNAME ERYTHEMATOUS EROSIONS WITH YELLOW CRUST From: Bolognia et al. Dermatology, 3rd ed. 2012. DermatologyDEPARTMENTNAME IMPETIGO • Usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus • Can be caused by Streptococcus species or a mix • Small pustules or vesicles rupture easily, containing yellow fluid that dries into a “honey-colored crust” • Spreads easily • Hands, towels, clothing • May see fever and lymphadenopathy From: Paller et al. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology, 4th ed. 2011. DermatologyDEPARTMENTNAME IMPETIGO • Reservoir: asymptomatic nasal carriage in 20-40% of adults • Treatment: • Localized, mild: topical antibiotics • mupirocin, bacitracin, polymyxin, gentamicin, erythromycin • More widespread: oral antibiotics • Cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanic