At the Movies: ‘Omar’ Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

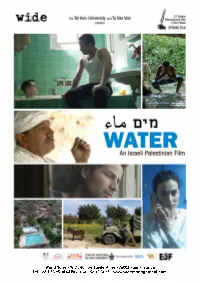

WATER-Presskit-06.09.2012.Pdf

World Sales - WIDE 40, rue Sainte Anne - 75002 Paris - France Tel. +33 1 53 95 04 64 Fax: +33 1 53 95 04 65 - www.widemanagement.com water pages corrigées_water 14/08/12 14:33 Page2 A FEATURE FILM BORN OUT OF A UNIQUE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN COOPERATION THE FILM HD, 120 minutes, color, original version : Arabic, Hebrew, English Produced by the Film and Television department of the Tel Aviv University In association with Tu Vas Voir. The project WATER is a cinematic coope- WATER exemplifies cinema's ability to ration created within the Department of penetrate forbidden zones. This movie Film and Television at Tel-Aviv University. In make us, Israelis and Palestinians, rea- 2012, a small group of Israeli and Palesti- lize that we all yearn for a solution. nian filmmakers directed a feature film with total artistic freedom, exploring a strongly unifying subject: WATER. Yael Perlov Project initiator and Artistic Director Tel Aviv University WATER is a poetic and pastoral subject, but one that is also very political as well as violent in the context of the Israel-Palestine conflict. WATER belongs to two conflicting popula- tions, who seldom manage to overcome prejudice and political intimidation, but have found a platform for a unique colla- boration, in the form of this feature film. STILL WATERS - By an ancient spring near Jerusalem, an Israeli couple finds a quiet moment away from the rat race of Tel Aviv life. The cool water spring is also used by a group of Palestinians heading to their jobs in Israel. At high noon, they are forced to look each other in the eye. -

Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: the Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films ot Facilitate Dialogue Elana Shefrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Shefrin, Elana, "Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-MEDIATING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: THE USE OF FILMS TO FACILITATE DIALOGUE by ELANA SHEFRIN Under the Direction of M. Lane Bruner ABSTRACT With the objective of outlining a decision-making process for the selection, evaluation, and application of films for invigorating Palestinian-Israeli dialogue encounters, this project researches, collates, and weaves together the historico-political narratives of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the artistic worldviews of the Israeli and Palestinian national cinemas, and the procedural designs of successful Track II dialogue interventions. Using a tailored version of Lucien Goldman’s method of homologic textual analysis, three Palestinian and three Israeli popular film texts are analyzed along the dimensions of Historico-Political Contextuality, Socio- Cultural Intertextuality, and Ethno-National Textuality. Then, applying the six “best practices” criteria gleaned from thriving dialogue programs, coupled with the six “cautionary tales” criteria gleaned from flawed dialogue models, three bi-national peacebuilding film texts are homologically analyzed and contrasted with the six popular film texts. -

'Carole Zabar's Other Israel Festival,'

Dina Iordanova, ‘Carole Zabar’s Other Israel Festival,’ In: Film Festival Yearbook 6: Film Festivals and the Middle East. St Andrews: St Andrews Film Studies. 2014, 235-247. Carole Zabar’s Other Israel Film Festival Dina Iordanova First held in 2007, the Other Israel Film Festival (www.otherisrael.org) abides by a Mission Statement, according to which it uses film to foster social awareness and cultural understanding. The Festival presents dramatic and documentary films, as well as engaging panels about history, culture and identity on the topic of minority populations in Israel with a focus on Arab / Palestinian citizens of Israel. Our goal is to provide a dynamic and inclusive forum for exploitation of, and dialogue about, diverse communities in Israel, and encourage cinematic expression and creativity dealing with these themes. (Other Israel) In addition to Israel’s Muslim and Christian Arab populations (close to 2 million people), the festival is concerned with the cinematic treatment of other Israeli minorities. There are Druze, Bedouins, as well as the significant population of foreign workers (nearly half a million) and other non-Jewish immigrants whose experiences constitute an important yet lesser-known part of the country’s multicultural context. Initiated and largely funded by Carole Zabar (of Zabar’s, the famous Upper West Side food emporium; http://www.zabars.com), the Other Israel takes place over a week in mid- November and is headquartered at the Jewish Community Centre (JCC) in Manhattan. For a festival that is still in its first decade, it has generated an encouraging amount of media 1 attention, with articles in The Washington Post, The New York Times and the Village Voice, among other publications.1 In June 2013, I travelled to New York for a meeting with the festival’s team. -

Hany Abu-Assad's Historical Testimonies

Hany Abu-Assad’s Historical Testimonies History and Identity in Palestinian Cinema of the Everyday Teuntje Schrijver 5819334 Keizersgracht 637B 1017DS Amsterdam 06-52559976 [email protected] Dr. A.M. Geil MA Film Studies University of Amsterdam 0 1 University of Amsterdam 2 Table of Content Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Rana’s Wedding ........................................................................................................ 10 Journey .................................................................................................................. 14 Control ............................................................ Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Witnessing ...................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. 2. Paradise Now .................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Journey ........................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Media technology ........................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Witnessing ...................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. 3. Omar .................................................................. Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Historical narrative ......................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Knowledge ..................................................... -

Annemarie Jacir

WAJIB (The Wedding Invitation) A film by Annemarie Jacir 96 mins / Palestine/France/Germany/Columbia/Norway/Qatar 2017/ in Arabic with English subtitles / cert tbc London Film Festival 2017 Competition - Special Mention Release September 14th 2018 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel. 07940 584066 / 07825 603705 / [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – [email protected] or Dena Blakeman – [email protected] 79-80 Margaret Street London W1W 8TA Tel: 020 7299 3685 [email protected] www.newwavefilms.co.uk SYNOPSIS Abu Shadi (Mohammad Bakri) is a divorced father and a school teacher in his mid-60s living in Nazareth, (the largest Arab majority city in Israel). He is separated from his wife who lives in the US, so after his daughter’s wedding in one month he will be living alone. Shadi (played by Mohammad Bakri’s real-life son Saleh Bakri), his architect son, arrives from Rome after years abroad to help his father in hand-delivering the wedding invitations to each guest, as is the local Palestinian custom. (The term wajib roughly translates as social duty.) As the estranged pair spend the day together travelling all over the city visiting relatives, friends and people Abu Shadi is obligated to invite, the details of their relationship come to a head, challenging the preconceptions of their very different lives. JURY Prize Oran,2018 BEST ACTOR for Mohammed Bakri and Saleh Bakri, Oran, 2018 BEST FILM, Kosovo 2018 BEST FILM, Casablanca 2018 And many other international awards for the film and the actors It was also Palestine’s entry for the 2018 Oscars. -

Westminsterresearch

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Palestinian filmmaking in Israel : negotiating conflicting discourses Yael Friedman School of Media, Arts and Design This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2010. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel: Negotiating Conflicting Discourses Yael Friedman PhD 2010 Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel: Negotiating Conflicting Discourses Yael Friedman A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Acknowledgments The successful completion of this research was assisted by many I would like to thank. First, my thanks and appreciation to all the filmmakers and media professionals interviewed during this research. Without the generosity with which many shared their thoughts and experiences this research would have not been possible. -

Brochure Autumn 2018

CINEMA FOR ALL South West Wajib Cert 15 Palestine 2017 96 mins Crew Director / Annemarie Jacir Screenplay Cinematography Antoine Héberlé Film Editing Jacques Comets Cast Mohammad Bakri Abu Shadi Saleh Bakri Shadi Tarik Kopty Abu Murad Review Maria Zreik Amal Rada Alamuddin Fadya …Wajib may translate as duty, but what does that really mean? A duty to return to your homeland, like Shadi, or Abu Shadi's commitment to Synopsis the traditions associated with a wedding even if it means inviting an Israeli who has spent his life informing? What about the duty of Shadi's Nazareth, the present. Shadi has returned ex-wife to attend even though she is now living in another country with home from Italy for the wedding of his sister a different man? Or Shadi's duty to offer himself as a potential partner Amal, and is nowSynopsis accomanying his father to the folks back home even though he has a girlfriend in Italy? Abu, as they drive around town in Abu's All these questions are gently explored by Jacir, mixing with universal battered old Volvo, hand-delivering the wedding invitiations, as is required by family frustrations that will be familiar to most people who've left custom. home, even if they haven't gone far. She maintains a light touch, filling the various visits with nicely worked comic moments - including a Between visits to relatives and old family friends, they bicker and reminisce, recalcitrant parrot - and decent emotional heft, such as when the two manipulate and needle each other, men help Amal pick out her dress. -

Festival-Ubrzaj-Me-Katalog 2014.Pdf

Festival filma o ljudskim pravima / Fast Forward Human Rights Film Festival Organizator / Organizer: Centar za građansko obrazovanje (CGO) / Centre for Civic Education (CCE) Savjet Festivala filma o ljudskim pravima UBRZAJ / FAST FORWARD Human Rights Film Festival Council: Balša Brković, pisac i urednik “Arta“ u dnevniku “Vijesti“ / writer and editor of „Art“ in daily „Vijesti“ Branko Baletić, reditelj i direktor Crnogorske kinoteke / director and CEO of Montenegrin Film Archive Daliborka Uljarević, izvršna direktorka CGO-a / CCE Executive director Dušan Vuleković, reditelj / director Janko Ljumović, direktor Crnogorskog narodnog pozorišta i profesor na Fakultetu dramskih umjetnosti Univerziteta Crne Gore / CEO of Montenegrin National Theatre and professor at the Faculty of Drama Arts of the University of Montenegro Miodrag Popović, urednik filmskog programa u KIC “Budo Tomović“ / editor of the Film programme at KIC “Budo Tomović” Mladen Vušurović, direktor Međunarodnog festivala dokumentarnog filma “Beldocs“ / CEO of the International Documentary Film Festival “Beldocs” Tanja Šuković, urednica dokumentarnog programa u RTCG / Documentary Programme editor at RTCG Stručni saradnici / Expert Associates: Dragana Koprivica Jelena Popović Miloš Knežević Mira Popović Nikola Đonović Ognjen Gazivoda Paula Petričević Svetlana Pešić Tamara Milaš Wanda Tiefenbacher Prevod i lektura filmova / Translation and proofreading of films: Beldocs i Centar za građansko obrazovanje (CGO) / Beldocs and Centre for Civic Education (CCE) Dizajn i produkcija / Design -

A Film by Hany Abu-Assad

Mongrel Media Presents Omar A film by Hany Abu-Assad Winner Jury Prize Un Certain Regard Cannes Film Festival Official Selection Toronto International Film Festival Official Selection New York Film Festival Running Time: 98 minutes Color Language: Arabic/Hebrew w/ English subtitles Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com SYNOPSIS Omar is accustomed to dodging surveillance bullets to cross the separation wall to visit his secret love Nadia. But occupied Palestine knows neither simple love nor clear-cut war. On the other side of the wall, the sensitive young baker Omar becomes a freedom fighter who must face painful choices about life and manhood. When Omar is captured after a deadly act of resistance, he falls into a cat-and-mouse game with the military police. Suspicion and betrayal jeopardize his longtime trust with accomplices and childhood friends Amjad and Tarek, Nadia’s militant brother. Omar’s feelings quickly become as torn apart as the Palestinian landscape. But it’s soon evident that everything he does is for his love of Nadia. CAST Adam Bakri Omar Leem Lubany Nadia Waleed F. Zuaiter Agent Rami Samer Bisharat Amjad Eyad Hourani Tarek (In Order of Appearance) Mousa Habib Allah Sewing Shop Manager Doraid Liddawi Soldier Adi Krayim Soldier #1 Foad Abed-Eihadi Soldier #2 Essam Abu Aabed Omar’s Boss Anna Maria Hawa Omar’s Sister -

17 Noviembre 2018 Jazz Cinema Cine Palestino

13 – 17 NOVIEMBRE 2018 JAZZ CINEMA CINE PALESTINO MARTES 13 20 h.: JAZZ CINEMA (1) Anatomy of a Murder / Anatomía de un asesinato, Otto Preminger, 1959. Int.: James Stewart, Lee Remick, Ben Gazzara. USA. VOSE. 160 min. Presentación y coloquio: Roberto Sánchez. MIÉRCOLES 14 18 h.: CINE PALESTINO (3): 20 h.: CINE PALESTINO (3): 22 h.: JAZZ CINEMA (2): The Wanted 18, The Wanted 18, Tete Montoliu, una mirada, Amer Shomali, Paul Cowan, 2014. Amer Shomali, Paul Cowan, 2014. Pere Pons, 2007. Documental Animación. Documental Animación. Documental. España. VOSE. 64 min. B-R. Canadá. VOSE. 75 min. B-R. Canadá. VOSE. 75 min. B-R. Presentación y coloquio: Roberto Sánchez. Presentación: Miguel Ángel Encuentra. JUEVES 15 18 h.: CINE PALESTINO (4): 20 h.: CINE PALESTINO (4): Wajib / Invitación de boda, Annemarie Jacir, 2017 Wajib / Invitación de boda, Annemarie Jacir, 2017 Int.: Mohammad Bakri, Saleh Bakri, Maria Zreik Int.: Mohammad Bakri, Saleh Bakri, Maria Zreik Palestina-Francia. VOSE. 96 min. B-R. Palestina-Francia. VOSE. 96 min. B-R. Presentación: Ángel Gonzalvo Vallespí. VIERNES 16 18 h.: CINE PALESTINO (5): 20 h.: CINE PALESTINO (5): Omar, Hany Abu-Assad,2013. Omar, Hany Abu-Assad,2013. Int.: Adam Bakri, Samer Bishara, Eyad Hourani. Int.: Adam Bakri, Samer Bishara, Eyad Hourani. Palestina. VOSE. 96 min. 35 mm. Palestina. VOSE. 96 min. 35 mm. Presentación: Luis Felipe Alegre. SÁBADO 17 19 h.: CINE PALESTINO (y 6) 3000 Layla / 3000 noches, Mai Masri, 2015. Int.: Maisa Abd Elhadj, Hussein Nakhleh, Abeer Zeibbak Haddad. Jordania-Palestina-Francia-Libano. VOSE. 103 min. B-R. Presentación en vídeo de la directora Mai Masri. -

Filmprogramm Februar 2018 Kino Als Selbstbehauptung: Filme Aus

Filmprogramm Februar 2018 Kino als Selbstbehauptung: Filme aus Palästina →4 Re-Edition →11 Premieren: Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami / Favela Olímpica →13 Ex Libris: The New York Public Library / Mobile Homes →15 Agenda →16/17 02 Anna Huber: Fingerdances →18 Filmgeschichte / Festivalfilme →19 Special: Flucht →20 Berner Premiere →21 18 Rex Kids →22 / Uncut / Rex Tone →23 8. sonOhr Radio & Podcast Festival→24 www.rexbern.ch DIE ZELLE Editorial Von Thomas Allenbach «Kino als Selbstbehauptung»: Unter diesen Titel stellt Irit Neidhardt ihren Text zu unserem Februar-Schwerpunkt mit Spielfilmen palästinensischer Filmschaffender. Tatsächlich sind diese Filme auch Instrumente im kultu- rellen Kampf um die Behauptung der eigenen Identität: Indem sie paläs- tinensisches Leben reflektieren, machen oder halten sie sichtbar, was zu verschwinden droht. Doch sie erschöpfen sich nicht darin, sondern gewin- nen künstlerisch Freiheit gerade dadurch, dass sie auch Konflikte und Wider- sprüche innerhalb der palästinensischen Gesellschaft aufgreifen. Das zeigt sich bereits in Michel KhleifisHochzeit in Galiläa aus dem Jahr 1987, mit FLUCHT dem wir die Reihe eröffnen, und wird noch deutlicher in Annemarie Jacirs neuem Film Wajib, mit dem wir – in Anwesenheit der Regisseurin – den 25.01. – 16.09.2018 Zyklus beschliessen. In dieser Programmreihe KUNSTHALLE BERN Wir zeigen Filme von Regisseurinnen und Regisseuren, die sich bewusst präsentieren wir Live-Kino- 24. Februar – 6. Mai 2018 der Politik der Eskalation widersetzen, auf welche die Hardliner auf beiden events der dritten Art. John Armleder, Bianca Baldi, Cosima von Bonin, Seiten des ausweglos scheinenden Konflikts setzen. Sie geraten damit oft Manuel Burgener, Tom Burr, Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Beat Feller, Beat Frank, Anita Leisz, Annina Matter / Urs Zahn, zwischen alle Fronten, wie etwa Hany Abu-Assad, dessen Paradise Now Donnerstag, 15.2. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 92Nd Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 92ND ACADEMY AWARDS FILM TITLE ACTORS ACTRESSES ABOMINABLE Albert Tsai Chloe Bennet Tenzing Norgay Trainor Sarah Paulson Joseph Izzo Tsai Chin Eddie Izzard AD ASTRA Brad Pitt Ruth Negga Tommy Lee Jones Liv Tyler John Ortiz Kimberly Elise Donald Sutherland LisaGay Hamilton Greg Bryk Loren Dean John Finn Donnie Keshawarz Bobby Nish ADAM Nicholas Alexander Bobbi Salvor Menuez Bobbi Salvor Menuez Margaret Qualley Leo Sheng THE ADDAMS FAMILY Oscar Isaac Charlize Theron Finn Wolfhard Chloe Grace Moretz Nick Kroll Bette Midler Snoop Dogg Allison Janney Martin Short Catherine O'Hara Tituss Burgess Jenifer Lewis Conrad Vernon Elsie Fisher Scott Underwood THE AERONAUTS Eddie Redmayne Felicity Jones Himesh Patel Phoebe Fox Robert Glenister Rebecca Front Vincent Perez Anne Reid Tom Courtenay Page 1 of 53 FILM TITLE ACTORS ACTRESSES AFTER THE WEDDING Billy Crudup Julianne Moore Michelle Williams Abby Quinn THE AFTERMATH Alexander Skarsgard Keira Knightley Jason Clarke Kate Phillips Martin Compston Flora Li Thiemann Jannik Schumann ÁGA Mikhail Aprosimov Feodosia Ivanova Sergey Egorov Galina Tikhonova ALADDIN Will Smith Naomi Scott Mena Massoud Marwan Kenzari Navid Negahban Nasim Pedrad Billy Magnussen Numan Acar ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL Christoph Waltz Rosa Salazar Mahershala Ali Jennifer Connelly Ed Skrein Lana Condor Jackie Earle Haley Idara Victor Keean Johnson Eiza Gonzalez Jorge Lendeborg, Jr. Jeff Fahey Rick Yune ALWAYS BE MY MAYBE Randall Park Ali Wong James Saito Michelle Buteau Daniel Dae Kim Vivian Bang Keanu Reeves Charlyne Yi Karan Soni Susan Park THE AMAZING JOHNATHAN —— —— DOCUMENTARY AMERICAN FACTORY —— —— Page 2 of 53 FILM TITLE ACTORS ACTRESSES AMERICAN WOMAN Aaron Paul Sienna Miller Will Sasso Christina Hendricks Pat Healy Sky Ferreira Alex Neustaedter Amy Madigan E.