WPL 17 May 1974 Iv.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record-Mirror-1978-1

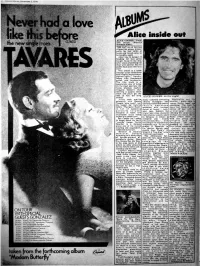

Record Mora, December 2. 1978 Alice inside out rr ALICE COOPER: 'From The Inside' (Warner Brothers K5677) t , t- THE BAT out of hell has clipped his wings, thrown sz away his last bottle of 1 booze and vowed never to be nAughty again. s Alice was In danger of A heading for that great boogie house In the sky, after years of pickling his Si liver with alcohol. But he pulled back and went on a cure. This album Is a loose a. concept of his reflections . and hospital experiences. t Apocalyptic tracks, , -k heavy with thunderous , II guitar and keyboards. The title track is a panoramic view of being on the road and how the booze troubles started. Imagine 'School's Out' meeting a quality disco track and you'll get the 'idea of how the song on the wagon sounds. ALICE COOPER: Alice now works many assorted seventies Highlights are the primarily with Bernie albums Rundgren has cocktail - piano intro to Taupin, who hasn't lost cleverly fused mid -sixties 'never Never Land' and his talent for incisive idyllic American emotional 'The Verb To lyrics. 'The Quiet Room' melodies with various Love' but 'Hello It's Me' Is full of opposing forms of heavy - rock. comes off best with Its parallels between soul; jazz, Eastern In- archetypal chorus thoughts of home and trigue and even modern utilising the vocal talents frustration about being Instrumental pieces akin of Hall and Oates, Stevie n M locked in a padded cell. to Debussy to create a Nicks (when she's not But Cooper isn't going complete 'pop - sound with her group she's to forget about his early encyclopaedia', and alright) and Rick "weirdo" Image. -

AYELET GIL-EFRAT Editor

AYELET GIL-EFRAT Editor Feature Films: THE OVEN - NEM Corp – Jake Paltrow, director; Oren Moverman, producer DOOSRA – Ramesh Deo Productions – Abhinay Deo, director LUST LIFE LOVE – 1091 Pictures – Stephanie Sellar & Ben Feuer, directors Berlin International Film Festival, World Premiere HARMONIA – KESHET – Ori Sivan, director Jerusalem International Film Festival Winner, Jewish Experience Award NO EXIT – Cia.La Salamandra – Dror Sabu, director Jerusalem International Film Festival Winner, Best Film Television: SMALL MONSTERS – Reshet – director, Dani Sirkin LOST IN ASIA – YES Cable Network– Yuval Shefferman, director THE PLAGUE – HOT Cable Network– Yami Wisler, director LOST IN ASIA – YES Cable Network– Yuval Shefferman, director EAGLES (NEVELOT) – HOT Cable Network– Dror Sabu, director BAREFOOT – HOT Cable Network– Ori Sivan, director THE FIRST FAMILY – HOT Cable Network– Alon Bennary, director THE SADDEST SKETCH SHOW IN THE WORLD – Channel 10 – Yammi Wisler, director UNTIL THE WEDDING – Channel 2 / RESHET – Daphna Levin & Oded Lotan, directors NOT IN FRONT OF THE CHILDREN – Channel 10 – Eyal Sella, director I NEVER PROMISED YOU –YES Cable Network–Gabi Biblyovich & Ophir Babayof, directors Unscripted: 90 HIGHWAY – Channel 8 – director, Anat Seltzer PAIRS – Channel 3 / HOT Cable Network – director, Adva Sheffer Y AT TEN – YES Cable Network – various directors Y PROJECT – YES Cable Network – director, Dror Sabu Documentaries: ALEX IN WONDERLAND – Channel 8 – director, Ori Sivan STRUDEL WITH TAHINI – YES Cable Network – director, Tomer Shani & Ran Landau IN THE JEWISH STATE – Channel 1 – directors, Gabi Biblyovich, Anat Seltzer, & Moish Goldberg MOTHER OF THE BAND – Channel 3 / HOT Cable Network – directors, Shahar Magen & Ayelet Gil-Efrat VOICE OF THE LAND – Channel 10 – director, Eyal Halfon RED DAYS – Channel 2 / TELAD – director, Dror Sabu 9465 Wilshire Blvd. -

Todd Rundgren: “Back to the Bars ”

Serving DeKalb Community College Vol. \A Friday, March 30, 1979 Page 1 Scott is just not a good businessman.” This week’s edition of The Open Door is only four pages in length because of the Spring break. The paper will return to its —John Truelove regular 8-page editions starting next week. Photo by B. Maher A* by Bill Maher According to a report in Activity Calander the Thursday, March 22,1979 issue of the Atlanta Journal, The following is a list of the already scheduled activities for the chairman of the DeKalb the month of April. County School Board will not April support the renewal of 3 - InterClub Council Meeting. 2:15 p.m r President W. Wayne Scott’s 3 - Student Government Association Meeting. 3:15 p.m. contract for another year. 10 - Student Government Association meeting. 3:15 p.m School Board Chairman 11 - Tech Rap Committee - Technical Division and College Trustee John Truelove told the Journal Spring Fling. 11:00 (activities hour) that, "Dr. Scott is just not a 17 - InterClub Council meeting. 2:15 p.m. good businessman.” 17 - Student Government Association. 3:15 p.m. Truelove also said that the 18 - Inter-Varsity sponsors a contemporary gospel concert. school board urged Scott to 11:00 a.m. place his children in public 24 - Student Government Association meeting. 3:15 p.m. school soon after he was 25 - Club meetings hired. Scott complied with the wishes of the board but- President Scott. Is his job on the line? put the children back into told us he was doing it.” Board has no stated policy SGA Meetings private schools last Dr. -

IITEBPBIS Cunningham Is an Active Volved in Many Shreve Member of the Rifle Team·, Activities

1978-79 ... A year to remember by Missy Falbaum get parents more involved with the first female in the history The 1978-79 school year was their children in school. of Captain Shreve to be one full of pep rallies, football , The Caddo Parish School appointed Cadet Corps Com games, plays, a talent show, the Board passed a mandatory mander in the JROTC program. EXCEL program, and many suspension for anyone using or The Student Counci I spon new changes at Captain Shreve. possessing tobacco on any school sored many intermural sports campus or school bus. activities throughout the year. Probably the newest change at A new diploma variation was They were also in charge of the CS was the ruling passed by the adopted which will now award an canned food drive, blood donor school board which required "Honors with Excellence" drive, and the Easter Seal drive. high school students in Caddo diploma to graduating seniors Also Student Council Week Parish to start classes an hour who have a more difficult brought with it speakers, and earlier than in the previous curriculum. many spirited activities. year. This program did allow The drama department put in It was also a year for such students who took six classes to three talent-packed plays which memorable events as Showboat leave school at 2:15 . dealt with such topics as drug '79, Sadie Hawkins, home Captain Shreve was one of the addicts, Saint Bernadette, and coming, and the prom. area schools that became in a dance marathon. 1ndeed the past year at volved in the EXCEL program. -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

Nostalgia, Utopia, and Desire in the New York Lesbian Bar

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2019 “It’s your future, don’t miss it”: nostalgia, utopia, and desire in the New York lesbian bar Zoe Wennerholm Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Wennerholm, Zoe, "“It’s your future, don’t miss it”: nostalgia, utopia, and desire in the New York lesbian bar" (2019). Senior Capstone Projects. 897. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/897 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “It’s Your Future, Don’t Miss It”: Nostalgia, Utopia, and Desire in the New York Lesbian Bar Zoe Wennerholm April 26, 2019 Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in Urban Studies ________________________ Advisor, Lisa Brawley Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………….3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter 1: History: A Brief Review of Lesbian Bars in the 20th and 21st Century American Urban Landscape……………………………………………………………………………9 Chapter 2: Loss: Lesbian Bar Closings and Their Affective Reverberations………………29 Chapter 3: Desire: The Lesbian Bar in the Queer Imaginary……………………………….47 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….52 References Cited……………………………………………………………………………55 Appendix 1: Interview with Gwen Shockey…………………………………………………60 Appendix 2: Timeline of New York Lesbian Bars…………………………………………73 2 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Professor Lisa Brawley, whose guidance and encouragement always came at exactly the right time. My heartfelt thanks also goes to Gwen Shockey, whose enthusiasm and willingness to speak with a naïve young dyke made me feel understood and inspired. -

Schools out JAM SKIDS CLASH

December 2 1978 18p '&3 AC/DC Schools out JAM SKIDS CLASH ,.z17.) "e -t -g a+l!! __ T TT T TrTIT TTrTr r .TT rl Recoed Mirror, December 2, 1978 4 r UK 1 4 DO VA THINK I M SEXY, Rod Stewart Rhra I 1 UK,ieuttc GREASE. Original Soundtrack RSO SIM 2 1 RAT TRAP, Boomtown Rats US Ensign 2 28 JAZZ, Oueen USALBUMS EMI 3 2 HOPELESSLY DEVOTED TO YOU. 1 4 YOU DON'T BRING ME Otrv,a Newton -John RSO 3 7 FLOWERS. Streisand/Diamond 20 GOLDEN GREATS, Neil Diamond MCA 1 1 57ND STREET, Bey Joel Columbia 4 3 MY BEST FRIENDS GIRL, Cars Columbia Elekva 4 3 EMOTIONS, Vannes K -Tel 2 2 UVE AND MORE. Don na Summer Casablanca 5 9 HANGING P 2 1 MacARTHUR PARK, ON THE TELEPHONE, Donna Summer Blondie Chrysalis 5 2 GIVE EM ROPE, The Casablanca ENOUGH Clash CBS 3 4 A WILD AND CRAZY GUY, Steve Martin Warner Bros 3 3 HOW 6 5 PRETTY UTTLE ANGEL EYES. Showaddywaddy Anola MUCH I FEEL, Ambrosia Warner Bros 6 36 LION HEART, Kate Bush EMI 4' 3 DOUBLE VISION, Foreigner Arantic 7 MARY'S CHILD. 4 6 LE FREAK, Chic - BOY Boney M Adanric/Hansa 7 MIDNIGHT Atlantic 22 HUSTLE, Various Kid 5 5 GREASE, Soundtrack RSO 8 8 INSTANT REPLAY, Dan Hartman 5 7 I JUST WANNA STOP, Gino Vennelll A&M Blue Sky 8 4 LIVE. Manhavan Transfer Atlantic 6 7 PIECES OF EIGHT, Styx AEM 9 25 I LOST MY HEART TO A STARSHIP TROOPER, 6 2 DOUBLE VISION, Foreigner Atlantic 9 12 TONIC FOR THE TROOPS, Boomtown Rats Ensign 7 - GREATEST HITS, VOL II, Bamra Svesard Sarah Hot Columba Brightman Gasp Molls 7 8 I LOVE THE NIGHT LIFE, Alicia Bridges Polydor 10 5 25TH ANNIVERSARY ALBUM, Shirley Hassey United Artists 8 9 ,COMES A TIME Ned Young Warner Bros 10 6 DARLIN' Frank,. -

Todd Rundgren Information

Todd Rundgren I have been a Todd Rundgren fan for over 40 years now. His music has helped me cope with many things in my life including having RSD and now having an amputation. I feel that Todd is one of the most talented musician, song writer and music producer that I have ever met in my life. If you have ever heard Todd's music or had an opportunity to see Todd in concert, you will know what I mean. Most people do not know who Todd Rundgren is. Most people say Todd who? Todd's best-known songs are "Can We Still Be Friends," "Hello, It's Me" "I Saw the Light," "Love is the Answer," and "Bang on the Drum All Day" (this is the song that you hear at every sporting event). Todd is also known for his work with his two bands Nazz and Utopia, while producing records for artists such as Meat Loaf, Hall and Oats, Grand Funk Railroad, Hiroshi Takano, Badfinger, XTC, and the New York Dolls. Eric and Todd Rundgren in Boston, MA February 4, 1998 Eric and Todd Rundgren in Salisbury, MA September 14, 2011 Eric and Michele Rundgren in Salisbury, MA September 14, 2011 Eric and Todd Rundgren in S. Dartmouth, MA October 20, 2012 Todd News Todd Rundgren Concert Tour Dates Please click on the following link below to view Todd's concert tour dates. http://www.todd-rundgren.com/tr-tour.html http://www.rundgrenradio.com/toddtours.html To view a recent concert that Todd did in Oslo, Norway please click on the following link: http://www1.nrk.no/nett-tv/klipp/503541 Todd Rundgren Concert Photo's Photo By: Eric M. -

Westminsterresearch

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Palestinian filmmaking in Israel : negotiating conflicting discourses Yael Friedman School of Media, Arts and Design This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2010. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel: Negotiating Conflicting Discourses Yael Friedman PhD 2010 Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel: Negotiating Conflicting Discourses Yael Friedman A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Acknowledgments The successful completion of this research was assisted by many I would like to thank. First, my thanks and appreciation to all the filmmakers and media professionals interviewed during this research. Without the generosity with which many shared their thoughts and experiences this research would have not been possible. -

Branded Reality the Rise of Embedded Branding ('Branded Content'): Implications for the Cultural Public Sphere

GOLDSMITHS UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Branded Reality The Rise of Embedded Branding (‘Branded Content’): Implications for the Cultural Public Sphere Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Media and Communications By Anat Balint P a g e | 1 Acknowledgments This thesis has been an intellectual challenge, and much more than that: it was a personal journey and a phase of transformation. This was a shift from the world of investigative journalism to that of scholarly work, from writing 1000 words in one afternoon to creating a narrative of tens of thousands of words over many many months, from the hectic life of a daily reporter to the silent, somewhat isolating routine of a writer with a laptop. Moreover, it was a process of finding a voice and making my arguments heard. Hopefully, these efforts were somewhat successful, as during the work on the thesis, a time that was also devoted to various public activities as well as teaching and writing, the topic of embedded branding became, in my local arena at least, the subject of investigative reporting by other journalists, heated public debate, policy reports and a legislation proposal. I am most thankful to all those who were with me on this journey. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors, Prof. Nick Couldry and Dr. Liz Moor. Prof. Couldry guided me through the early stages of the research, in its London phase, and was most helpful in setting its theoretical and methodological infrastructure. His immense knowledge, critical point of view and passion for the field are an inspiration to any young scholar. -

Awards Feature Length Films

birth: 28.10.72 in Jerusalem Nationality: Israeli, German. Languages: Native speaker of Hebrew and German Fluent English.Avid, Final cut, 16/35 mm,A.B roll. Awards 1. Prize Wolgin award, .Film Festival Jerusalem („Bil’in Habibti“). Special Mention Rotterdam Filmfestival. („Bil’in Habibti“). Grand Prix Sarajevo Filmfestival (“Free Flow”) Other Israel Award Haifa International Film Festival (“Free Flow”) . Rias television award (“Brown Babies”) Editing prize of the Israeli Film Instutute („Winker“). Unesco Prize („Vilonot“, „Courtains“) Main prize of the Student Jury, 14e Festival international Signes de Nuit, Paris („Counterlight“) 1. prize Haifa Filmfestival („Vilonot“ – „Courtains“) German Celeste Art Prize, Berlin. („Mother Economy“) Best foreign Film Pecs Festival, Jury Prize Pecs Festival („Mother Economy“) Feature Length Films 2018 Yes Doku/New Israeli Film Fund „Cause Of Death“. Script/Development/Rough Cut (90 min) Dir: Ramy Katz; Jerusalem International film Festival https://jff.org.il/he/movie/21820 2013 - 2017 Saga Media Berlin/ Köln "Die Mitte der Nacht ist der Anfang vom Tag" (84 min Dir:Michaela Kirst) http://aok-bv.de/engagement/index_16618.html Wildart Vienna/ Filmtank Hamburg/ Sagamedia Berlin „Green“ (in Post-Produktion Dir: Michaela Kirst) The New Israeli Film Fund “Nobody home” (59 min Dir Michal Ben Tovim) http://www.7thart.com/films/Nobody-Home 2011 Second Channel Autority/ The new Israeli Film Fund „Free Flow“ (65 min, Dir. Rami Katz. Grand Prix Sarajevo Festival. Other Israel Award Haifa international Film Festival) -

February 26 March 4

FEBRUARY 26 ISSUE MARCH 4 Orders Due January 29 5 Orders Due February 5 axis.wmg.com 2/23/16 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Hawkwind Space Ritual (2LP 180 Gram Vinyl) PRH A 825646120758 407156 34.98 1/22/16 Jethro Tull Living In The Past (2LP 180 Gram Vinyl) PRH A 825646041930 551965 34.98 1/22/16 Morrissey Bona Drag (2LP) RRW A 825646775545 542347 34.98 1/22/16 Red Hot Chili Peppers I'm With You (2LP) WB A 093624924340 551828 29.98 1/22/16 Red Hot Chili Peppers Stadium Arcadium (4LP) WB A 093624439110 44391 39.98 1/22/16 Last Update: 01/05/16 For the latest up to date info on this release visit axis.wmg.com. ARTIST: Hawkwind TITLE: Space Ritual (2LP 180 Gram Vinyl) Label: PRH/Rhino/Parlophone Config & Selection #: A 407156 Street Date: 02/23/16 Order Due Date: 01/22/16 UPC: 825646120758 Box Count: 20 Unit Per Set: 2 SRP: $34.98 Alphabetize Under: H TRACKS Full Length Vinyl 1 Side A Side B 01 Earth Calling 01 Lord Of Light 02 Born To Go 02 Black Corridor 03 Down Through The 03 Space Is Deep Night 04 Electronic No 1 04 The Awakening Full Length Vinyl 2 Side A Side B 01 Orgone Accumulator 01 Seven By Seven 02 Upside Down 02 Sonic Attack 03 10 Seconds Of Forever 03 Time We Left This World 04 Brainstorm Today 04 Master Of The Universe 05 Welcome To The Future ALBUM FACTS Genre: Rock Description: Recorded live in December 1972 and released the following year, Space Ritual is an excellent document of Hawkwind's classic lineup, underscoring the group's status as space rock pioneers.