Westminsterresearch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Transnational Media Flow in Nusantara: Cross-Border Content Broadcasting in Indonesia and Malaysia

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 2, September 2011 Revisiting Transnational Media Flow in Nusantara: Cross-border Content Broadcasting in Indonesia and Malaysia Nuurrianti Jalli* and Yearry Panji Setianto** Previous studies on transnational media have emphasized transnational media organizations and tended to ignore the role of cross-border content, especially in a non-Western context. This study aims to fill theoretical gaps within this scholarship by providing an analysis of the Southeast Asian media sphere, focusing on Indonesia and Malaysia in a historical context—transnational media flow before 2010. The two neighboring nations of Indonesia and Malaysia have many things in common, from culture to language and religion. This study not only explores similarities in the reception and appropriation of transnational content in both countries but also investigates why, to some extent, each had a different attitude toward content pro- duced by the other. It also looks at how governments in these two nations control the flow of transnational media content. Focusing on broadcast media, the study finds that cross-border media flow between Indonesia and Malaysia was made pos- sible primarily in two ways: (1) illicit or unintended media exchange, and (2) legal and intended media exchange. Illicit media exchange was enabled through the use of satellite dishes and antennae near state borders, as well as piracy. Legal and intended media exchange was enabled through state collaboration and the purchase of media rights; both governments also utilized several bodies of laws to assist in controlling transnational media content. Based on our analysis, there is a path of transnational media exchange between these two countries. -

Gerald Van Der Kaap

Kunsthaus Graz, Lendkai 1, 8020 Graz, Austria [email protected] T. +43 / (0) 316 / 81 55 500, F. 81 55 509 www.camera-austria.at Bleiben oder gehen / Ostati ili otići / Staying or leaving Eröffnung: Freitag, 8. Oktober 2004 Ausstellungsdauer: 9. August bis 28. November 2004 Biografien der TeilnehmerInnen / biographies of the participants Ana Hušman 1977 Geboren in / Born in Zagreb. Lebt und arbeitet in Zagreb, Kroatien / Living and working in Zagreb, Croatia. Ausbildung / Education 2002 Abschluss in Multimedia Art und Kunsterziehung an der Akademie der bildenden Künste in Zagreb / Graduate in multimedia art and paedagogics from the Academy of Fine Arts, Zagreb. Stipendien und Preise / Scholarships and Awards 2003 "Home", Visura aperta / Momiano 03, Momjan "Meršpajz", Alternative Film and Video 03 Festival, Belgrade 2000 CEEPUS student exchange grant, FAVU, Brno, Czech Republic 1999 CEEPUS student exchange grant, Academy of Fine Arts, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Ausstellungen und Projektionen / Exhibitions and screenings 2004 27. salon mladih (27th Salon of Young Artists), HDLU (Hrvatsko društvo likovnih umjetnika), Zagreb U prvom licu, HDLU, Zagreb C8.H11.N, Galerija Vladimir Nazor, Zagreb Alternative Film and Video 03 Festival, Belgrade "Side-effects", Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade "Share", Galerija P74, Ljubljana 13. dani hrvatskog filma (13th Review of Croatian Film), Zagreb 2003 12. dani hrvatskog filma (12th Review of Croatian Film), Zagreb "All The Extras" (mit / with Lala Raščić), Galerija Močvara, Zagreb "Cross Tree" ( mit / with Ana Šerić), Galerija Nova, Zagreb "On my Tram Stop", Urban Festival, Ad hoc 1, Zagreb "Visura aperta / Momiano 03", Festival vizualnih i audio medija (Festival of Visual and Audio Media), Momjan "Much too much", Umjetnički paviljon (Art Pavilion), Zagreb 2002 Les films du dimanche de l'Institut Français d'Architecture, 11. -

Hagar: the Association for the Advancement of Cultural Pluralism

Dr. Tal Ben Zvi CURRICULUM VITAE AND LIST OF PUBLICATIONS 1. Personal Details Dr. Tal Ben Zvi MA Policy and Theory of Arts Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem 972-54-7696810 [email protected] 2. Education 2010-2011 Post-doc, Truman Institute for the Advancement of Peace The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 2010 PhD Doctoral thesis at Tel Aviv University on "Representations of the Nakba in the Palestinian art of the 1970s and 1980s, as reflected in the work of artists who belong to the Palestinian minority in Israel" [Supervisors: Profs. Hanna Taragan and Moshe Zuckermann] 1999-2004 MA Summa Cum Lauda, The Yolanda and David Katz Faculty of the Arts - Graduate School, Tel Aviv university. her thesis was titled: “Between Nation and Gender: The Representation of the Female Body in Palestinian Art". 1995-1997 The new seminar for visual culture: Criticism and Curatorship program, Camera Obscura College, Tel Aviv. 1989-1992 B.A. fine arts and art history, Art department , Haifa university. 3. Employment History (a) Positions in academic 2015 Lecturer, MA Policy and Theory of Arts Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem Senior lecturer (Tenured position) [Hebrew: "Martze Bakhir"] 2012-2015 Vice President for Academic Affaires Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem 2009-2010 Head of the School of Arts, Kibbutzim College of Education Kibbutzim College of Education is the largest teaching college in Israel. The School of Arts includes the fields of theatre, dance, media and cinema, design and art. The school is attended by 600 B.Ed and diploma students. -

500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES

500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES SYNOPSIS 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N is a documentary about the Palestinian village of Ayn Hawd which was captured and depopulated by Israeli forces in the 1948 war and subsequently transformed into a Jewish artist's colony and renamed Ein Hod. It tells the story of the village's original inhabitants who, after expulsion, settled only 1.5 kilometers away in the outlying hills. Since Israeli law prevents Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes, the refugees of Ayn Hawd established a new village: “Ayn Hawd al-Jadida” (The New Ayn Hawd). Ayn Hawd al-Jadida is an unrecognized village, which means that it receives no services such as electricity, water, or an access road. Relations between the artists and the refugees are complex: unlike most Israelis, the residents of Ein Hod know the Palestinians who lived there before them, since the latter have worked as hired hands for the former. Unlike most Palestinian refugees, the residents of Ayn Hawd al-Jadida know the Israelis who now occupy their homes, the art they produce, and the peculiar ways they try to deal with the fact that their society was created upon the ruins of another. It echoes the story of indigenous peoples everywhere: oppression, resistance, and the struggle to negotiate the scars of the past with the needs of the present and the hopes for the future. Addressing the universal issues of colonization, landlessness, housing rights, gentrification, and cultural appropriation in the specific context of Israel/Palestine, 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N documents the art of dispossession and the creativity of the dispossessed. -

Using Structured Observation and Content Analysis to Explore the Presence of Older People in Public Fora in Developing Countries

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Aging Research Volume 2014, Article ID 860612, 12 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/860612 Research Article Using Structured Observation and Content Analysis to Explore the Presence of Older People in Public Fora in Developing Countries Geraldine Nosowska,1 Kevin McKee,2 and Lena Dahlberg2,3 1 Effective Practice Ltd., 8 Bridgetown, Totnes, Devon TQ95AB, UK 2School of Education, Health and Social Studies, Dalarna University, 791 88 Falun, Sweden 3Aging Research Centre, Karolinska Institutet and Stockholm University, Gavlegatan¨ 16, 113 30 Stockholm, Sweden Correspondence should be addressed to Lena Dahlberg; [email protected] Received 15 September 2014; Revised 10 November 2014; Accepted 10 November 2014; Published 8 December 2014 AcademicEditor:F.R.Ferraro Copyright © 2014 Geraldine Nosowska et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. There is a lack of research on the everyday lives of older people in developing countries. This exploratory study used structured observation and content analysis to examine the presence of older people in public fora and considered the methods’ potential for understanding older people’s social integration and inclusion. Structured observation occurred of public social spaces in six cities each located in a different developing country and in one city in the United Kingdom, together with content analysis of the presence of people in newspaper pictures and on television in the selected countries. Results indicated that across all fieldwork sites and data sources, there was a low presence of older people, with women considerably less present than men in developing countries. -

AYELET GIL-EFRAT Editor

AYELET GIL-EFRAT Editor Feature Films: THE OVEN - NEM Corp – Jake Paltrow, director; Oren Moverman, producer DOOSRA – Ramesh Deo Productions – Abhinay Deo, director LUST LIFE LOVE – 1091 Pictures – Stephanie Sellar & Ben Feuer, directors Berlin International Film Festival, World Premiere HARMONIA – KESHET – Ori Sivan, director Jerusalem International Film Festival Winner, Jewish Experience Award NO EXIT – Cia.La Salamandra – Dror Sabu, director Jerusalem International Film Festival Winner, Best Film Television: SMALL MONSTERS – Reshet – director, Dani Sirkin LOST IN ASIA – YES Cable Network– Yuval Shefferman, director THE PLAGUE – HOT Cable Network– Yami Wisler, director LOST IN ASIA – YES Cable Network– Yuval Shefferman, director EAGLES (NEVELOT) – HOT Cable Network– Dror Sabu, director BAREFOOT – HOT Cable Network– Ori Sivan, director THE FIRST FAMILY – HOT Cable Network– Alon Bennary, director THE SADDEST SKETCH SHOW IN THE WORLD – Channel 10 – Yammi Wisler, director UNTIL THE WEDDING – Channel 2 / RESHET – Daphna Levin & Oded Lotan, directors NOT IN FRONT OF THE CHILDREN – Channel 10 – Eyal Sella, director I NEVER PROMISED YOU –YES Cable Network–Gabi Biblyovich & Ophir Babayof, directors Unscripted: 90 HIGHWAY – Channel 8 – director, Anat Seltzer PAIRS – Channel 3 / HOT Cable Network – director, Adva Sheffer Y AT TEN – YES Cable Network – various directors Y PROJECT – YES Cable Network – director, Dror Sabu Documentaries: ALEX IN WONDERLAND – Channel 8 – director, Ori Sivan STRUDEL WITH TAHINI – YES Cable Network – director, Tomer Shani & Ran Landau IN THE JEWISH STATE – Channel 1 – directors, Gabi Biblyovich, Anat Seltzer, & Moish Goldberg MOTHER OF THE BAND – Channel 3 / HOT Cable Network – directors, Shahar Magen & Ayelet Gil-Efrat VOICE OF THE LAND – Channel 10 – director, Eyal Halfon RED DAYS – Channel 2 / TELAD – director, Dror Sabu 9465 Wilshire Blvd. -

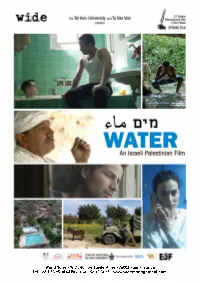

WATER-Presskit-06.09.2012.Pdf

World Sales - WIDE 40, rue Sainte Anne - 75002 Paris - France Tel. +33 1 53 95 04 64 Fax: +33 1 53 95 04 65 - www.widemanagement.com water pages corrigées_water 14/08/12 14:33 Page2 A FEATURE FILM BORN OUT OF A UNIQUE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN COOPERATION THE FILM HD, 120 minutes, color, original version : Arabic, Hebrew, English Produced by the Film and Television department of the Tel Aviv University In association with Tu Vas Voir. The project WATER is a cinematic coope- WATER exemplifies cinema's ability to ration created within the Department of penetrate forbidden zones. This movie Film and Television at Tel-Aviv University. In make us, Israelis and Palestinians, rea- 2012, a small group of Israeli and Palesti- lize that we all yearn for a solution. nian filmmakers directed a feature film with total artistic freedom, exploring a strongly unifying subject: WATER. Yael Perlov Project initiator and Artistic Director Tel Aviv University WATER is a poetic and pastoral subject, but one that is also very political as well as violent in the context of the Israel-Palestine conflict. WATER belongs to two conflicting popula- tions, who seldom manage to overcome prejudice and political intimidation, but have found a platform for a unique colla- boration, in the form of this feature film. STILL WATERS - By an ancient spring near Jerusalem, an Israeli couple finds a quiet moment away from the rat race of Tel Aviv life. The cool water spring is also used by a group of Palestinians heading to their jobs in Israel. At high noon, they are forced to look each other in the eye. -

Investigating Kuwaiti Television Serial Dramas of Ramadan: Social Issues and Narrative Forms Across Three Transformative Production Eras

Investigating Kuwaiti Television Serial Dramas of Ramadan: Social Issues and Narrative Forms Across Three Transformative Production Eras Ahmad HAYAT Ph.D. Thesis 2020 Investigating Kuwaiti Television Serial Dramas of Ramadan: Social Issues and Narrative Forms Across Three Transformative Production Eras Ahmad HAYAT Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of Salford School of Arts and Media 2020 I Contents 1. Abstract …………………………………………………………………… …….. IV 2. Introduction ……………………………………………………………….……… 1 3. Literature Review ……………………………………………………………….. 12 3.1 Production Eras and Periodization ……………………………….. 13 3.2 Arab Television Eras ……………………………………………….. 24 3.3 Arab Television Programming …………………………………….. 33 3.4 Social Issues in Television Programming ………………………... 40 3.5 Narrative Forms and Formal Characteristics ……………………. 52 3.6 Conclusion …………………………………………………………… 74 4. Methodology ……………………………………………………………………... 76 4.1 Case Study Selection ………………………………………………. 78 4.2 Units of Data Collection and Analysis …………………………….. 88 4.3 Chapter Design and Approach …………………………………….. 97 4.4 Conclusion …………………………………………………………… 99 5. The Pre-Satellite Era: Al-Aqdar (1977) ……………………………………….. 101 5.1 List of Characters …………………………………………………… 102 5.2 Story Synopses and Theme Analyses …………………………… 103 5.2.1 Storyline A Synopsis ……………………………….. 104 5.2.2 Storyline A Theme Analysis ……………………….. 105 5.2.3 Storyline B Synopsis ………………………………... 106 5.2.4 Storyline B Theme Analysis ………………………... 108 II 5.2.5 Storyline C Synopsis ………………………………... 109 5.2.6 Storyline C Theme Analysis ………………………... 110 5.2.7 Storyline D Synopsis ………………………………... 111 5.2.8 Storyline D Theme Analysis ………………………... 112 5.3 Sociocultural Context ……………………………………………….. 113 5.4 Narrative Form ………………………………………………………. 122 5.5 Conclusion …………………………………………………………… 128 6. The Satellite Era: Bo Marzouq (1992) ………………………………………… 130 6.1 List of Characters …………………………………………………… 132 6.2 Story Synopses and Theme Analyses ……………………………. 132 6.2.1 Storyline A Synopsis ………………………………… 133 6.2.2 Storyline A Theme Analysis ……………………….. -

WPL 17 May 1974 Iv.Pdf

OSU WPL 17. iv-lli3 (1974); Pl!OI1E'l'IC ArlD PHOilOWGICAL PRO?BRTIES Or' CO;HiECTED 8?:EECH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Reouirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosoph:r in the Graduate Schoo} of The Ohio State University By Linda Sheekey, B.A. * * * * The Ohio State University 1973 iv Copyright by Linda Shockey 1973 V Acknowledernents 'rhe completion of this document owes a ,:.;reat deal to Professors Arnold Zwick}·, John Black, and Francis Utley vl10 p:eve me valuable advice as to refe:t-ences, to Marlene Pnyhn. who typed far be~rond the call of duty and to Professor Re.j Reddy who ir,enel'.'ously made the facilities of the Computer Science Denartment at Ca.rneeie-Mellon Universit:ir available to me, !'~specially I would like to thank my a.dYise!", Professor Ilse Lehiste, who has been a constant source of encouragement, erudition, and i.nspiration throughout my studies at Ohio State. vi Table .of Contents Acknowledgments vi List of Tables and Fip;ures · viii Chapter I • • I I * • • • • Ill • • • • • . ,• l 1.1. Research Goals 1.2, Experimental Techniques Chapter II ,;, . 1 2.1. Chanter Goals 2.2. Descri~tion of data 2.3. Theoretical considerations 2.24, List of' Processes:Found: Word Internal 2,5, Weird-boundary Insensitive Processes 2.6. External. Sandhi Processes 2.7, Discussion Chapter III • . , . • , . ·. 43 3.1. Chanter Goals 3,2, "Degree .of Reduction11 3,3, Speech Rate 3,4, Results of Speech Re.te Investip;ation 3.5. Rate Determination Procedure · 3.6. Conclusions Chanter IV 54 - 4.1. -

The Analysis of the Driving Factors of Turkish Foreign

THE ANALYSIS OF THE DRIVING FACTORS OF TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY FROM ASSERTIVENESS TO PRAGMATISM IN CASE OF TURKEY – ISRAEL RECONCILIATION ON THE MAVI MARMARA FLOTILLA INCIDENT (2010 – 2016) By MUHAMMAD ADNAN FATRON ID No. 016201300101 A Thesis presented to the Faculty of Humanities President University in partial fulfillment of the requirement of Bachelor Degree in International Relations Major in Security and Strategic Defense Studies 2017 THESIS ADVISER RECOMMENDATION LETTER Thesis entitled “THE ANALYSIS OF THE DRIVING FACTORS OF TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY FROM ASSERTIVENESS TO PRAGMATISM IN CASE OF TURKEY – ISRAEL RECONCILIATION ON THE MAVI MARMARA FLOTILLA INCIDENT (2010 – 2016)” prepared and submitted by Muhammad Adnan Fatron in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor in the Faculty of Humanities had been reviewed and found to have satisfied the requirements for a thesis fit to be examined. I therefore recommend this thesis for Oral Defense. Cikarang, Indonesia, January 24th 2017. Recommended and Acknowledged by, Drs. Teuku Rezasyah, M.A., Ph.D. i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this thesis entitled “THE ANALYSIS OF THE DRIVING FACTORS OF TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY FROM ASSERTIVENESS TO PRAGMATISM IN CASE OF TURKEY – ISRAEL RECONCILIATION ON THE MAVI MARMARA FLOTILLA INCIDENT (2010-2016)” is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, an original piece of work that has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, to another university to obtain a degree. Cikarang, Indonesia, January 24th 2017 Muhammad -

Efficiency and Rentability of Introducing DVB-T2 HEVC System in Germany and Croatia

WSEAS TRANSACTIONS on BUSINESS and ECONOMICS DOI: 10.37394/23207.2020.17.92 Fran Galetic Technological Progress in Terrestrial Television Transmitting – Efficiency and Rentability of Introducing DVB-T2 HEVC System in Germany and Croatia FRAN GALETIC Faculty of Economics and Business University of Zagreb Trg J.F. Kennedyja 6, 10000 Zagreb CROATIA Abstract: - Germany and Croatia are among first European countries that have adopted the strategy of switching from DVB-T h.264 system to DVB-T2 h.265 (HEVC) system of broadcasting for terrestrial television. The newer h.265 system has better performance compared to previously h.264 especially in terms of efficiency of transmitting. On a single frequency, h.265 enables much more data flow, which means more channels and/or better quality of transmitting. This paper investigates the efficiency and rentability of such transition and compares Germany as s big and Croatia as a small European country. The aim of the analysis is to show the background for such a technological change in these two countries and to compare it having in mind the difference of capacities necessary for terrestrial transmission. This switch to the DVB-T2 HEVC system represents the classical example of technological progress in practice, and is especially interesting in the period when other countries are setting up strategies for the future of terrestrial television transmission. Key-Words: - Terrestrial television; DVB-T; DVB-T2; HEVC; Germany; Croatia Received: August 5, 2019. Revised: September 14, 2020. Accepted: September 21, 2020. 1 Introduction resolution 720x576, while HDTV is using The most significant switch in television was the 1920x1080 resolution. -

Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: the Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films ot Facilitate Dialogue Elana Shefrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Shefrin, Elana, "Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-MEDIATING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: THE USE OF FILMS TO FACILITATE DIALOGUE by ELANA SHEFRIN Under the Direction of M. Lane Bruner ABSTRACT With the objective of outlining a decision-making process for the selection, evaluation, and application of films for invigorating Palestinian-Israeli dialogue encounters, this project researches, collates, and weaves together the historico-political narratives of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the artistic worldviews of the Israeli and Palestinian national cinemas, and the procedural designs of successful Track II dialogue interventions. Using a tailored version of Lucien Goldman’s method of homologic textual analysis, three Palestinian and three Israeli popular film texts are analyzed along the dimensions of Historico-Political Contextuality, Socio- Cultural Intertextuality, and Ethno-National Textuality. Then, applying the six “best practices” criteria gleaned from thriving dialogue programs, coupled with the six “cautionary tales” criteria gleaned from flawed dialogue models, three bi-national peacebuilding film texts are homologically analyzed and contrasted with the six popular film texts.