Annemarie Jacir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

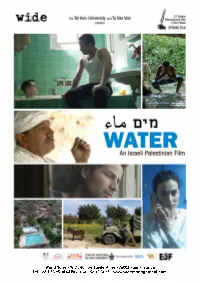

WATER-Presskit-06.09.2012.Pdf

World Sales - WIDE 40, rue Sainte Anne - 75002 Paris - France Tel. +33 1 53 95 04 64 Fax: +33 1 53 95 04 65 - www.widemanagement.com water pages corrigées_water 14/08/12 14:33 Page2 A FEATURE FILM BORN OUT OF A UNIQUE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN COOPERATION THE FILM HD, 120 minutes, color, original version : Arabic, Hebrew, English Produced by the Film and Television department of the Tel Aviv University In association with Tu Vas Voir. The project WATER is a cinematic coope- WATER exemplifies cinema's ability to ration created within the Department of penetrate forbidden zones. This movie Film and Television at Tel-Aviv University. In make us, Israelis and Palestinians, rea- 2012, a small group of Israeli and Palesti- lize that we all yearn for a solution. nian filmmakers directed a feature film with total artistic freedom, exploring a strongly unifying subject: WATER. Yael Perlov Project initiator and Artistic Director Tel Aviv University WATER is a poetic and pastoral subject, but one that is also very political as well as violent in the context of the Israel-Palestine conflict. WATER belongs to two conflicting popula- tions, who seldom manage to overcome prejudice and political intimidation, but have found a platform for a unique colla- boration, in the form of this feature film. STILL WATERS - By an ancient spring near Jerusalem, an Israeli couple finds a quiet moment away from the rat race of Tel Aviv life. The cool water spring is also used by a group of Palestinians heading to their jobs in Israel. At high noon, they are forced to look each other in the eye. -

Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: the Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films ot Facilitate Dialogue Elana Shefrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Shefrin, Elana, "Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-MEDIATING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: THE USE OF FILMS TO FACILITATE DIALOGUE by ELANA SHEFRIN Under the Direction of M. Lane Bruner ABSTRACT With the objective of outlining a decision-making process for the selection, evaluation, and application of films for invigorating Palestinian-Israeli dialogue encounters, this project researches, collates, and weaves together the historico-political narratives of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the artistic worldviews of the Israeli and Palestinian national cinemas, and the procedural designs of successful Track II dialogue interventions. Using a tailored version of Lucien Goldman’s method of homologic textual analysis, three Palestinian and three Israeli popular film texts are analyzed along the dimensions of Historico-Political Contextuality, Socio- Cultural Intertextuality, and Ethno-National Textuality. Then, applying the six “best practices” criteria gleaned from thriving dialogue programs, coupled with the six “cautionary tales” criteria gleaned from flawed dialogue models, three bi-national peacebuilding film texts are homologically analyzed and contrasted with the six popular film texts. -

'Carole Zabar's Other Israel Festival,'

Dina Iordanova, ‘Carole Zabar’s Other Israel Festival,’ In: Film Festival Yearbook 6: Film Festivals and the Middle East. St Andrews: St Andrews Film Studies. 2014, 235-247. Carole Zabar’s Other Israel Film Festival Dina Iordanova First held in 2007, the Other Israel Film Festival (www.otherisrael.org) abides by a Mission Statement, according to which it uses film to foster social awareness and cultural understanding. The Festival presents dramatic and documentary films, as well as engaging panels about history, culture and identity on the topic of minority populations in Israel with a focus on Arab / Palestinian citizens of Israel. Our goal is to provide a dynamic and inclusive forum for exploitation of, and dialogue about, diverse communities in Israel, and encourage cinematic expression and creativity dealing with these themes. (Other Israel) In addition to Israel’s Muslim and Christian Arab populations (close to 2 million people), the festival is concerned with the cinematic treatment of other Israeli minorities. There are Druze, Bedouins, as well as the significant population of foreign workers (nearly half a million) and other non-Jewish immigrants whose experiences constitute an important yet lesser-known part of the country’s multicultural context. Initiated and largely funded by Carole Zabar (of Zabar’s, the famous Upper West Side food emporium; http://www.zabars.com), the Other Israel takes place over a week in mid- November and is headquartered at the Jewish Community Centre (JCC) in Manhattan. For a festival that is still in its first decade, it has generated an encouraging amount of media 1 attention, with articles in The Washington Post, The New York Times and the Village Voice, among other publications.1 In June 2013, I travelled to New York for a meeting with the festival’s team. -

Westminsterresearch

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Palestinian filmmaking in Israel : negotiating conflicting discourses Yael Friedman School of Media, Arts and Design This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2010. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel: Negotiating Conflicting Discourses Yael Friedman PhD 2010 Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel: Negotiating Conflicting Discourses Yael Friedman A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Acknowledgments The successful completion of this research was assisted by many I would like to thank. First, my thanks and appreciation to all the filmmakers and media professionals interviewed during this research. Without the generosity with which many shared their thoughts and experiences this research would have not been possible. -

Brochure Autumn 2018

CINEMA FOR ALL South West Wajib Cert 15 Palestine 2017 96 mins Crew Director / Annemarie Jacir Screenplay Cinematography Antoine Héberlé Film Editing Jacques Comets Cast Mohammad Bakri Abu Shadi Saleh Bakri Shadi Tarik Kopty Abu Murad Review Maria Zreik Amal Rada Alamuddin Fadya …Wajib may translate as duty, but what does that really mean? A duty to return to your homeland, like Shadi, or Abu Shadi's commitment to Synopsis the traditions associated with a wedding even if it means inviting an Israeli who has spent his life informing? What about the duty of Shadi's Nazareth, the present. Shadi has returned ex-wife to attend even though she is now living in another country with home from Italy for the wedding of his sister a different man? Or Shadi's duty to offer himself as a potential partner Amal, and is nowSynopsis accomanying his father to the folks back home even though he has a girlfriend in Italy? Abu, as they drive around town in Abu's All these questions are gently explored by Jacir, mixing with universal battered old Volvo, hand-delivering the wedding invitiations, as is required by family frustrations that will be familiar to most people who've left custom. home, even if they haven't gone far. She maintains a light touch, filling the various visits with nicely worked comic moments - including a Between visits to relatives and old family friends, they bicker and reminisce, recalcitrant parrot - and decent emotional heft, such as when the two manipulate and needle each other, men help Amal pick out her dress. -

WAJIB فيلم ل أن ماري جاسر| Ein Film Von Annemarie Jacir

واجب | WAJIB فيلم ل أن ماري جاسر| ein Film von Annemarie Jacir الملخص | Inhalt Architekt Shadi ist nicht gerade begeistert, dass er nach Jahren in Rom wieder in seine Heimatstadt Nazareth zurückkehren muss – die palästinensische Tradition jedoch zwingt ihn dazu. Seine Schwester Amal wird heiraten und Shadi muss mit seinem Vater die Einladungen persönlich übergeben. Abu Shadi, ein geschiedener Lehrer Mitte sechzig, wird nach der Hochzeit allein leben. Gemeinsam fahren die beiden Männer durch die Straßen Nazareths und stellen fest: Ihre grundverschiedenen Lebensweisen sorgen für größere Spannungen als gedacht. Wajib bedeutet soziale Verpflichtung. Derer gibt es im Film viele, mitsamt den daraus entstehenden Lügen und Verstrickungen. يعود شادي إلى بلدته بطلب من أبيه لكي يساعده في توصيل دعوات زفاف أخته، برغم أ ّنه قد رحل عن هذا المكان بإرادته منذ مدة طويلة وﻻ يُكنّ لهذه البلدة شوقا كبيرا . إﻻ أن هذا ﻻ يمنع أبا شادي من أن يحاول أن يجد سبيل إلى قلب ابنه وهما يجوبان بلدة الناصرة معا في السيارة. يسرد لنا "واجب" قص ة تدور أحداثها في إطا ر فكاهي جاف على مدار يو م واحد، محورها رجلن يطوفان المنازل في رحلة ترسم معالم علقة جديدة ، و ُتعيد إلى السطح أثقال الماضي الكادر والطاقم | Stabangaben Spielfilm, Annemarie Jacir, Palästina/FR/D/CO/NO/QA/VAE 2017, 96 min, DCP 5.1, Arabisch mit deutschen Untertiteln Regie Annemarie Jacir | Drehbuch Annemarie Jacir | Produzent Ossama Bawardi | Musik Koo Abu Ali | Kamera Antoine Héberlé | Set Design Nael Kanj | Schnitt Jacques Comets | Produktion Philistine Films in Koproduktion mit Ape&Bjørn; Ciudad Lunar Producciones; -

Annual March 27 – April 7, 2019

NJJFF sponsored by 19TH ANNUAL MARCH 27 – APRIL 7, 2019 TICKET INFORMATION SEATING POLICY FESTIVAL CO-CHAIRS Online Sponsor seating will begin 30 minutes prior to all Andrea Bergman, Joni Cohen jccmetrowest.org/njjff screenings. General admission ticket holders will Your printed receipt will serve as your ticket. be admitted 20 minutes prior to all screenings. In FESTIVAL CURATOR the event of a sell-out, a waiting list will be created. In Person Vicky Jacobs Visit the Box Office in the Gaelen Lobby, adjacent GENERAL INFORMATION to the Maurice Levin Theater on the first floor FESTIVAL COMMITTEE Films are not rated. Parental discretion is strongly of JCC MetroWest, Mondays and Thursdays, advised. Films designated “Adult Content” may Carol Churgin Abby Meth Kanter February 25–March 25, 10:00am–12:00pm. contain sexual content, explicit language and/ Myrna Comerchero Deborah Prinz Boxofficetickets.com fees apply. or violence. The NJJFF is not responsible for lost Michele Dreiblatt Ruth Ross or stolen tickets. Sorry, no refunds or exchanges. Nancy Fisher Evelyn Rothfeld Ticket Prices Festival programs are subject to change/ Robin Florin Sue Z Rudd General Seating: $13 cancellation without prior notice. For film trailers Caren Ford Sara-Ann Sanders Student, Senior, Matinee (before 5:00pm): $11 and the most up-to-date information about festival Herbert Ford Rickey Slezak At the Door events, visit our website or call the Film Festival Terri Friedman Dorit Tabak hotline at 973-530-3417. Tickets may be purchased at the theater venue Max Kleinman Neimah Tractenberg starting 45 minutes prior to screening, ALL FOREIGN FILMS HAVE ENGLISH SUBTITLES. -

A Film by ANNEMARIE JACIR Abu Shadi Is a Divorced Father and a School Teacher in His Mid-60S Living in Nazareth

PHILISTINE FILMS PRESENTS Festival du film de Locarno COMPETITION MOHAMMAD BAKRI SALEH BAKRI a film by ANNEMARIE JACIR Abu Shadi is a divorced father and a school teacher in his mid-60s living in Nazareth. After his daughter’s wedding in one month he will be living alone. Shadi, his architect son, arrives from Rome after years abroad to help his father in hand delivering the wedding invitations to each guest as per local Palestinian custom. As the estranged pair spend the day together, the tense details of their relationship come to a head challenging their fragile and very different lives. In Palestine, there is a tradition which remains a big part of life today. When someone gets married, the men of the family, usually the father and sons, are expected to personally deliver the wedding invitations to each invitee in person. There is no mailing of invitations, or having them delivered by strangers. And unless the invitations are personally delivered, it is considered disrespectful. I don’t know any other place which adheres to this tradition as much as the Palestinians living in the North of Palestine, where «Wajib» is set. «Wajib» loosely means «social duty». When my husband sister’s got married, it was his wajib to deliver the invitations with his father. I decided to silently tag along as he and his father spent five days traversing the city and surrounding villages delivering each invitation. As the silent observer, it was at times funny and other times painful. Aspects of that special relationship between father and son, the tensions of a sometimes tested love between them, came out in small ways. -

(ANSO) Screening the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Department of Anthropology and Sociology PROFESSOR (ANSO) Academic year 2019-2020 Riccardo Bocco [email protected] Screening the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Office hours Competing and Complementary Narratives through Cinematic Representations ASSISTANT ANSO096- Autumn - 6 ECTS Marie De Lutz [email protected] Schedule & Room Office hours Course Description A consistent body of knowledge about the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been produced by several social science disciplines. However, to date, few attempts have been made to combine that knowledge with the narratives produced on the conflict by films, both fictions and documentaries. Audio-visual materials related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are ‘constructions’ and interpretations of ‘realities’ at different levels, and constitute an important (memory and documentary) archive which can complement and accompany the work of research in human and social sciences. This seminar will therefore aim at examining, in a socio-political and historical perspective, the role of film directors –Israeli and Palestinian in particular- as artists and social actors, who contribute to (re)shape national and local narratives, in supporting or challenging official histories and collective memories. A selection of films produced over a time span of 15 years will be studied: from those related to the Second Intifada (2000-2005) and its immediate aftermath, to those covering the ongoing conflict during the past decade. Interestingly, the Israeli and Palestinian cinematic narratives produced during these two periods show important aspects of convergence and complementarity in addressing peace and conflict dynamics in both societies. And gendering the approaches of film directors to the chosen movies’ topics will be part and parcel of the overall endeavour. -

At the Movies: ‘Omar’ Vs

At the Movies: ‘Omar’ vs. ‘Bethlehem’ This year’s Israeli nominee for the Academy Award, “Bethlehem,” was remarkably similar thematically to the Palestinian entry, “Omar.” Both depict the relationship of an Israeli security handler with a young Palestinian informant in the West Bank. The plot lines diverge significantly, but then converge in a similarly brutal climax. The Israeli film focuses almost equally on the Israeli and Palestinian characters, and depicts the Israeli Shin Bet officer as developing a fatherly affection for his Palestinian source, despite the fundamentally exploitative nature of their interactions. Sanfur, the Palestinian teen, is also emotionally affected by this relationship, but forced into a shattering atonement for being a traitor. Similarly, Omar, the Palestinian young man in the eponymous film, is left feeling bereft, in a dead-end situation. It’s not entirely clear if Omar is playing a double game, and who else may be betraying whom; this poisons his courtship with his love Nadia, who may not be entirely innocent herself. The director of “Omar,” Hany Abu-Assad, is very talented. I remember being impressed by “Paradise Now,” his earlier film on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, also shortlisted for an Oscar. Neither film wound up winning the prize, but “Omar” represents the political progress gained by the Palestinians in the intervening years, by being nominated in the Best Foreign Language category as the entry of “Palestine,” rather than “the Palestinian territories.” It turns out, however, that Abu-Assad was born in Israel. The film’s publicity erroneously refers to his birthplace and hometown, Nazareth, as being in Palestine and not in Israel; and he is said to refuse to speak Hebrew in public. -

Resource List to Help Understand the Palestinian Struggle Summer 2021

Resource List to Help Understand the Palestinian Struggle Summer 2021 This is a long list: however, titles in red offer suggested starting places. The list was compiled in May 2021 by Maureen McPherson, a member of St. Martin’s United Church in Saskatoon. Go to the end of the list to find some ways you can support Palestinian farmers and craftspeople by buying their products. The following online material offers a good way to start: • A good way to begin any study is with a short video called Israel and Palestine: A Very Short Introduction (6 min 27 sec.) 2013. Produced by Jewish Voice for Peace. Israel- Palestinian conflict VERY briefly explained in this animated, historically accurate video. Highly recommended as an introduction to the whole issue This is a short video that would work well during a church service. Would work well to spark discussion in a Youth Group or other gathering, especially combined with Keith Simmonds presentation. Available on YouTube. • For an up-to-date look at the conflict from a United Church perspective, watch the presentation by Keith Simmonds, minister of Duncan United Church in Duncan BC, who served as an Ecumenical Accompanier in Palestine from Dec. 27, 2019 to March 10, 2020. (about 15 min.) Under the auspices of the World Council of Churches, Ecumenical Accompaniers from a variety of countries and faith backgrounds spend time in Palestine and Israel to serve as the eyes and ears of the world. The talk was given to the Pacific Mountain Regional Meeting of the United Church in Oct. -

Permission to Perform: Palestinian Theatre in Jerusalem (1967-1993)

Permission To Perform: Palestinian Theatre in Jerusalem (1967-1993) Samer Al-Saber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Thomas E. Postlewait, Chair Sarah Bryant-Bertail Daniel Chirot Terri Lynn Deyoung Michael Vincente Perez Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Drama University of Washington Abstract Permission To Perform: Palestinian Theatre in Jerusalem (1967-1993) Samer Al-Saber Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Thomas E. Postlewait School of Drama In the period of 1967 to 1993, Palestinian theatre became a major platform for the expression of the Palestinian identity. This dissertation asks the following question: Why and how did Palestinian theatre thrive in Jerusalem during this period? I begin this study by outlining all the laws and regulations that influenced the development of Palestinian theatre practices since the Ottoman period. Then I focus on the practices and aesthetics of the theatre troupes which successfully established theatre buildings in Jerusalem. In surveying both the state-imposed laws and the grassroots theatrical practices, I document examples of the interactions between the theatre artists and the Israeli authorities. Since Palestinian theatre artists had to apply for the permission to perform from the civilian censorship council in West Jerusalem and the military governors of various regions in the Occupied territories, the Palestinians developed various strategies and tactics in order to assert their identity and maintain their livelihood under occupation. By documenting examples of Palestinian theatre in ! ""! Jerusalem, I argue that the permission to perform shaped the way theatre flourished and eventually declined in the city.