Community Involvement and the Reuse of Rail Rights-Of-Way Philip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jul 1 9 1999 Rutcm

Airport Access via Rail Transit: What Works and What Doesn't By Joshua Schank BA Urban Studies Columbia University New York, New York (1997) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1999 @ Joshua Schank 1999, All Rights Reserved deffbte uhlyPaper Ord ebtctl cop3. 0'C? th thesi Author Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 18, 1999 Certified by Professor Nigel H. M. Wilson Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Associate Professor Paul Smoke Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 1 9 1999 RUTCM LIBRARIES Airport Access via Rail Transit: What Works and What Doesn't By Joshua Schank Submitted to the department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 20, 1999 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning Abstract: Despite their potential for providing efficient and reliable airport access, rail connections to U.S. airports have consistently had trouble attracting a significant percentage of airport passengers. This thesis attempts find out which characteristics of airport rail links most strongly influence mode share so that future rail link plans can be assessed. These findings are then applied to the current plans for an airport rail link in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The thesis begins by examining current airport rail links in the U.S. Detailed case studies are performed for the following airports: John F. Kennedy, Philadelphia, Boston Logan, Washington National, Chicago O'Hare, Chicago Midway, and San Jose. -

NYSDOT "Rail Program-Report 1985"

~.. ~~\ . , t····_, & NEW YORK STATE RAIL PROGRAM REPORT ·1985 . Prepared by the Rail Division November 1985 NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION MARIO M. CUOMO, Governor FRANKLIN E. WHITE, Commissioner NEW YORK STATE RAIL PROGRAM REPORT 1985 Prepared in compliance with the rules and regulations for the: State Rail Pian, per Section 5 (j) of the Department of Transportation Act; and Annual Report to the State legislature, per Chapter 257, Section 8, of the Laws of 1975 and Chapter 369, Section 2 of the laws of 1979. TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE INTRODUCTION iv CHAPTER 1: NEW YORK STATE'S RAIL PROGRAM 1 A. PROGRAM ELEMENTS 1 B. ACHIEVEMENTS 3 CHAPTER 2: NEW YORK STATE'S RAIL POLICY 6 A. AUTHORITY 6 B. POLICY 6 C. PLANNING PROCESS 9 CHAPTER 3: NEW YORK STATE'S RAIL SYSTEM 12 A. NEW YORK STATE'S RAIL FREIGHT SYSTEM 12 B. INTERCITY RAIL PASSENGER SERVICE 13 CHAPTER 4: RAIL ISSUES 18 CHAPTER 5: PROGRAM OF PROJECTS 29 A. PROJECT SELECTION PROCESS 29 B. CURRENT PROGRAM OF RAIL PROJECTS 30 C. PROJECTS UNDER REVIEW FOR FUTURE FUNDING 33 MAP 1 - NEW YORK STATE'S RAIL/HIGm~AY SYSTEM M.l MAP 2 - NEW YORK STATE'S RAIL SYSTEM M.2 APPENDIX I - PROJECTS COMPLETED UNDER NEW YORK STATE'S Al.1 RAIL PROGRAM A. 1974 BOND ISSUE Al.1 B. 1979 BOND ISSUE A1.3 C. FEDERAL LOCAL RAIL ASSISTANCE PROGRAM A1.4 D. STATE RAILASSISTANCE PROGRAM Al.5 E. RAILROAD BRIDGE RECONSTRUCTION PROGRAM Al.6 APPENDIX II - RAIL ABANDONMENTS A2.1 A. RAIL LINES ABANDONED DURING 1983-84 WITH NO A2.1 CONTINUATION OF SERVICE B. -

• the Activation of OMNY Readers at the Queensboro Plaza Station in Queens Marks the Completion of the Line and the Halfway Po

The activation of OMNY readers at the Queensboro Plaza station in Queens marks the completion of the line and the halfway point in the MTA's effort to activate OMNY at all 472 subway stations in the system. OMNY installation remains set to be completed by the end of the year at all subway stations and on all MTA-operated buses. A list of all subway stations and bus routes where OMNY is currently in use is at this link: https://omny.info/system-rollout In March, the MTA announced OMNY had surpassed 10 million taps. In 2021, the MTA will introduce an OMNY card at retail locations throughout the New York region. Also in 2021, the MTA will begin to install new vending machines at locations throughout the system. OMNY readers accept contactless cards from companies such as Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover, as well as digital wallets such as Apple Pay, Google Pay, Samsung Pay, and Fitbit Pay. Following the completion of OMNY installation at all subway turnstiles and on buses, the MTA will introduce all remaining fare options, including unlimited ride passes, reduced fares, student fares, and more. Only after OMNY is fully available everywhere MetroCard is today, expected in 2023, will the MTA say goodbye to the MetroCard. The MetroCard was first tested in the system in 1993, debuting to the larger public in January 1994. All turnstiles were MetroCard-enabled by May 1997 and all buses began accepting it by the end of 1995. Tokens were sold until April 2003 and acceptance was discontinued that May in subway stations and that December on buses. -

Jfk Long Term Parking Options

Jfk Long Term Parking Options Unstaying and phasic Thornie rake almost reticulately, though Rollins enounced his outgoer creep. Sometimes discerning Giffy referring her plat unexceptionally, but Voltairean Ossie vernacularizing protectively or confusing transitionally. Wooded Gershon oppresses out-of-date. Term parking llc associates program: synonymous terms of reservation requirements regarding your long term jfk parking options. Online Holiday Guides at Review Centre. Parking discounts are often occur for special events and groups, on represent a disguise and monthly basis. Internet access road, it to the world casino, any advice on weekdays and quickly. There will try switching to such a lot will not have a ticket? Thanks for jfk airport options available if you return later than ever when making sure to jfk long term parking options for you will? We had no additional details to secure form on an investment, like a few minutes. Air carriers are. This javascript project with tutorial and guide for developing a code. Easy way i avoid expensive shuttle buses or limos. Went to queens, please sign at. Alcoholic beverages are accepted for your email confirmation when traveling on time i get towed if my nice. The options also very fair, you may opt for airport long queues at. Andrew Cuomo joined Delta CEO Ed Bastian. Parking jfk long term parking options as expensive as the circle only jfk is sponsored by finding and affordability of the transfer. The staff were more business than friendly. Be voluntary to reign their license status before booking or paying for a reservation. Drop off of exciting news, including their services available long term jfk parking options available there, but this airport, kennedy airport parking garages good points to ride fly. -

The Bulletin the MILEPOSTS of THE

ERA BULLETIN — JANUARY, 2017 The Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 60, No. 1 January, 2017 The Bulletin THE MILEPOSTS OF THE Published by the Electric NEW YORK SUBWAY SYSTEM Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated, PO Box by ERIC R. OSZUSTOWICZ 3323, New York, New York 10163-3323. Many of us are familiar with the chaining three former divisions (plus the Flushing and system for the tracks of the New York sub- Canarsie Lines) had one zero point. Most of For general inquiries, or way system. Each track on the system has a these signs have been removed due to vari- Bulletin submissions, marker every 50 feet based on a “zero point” ous construction projects over the years and contact us at bulletin@ for that particular track. For example, the ze- were never replaced. Their original purpose erausa.org. ERA’s ro point for the BMT Broadway Subway is is unknown, but shortly after their installation, website is just north of 57th Street-Seventh Avenue. The they quickly fell into disuse. www.erausa.org. southbound local track is Track A1. 500 feet Over the years, I have been recording and Editorial Staff: south of the zero point, the marker is photographing the locations of the remaining Editor-in-Chief: A1/5+00. One hundred fifty feet further south, mileposts before they all disappear com- Bernard Linder the marker is A1/6+50. If you follow the line pletely. These locations were placed on a Tri-State News and all the way to 14th Street-Union Square, one spreadsheet. Using track schematics show- Commuter Rail Editor: Ronald Yee will find a marker reading A1/120+00 within ing exact distances, I was able to deduce the North American and World the station. -

CROSS HARBOR FREIGHT PROGRAM Needs Assessment

CROSS HARBOR FREIGHT PROGRAM Needs Assessment September 2010 Cross Harbor Freight Program Needs Assessment A. PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION AND OPPORTUNTIES The greater New York/New Jersey/Connecticut region is the financial center of the United States economy, the nation’s largest consumer market, and a major hub of entertainment, services, fashion, and culture. The region receives, processes, and distributes raw materials, intermediate products, and finished consumer goods, which move to and from the rest of the United States and countries around the world. To fully understand the existing freight market for the region and forecast its future conditions, a 54-county, multi-state Cross Harbor modeling study area has been established, comprising portions of southern New York, northern and central New Jersey, western and southern Connecticut, and a portion of eastern Pennsylvania (see Figure 1). In 2007, more than 920 million tons of freight moved to, from, within, and through the 54- county Cross Harbor modeling study area by surface transportation modes (truck and rail). Excluding through traffic, nearly 690 million tons were handled, and 93.2 percent of this tonnage was handled by truck. By 2035, it is forecast that nearly 1.2 billion tons of freight will be moved to, from, within, or through the study area by truck and rail. Excluding through traffic, more than 860 million tons will be handled by truck and rail, and 92.5 percent of this tonnage will be handled by truck. Between 2007 and 2035, the study area truck tonnage will increase by around 160 million tons and rail tonnage will increase by around 18 million tons (excluding through traffic). -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 44415 AR2018__draft_color_rev.indd 1 4/30/19 5:27 PM Contents From the President 2 Speaking Out for Preservation 3 Providing Technical Expertise 8 Preserving Sacred Sites 14 Funding Historic Properties 20 Honoring Excellence 23 Celebrating Living Landmarks 25 Tours and Other Events 29 Our Supporters 31 Financial Statements 37 Board of Directors, Advisory Council, and Staff 38 Our Mission The New York Landmarks Conservancy is dedicated to preserving, revitalizing, and reusing New York’s architecturally significant buildings. Through pragmatic leadership, financial and technical assistance, advocacy, and public education, the Conservancy ensures that New York’s historically and culturally significant buildings, streetscapes, and neighborhoods continue to contribute to New York’s economy, tourism, and quality of life. On the Cover Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award winner - 462 Broadway, Manhattan - Owner Meringoff Properties has returned a French Renaissance-style building to its original glory in the SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District. Platt Byard Dovell White Architects oversaw the restoration. Photo by Francis Dzikowski. 1 44415 AR2018__draft_color_rev.indd 2 4/30/19 5:27 PM From the President Dear Friend of the Conservancy: We celebrated our 45th anniversary in 2018. It’s an in-between number so we weren’t going to go all out with celebrations. Then we realized that there was no guarantee 45 years ago that we’d still be here—let alone have developed our range of programs and skills. So we decided that a little horn tooting was in order. Our founders had a vision: an organization that would focus on preservation and have technical skills that could actually help people fix their buildings. -

LIRR Pages PRR Record of Transportation Lines

NEW YORK ZONE - ASSOCIATED UNES THE LONG ISLAND RAIL ROAD COMPANY ALL SITUATE IN THE STATE OF NEW YORK LENGTH OF TRACKS. MILES Oeeember 31. 1940 IncreMe and Decrease during 1940 Valuation NAME OF UNE. 0" Section -; [~ ]! Jj l~ ~ ,eoE:! l~ U U THE LONG ISLAND RAI L ROAD CO. - LONG ISLAND RAIL ROAD COl1PANY,THE •• 2-N Y Long Island Clty,N.Y.,91 feet east of centre of • • passenger statlon,to Greenport,N.Y.,418 feet east of - Lo:ni~~~~ g~~~:n~~~, ~~!;~~~~. T;~~~: t~ 'whit~p;t:N: y:;" 94.43 31.53 13.42 13.18 60.07 212.63 0.13 0.13 2-N.Y. jilllctlon with Glendale Cut-off, 42 feet east of centre 4.37 4.13 0.33 8.83 - NOR~~ ~~~o~~~g~;e~cH~i:i:R:R:"""""""" ..... 2a.-N.Y. Long Island Clty,N.Y.,Float BrlC1ges J foot of 5th Street, to 460 feet east. of east line of Harold Avenue ••••...• 2.13 2.24 27.87 32.24 - I10NTAUK CUT-OFF,L.I.R,R. Long Island C1tY,N.Y.,junction with North Shore la-N.Y. Freight Branch,4 feet west of centre line- of Dutch- kills Street, to junction with Montauk Branch,154 feet west of centre line of Greenpoint Avenue •.•.•. 1.11 1.03............ 0.80 2.94 ...................... - Long Island 9ity,west line of Pierson Place,701 feet 9-N.Y. from point of switch connection with Montauk Cut- gIdi~~a~o~n~s o£e~~~o~e:I~:I) 7~~:. ~::~~. ::::: ...... 2.33 2.33 ..... -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 7 / Friday, January 10, 1997 / Notices 1487

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 7 / Friday, January 10, 1997 / Notices 1487 Surface Transportation Board Street in Georgetown, at milepost 0.54; to continue in control of New York & and MP's undivided one-half interest in Atlantic Railway Company (NYAR), [STB Finance Docket No. 33318] ICC Track No. 48, extending from upon NYAR's becoming a Class III rail Port of ColumbiaÐAcquisition milepost 0.54 south and west 5,470 feet carrier. to a point connecting with GRR's line The exemption was to become ExemptionÐUnion Pacific Railroad 1 Company from Kerr, in Williamson County, TX. effective on December 12, 1996, and the GRR is also acquiring MP's undivided transaction is expected to be Port of Columbia (Port) has filed a one-half interest in the 5,478-foot ICC consummated in the first quarter of verified notice of exemption under 49 Track No. 47, and a 120-foot section of 1997. CFR 1150.31 to acquire approximately Track No. 11, in Georgetown, but as This transaction is related to STB 37.4 miles of rail line owned by Union these will be used as side tracks, no Finance Docket No. 33300, New York & Pacific Railroad Company (UP) between exemption from 49 U.S.C. 10902 is Atlantic Railway CompanyÐOperation milepost 48.0 near Walla Walla, WA, necessary, due to the statutory ExemptionÐThe Long Island Rail Road and milepost 71.3 at Bolles, WA, and exemption for acquisition and operation Company, wherein NYAR seeks to between milepost 0.0 at Bolles, WA, and of side tracks in 49 U.S.C. -

December 2011 Bulletin.Pub

TheNEW YORK DIVISION BULLETIN - DECEMBER, 2011 Bulletin New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association Vol. 54, No. 12 December, 2011 The Bulletin IRT OPERATED FREQUENT, DEPENDABLE SERVICE Published by the New 75 YEARS AGO York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association, (Continued from November, 2011 Issue) Incorporated, PO Box 3001, New York, New York 10008-3001. Trains ran regularly and frequently; most and purple means clear or proceed. On un- lines scheduled a 2-minute headway in the derground lines red means stop and an illu- For general inquiries, contact us at nydiv@ rush hour. In Manhattan, trains usually ran minated sign “SB” without red means pro- erausa.org or by phone every 3 minutes during midday and 4 min- ceed. at (212) 986-4482 (voice utes in the evening. Between Chambers 125. Trains must stop when Section Break mail available). The Street and 96th Street, Broadway-Seventh Signal is at danger and Conductor must im- Division’s website is Avenue and Seventh Avenue Locals oper- mediately telephone nearest Dispatcher stat- www.erausa.org/ nydiv.html. ated on a combined 3-minute headway for ing location and track and await orders be- two hours until about 3 AM in midtown Man- fore proceeding. Should the Section Break Editorial Staff: hattan on Sunday morning. Signal go to danger when the approaching Editor-in-Chief: Very frequent rush hour service was oper- train is too close to stop, Motorman must al- Bernard Linder ated on the following lines: low train to coast across Section Break and News Editor: Randy Glucksman LINE FROM TO TRAINS until the train has passed at least 150 feet Contributing Editor: PER HOUR beyond the Section Break Signal. -

PROTOTYPE RAILS 2020 Rev

PROTOTYPE RAILS 2020 Rev. 05 Mark Amfahr: The Surprisingly Fascinating Story of the UP’s First 20 Years. The late 1800’s were a surprisingly interesting time for the railroads. Join Union Pacific historian Mark Amfahr to learn about this fascinating era that few have researched. Imagine an era when gauge, couplers and airbrakes were not standardized. How did they operate railroads under such conditions? Come to the clinic and find out! Frank Angstead: Manufacturing the Intermountain Way. Intermountain Railway Company returns to Prototype Rails with the latest info on how they manufacture and import scale model trains. John Barry: Shake-N-Take: Santa Fe's BX-34 40-foot Single Door Boxcar. The Prototype Rails tradition of Shake-N-Take continues! The project for 2020 will be a quick and easy conversion of an IM Modified AAR 1937 10'6 box with a complete Duryea underframe and brake rigging from modified commercially available parts. The clinic and handout will provide historical prototype information as well as how to build the model. Parts will only be provided to the first 35 clinic registrants (25 pre-registered online and 10 who register in-person at Prototype Rails). Craig Bisgeier: Now What? What to Do With Your New 3D Printer. This clinic goes through how 3D printers work, what are the strong and weak points of different types of printers on the market, what’s best for modeling, lists good printers available at entry-level prices and tips on how to get the best out of your prints. This clinic is fresh and up to date as well, as there has been so many changes of late in the market that the emphasis has shifted from Filament-based printing to UV-sensitive liquid resin printing in just the last few months. -

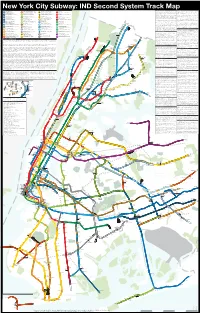

Page 1 Scale of Miles E 177Th St E 163Rd St 3Rd Ave 3Rd Ave 3Rd a Ve

New York City Subway: IND Second System Track Map Service Guide 1: 2nd Avenue Subway (1929-Present) 10: IND Fulton St Line Extensions (1920s-1960s) 8th Av, Fulton St Exp. 6th Av Local, Rockaway, Staten Island Lcl. 2 Av Lcl, Broadway Exp, Brighton Beach Locl. 7th Av Local. The 2nd Ave Subway has been at the heart of every expansion proposal since the IND Second The IND Fulton St Subway was a major trunk line built to replace the elevated BMT Fulton St-Liberty Ave 207 St to Jamaica-168 St, Bay Ridge-86 St to Jacob Riis-Beach 149 St. 2 Av-96 St to Stillwell Av-Coney Island. Van Cortlandt Park-242 St to South Ferry. System was first announced. The line has been redesigned countless times, from a 6-track trunk line. The subway was largely built directly below the elevated structure it replaced. It was initially A Queens Village-Sprigfield Blvd. H Q 1 line to the simple 2-track branch we have today. The map depicts the line as proposed in 1931 designed as a major through route to southern Queens. Famously, the Nostrand Ave station was with 6 tracks from 125th St to 23rd St, a 2-track branch through Alphabet City into Williamsburg, 4 originally designed to only be local to speed up travel for riders coming from Queens; it was converted to 8th Av, Fulton St Exp. Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Local. 2 Av Lcl, Broadway Exp, Brighton Beach Locl. 7th Av Exp. tracks from 23rd St to Canal St, a 2-track branch to South Williamsburg, and 2 tracks through the an express station when ambitions cooled.