Investigating Kuwaiti Television Serial Dramas of Ramadan: Social Issues and Narrative Forms Across Three Transformative Production Eras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Structured Observation and Content Analysis to Explore the Presence of Older People in Public Fora in Developing Countries

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Aging Research Volume 2014, Article ID 860612, 12 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/860612 Research Article Using Structured Observation and Content Analysis to Explore the Presence of Older People in Public Fora in Developing Countries Geraldine Nosowska,1 Kevin McKee,2 and Lena Dahlberg2,3 1 Effective Practice Ltd., 8 Bridgetown, Totnes, Devon TQ95AB, UK 2School of Education, Health and Social Studies, Dalarna University, 791 88 Falun, Sweden 3Aging Research Centre, Karolinska Institutet and Stockholm University, Gavlegatan¨ 16, 113 30 Stockholm, Sweden Correspondence should be addressed to Lena Dahlberg; [email protected] Received 15 September 2014; Revised 10 November 2014; Accepted 10 November 2014; Published 8 December 2014 AcademicEditor:F.R.Ferraro Copyright © 2014 Geraldine Nosowska et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. There is a lack of research on the everyday lives of older people in developing countries. This exploratory study used structured observation and content analysis to examine the presence of older people in public fora and considered the methods’ potential for understanding older people’s social integration and inclusion. Structured observation occurred of public social spaces in six cities each located in a different developing country and in one city in the United Kingdom, together with content analysis of the presence of people in newspaper pictures and on television in the selected countries. Results indicated that across all fieldwork sites and data sources, there was a low presence of older people, with women considerably less present than men in developing countries. -

Arab Filmmakers of the Middle East

Armes roy Armes is Professor Emeritus of Film “Constitutes a ‘counter-reading’ of Film and MEdia • MIddle EasT at Middlesex University. He has published received views and assumptions widely on world cinema. He is author of Arab Filmmakers Arab Filmmakers Dictionary of African Filmmakers (IUP, 2008). The fragmented history of Arab about the absence of Arab cinema Arab Filmmakers in the Middle East.” —michael T. martin, Middle Eastern cinema—with its Black Film Center/Archive, of the Indiana University powerful documentary component— reflects all too clearly the fragmented Middle East history of the Arab peoples and is in- “Esential for libraries and useful for individual readers who will deed comprehensible only when this find essays on subjects rarely treat- history is taken into account. While ed in English.” —Kevin Dwyer, neighboring countries, such as Tur- A D i c t i o n A r y American University in Cairo key, Israel, and Iran, have coherent the of national film histories which have In this landmark dictionary, Roy Armes details the scope and diversity of filmmak- been comprehensively documented, ing across the Arab Middle East. Listing Middle East Middle more than 550 feature films by more than the Arab Middle East has been given 250 filmmakers, and short and documentary comparatively little attention. films by another 900 filmmakers, this vol- ume covers the film production in Iraq, Jor- —from the introduction dan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and the Gulf States. An introduction by Armes locates film and filmmaking traditions in the region from early efforts in the silent era to state- funded productions by isolated filmmakers and politically engaged documentarians. -

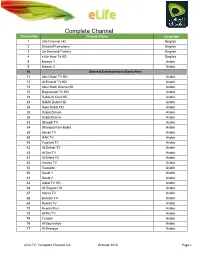

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Liste Des Canaux HD +

Liste des Canaux HD + - Enregistrement & programmation des enregistrements de chaînes (non-fonctionnel sur boîte Android / Smart Tv) - Le seul iptv offrant la fonction marche arrière sur vos canaux préférés - Vidéo sur demande – Films – Séries – Spectacle – Documentaire (Français, Anglais et Espagnole) Liste des canaux FRANÇAIS QUEBEC • TVA • TVA WEST • V TELE • TELE QUEBEC • LCN • MOI & CIE • CANAL D • RADIO CANADA • RADIO CANADA FREE • RDI • RDI FREE • CANAL SAVOIR • AMI TELE • UNIS TV • CANAL VIE • CASA • MUSIQUE PLUS • ZESTE • CANAL INVESTIGATION • CANAL D • ADDICK TV • SERIE + • Z TELE • VRAK • RDS • TVA SPORT • TVA SPORT 2 • RDS 2 • MAX • HISTORIA • PRISE 2 • SUPER ECRAN 1 • SUPER ECRAN 2 • SUPER ECRAN 3 • SUPER ECRAN 4 • ARTV • ICI EXPLORA • CINE-POP • EVASION • YOOPA • TELETOON *** AJOUT DE CANAUX A CHAQUE MOIS *** HORS QUÉBEC • France • TF1 • TFI LOCAL TIME -6 • M6 • M6 LOCAL TIME -6 • FRANCE 2 • FRANCE 3 • FRANCE 3 LOCAL TIME -6 • FRANCE 4 • FRANCE O • FRANCE 5 • ARTE • LCI • TV5 • TV5 MONDE • EURONEWS • BFM • BFM BUSINESS • FRANCE INFO • FRANCE 24 • CNEWS • HD1 • 6TER • W9 • W9 LOCAL TIME -6 • C8 • C8 LOCAL TIME -6 • 13 EIME RUE • PARIS PREMIERE • TEVA • COMEDIE • E! • NUMERO 23 • AB1 • TV BREIZH • NON STOP PEOPLE • NT1 • TCM CINEMA • TMC • CANAL + • CANAL + LOCAL TIME -6 • CANEL + CINEMA • CANAL + SERIES • CANAL + FAMILY • CANAL + DECALE • CINE + PREMIER • CINE + FRISSON • CINE + EMOTION • CINE + CLUB • CINE + CLASSIC • CINE FAMIZ • CINE FX • C STAR • CINE POLAR • OCS CITY • OCS MAX • OCS CHOC • OCS GEANT • GAME ONE • ACTION -

Westminsterresearch

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Palestinian filmmaking in Israel : negotiating conflicting discourses Yael Friedman School of Media, Arts and Design This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2010. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel: Negotiating Conflicting Discourses Yael Friedman PhD 2010 Palestinian Filmmaking in Israel: Negotiating Conflicting Discourses Yael Friedman A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Acknowledgments The successful completion of this research was assisted by many I would like to thank. First, my thanks and appreciation to all the filmmakers and media professionals interviewed during this research. Without the generosity with which many shared their thoughts and experiences this research would have not been possible. -

Liste Des Chaînes TV Chaînes En Option Haute Définition Inclus Dans Et Service Replay

Chaînes incluses 4K Ultra Haute Définition Inclus dans Liste des chaînes TV Chaînes en option Haute définition Inclus dans et Service Replay TNT 80 Comédie+ 204 Ushuaïa TV 314 France 3 Haute Normandie 0 Mosaique 81 Clique TV 205 Histoire 315 France 3 Languedoc 1 TF1 82 Toonami 206 Toute l'Histoire 316 France 3 Limousin 2 France 2 84 MTV 207 Science & Vie TV 317 France 3 Lorraine 3 France 3 86 Non Stop People 208 Animaux 318 France 3 Midi Pyrénées 4 Canal+ 87 MCM 209 Trek 319 France 3 Nord Pas de Calais 5 France 5 88 J-One 211 Souvenirs From Earth 320 France 3 Île de France 6 M6 89 Game One +1 212 Ikono TV 321 France 3 Pays de Loire 7 Arte 90 Mangas 213 Museum 322 France 3 Picardie 8 C8 91 ES1 214 MyZen Nature 323 France 3 Poitou Charente 9 W9 92 Adult Swim 215 Travel Channel 324 France 3 Provence Alpes 10 TMC 94 Gong 216 Chasse et pêche 325 France 3 Rhône-Alpes 11 TFX 95 Gong Max 217 Seasons 326 NoA 12 NRJ 12 96 Ginx 218 Télésud 13 LCP AN / Public Sénat 97 Comedy Central 219 Tahiti Nui INFOS & NEWS 14 France 4 98 Vice TV 221 Connaissances du Monde 340 France 24 (français) 15 BFM TV 99 BET 341 France 24 (anglais) 16 CNews 100 Stingray Festival 4K STYLE DE VIE / PRATIQUE 342 France 24 (arabe) 17 CStar 102 ARTE HDR (selon offre souscrite) 230 La Chaîne Météo 343 LCP Assemblée Nationale 18 Gulli 231 01 Net 344 Public Sénat 20 TF1 Séries Films CINÉMA 232 Autoplus 345 Euronews 21 L’Équipe 106 Canal + Séries 234 Gourmand TV 346 Euronews International 22 6ter 107 Abctek 235 Astro Center TV 347 BFM Business 23 RMC Story 108 Disneytek 236 Demain.TV -

State of Denial

State of Denial Jacket "INSURGENTS AND TERRORISTS RETAIN THE RESOURCES AND CAPABILITIES TO SUSTAIN AND EVEN INCREASE CURRENT LEVEL OF VIOLENCE THROUGH THE NEXT YEAR." This was the secret Pentagon assessment sent to the White House in May 2006. The forecast of a more violent 2007 in Iraq contradicted the repeated optimistic statements of President Bush, including one, two days earlier, when he said we were at a "turning point" that history would mark as the time "the forces of terror began their long retreat." State of Denial examines how the Bush administration avoided telling the truth about Iraq to the public, to Congress, and often to themselves. Two days after the May report, the Pentagon told Congress, in a report required by law, that the "appeal and motivation for continued violent action will begin to wane in early 2007." In this detailed inside story of a war-torn White House, Bob Woodward reveals how White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card, with the indirect support of other high officials, tried for 18 months to get Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld replaced. The president and Vice President Cheney refused. At the beginning of Bush's second term, Stephen Hadley, who replaced Condoleezza Rice as national security adviser, gave the administration a "D minus" on implementing its policies. A SECRET report to the new Secretary of State Rice from her counselor stated that, nearly two years after the invasion, Iraq was a "failed state." State of Denial reveals that at the urging of Vice President Cheney and Rumsfeld, the most frequent outside visitor and Iraq adviser to President Bush is former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who, haunted still by the loss in Vietnam, emerges as a hidden and potent voice. -

Kuwaittimes 25-6-2019 .Qxp Layout 1

SHAWWAL 22, 1440 AH TUESDAY, JUNE 25, 2019 28 Pages Max 50º Min 30º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17865 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net US ambassador meets Kuwaiti Searing heat across Europe Bitcoin surges above $11,000 Martinez, Aguero goals send 5 grads planning to study in US 6 sparks scramble for shade 11 thanks to Facebook currency 26 Argentina into Copa quarters Assembly urges Kuwait govt to boycott Bahrain workshop Israel calls on Palestinians to ‘surrender’ • US eyes Israel-Gulf rapprochement By B Izzak and Agencies development institutions were flying to the tiny kingdom, which in a rarity is openly welcoming Israelis, who have KUWAIT: The National Assembly yesterday strongly forged an indirect alliance with Gulf rulers due to mutual lashed out at a US-led workshop in Bahrain to push hostility with Iran. stalled Middle East peace and called on the Kuwaiti Led by US President Donald Trump’s son-in-law and government to boycott the two-day conference starting adviser Jared Kushner, the Peace to Prosperity economic today. In a statement passed unanimously, the Assembly workshop that begins today evening is billed as the start said the conference, which is being attended by several of a new approach that will later include political solu- Arab countries and boycotted by the Palestinians, aims tions to the long intractable Middle East conflict. It pro- at normalizing ties with Israel at the expense of poses raising more than $50 billion in fresh investment Palestinian rights. for the Palestinians and their Arab neighbors with major The statement expressed total rejection of the confer- projects to boost infrastructure, education, tourism and ence’s outcome, which undermines legitimate and histor- cross-border trade. -

Acls Fellowships 2009 Fellows and Grantees Of

2 0 0 9 FELLOWS AND GRANTEES O F T H E A M E R I C A N C O U N C I L O F L E A R N E D S ocieties Funded by the ACLS ACLS FELLOWSHIPS Fellowship Endowment Glaire Dempsey Anderson, Assistant Professor, Art History, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill The Munyas of Córdoba: Suburban Villas and the Court Elite in Umayyad al-Andalus Zayde Antrim, Assistant Professor, History and International Studies, Trinity College (CT) Routes and Realms: The Power of Place in the Early Islamic World Robin B. Barnes, Professor, History, Davidson College Astrology and Reformation Gina Bloom, Assistant Professor, English Literature, University of California, Davis Games and Manhood in the Early Modern Theater Mark Evan Bonds, Professor, Music, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill The Myth of Absolute Music Theresa Braunschneider, Associate Professor, English, Washington and Lee University After Dark: Modern Nighttime in Eighteenth-Century British Literature Palmira Brummett, Professor, Middle Eastern History, University of Tennessee, Knoxville The Ottoman Adriatic, c. 1500–1700 Michael C. Carhart, Assistant Professor, History, Old Dominion University The Caucasians: Central Asia in the European Imagination Caroline F. Castiglione, Associate Professor, Italian Studies and History, Brown University Accounting for Affection: Mothering and Politics in Rome, 1630–1730 James Andrew Cowell, Professor, Linguistics and French, University of Colorado, Boulder Documenting Arapaho Linguistic Culture Laura Doyle, Professor, English Literature, University of Massachusetts, Amherst Untold Returns: A Postcolonial Literary History of Modernism Susana Draper, Assistant Professor, Latin American Studies, Princeton University The Prison, the Mall, and the Archive: Space, Literature, and Visual Arts in Post-Dictatorship Culture Caryl G. -

DIGITAL CHANNEL LINEUP Fort Pierce

West Palm Beach/ DIGITAL CHANNEL LINEUP Fort Pierce Digital Access 95 A&E 39 Golf Channel 281 Turner Classic Movies 1562 Rock 494 HDNET Movies 13/425 ABC 25 WPBF (HD) 394 Grit TV WAMI 70 TV Land 1564 Rock Alternative 1002 HES HD 27 AccuWeather 74 HGTV 9 UniMas 1566 Rock en Español 461 HGTV HD 239 Alive TV 60 History 5/415 Univision 23 WLTV (HD) 1589 Romance Latino 489 History HD 21 America TeVe 50 HLN 275 Upliftv 1593 Smooth Jazz 466 HLN HD 61 Animal Planet 212 HSN 82 USA Network 1559 Soul Storm 482 Infotainment HD 399 Azteca America 18 ION 67 WPXP 90 VH1 1596 Swinging Standards 556 Investigation Discovery HD 51 BBC America 231 Infotainment 634 Vme TV 1595 The Blues 504 Lifetime HD 397 Becon 63 WBEC 111 Investigation Discovery 103 WE TV 1570 The Chill Lounge 505 Lifetime Movie Network HD 85 BET 26 Lifetime 11 WeatherNation WPEC 1584 The Light 485 Liquidation Channel HD 395 Boca TV 101 Lifetime Movie Network Music Channels 1592 The Spa 1003 MedicosTV HD 392 Bounce WAMI 213 Liquidation Channel 1565 Adult Alternative 1585 Today’s Latin Pop 474 MSNBC HD 77 Bravo 401 Me-TV WPTV 1581 Alt Country/Americana 1555 Urban Beats 434 MTV HD 301 Cartoon Network 53 MSNBC 1553 Alt Rock Classics 1575 Y2K 492 MTV Live HD 12/412 CBS 12 WPEC (HD) 86 MTV 1569 Bluegrass Subscribe to HD service and get: 478 Nat Geo Wild HD 93 CMT 19 My 15 WTCN-TV 1591 Broadway 488 A&E HD 490 National Geographic HD 48 CNBC 243 Nat Geo Wild 1573 Chamber Music 508 Alive TV HD 446 NBA TV HD 49 CNN 247 National Geographic 1598 Classic Masters 420 Animal Planet HD 456 NBC Sports Network -

Fios® TV California Business Channel Lineup and TV Guide

® FiOS TV Business Channel Lineup Effective February 2018 ©2018 Frontier Communications California Welcome to FiOS Got Questions? Get Answers. Whenever you have questions or need help with your FiOS TV service, we make it easy to get the answers you need. Here’s how: • On your TV, tune to channel 131 to find help videos for everything from filtering for your favorite channels to setting up a PIN for parental controls and purchases. • Online, go to Frontier.com/helpcenter to find the FiOS Triple Play User Guide to get help with your Internet and Voice services, as well as detailed instructions on how to make the most of your TV service. 3 Quick Reference Channels are grouped by programming categories in the following ranges: Local Channels 1–49 SD, 501–549 HD Local Public/Education/Government (varies by location) 15–47 SD Entertainment 50–69 SD, 550–569 HD Sports 70–99 & 300–319 SD, 570–599 HD News 100–119 SD, 600–619 HD Info & Education 120–139 SD, 620–639 HD Home & Leisure/Marketplace 140–179 SD, 640–679 HD Pop Culture 180–199 SD, 680–699 HD Music 210–229 SD, 710–729 HD Movies/Family 230–249 SD, 730–749 HD Kids 250–269 SD, 780–789 HD People & Culture 270–279 SD Religion 280–299 SD Premium Movies 340–449 SD, 840–949 HD* Subscription Sports 1000–1499* Spanish Language 1500–1760 * Available for Private Viewing only 4 Preferred HD ESPN2 74/574 HD FiOS TV Local Package included. EVINE Live 157/657 HD Additional subscriptions may be added. -

SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES Gender

Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. & Hum. 29 (1): 489 - 508 (2021) SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES Journal homepage: http://www.pertanika.upm.edu.my/ Gender Stereotyping in TV Drama in Pakistan: A Longitudinal Study Qurat-ul-Ain Malik1* and Bushra Hameed-ur-Rahman2 1Department of Media and Communication Studies, International Islamic University, 44000 Islamabad, Pakistan 2Institute of Communication Studies, University of the Punjab, 54000 Lahore, Pakistan ABSTRACT The research was aimed at analysing gender portrayal in TV drama in Pakistan over a period of five decades from its very inception in the late 1960’s till 2017. The research explored what types of gender stereotypes were being propagated in the prime time drama serials on the State owned TV channel, PTV which was the only platform available for most part of this duration. The methodology adopted for the research was quantitative in nature and involved a content analysis of the most popular Urdu serials aired between 1968 and 2017. The research focused on the three main characters in each drama and the total sample comprised 72 characters. These characters were analysed in a total of 4834 scenes to observe the display of gender stereotypes. The findings indicated that although overall both the genders were displaying their gender specific stereotypes yet some stereotypes such as bravery and aggressiveness were not being displayed by males and passivity, victimization and fearfulness were not being displayed by females. Later the 50 year time period was sub-divided into five decades to ARTICLE INFO observe whether there had been a change over the years keeping in view the massive Article history: Received: 5 September 2020 changes which had taken place in society.