Print-At-Home Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] YUJA WANG to Repla

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ARTIST CHANGE March 21, 2019 Contact: Deirdre Roddin (212) 875-5700; [email protected] YUJA WANG To Replace Maurizio Pollini In One-Night-Only Performance of SCHUMANN’s Piano Concerto Conducted by MUSIC DIRECTOR JAAP VAN ZWEDEN Program Also To Include J. WAGENAAR’s Cyrano de Bergerac Overture BEETHOVEN’s Symphony No. 7 March 27, 2019 Yuja Wang will replace Maurizio Pollini, who has cancelled in order to fully recover from a brief illness, in the one-night-only performance of Schumann’s Piano Concerto with the New York Philharmonic led by Music Director Jaap van Zweden, Wednesday, March 27, 2019, at 7:30 p.m. The program will also include Johan Wagenaar’s Cyrano de Bergerac Overture and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7. The performance will mark Yuja Wang’s 24th with the New York Philharmonic; she most recently appeared with the Orchestra and Jaap van Zweden in February–March 2018, both in New York and on tour to Asia. She will return next season for performances of Shostakovich’s Concerto No. 1 for Piano, Trumpet, and Strings, June 11–13, 2020, also conducted by Jaap van Zweden and featuring Principal Trumpet Christopher Martin. The Boston Globe wrote of her performance of Schumann’s Piano Concerto last month with the Boston Symphony Orchestra: “Not just a vehicle for virtuosic fireworks, the concerto calls for a keen listening ear and attunement to the larger ensemble… Wang demonstrated all that in spades. Like an elite figure skater or gymnast, the athletic effort she expended was palpable, but if the physical feats took any toll, the audience never saw it.” Biographies Beijing-born pianist Yuja Wang is set to achieve new heights in critical superlatives and audience ovations during the 2018–19 season, through recitals, concert series, season residencies, and extensive tours with some of the world’s most venerated ensembles and conductors. -

Grieg & Musical Life in England

Grieg & Musical Life in England LIONEL CARLEY There were, I would prop ose, four cornerstones in Grieg's relationship with English musicallife. The first had been laid long before his work had become familiar to English audiences, and the last was only set in place shortly before his death. My cornerstones are a metaphor for four very diverse and, you might well say, ve ry un-English people: a Bohemian viol inist, a Russian violinist, a composer of German parentage, and an Australian pianist. Were we to take a snapshot of May 1906, when Grieg was last in England, we would find Wilma Neruda, Adolf Brodsky and Percy Grainger all established as significant figures in English musicallife. Frederick Delius, on the other hand, the only one of thi s foursome who had actually been born in England, had long since left the country. These, then, were the four major musical personalities, each having his or her individual and intimate connexion with England, with whom Grieg established lasting friendships. There were, of course, others who com prised - if I may continue and then finally lay to rest my architectural metaphor - major building blocks in the Grieg/England edifice. But this secondary group, people like Francesco Berger, George Augener, Stop ford Augustus Brooke, for all their undoubted human charms, were firs t and foremost representatives of British institutions which in their own turn played an important role in Grieg's life: the musical establishment, publishing, and, perhaps unexpectedly religion. Francesco Berger (1834-1933) was Secretary of the Philharmonic Soci ety between 1884 and 1911, and it was the Philharmonic that had first prevailed upon the mature Grieg to come to London - in May 1888 - and to perform some of his own works in the capital. -

Frederica Von Stade

FREDERICA VON STADE Mezzo-soprano Described by the New York Times as "one of America's finest artists and singers," Frederica von Stade continues to be extolled as one of the music world's most beloved figures. Known to family, friends, and fans by her nickname "Flicka," the mezzo-soprano has enriched the world of classical music for three decades. Miss von Stade's career has taken her to the stages of the world's great opera houses and concert halls. She began at the top, when she received a contract from Sir Rudolf Bing during the Metropolitan Opera auditions, and since her debut in 1970 she has sung nearly all of her great roles with that company. In January 2000, the company celebrated the 30th anniversary of her debut with a new production of The Merry Widow specifically for her, and in 1995, as a celebration of her 25th anniversary, the Metropolitan Opera created for her a new production of Pelléas et Mélisande. In addition, Miss von Stade has appeared with every leading American opera company, including San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Los Angeles Opera. Her career in Europe has been no less spectacular, with new productions mounted for her at Teatro alla Scala, Royal Opera Covent Garden, the Vienna State Opera, and the Paris Opera. She is invited regularly by the finest conductors, among them Claudio Abbado, Charles Dutoit, James Levine, Kurt Masur, Riccardo Muti, Seiji Ozawa, André Previn, Leonard Slatkin, and Michael Tilson Thomas, to appear in concert with the world's leading orchestras, including the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, London Symphony Orchestra, Washington's National Symphony, and the Orchestra of La Scala. -

ANNOUNCING the 2013-2014 SEASON of the OSM the Orchestre Symphonique De Montréal Celebrates Its 80Th Season

ANNOUNCING THE 2013-2014 SEASON OF THE OSM The Orchestre symphonique de Montréal celebrates its 80th season Great works conducted by Kent Nagano: Opening the season: Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust and Symphony fantastique Mahler’s Symphony No. 7, Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3, Beethoven’s Symphonies Nos. 2 and 4, Bach’s Mass in B Minor, Brahms’s Symphony No. 3 Concluding the season: three concerts, including Saint-Saëns’s Symphony No. 3, and an open-door day to inaugurate the Grand Orgue Pierre Béique Premiere of eight new works: Arcuri, Bertrand, Gilbert, Good, Hatzis, Hefti, Ryan, Saariaho Groundbreaking programs: OSM artist in residence: James Ehnes Introduction of the series OSM Express OSM Éclaté: focusing on Beethoven and Frank Zappa Second edition of Fréquence OSM Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition in collaboration with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts Two programs with the OSM Chamber Choir conducted by Andrew Megill Prestigious guest conductors and soloists, including conductors Jean-Claude Casadesus, James Conlon, Sir Andrew Davis and Michel Plasson, pianists Yuja Wang, Radu Lupu, Stephen Hough, Marc-André Hamelin and Jan Lisiecki cellists Truls Mørk, Gautier Capuçon and Jian Wang violinists Gidon Kremer and Midori, violist Pinchas Zukerman soprano Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo-soprano Ann Hallenberg, tenor Michael Schade and bass-baritone Philippe Sly A new Christmas story recounted by Fred Pellerin Music & Imagery: Beethoven’s Fifth OSM Pops: Hats off to Les Belles-sœurs and La Symphonie rapaillée Symphonic Duo: Adam Cohen -

Beyond the Storm

Pamela J. Marshall Beyond the Storm oboe collection of Poetry-Inspired Solos PREVIEWSpindrift Music Company www.spindrift.com Publishing contemporary classical music and promoting its performance and appreciation collection of Poetry-Inspired Solos Beyond the Storm by Pamela J. Marshall for oboe La Mer by Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) From Poems, 1881 A white mist drifts across the shrouds, A wild moon in this wintry sky Gleams like an angry lion's eye Out of a mane of tawny clouds. The muffled steersman at the wheel Is but a shadow in the gloom;-- And in the throbbing engine-room Leap the long rods of polished steel. The shattered storm has left its trace Upon this huge and heaving dome, For the thin threads of yellow foam Float on the waves like ravelled lace. PREVIEWSpindrift Music Company www.spindrift.com aer "La Mer" by Oscar Wilde Beyond the Storm Pamela J. Marshall Andante misterioso, con licenza q = 86 Oboe p p mp pp mp pp 2 p pp mp 4 (like a throbbing engine) 5 (as if two voices, staccato notes extremely clipped) 11 mp pp 15 18 mp pp pp 21 pp mp 26 mp 27 PREVIEW Copyright © 2007 Pamela J. Marshall 28 mf 29 f 33 mf 38 p mp 43 mf 48 mp 51 pp 54 mp p 57 p mf 61 PREVIEWmp 64 p ppp 2 Spindrift Music Company Publishing contemporary classical music and promoting its performance and appreciation 38 Dexter Road Lexington MA 02420-3304 USA 781-862-0884 [email protected] www.spindrift.com Selected Music by Pamela J. -

Christianialiv

Christianialiv Works from Norway’s Golden Age of wind music Christianialiv The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces The second half of the 19th century is often called the “Golden Age” of Norwegian music. The reason lies partly in the international reputations established by Johan Svendsen and Edvard Grieg, but it also lies in the fact that musical life in Norway, at a time of population growth and economic expansion, enjoyed a period of huge vitality and creativity, responding to a growing demand for music in every genre. The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces (to use its modern name) played a key role in this burgeoning musical life not just by performing music for all sections of society, but also by discovering and fostering musical talent in performers and composers. Johan Svendsen, Adolf Hansen, Ole Olsen and Alfred Evensen, whose music we hear on this album, can therefore be called part of the band’s history. Siste del av 1800-tallet er ofte blitt kalt «gullalderen» i norsk musikk. Det skyldes ikke bare Svendsens og Griegs internasjonale posisjon, men også det faktum at musikklivet i takt med befolkningsøkning og økonomiske oppgangstider gikk inn i en glansperiode med et sterkt behov for musikk i alle sjangre. I denne utviklingen spilte Forsvarets stabsmusikkorps en sentral rolle, ikke bare som formidler av musikkopplevelser til alle lag av befolkningen, men også som talentskole for utøvere og komponister. Johan Svendsen, Adolf Hansen, Ole Olsen og Alfred Evensen er derfor en del av korpsets egen musikkhistorie. The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces / Ole Kristian Ruud Recorded in DXD 24bit/352.8kHz 5.1 DTS HD MA 24/192kHz 2.0 LPCM 24/192kHz + MP3 and FLAC EAN13: 7041888519027 q e 101 2L-101-SABD made in Norway 20©14 Lindberg Lyd AS 7 041888 519027 Johan Svendsen (1840-1911) Symfoni nr. -

TEM Issue 16 Cover and Front Matter

TEMPSUMMER O1950 CONTENTS • NOTES AND NEWS SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY * MUSIC FESTIVALS BRITISH FESTIVALS : SOME COMMENTS ON THEIR CUSTOMS Donald Mitchell THE NORDIC MUSIC FESTIVALS : 1888-1938 Jiirgen Balzer ITALIAN MUSIC FESTIVALS Guido M. Gatti MUSICAL LIFE IN GERMANY SINCE THE WAR Walther Harth TANGLEWOOD AFTER TEN YEARS Ralph Hawkes * PRODUCING ELEKTRA Stephen Beinl BOOK GUIDE NUMBER QUARTERLY 16TWO SHILLINGS Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.40, on 24 Sep 2021 at 10:17:38, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298200043369 His Masters Voice" Special lAst €€€€- The contents of the " Special List" are of great interest to the serious record buyer, for they represent the best of international recorded art that is not included in the General Record Catalogue. In many cases " Special List" recordings are the only versions available. They explore the high- ways and byways of music with fascinating results. Available from " His Master's Voice" Dealers to Special Order. Here are the latest additions:— RAVEL SCHONBERG Quartet in F Major Verklarte Nacht, Op. 4 Paganini Quartet - DB 9452-5 St. Louis Symphony Orchestra cond. by Vladimir Golschmann JANACEK DB 9280-3 Sinfonietta Czech Philharmonic Orchestra SCHUBERT conducted by Rafael Kubelik Quartet in G Major — Op. 161 C 7671-3 Hungarian String Quartet BRAHMS DB 9331-5 Concerto No. 1 in D Minor STRAVINSKY Claudia Arrau and The Rite of Spring The Philharmonia Orchestra San Francisco Symphony Orch. HIS MASTERS VOICE conducted by Basil Cameron conducted by Pierre Monteux DB 9250-55 DB 9409-12 All records in Automatic Couplings only THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY LIMITED. -

Fall/Winter 2002/2003

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Fall/ Winter 2002 Bernstein's Mahler: A Personal View @ by Sedgwick Clark n idway through the Adagio £male of Mahler's Ninth M Symphony, the music sub sides from an almost desperate turbulence. Questioning wisps of melody wander throughout the woodwinds, accompanied by mut tering lower strings and a halting harp ostinato. Then, suddenly, the orchestra "vehemently burst[s] out" fortissimo in a final attempt at salvation. Most conductors impart a noble arch and beauty of tone to the music as it rises to its climax, which Leonard Bernstein did in his Vienna Philharmonic video recording in March 1971. But only seven months before, with the New York Philharmonic, His vision of the music is neither Nearly all of the Columbia cycle he had lunged toward the cellos comfortable nor predictable. (now on Sony Classical), taped with a growl and a violent stomp Throughout that live performance I between 1960 and 1974, and all of on the podium, and the orchestra had been struck by how much the 1980s cycle for Deutsche had responded with a ferocity I more searching and spontaneous it Grammophon, are handily gath had never heard before, or since, in was than his 1965 recording with ered in space-saving, budget-priced this work. I remember thinking, as the orchestra. Bernstein's Mahler sets. Some, but not all, of the indi Bernstein tightened the tempo was to take me by surprise in con vidual releases have survived the unmercifully, "Take it easy. Not so cert many times - though not deletion hammerschlag. -

Norsk Tidend 2-18

Vil auke medvitet Ny bokklubb Mannen bak guten RETURADRESSE: – Kommunane må bli Forlaget Skald satsar hardt Olav Olavsson Edland, eller medvitne om ansvaret dei på omsett verdslitteratur. Storegut som han vart Noregs Mållag har, seier Synnøve Midtbø – Dette er ein måte kalla, var ein myteom- Lilletorget 1 Myking, som har under- å utvikle språket på, spunnen kar lenge 0184 OSLO søkt digitale læremiddel på seier forlagssjef Simone før A. O. Vinje skreiv nynorsk. Stibbe. om han. SIDE 6–7 SIDE 14–15 SIDE 18–19 nr. 2 Norsk Tidend mars 2018 medlemsblad for Noregs Mållag Vil ha meir nynorsk i Oslo- skulen Halvparten av lærebøkene på nynorsk • Tidleg start • Bruke språket i andre fag enn norsk • Mindre fritak. Khamshajiny «Kamzy» Gunaratnam, varaordførar i Oslo, tek til orde for å satse på nynorsk i skulen. – Så lenge vi har to offisielle språk, så må samfunnet leggje til rette for at vi lærer oss båe. SIDE 8–9 FOTO: OSLO KOMMUNE / STURLASON 2 • 2018 Norsk Tidend Framhald av Fedraheimen og Den 17de Mai Tunnelsyn i skulen ҡ Ei veninne av meg var ute og svinga seg på ein utestad i Oslo. Då det var nok dansing, tok ho jakka si og gjekk ut. Ein kar kom springande etter og lurte på om ho ikkje hadde lyst til å vera med ein annan stad. Men då veninna mi svara, sa han berre: «Hva!? Vestlandet?!», snudde og gjekk inn att. Nynorsk ҡ Men før Oslo-hatet får fotfeste, så skal eg skunde meg å fortelje ei anna soge. Ein slektning er læ- rar på ein vidaregåande skule på Voss. -

2017–2018 Season Artist Index

2017–2018 Season Artist Index Following is an alphabetical list of artists and ensembles performing in Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage (SA/PS), Zankel Hall (ZH), and Weill Recital Hall (WRH) during Carnegie Hall’s 2017–2018 season. Corresponding concert date(s) and concert titles are also included. For full program information, please refer to the 2017–2018 chronological listing of events. Adès, Thomas 10/15/2017 Thomas Adès and Friends (ZH) Aimard, Pierre-Laurent 3/8/2018 Pierre-Laurent Aimard (SA/PS) Alarm Will Sound 3/16/2018 Alarm Will Sound (ZH) Altstaedt, Nicolas 2/28/2018 Nicolas Altstaedt / Fazil Say (WRH) American Composers Orchestra 12/8/2017 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) 4/6/2018 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) Anderson, Laurie 2/8/2018 Nico Muhly and Friends Investigate the Glass Archive (ZH) Angeli, Paolo 1/26/2018 Paolo Angeli (ZH) Ansell, Steven 4/13/2018 Boston Symphony Orchestra (SA/PS) Apollon Musagète Quartet 2/16/2018 Apollon Musagète Quartet (WRH) Apollo’s Fire 3/22/2018 Apollo’s Fire (ZH) Arcángel 3/17/2018 Andalusian Voices: Carmen Linares, Marina Heredia, and Arcángel (SA/PS) Archibald, Jane 3/25/2018 The English Concert (SA/PS) Argerich, Martha 10/20/2017 Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (SA/PS) 3/22/2018 Itzhak Perlman / Martha Argerich (SA/PS) Artemis Quartet 4/10/2018 Artemis Quartet (ZH) Atwood, Jim 2/27/2018 Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra (SA/PS) Ax, Emanuel 2/22/2018 Emanuel Ax / Leonidas Kavakos / Yo-Yo Ma (SA/PS) 5/10/2018 Emanuel Ax (SA/PS) Babayan, Sergei 3/1/2018 Daniil -

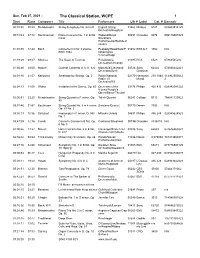

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Feb 07, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 09:23 Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 02 in D English String 01460 Nimbus 5141 083603514129 Orchestra/Boughton 00:12:2347:12 Stenhammar Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat Widlund/Royal 00391 Chandos 9074 095115907429 minor Stockholm Philharmonic/Rozhdest vensky 01:01:0517:24 Bach Concerto in D for 3 Violins, Peabody/Rood/Sato/P 01652 ESS.A.Y 1002 N/A BWV 1064 hilharmonia Virtuosi/Kapp 01:19:2909:47 Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Philadelphia 01095 RCA 6528 07863565282 Orchestra/Ormandy 01:30:4629:00 Mozart Clarinet Concerto in A, K. 622 Marcellus/Cleveland 03728 Sony 62424 074646242421 Orchestra/Szell Classical 02:01:1621:57 Karlowicz Serenade for Strings, Op. 2 Polish National 02170 Harmonia 278 1088 314902505612 Radio-TV Mundi 2 Orchestra/Wit 02:24:13 11:08 Weber Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65 Orchestra of the 03176 Philips 420 812 028942081222 Vienna People's Opera/Bauer-Theussl 02:36:5123:25 Mendelssohn String Quartet in F minor, Op. Talich Quartet 06241 Calliope 9313 794881725922 80 03:01:4631:57 Beethoven String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Smetana Quartet 00270 Denon 7033 N/A Op. 59 No. 2 03:35:1310:56 Schubert Impromptu in F minor, D. 935 Mitsuko Uchida 04691 Philips 456 245 028945624525 No. 1 03:47:0912:16 Corelli Concerto Grosso in B flat, Op. Cantilena/Shepherd 00794B Chandos 8336/7/8 N/A 6 No. 5 04:00:5514:27 Mozart Horn Concerto No. -

A List of Recommended Recordings (Weeks 1 Through 4)

A List of Recommended Recordings (Weeks 1 Through 4) Week One: France François-Joseph Gossec Selected Symphonies Matthias Bamert conducts the London Mozart Players, on Chandos Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique Michael Tilson Thomas conducts the San Francisco Symphony, on RCA Victor Charles Munch conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, on RCA Victor Harold in Italy Charles Munch conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, on RCA Victor Symphonie Funèbre et Triomphale Colin Davis conducts the London Symphony, on Philips Romeo et Juliette Carlo Maria Giulini conducts the Chicago Symphony, on DGG Camille Saint-Saëns Symphony No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 78 (Organ) Christoph Eschenbach conducts the Philadelphia Orchestra, on Ondine Edo De Waart conducts the San Francisco Symphony, on Philips César Franck Symphony in D Minor Pierre Monteux conducts the Chicago Symphony, on RCA Victor Vincent d’Indy Symphony on a French Mountain Air Charles Munch conducts the Boston Symphony, on RCA Victor Symphony No. 2, Op. 57 Pierre Monteux conducts the San Francisco Symphony, on Sony Classical (Pierre Monteux Edition, available from ArkivMusic.com as a low-cost reprint CD.) Ernest Chausson Symphony in B-flat Major, Op. 20 Pierre Monteux conducts the San Francisco Symphony, on Sony Classical (Pierre Monteux Edition, available from ArkivMusic.com as a low-cost reprint CD.) Olivier Messiaen Turangalîla Symphony Riccardo Chailly conducts the Concertgebouw Orchestra, on Decca Week Two: Bohemia The Symphonies of Antonin Dvořák Istvan Kertesz conducts the London Symphony Orchestra, on Decca Witold Rowicki conducts the London Symphony Orchestra, on Decca Individual Symphonies: Symphony No. 7 in D Minor Iván Fischer conducts the Budapest Festival Orchestra, on Channel Classics Symphony No.