Khyber Agency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgroun Dj (IN BLOCK LETTERS) 2

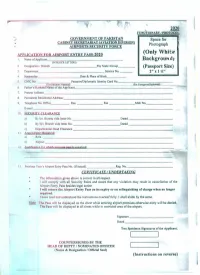

ps 2020 FUNCfIONARY / PROTOCOL GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN Space for CABINET SECRETARIAT (AVIATION DIVISION) Photograph AIRPORTS SECURITY FORCE (Only White APPLICATION FOR AIRPORT ENTRY PASS-2020 I. Name of Applicant._---.,..--,..--:-=:-:-::==-=::-- _ Backgroun dJ (IN BLOCK LETTERS) 2. Designation I Branch Pay Scale IGroup _ (Passport Size) 3. Department Service No. _ 2" x 1 ~" 4. Nationality Date & Place of Birth _ 5. CNIC No. Passport/Diplomatic Identity Card No. _:__-----:--,------ (For Pakistani National) "" _ (For Foreigners/Diploma 6. Father's/Husband Name of the Applicant, _ 7. Present Address _ 8, Permanent Residential Address: --, _ 9. Telephone No. Office Res. Fax Mob No. _ E-mail _ 10. SECURITY CLEARANCE a) By Int. Bureau vide letter No. Dated _ b) By Spl. Branch vide letter No. Dated _ c) Departmental Head Clearance _ I I. Area/Airport Required a) Area _ b) Ai~ort _ 12. Justification for which purpose pass is required. 13. Previous Year's Airport Entry Pass No. (if issued). Reg. No. _ CERTIFICATE / UNDERTAKING • The information given above is correct in all respect. • I will comply with all Security Rules and aware that any violation may result in cancellation of the Airport Entry Pass besides legal action. • I will return the Airport Entry Pass on its expiry or on relinquishing of charge when no longer required. • I have read and understood the instructions overleaf fully. I shall abide by the same. Note The Pass will be displayed on the chest while entering airport premises otherwise entry will be denied. The Pass will be displayed at all times while in restricted area of the airport. -

Resettlement Policy Framework

Khyber Pass Economic Corridor (KPEC) Project (Component II- Economic Corridor Development) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Resettlement Policy Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Peshawar Public Disclosure Authorized March 2020 RPF for Khyber Pass Economic Corridor Project (Component II) List of Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank AH Affected household AI Access to Information APA Assistant Political Agent ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan BHU Basic Health Unit BIZ Bara Industrial Zone C&W Communication and Works (Department) CAREC Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation CAS Compulsory acquisition surcharge CBN Cost of Basic Needs CBO Community based organization CETP Combined Effluent Treatment Plant CoI Corridor of Influence CPEC China Pakistan Economic Corridor CR Complaint register DPD Deputy Project Director EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Environmental Protection Agency ERRP Emergency Road Recovery Project ERRRP Emergency Rural Road Recovery Project ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FBR Federal Bureau of Revenue FCR Frontier Crimes Regulations FDA FATA Development Authority FIDIC International Federation of Consulting Engineers FUCP FATA Urban Centers Project FR Frontier Region GeoLoMaP Geo-Referenced Local Master Plan GoKP Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa GM General Manager GoP Government of Pakistan GRC Grievances Redressal Committee GRM Grievances Redressal Mechanism IDP Internally displaced people IMA Independent Monitoring Agency -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

Dr Javed Iqbal Introduction IPRI Journal XI, No. 1 (Winter 2011): 77-95

An Overview of BritishIPRI JournalAdministrativeXI, no. Set-up 1 (Winter and Strategy 2011): 77-95 77 AN OVERVIEW OF BRITISH ADMINISTRATIVE SET-UP AND STRATEGY IN THE KHYBER 1849-1947 ∗ Dr Javed Iqbal Abstract British rule in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, particularly its effective control and administration in the tribal belt along the Pak-Afghan border, is a fascinating story of administrative genius and pragmatism of some of the finest British officers of the time. The unruly land that could not be conquered or permanently subjugated by warriors and conquerors like Alexander, Changez Khan and Nadir Shah, these men from Europe controlled and administered with unmatched efficiency. An overview of the British administrative set-up and strategy in Khyber Agency during the years 1849-1947 would help in assessing British strengths and weaknesses and give greater insight into their political and military strategy. The study of the colonial system in the tribal belt would be helpful for administrators and policy makers in Pakistan in making governance of the tribal areas more efficient and effective particularly at a turbulent time like the present. Introduction ome facts of history have been so romanticized that it would be hard to know fact from fiction. British advent into the Indo-Pakistan S subcontinent and their north-western expansion right up to the hard and inhospitable hills on the Western Frontier of Pakistan is a story that would look unbelievable today if one were to imagine the wildness of the territory in those times. The most fascinating aspect of the British rule in the Indian Subcontinent is their dealing with the fierce and warlike tribesmen of the northwest frontier and keeping their land under their effective control till the very end of their rule in India. -

Peshawar Torkham Economic Corridor Project

Peshawar Torkham Economic Corridor Project Public Disclosure Authorized Safeguard Instruments Component I – ESIA and RAP Component II – EMF, RPF and SMF EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2018 Safeguard Instumengts of the Peshawar-Torkham Economic Corridor Project Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Background of the Peshawar – Torkham Economic Corridor ........................................ 4 1.2 Components of the Proposed Project ........................................................................... 5 2 Legal and Regulatory Requirements ......................................................................... 6 2.1 Applicable National Regulatory Requirements .............................................................. 6 2.2 The World Bank .............................................................................................................. 8 2.2.1 Category and Triggered Policies .................................................................................... 8 3 Description of the Project ........................................................................................ 9 3.1 Project Area ................................................................................................................... 9 3.2 Component I Peshawar – Torkham Expressway Project Description ............................ 9 3.2.1 Project Design -

Tribal Belt and the Defence of British India: a Critical Appraisal of British Strategy in the North-West Frontier During the First World War

Tribal Belt and the Defence of British India: A Critical Appraisal of British Strategy in the North-West Frontier during the First World War Dr. Salman Bangash. “History is certainly being made in this corridor…and I am sure a great deal more history is going to be made there in the near future - perhaps in a rather unpleasant way, but anyway in an important way.” (Arnold J. Toynbee )1 Introduction No region of the British Empire afforded more grandeur, influence, power, status and prestige then India. The British prominence in India was unique and incomparable. For this very reason the security and safety of India became the prime objective of British Imperial foreign policy in India. India was the symbol of appealing, thriving, profitable and advantageous British Imperial greatness. Closely interlinked with the question of the imperial defence of India was the tribal belt2 or tribal areas in the North-West Frontier region inhabitant by Pashtun ethnic groups. The area was defined topographically as a strategic zone of defence, which had substantial geo-political and geo-strategic significance for the British rule in India. Tribal areas posed a complicated and multifaceted defence problem for the British in India during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Peace, stability and effective control in this sensitive area was vital and indispensable for the security and defence of India. Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 1 Arnold J. Toynbee, „Impressions of Afghanistan and Pakistan‟s North-West Frontier: In Relation to the Communist World,‟International Affairs, 37, No. 2 (April 1961), pp. -

Sectarian Violence in Pakistan's Kurram Agency

Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) Brief Number 40 Sectarian Violence in Pakistan’s Kurram Agency Suba Chandran 22nd September 2008 About the Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) The Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) was established in the Department of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford, UK, in March 2007. It serves as an independent portal and neutral platform for interdisciplinary research on all aspects of Pakistani security, dealing with Pakistan's impact on regional and global security, internal security issues within Pakistan, and the interplay of the two. PSRU provides information about, and critical analysis of, Pakistani security with particular emphasis on extremism/terrorism, nuclear weapons issues, and the internal stability and cohesion of the state. PSRU is intended as a resource for anyone interested in the security of Pakistan and provides: • Briefing papers; • Reports; • Datasets; • Consultancy; • Academic, institutional and media links; • An open space for those working for positive change in Pakistan and for those currently without a voice. PSRU welcomes collaboration from individuals, groups and organisations, which share our broad objectives. Please contact us at [email protected] We welcome you to look at the website available through: http://spaces.brad.ac.uk:8080/display/ssispsru/Home Other PSRU Publications The following papers are freely available through the Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) • Report Number 1. The Jihadi Terrain in Pakistan: An Introduction to the Sunni Jihadi Groups in Pakistan and Kashmir • Brief number 32: The Political Economy of Sectarianism: Jhang • Brief number 33. Conflict Transformation and Development in Pakistan’s North • Western Territories • Brief number 34. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

AFRIDI Colonel Monawar Khan

2019 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER A CONCISE BIOGRAPHY OF: COLONEL M. K. AFRIDI A concise biography of Colonel Monawar Khan AFRIDI, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P., D.T.M. & H., who was an officer in the Indian Medical Service between 1924 and 1947; and a distinguished physician in Pakistan after the Second World War. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2019) 1 December 2019 [COLONEL M. K. AFRIDI] A Concise Biography of Colonel M. K. AFRIDI Version: 3_1 This edition dated: 1 December 2019 ISBN: Not yet allocated. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. (copyright held by author) Published privately by: The Author – Publishing as: www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk 1 1 December 2019 [COLONEL M. K. AFRIDI] Colonel Monawar Khan AFRIDI, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P., D.T.M. & H., Indian Medical Service. For an Army to fight a campaign successfully, many different aspects of military activity need to be in place. The soldiers who do the actual fighting need to be properly trained, equipped, supplied, and importantly for the individual soldiers, they need to know that in the event of them being wounded (which is more likely than not), they will receive the best medical treatment possible. In South East Asia, more soldiers fell ill than were wounded in battle, and this fact severely affected the ability of the Army to sustain any unit in the front line for any significant period. -

Police Organisations in Pakistan

HRCP/CHRI 2010 POLICE ORGANISATIONS IN PAKISTAN Human Rights Commission CHRI of Pakistan Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative working for the practical realisation of human rights in the countries of the Commonwealth Human Rights Commission of Pakistan The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) is an independent, non-governmental organisation registered under the law. It is non-political and non-profit-making. Its main office is in Lahore. It started functioning in 1987. The highest organ of HRCP is the general body comprising all members. The general body meets at least once every year. Executive authority of this organisation vests in the Council elected every three years. The Council elects the organisation's office-bearers - Chairperson, a Co-Chairperson, not more than five Vice-Chairpersons, and a Treasurer. No office holder in government or a political party (at national or provincial level) can be an office bearer of HRCP. The Council meets at least twice every year. Besides monitoring human rights violations and seeking redress through public campaigns, lobbying and intervention in courts, HRCP organises seminars, workshops and fact-finding missions. It also issues monthly Jehd-i-Haq in Urdu and an annual report on the state of human rights in the country, both in English and Urdu. The HRCP Secretariat is headed by its Secretary General I. A. Rehman. The main office of the Secretariat is in Lahore and branch offices are in Karachi, Peshawar and Quetta. A Special Task Force is located in Hyderabad (Sindh) and another in Multan (Punjab), HRCP also runs a Centre for Democratic Development in Islamabad and is supported by correspondents and activists across the country. -

THE WAZIRISTAN ACCORD Evagoras C

THE WAZIRISTAN ACCORD Evagoras C. Leventis* The Waziristan Accord between Pakistan’s government and tribal leaders in that country’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) has failed not only to curb violence in the immediate region but also to restrict cross-border militant activity--including resurgent Taliban and al-Qa’ida cadres-- between Pakistan’s “tribal belt” and Afghanistan. The purpose of this article is to examine the Waziristan Accord and to indicate why agreements of this nature will continue to fail unless there is a substantial modification in Pakistan’s internal and regional policies. On September 5, 2006, in the town of eradicating the presence of foreign militants in Miranshah, on the football field of the the area.3 However, even a cursory monitoring Government Degree College, Maulana Syed of the situation since the September 2006 Nek Zaman, a member of the National agreement indicates that the former is Assembly for the North Waziristan Agency probably closer to the truth. Nevertheless, and a tribal council member, read out an describing the Waziristan Accord as an agreement between the Pakistani government “unconditional surrender” is probably too and tribal elders that has since been known as extreme a characterization, since the the Waziristan Accord. The agreement, government of Pakistan hardly surrendered witnessed by approximately 500 elders, anything but rather reaffirmed the status quo-- parliamentarians, and government officials, a state of affairs that certain segments of the was signed on behalf of the Pakistan Pakistani administration do not consider to be government by Dr. Fakhr-i-Alam, a political adverse but rather vital to Pakistan’s greater agent of North Waziristan, tribal and militia strategic interests.4 leaders from the mainly Pashtun tribes and This article is divided into two sections. -

Taliban and Anti-Taliban

Taliban and Anti-Taliban Taliban and Anti-Taliban By Farhat Taj Taliban and Anti-Taliban, by Farhat Taj This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Farhat Taj All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2960-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2960-1 Dedicated to the People of FATA TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... ix Preface........................................................................................................ xi A Note on Methodology...........................................................................xiii List of Abbreviations................................................................................. xv Chapter One................................................................................................. 1 Deconstructing Some Myths about FATA Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 33 Lashkars and Anti-Taliban Lashkars in Pakhtun Culture Chapter Three ...........................................................................................