Lost in the Borderlines Between User-Generated Content and the Cultural Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOST with a Good Book

The Lost Code: BYYJ C`1 P,YJ- LJ,1 Key Literary References and Influ- Books, Movies, and More on Your Favorite Subjects Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad CAS A CONR/ eAudiobook LOST on DVD A man journeys through the Congo and Lost Complete First Season contemplates the nature of good and evil. There are several references, especially in relation to Lost Season 2: Extended Experience Colonel’s Kurtz’s descent toward madness. Lost Season 3: The Unexplored Experience Lost. The Complete Fourth Season: The Expanded The Stand by Stephen King FIC KING Experience A battle between good and evil ensues after a deadly virus With a Good Book decimates the population. Producers cite this book as a Lost. The Complete Fifth Season: The Journey Back major influence, and other King allusions ( Carrie , On Writing , *Lost: Complete Sixth & Final Season is due for release 8/24/10. The Shining , Dark Tower series, etc.) pop up frequently. The Odyssey by Homer FIC HOME/883 HOME/ CD BOOK 883.1 HOME/CAS A HOME/ eAudiobook LOST Episode Guide Greek epic about Odysseus’s harrowing journey home to his In addition to the biblical episode titles, there are several other Lost wife Penelope after the Trojan War. Parallels abound, episode titles with literature/philosophy connections. These include “White especially in the characters of Desmond and Penny. Rabbit” and “Through the Looking Glass” from Carroll’s Alice books; “Catch-22”; “Tabula Rosa” (philosopher John Locke’s theory that the Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut FIC VON human mind is a blank slate at birth); and “The Man Behind the Curtain” A World War II soldier becomes “unstuck in time,” and is and “There’s No Place Like Home” ( The Wonderful Wizard of Oz ). -

Trauma, Fear, and Paranoia Lost and the Culture of 9/11

Trauma, fear, and Paranoia Lost and the Culture of 9/11 rachEl aldrich onE of thE Most popular tElEvision shoWs of thE last dEcadE, Lost (2004-2010) con- foundEd Many of its viewers With its tWisting, convolutEd plotlinEs. this articlE is an EXploration of thE Many ElEMEnts of thE shoW ovEr its first few, dynaMic yEars that ultiMatEly weavE togEthEr to forM a suBtlE, suBvErsivE iMagE of post-9/11 aMEri- can sociEty. through an EXaMination of spEcific charactErs, and thE cast as a WholE, as well as various distinctly tErroristic and apocalyptic coMponEnts of thE shoW’s plot, Lost is rEvEalEd as Both a rEproduction and a critical rE-iMagination of thE aMErican rEsponsE to thE EvEnts of sEptEMBEr 11th, 2001. Lost BEcoMEs not MErEly an artifact of post-9/11 aMErican sociEty But a MEans through Which viewers arE invitEd to sEE Ways in Which our World can groW and changE. The events of September 11, 2001, not only permanently subtle. The first scene of the pilot episode depicts Jack disfigured the face of New York City and greatly changed Shephard (Matthew Fox), a surgeon and the main charac- the lives of thousands of Americans, but also created a cul- ter of the series, sprawled on the ground in the middle of tural shockwave in America that is still felt today. Ameri- the jungle. He is wearing a tattered business suit and looks can society was transformed almost immediately after the remarkably like a corpse. The positioning of his body and attacks; this response to terror can be seen in much of the his costuming is meant to align him with those many vic- visual culture that followed. -

Learning from Ambiguously Labeled Images

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Technical Reports (CIS) Department of Computer & Information Science January 2009 Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images Timothee Cour University of Pennsylvania Benjamin Sapp University of Pennsylvania Chris Jordan University of Pennsylvania Ben Taskar University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports Recommended Citation Timothee Cour, Benjamin Sapp, Chris Jordan, and Ben Taskar, "Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images", . January 2009. University of Pennsylvania Department of Computer and Information Science Technical Report No. MS-CIS-09-07 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports/902 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images Abstract In many image and video collections, we have access only to partially labeled data. For example, personal photo collections often contain several faces per image and a caption that only specifies who is in the picture, but not which name matches which face. Similarly, movie screenplays can tell us who is in the scene, but not when and where they are on the screen. We formulate the learning problem in this setting as partially-supervised multiclass classification where each instance is labeled ambiguously with more than one label. We show theoretically that effective learning is possible under reasonable assumptions even when all the data is weakly labeled. Motivated by the analysis, we propose a general convex learning formulation based on minimization of a surrogate loss appropriate for the ambiguous label setting. We apply our framework to identifying faces culled from web news sources and to naming characters in TV series and movies. -

LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy

"Accidental Intellectuals": LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy Author: Abigail Letak Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2615 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This thesis is dedicated to everyone who has ever been obsessed with a television show. Everyone who knows that adrenaline rush you get when you just can’t stop watching. Here’s to finding yourself laughing and crying along with the characters. But most importantly, here’s to shows that give us a break from the day-to-day milieu and allow us to think about the profound, important questions of life. May many shows give us this opportunity as Lost has. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my parents, Steve and Jody, for their love and support as I pursued my area of interest. Without them, I would not find myself where I am now. I would like to thank my advisor, Juliet Schor, for her immense help and patience as I embarked on combining my personal interests with my academic pursuits. Her guidance in methodology, searching the literature, and general theory proved invaluable to the completion of my project. I would like to thank everyone else who has provided support for me throughout the process of this project—my friends, my professors, and the Presidential Scholars Program. I’d like to thank Professor Susan Michalczyk for her unending support and for believing in me even before I embarked on my four years at Boston College, and for being the one to initially point me in the direction of sociology. -

LOST the Official Show Auction Catalog

LOST | The Auction 70 1-310-859-7701 Profiles in History | August 21 & 22, 2010 221. JACK’S SEASON TWO COSTUME. Jack’s blue jeans, blue t-shirt and shoes worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 219. JACK’S SEASON TWO COSTUME. Jack’s blue jeans and green t-shirt worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 220. JACK’S SEASON TWO COS- TUME. Jack’s blue jeans and gray t-shirt worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 222. JACK’S MEDICAL BAG. Dark brown leather shoulder bag used by Jack in Season Two to carry medical supplies. $200 – $300 71 www.liveauctioneers.com LOST | The Auction 225. KATE’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “WHAT KATE DID.” Kate’s brown corduroy pants, brown print t-shirt, and jean jacket worn in the episode, “What Kate Did.” $200 – $300 223. KATE’S SEASON TWO ISLAND COS- TUME. Kate’s white tank top, beige long- sleeve shirt and brown corduroy cargo pants worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 224. KATE’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “WHAT KATE DID.” Kate’s jeans, jean jacket and Janis Joplin print shirt worn in the episode, “What Kate Did.” $200 – $300 226. HURLEY’S SEASON TWO COSTUMES. Hurley’s olive green shorts and red t- shirt worn on the Island in the episode, “S.O.S..” Includes Hurley’s black jeans, gray t-shirt and black hoodie worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 72 1-310-859-7701 Profiles in History | August 21 & 22, 2010 227. HURLEY’S MR. CLUCK’S CHICKEN SHACK COSTUME. Hurley’s black pants, green Mr. -

10 Lost Wanted

Wanted updated 03-12-13 LOST Season 1 Missing: Oceanic 815 Puzzle Cards (1:11 packs) M1 Charlie: Get it? Hurley: Dude, quit asking me Walkabout M3 Claire: I'm having contractions. Jack: How man Pilot Pt. 1 M4 Jack: Come on. Come on! Come on! Come on! Big Pilot Pt. 1 M5 Jack: We must have been at about forth thousan Pilot Pt. 1 M6 Michael: Hey, hey, where you going, man? Walt: Walkabout M7 Charlie: How does something like that happen? Pilot Pt. 1 M8 Pilot: Six hours in, our radio went out. No on Pilot Pt. 1 M9 Kate: Jack! Jack: There's someone else still o White Rabbit Numbers Die-Cut Cards (1:17 packs) 15 Sawyer: That what I think it is? Michael: Some Exodus, Pt. 2 23 Kate: I wanted you to make sure that Ray Mulle Tabula Rasa 42 Hurley: ...Stop! What are you doing?! Why'd yo Exodus, Pt. 2 Autograph Cards (1:36 packs) A-1 Evangeline Lilly as Kate Austen A-2 Josh Holloway as James "Sawyer" Ford A-3 Maggie Grace as Shannon Rutherford A-5 Mira Furlan as Danielle Rousseau A-6 William Mapother as Ethan Rom A-7 John Terry as Dr. Christian Shephard A-9 Daniel Roebuck as Dr. Leslie Arzt A-11 Kevin Tighe as Anthony Cooper A-12 Swoosie Kurtz as Emily Annabeth Locke AR1 (Redemption Card) Pieceworks Cards (1:36 packs) PW-1 Shirt worn by Evangeline Lilly as Kate Austen The Greater Good PW-2 T-shirt worn by Josh Holloway as Sawyer Ford Pilot PW-3 Top worn by Maggie Grace as Shannon Rutherford Hearts and Minds PW-4 T-shirt worn by Matthew Fox as Jack Shepherd All the Best Cowboys Have Daddy Issues PW-5 T-shirt worn by Dominic Monaghan as Charlie Pace Pilot PW-6 T-shirt worn by Terry O'Quinn as John Locke Numbers PW-8 T-shirt worn by Jorge Garcia as Hugo "Hurley" Reyes Hearts and Mind PW-10 Top worn by Yunjin Kim as Sun Kwon Exodus Pt. -

The Etiology of Character Realization, Within Rhetorical Analysis of the Series

i Found: The Etiology of Character Realization, within Rhetorical Analysis of the Series LOST, through the Application of Underhill’s and Turner’s Classic Concepts of the Mystic Journey ____________________________________________ Presented to the Faculty Liberty University School of Communication Studies ______________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication By Lacey L. Mitchell 2 December 2010 ii Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in Communication Studies Michael P. Graves Ph.D., Chair Carey Martin Ph.D., Reader Todd Smith M.F.A, Reader iii Dedication For James and Mildred Renfroe, and Donald, Kim and Chase Mitchell, without whom this work would have been remiss. I am forever grateful for your constant, unwavering support, exemplary resolve, and undiscouraged love. iv Acknowledgements This work represents the culmination of a remarkable journey in my life. Therefore, it is paramount that I recognize several individuals I found to be indispensible. First, I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Michael Graves, for taking this process and allowing it to be a learning and growing experience in my own journey, providing me with unconventional insight, and patiently answering my never ending list of inquiries. His support through this process pushed me towards a completed work – Thank you. I also owe a great debt to the readers on my committee, Dr. Cary Martin and Todd Smith, who took time to ensure the completion of the final product. I will always have immense gratitude for my family. Each of them has an incredible work ethic and drive for life that constantly pushes me one step further. -

The Vilcek Foundation Celebrates a Showcase Of

THE VILCEK FOUNDATION CELEBRATES A SHOWCASE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS AND FILMMAKERS OF ABC’S HIT SHOW EXHIBITION CATALOGUE BY EDITH JOHNSON Exhibition Catalogue is available for reference inside the gallery only. A PDF version is available by email upon request. Props are listed in the Exhibition Catalogue in the order of their appearance on the television series. CONTENTS 1 Sun’s Twinset 2 34 Two of Sun’s “Paik Industries” Business Cards 22 2 Charlie’s “DS” Drive Shaft Ring 2 35 Juliet’s DHARMA Rum Bottle 23 3 Walt’s Spanish-Version Flash Comic Book 3 36 Frozen Half Wheel 23 4 Sawyer’s Letter 4 37 Dr. Marvin Candle’s Hard Hat 24 5 Hurley’s Portable CD/MP3 Player 4 38 “Jughead” Bomb (Dismantled) 24 6 Boarding Passes for Oceanic Airlines Flight 815 5 39 Two Hieroglyphic Wall Panels from the Temple 25 7 Sayid’s Photo of Nadia 5 40 Locke’s Suicide Note 25 8 Sawyer’s Copy of Watership Down 6 41 Boarding Passes for Ajira Airways Flight 316 26 9 Rousseau’s Music Box 6 42 DHARMA Security Shirt 26 10 Hatch Door 7 43 DHARMA Initiative 1977 New Recruits Photograph 27 11 Kate’s Prized Toy Airplane 7 44 DHARMA Sub Ops Jumpsuit 28 12 Hurley’s Winning Lottery Ticket 8 45 Plutonium Core of “Jughead” (and sling) 28 13 Hurley’s Game of “Connect Four” 9 46 Dogen’s Costume 29 14 Sawyer’s Reading Glasses 10 47 John Bartley, Cinematographer 30 15 Four Virgin Mary Statuettes Containing Heroin 48 Roland Sanchez, Costume Designer 30 (Three intact, one broken) 10 49 Ken Leung, “Miles Straume” 30 16 Ship Mast of the Black Rock 11 50 Torry Tukuafu, Steady Cam Operator 30 17 Wine Bottle with Messages from the Survivor 12 51 Jack Bender, Director 31 18 Locke’s Hunting Knife and Sheath 12 52 Claudia Cox, Stand-In, “Kate 31 19 Hatch Painting 13 53 Jorge Garcia, “Hugo ‘Hurley’ Reyes” 31 20 DHARMA Initiative Food & Beverages 13 54 Nestor Carbonell, “Richard Alpert” 31 21 Apollo Candy Bars 14 55 Miki Yasufuku, Key Assistant Locations Manager 32 22 Dr. -

Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janeiro Centro De

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO PATRÍCIA SILVA DE AZEREDO QUE MULHER VOCÊ SERIA EM UMA ILHA DESERTA? Aspectos da representação do feminino no seriado de TV Lost RIO DE JANEIRO 2007 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO Patrícia Silva de Azeredo QUE MULHER VOCÊ SERIA EM UMA ILHA DESERTA? Aspectos da representação do feminino no seriado de TV Lost Trabalho de conclusão de curso de graduação apresentado à Escola de Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Bacharel em Comunicação Social com habilitação em Jornalismo. Orientador: João Freire Filho Rio de Janeiro 2007 Patrícia Silva de Azeredo QUE MULHER VOCÊ SERIA EM UMA ILHA DESERTA? Aspectos da representação do feminino no seriado de TV Lost Trabalho de conclusão de curso de graduação apresentado à Escola de Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Bacharel em Comunicação Social com habilitação em Jornalismo . Aprovada em: ________________________ Prof. Dr. João Batista de Macedo Freire Filho, professor-adjunto, ECO/UFRJ ________________________ Profa. Doutoranda Mônica Machado Cardoso Rebello, professora-assistente, ECO/UFRJ ________________________ Prof. Dr. Paulo Roberto Gibaldi Vaz, professor-adjunto, ECO/UFRJ RESUMO AZEREDO, Patrícia. Que mulher você seria em uma ilha deserta? Aspectos da representação do feminino no seriado de TV Lost. Rio de Janeiro, 1996. Monografia (Graduação em Comunicação Social – Habilitação Jornalismo) – Escola de Comunicação, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2007; O trabalho busca analisar aspectos da representação do feminino nas três temporadas do seriado de TV norte-americano Lost, exibido no Brasil pelo canal AXN e pela Rede Globo. -

From William Golding's Lord of the Flies to ABC's LOST. By

Humanity Square One: From William Golding’s Lord of the Flies to ABC’s LOST. by Antonia Iliadou A dissertation to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki September 2013 Humanity Square One: From William Golding’s Lord of the Flies to ABC’s LOST. by Antonia Iliadou Has been approved September 2013 APPROVED: _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ Supervisory Committee ACCEPTED: _______________ Department Chairperson Iliadou 1 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................1 ABSTRACT...............................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1: William Golding’s Lord of the Flies: Analysis and Contextualization ..............1 1.1. a. Lord of the Flies in an age of ambiguity: The position of Golding’s novel in the Post War United States...........................................................................................................2 1.1. b. The Impact of Golding’s Lord of the Flies on its Readers........................................14 1.2. “… The picture of man, at once heroic and sick”: The Depiction -

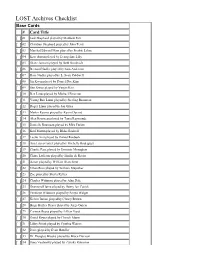

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika -

Table of Contents GETTING STARTED

Table of ConTenTs GETTING STARTED....................................... 2 System Requirements .................................. 2 Installation .......................................... 3 CONTROLS ............................................ 4 INTRODUCTION ......................................... 4 CHARACTERS .......................................... 5 THE GAME ............................................ 8 WARRANTY................................ inside front cover TECHNICAL SUPPORT ........................inside back cover LOS70147_PCS_MNL_guts 1 2/1/08 2:40:51 PM GeTTInG sTaRTeD Installation System Requirements Installing LOST™: Via Domus Insert the LOST: Via Domus DVD into your DVD-ROM drive and follow the Supported OS: Windows Vista®/Windows® XP (only) instructions that appear on-screen. Processor: 2.4 GHz Intel Pentium® 4C or AMD Athlon™ MP 2400+ If installation does not start automatically: (3.5 GHz Pentium 4/AMD Athlon or 2.5 GHz Core 2 Duo/Athlon 64 X2 recommended) 1. Insert the LOST: Via Domus DVD into your DVD-ROM drive. RAM: 1 GB (2 GB recommended) 2. Open the My Computer icon on your Desktop and then double-click the icon for your DVD-ROM drive. Video Card: 128 MB DirectX® 9.0c–compliant, Shader 3.0–enabled video card (256 MB recommended) (see supported list)* 3. Click on autorun.exe. Sound Card: DirectX 9.0c–compliant sound card Follow the on-screen instructions to complete the installation. DirectX Version: 9.0c (included on disc) Uninstalling LOST: Via Domus DVD-ROM: 4x DVD-ROM drive To uninstall the game, click on the Game Uninstall icon in the Start Hard Drive Space: 5 GB menu. Follow the uninstallation wizard guide to successfully uninstall the Peripherals Supported: Mouse, keyboard, Windows-compliant gamepad or game from your computer. joystick *Supported Video Cards at Time of Release: ATI® RADEON® X1300-1950/HD 2000 series NVIDIA GeForce® 6600-6800/7/8 series Laptop versions of these cards may work but are NOT supported.