Review Cutaneous Patterns Are Often the Only Clue to a a R T I C L E Complex Underlying Vascular Pathology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiating Between Anxiety, Syncope & Anaphylaxis

Differentiating between anxiety, syncope & anaphylaxis Dr. Réka Gustafson Medical Health Officer Vancouver Coastal Health Introduction Anaphylaxis is a rare but much feared side-effect of vaccination. Most vaccine providers will never see a case of true anaphylaxis due to vaccination, but need to be prepared to diagnose and respond to this medical emergency. Since anaphylaxis is so rare, most of us rely on guidelines to assist us in assessment and response. Due to the highly variable presentation, and absence of clinical trials, guidelines are by necessity often vague and very conservative. Guidelines are no substitute for good clinical judgment. Anaphylaxis Guidelines • “Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening IgE mediated allergic reaction” – How many people die or have died from anaphylaxis after immunization? Can we predict who is likely to die from anaphylaxis? • “Anaphylaxis is one of the rarer events reported in the post-marketing surveillance” – How rare? Will I or my colleagues ever see a case? • “Changes develop over several minutes” – What is “several”? 1, 2, 10, 20 minutes? • “Even when there are mild symptoms initially, there is a potential for progression to a severe and even irreversible outcome” – Do I park my clinical judgment at the door? What do I look for in my clinical assessment? • “Fatalities during anaphylaxis usually result from delayed administration of epinephrine and from severe cardiac and respiratory complications. “ – What is delayed? How much time do I have? What is anaphylaxis? •an acute, potentially -

Reticulate Hyperpigmentation of the Skin After Topical Application Of

Letters to the Editor 301 Reticulate Hyperpigmentation of the Skin After Topical Application of Benzoyl Peroxide Sir, Our two patients appeared to develop an irritant response on Benzoyl peroxide (BP) is an e¡ective and frequently used topical thetrunk afterapplication of 5% benzoyl peroxide. One medication for the treatment of acne vulgaris. It is a strong, patient applied BP to his face withnoirritation,consistentwith broad spectrum bactericidal agent that signi¢cantly decreases the ¢ndings of Hausteinetal.(3). Both patients then developed the number of Propionibacterium acnes in both the follicle and apattern of reticulate hyperpigmentation after their initial der- on surface skin (1). A common side e¡ect after usage is irritation matitis subsided. Biopsy in both cases was consistent with of the skin, usually manifested as a stinging or burning, and postin£ammatory hyperpigmentation. sometimes accompanied by erythema and scaling. Benzoyl per- Postin£ammatory hyperpigmentation develops after acute oxide is a strong irritant, but a weak allergen, rarely causing a or chronic in£ammation and trauma to the skin. The intensity contact dermatitis (2, 3). Tolerance can be achieved by gradually of the hypermelanosistendstobe more pronounced in darker- increasing the frequency of application over time. We describe skinnedindividuals. Other conditions that produce a pattern of two cases in which topical application of benzoyl peroxide reticulate hyperpigmentation include Riehl's melanosis, resulted in an unusual pattern of reticulate hyperpigmentation which is characterized by reticulate brown-black pigmenta- of the skin, most likely as a sequela of an irritant contact derma- tion of the face and neck. This is thought to be a result of a titis. -

Dermatologic Manifestations and Complications of COVID-19

American Journal of Emergency Medicine 38 (2020) 1715–1721 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect American Journal of Emergency Medicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ajem Dermatologic manifestations and complications of COVID-19 Michael Gottlieb, MD a,⁎,BritLong,MDb a Department of Emergency Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, United States of America b Department of Emergency Medicine, Brooke Army Medical Center, United States of America article info abstract Article history: The novel coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. While Received 9 May 2020 much of the focus has been on the cardiac and pulmonary complications, there are several important dermato- Accepted 3 June 2020 logic components that clinicians must be aware of. Available online xxxx Objective: This brief report summarizes the dermatologic manifestations and complications associated with COVID-19 with an emphasis on Emergency Medicine clinicians. Keywords: COVID-19 Discussion: Dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 are increasingly recognized within the literature. The pri- fi SARS-CoV-2 mary etiologies include vasculitis versus direct viral involvement. There are several types of skin ndings de- Coronavirus scribed in association with COVID-19. These include maculopapular rashes, urticaria, vesicles, petechiae, Dermatology purpura, chilblains, livedo racemosa, and distal limb ischemia. While most of these dermatologic findings are Skin self-resolving, they can help increase one's suspicion for COVID-19. Emergency medicine Conclusion: It is important to be aware of the dermatologic manifestations and complications of COVID-19. Knowledge of the components is important to help identify potential COVID-19 patients and properly treat complications. © 2020 Elsevier Inc. -

Dermatological Findings in Common Rheumatologic Diseases in Children

Available online at www.medicinescience.org Medicine Science ORIGINAL RESEARCH International Medical Journal Medicine Science 2019; ( ): Dermatological findings in common rheumatologic diseases in children 1Melike Kibar Ozturk ORCID:0000-0002-5757-8247 1Ilkin Zindanci ORCID:0000-0003-4354-9899 2Betul Sozeri ORCID:0000-0003-0358-6409 1Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Department of Dermatology, Istanbul, Turkey. 2Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Department of Child Rheumatology, Istanbul, Turkey Received 01 November 2018; Accepted 19 November 2018 Available online 21.01.2019 with doi:10.5455/medscience.2018.07.8966 Copyright © 2019 by authors and Medicine Science Publishing Inc. Abstract The aim of this study is to outline the common dermatological findings in pediatric rheumatologic diseases. A total of 45 patients, nineteen with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), eight with Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), six with scleroderma (SSc), seven with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and five with dermatomyositis (DM) were included. Control group for JIA consisted of randomly chosen 19 healthy subjects of the same age and gender. The age, sex, duration of disease, site and type of lesions on skin, nails and scalp and systemic drug use were recorded. χ2 test was used. The most common skin findings in patients with psoriatic JIA were flexural psoriatic lesions, the most common nail findings were periungual desquamation and distal onycholysis, while the most common scalp findings were erythema and scaling. The most common skin finding in patients with oligoarthritis was photosensitivity, while the most common nail finding was periungual erythema, and the most common scalp findings were erythema and scaling. We saw urticarial rash, dermatographism, nail pitting and telogen effluvium in one patient with systemic arthritis; and photosensitivity, livedo reticularis and periungual erythema in another patient with RF-negative polyarthritis. -

Necrotizing Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis Mimicking Necrotizing Fasciitis: a Case Report

International Journal of Research in Orthopaedics Soylemez MS et al. Int J Res Orthop. 2016 Sep;2(3):194-198 http://www.ijoro.org DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/issn.2455-4510.IntJResOrthop20163130 Case Report Necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis mimicking necrotizing fasciitis: a case report Mehmet Salih Soylemez1*, Korhan Ozkan2, Bulent Kılıc3, Samet Erinc2, Irfan Esenkaya2, Bahar Ceyran4 1 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Bingol State Hospital, Bingol, Turkey 2Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 4Department of Pathology, Istanbul Medeniyet University, Goztepe Training and Research Hospital 3Department of Health Sciences, Istanbul Gelisim University, Istanbul, Turkey Received: 19 July 2016 Accepted: 11 August 2016 *Correspondence: Dr. Mehmet Salih Soylemez, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT There are several subtypes of necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which are classified according to their morphological features in biopsy specimens using immunofluorescence microscopy. Necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis is limited to the skin, predominantly that of the lower extremities, and usually spares the palms and soles. The most common skin manifestation is palpable purpura. Other skin manifestations include maculopapular rash, bullae, papules, nodules, ulcers and livedo reticularis. There is no specific laboratory test to determine the diagnosis. There are various diseases presenting with these nonspecific symptoms, and a rapid differential diagnosis must be conducted, because the appropriate differentiation and diagnosis markedly influence the treatment strategy and survival of patients. -

Erythema Ab Igne and Use of Laptop Computers

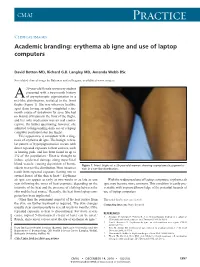

CMAJ Practice Clinical images Academic branding: erythema ab igne and use of laptop computers David Botten MD, Richard G.B. Langley MD, Amanda Webb BSc See related clinical image by Beleznay and colleagues, available at www.cmaj.ca 20-year-old female university student presented with a two-month history A of asymptomatic pigmentation in a net-like distribution, isolated to the front thighs (Figure 1). She was otherwise healthy, apart from having recently completed a six- month course of isotretinoin for acne. She had no history of trauma to the front of the thighs, and her only medication was an oral contra- ceptive. On further questioning, however, she admitted to longstanding daily use of a laptop computer positioned atop her thighs. This appearance is consistent with a diag- nosis of erythema ab igne. The benign, reticu- lar pattern of hyperpigmentation occurs with direct repeated exposure to heat sources, such as heating pads, and has been found in up to 3% of the population.1 Heat is thought to induce epidermal damage along superficial blood vessels, causing deposition of hemo- Figure 1: Front thighs of a 20-year-old woman showing asymptomatic pigmenta- siderin in a net-like distribution. Most instances tion in a net-like distribution. result from repeated exposure (lasting one to several hours) of the skin to heat.2,3 Erythema ab igne can appear as early as two weeks or as late as one With the widespread use of laptop computers, erythema ab year following the onset of heat exposure, depending on the igne may become more common. -

Lesions Resembling Malignant Atrophic Papulosis in a Patient with Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

Lesions Resembling Malignant Atrophic Papulosis in a Patient With Progressive Systemic Sclerosis Clive M. Liu, MD; Ronald M. Harris, MD, MBA; C. David Hansen, MD Malignant atrophic papulosis (MAP), or Degos bleeding, and neurologic deficits. The prognosis is syndrome, is a rare disorder of unknown etiology. usually poor. Histologic characteristics include a It is characterized by a deep subcutaneous vas- vasculopathy below the necrobiotic zone with culopathy resulting in atrophic, porcelain-white endothelial swelling, proliferation, and thrombosis. papules. We report the case of a 42-year-old To our knowledge, only a few cases of MAP associ- woman with a history of progressive systemic ated with connective tissue disease have been sclerosis who presented with painful subcuta- reported: 4 cases with systemic lupus erythematosus, neous nodules on her abdomen along with 1 with dermatomyositis, and 1 with progressive sys- chronic atrophic papules on her upper and lower temic sclerosis.2-5 We present the case report of a limbs. Biopsy results of both types of lesions woman with progressive systemic sclerosis and revealed vascular thrombi without surrounding MAP-like lesions. inflammation. We briefly review the literature on MAP and its association with various connective Case Report tissue diseases. To our knowledge, there have Round erosions with dry central crusts developed on been no previous reports of a patient with the a 42-year-old woman with a long history of progres- clinical and histologic presentations described sive systemic sclerosis, significant pulmonary hyper- here. Although the histologic appearance of the tension, and right heart failure. Although the subcutaneous nodules was very similar to that of lesions were scattered on all limbs, the most promi- the atrophic papules, the clinical characteristics nent lesions extended from the right labium majus of the 2 types of lesions were strikingly different. -

Clinical Manifestations and Management of Livedoid Vasculopathy

Clinical Manifestations and Management of Livedoid Vasculopathy Elyse Julian, BS,* Tania Espinal, MBS,* Jacqueline Thomas, DO, FAOCD,** Nason Rouhizad, MS,* David Thomas, MD, JD, EdD*** *Medical Student, 4th year, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ft. Lauderdale, FL **Assistant Professor, Nova Southeastern University, Department of Dermatology, Ft. Lauderdale, FL ***Professor and Chairman of Surgery, Nova Southeastern University, Ft. Lauderdale, FL Abstract Livedoid vasculopathy (LV) is an extremely rare and distinct hyalinizing vascular disease affecting only one in 100,000 individuals per year.1,2 Formerly described by Feldaker in 1955 as livedo reticularis with summer ulcerations, LV is a unique non-inflammatory condition that manifests with thrombi formation and painful ulceration of the lower extremities.3 Clinically, the disease often displays a triad of livedo racemosa, slow-healing ulcerations, and atrophie blanche scarring.4 Although still not fully understood, the primary pathogenic mechanism is related to intraluminal thrombosis of the dermal microvessels causing occlusion and tissue hypoxia.4 We review a case in which the patient had LV undiagnosed and therefore inappropriately treated for more than 20 years. To reduce the current average five-year period from presentation to diagnosis, and to improve management options, we review the typical presentation, pathogenesis, histology, and treatment of LV.4 Upon physical exam, the patient was found to have the patient finally consented to biopsy. The ACase 62-year-old Report Caucasian male presented in an a wound on the right medial malleolus measuring pathology report identified ulceration with fibrin assisted living facility setting with chronic, right- 6.4 cm x 4.0 cm x 0.7 cm with moderate serous in vessel walls associated with stasis dermatitis lower-extremity ulcers present for more than 20 exudate, approximately 30% yellow necrosis characterized by thick-walled capillaries and years. -

Skin Manifestations of Illicit Drug Use Manifestações Cutâneas

RevABDV81N4.qxd 12.08.06 13:10 Page 307 307 Educação Médica Continuada Manifestações cutâneas decorrentes do uso de drogas ilícitas Skin manifestations of illicit drug use Bernardo Gontijo 1 Flávia Vasques Bittencourt 2 Lívia Flávia Sebe Lourenço 3 Resumo: O uso e abuso de drogas ilícitas é um problema significativo e de abrangência mun- dial. A Organização das Nações Unidas estima que 5% da população mundial entre os 15 e 64 anos fazem uso de drogas pelo menos uma vez por ano (prevalência anual), sendo que meta- de destes usam regularmente, isto é, pelo menos uma vez por mês. Muitos dos eventos adver- sos das drogas ilícitas surgem na pele, o que torna fundamental que o dermatologista esteja familiarizado com essas alterações. Palavras-chave: Drogas ilícitas; Drogas ilícitas/história; Drogas ilícitas/efeitos adversos; Pele; Revisão Abstract: Illicit drug use and abuse is a major problem all over the world. The United Nations estimates that 5% of world population (aged 15-64 years) use illicit drugs at least once a year (annual prevalence) and half of them use drugs regularly, that is, at least once a month. Many adverse events of illicit drugs arise on the skin and therefore dermatologists should be aware of these changes. Keywords: Street drugs; Street drugs/history; Street drugs/adverse effects; Skin; Review HISTÓRICO Há mais de cinco mil anos na Mesopotâmia, minorar o sofrimento dos condenados. região onde hoje se situa o Iraque, os poderes cal- Provavelmente seja o ópio a droga nephente à qual mantes, soníferos e anestésicos do ópio (do latim Homero se referia como “o mais poderoso destrui- opium, através do grego opion, ‘seiva, suco’) já eram dor de mágoas”.1,2 conhecidos pelos sumérios. -

Lessons from Dermatology About Inflammatory Responses in Covid‐19

Received: 2 May 2020 Revised: 14 May 2020 Accepted: 15 May 2020 DOI: 10.1002/rmv.2130 REVIEW Lessons from dermatology about inflammatory responses in Covid-19 Paulo Ricardo Criado1,2 | Carla Pagliari3 | Francisca Regina Oliveira Carneiro4 | Juarez Antonio Simões Quaresma4 1Dermatology Department, Centro Universitário Saúde ABC, Santo André, Brazil 2Dermatology Department, Faculdade de Medicina, Centro Universitário Saúde ABC, Santo André, Brazil 3Pathology Department, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de S~ao Paulo, S~ao Paulo, Brazil 4Center of Biological and Health Sciences, State University of Pará, Belém, Brazil Correspondence Professor Paulo Ricardo Criado MD, PhD, Summary Dermatology Department, Centro The SARS-Cov-2 is a single-stranded RNA virus composed of 16 non-structural pro- Universitário Saúde ABC, Rua Carneiro Leao~ 33 Vila Scarpelli, Santo André, SP 09050-430, teins (NSP 1-16) with specific roles in the replication of coronaviruses. NSP3 has the Brazil. property to block host innate immune response and to promote cytokine expression. Email: [email protected] NSP5 can inhibit interferon (IFN) signalling and NSP16 prevents MAD5 recognition, depressing the innate immunity. Dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages are the first cell lineage against viruses' infections. The IFN type I is the danger signal for the human body during this clinical setting. Protective immune responses to viral infec- tion are initiated by innate immune sensors that survey extracellular and intracellular space for foreign nucleic acids. In Covid-19 the pathogenesis is not yet fully under- stood, but viral and host factors seem to play a key role. Important points in severe Covid-19 are characterized by an upregulated innate immune response, hypercoagulopathy state, pulmonary tissue damage, neurological and/or gastrointes- tinal tract involvement, and fatal outcome in severe cases of macrophage activation syndrome, which produce a ‘cytokine storm’. -

Presented: February 2, 2017 Thru February 4, 2017

2017 ACP Colorado Chapter Meeting February 2, 2017 thru February 4,2017 Broadmoor Hotel, Colorado Springs, Colorado Resident Abstracts Presented: February 2, 2017 thru February 4, 2017 2017 ACP Colorado Chapter Meeting – February 2, 2017 thru February 4, 2017 – Broadmoor Hotel – Colorado Springs, Colorado Name: Angela Burgin, MD Presentation Type: Oral Presentation Residency Program: University of Colorado School of Medicine Additional Authors: Winthrop Lockwood MS3, Katarzyna Mastalerz, MD Abstract Title: Use Clean Needles, Boil you Cotton: Advice for the Modern Drug User Abstract Information: Introduction: Fever in an intravenous drug abuser results in a wide differential diagnosis for the physician to consider, ranging from simple soft tissue infections to endocarditis or epidural abscess. This large breadth of possibilities often leads to dilemmas on which studies to order first, usually resulting in an expensive evaluation. We present one more option to add to the differential diagnosis in an IV drug user who presents with fever, with the hopes of increasing awareness of this condition to the medical community. Case Description: A 31 year old female with a history significant for IV drug abuse presented with dyspnea, chest pain, severe abdominal pain, right arm swelling, and generalized weakness for several days. She worked for a home health company and admitted to recently injecting hydromorphone and other opiates into her veins. Physical exam on admission was notable for a high fever, tachycardia, and right forearm edema, erythema, and induration, with a benign chest and abdominal exam. Ancillary studies revealed a urine toxicology positive for opiates, methadone, and cocaine, as well as a white blood cell count of 13. -

Degos-Like Lesions Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Degos-Like Lesions Associated with SLE pISSN 1013-9087ㆍeISSN 2005-3894 Ann Dermatol Vol. 29, No. 2, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2017.29.2.215 CASE REPORT Degos-Like Lesions Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Min Soo Jang, Jong Bin Park, Myeong Hyeon Yang, Ji Yun Jang, Joon Hee Kim, Kang Hoon Lee, Geun Tae Kim1, Hyun Hwangbo, Kee Suck Suh Departments of Dermatology and 1Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea Degos disease, also referred to as malignant atrophic pap- 29(2) 215∼218, 2017) ulosis, was first described in 1941 by Köhlmeier and was in- dependently described by Degos in 1942. Degos disease is -Keywords- characterized by diffuse, papular skin eruptions with porce- Degos disease, Degos-like lesions, Systemic lupus eryth- lain-white centers and slightly raised erythematous te- ematosus langiectatic rims associated with bowel infarction. Although the etiology of Degos disease is unknown, autoimmune dis- eases, coagulation disorders, and vasculitis have all been INTRODUCTION considered as underlying pathogenic mechanisms. Approx- imately 15% of Degos disease have a benign course limited Degos disease is a rare systemic vaso-occlusive disorder. to the skin and no history of gastrointestinal or central nerv- Degos-like lesions associated with systemic lupus eryth- ous system (CNS) involvement. A 29-year-old female with ematosus (SLE) are a type of vasculopathy. Almost all history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with Degos-like lesions have the clinical pathognomonic ap- a 2-year history of asymptomatic lesions on the dorsum of all pearance of porcelain-white, atrophic papules with pe- fingers and both knees.