And Others TITLE Teacher's Guide for Mapping. Elementary Science Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List 2019-2020

Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List 2019-2020 Compiled by Stacey Szklut MS, OTR/L & South Shore Therapies Staff Children learn through play and active exploration. The suggestions below may be helpful in choosing appropriate toys for holidays and other special times. They include sensory based activities to provide organizing sensation and encourage the development of body awareness, as well as games to promote eye- hand coordination, visual perception and planning. Approximate ages or skill levels have been given to help guide your choices. Many items can be purchased at toy stores or through the catalogues listed. Ask your occupational therapist for help in deciding which games or toys are the best choices for your child. Games to Develop Coordination, Problem Solving and Visual Perception: Younger Ages (3-6 years) Older Kids (7 and up) Acorn Soup Acuity Ants in the Pants Amazing Labyrinth Game Avalanche Fruit Stand Backseat Drawing Barbecue Party Batik Busytown (by Richard Scarry) Battleship Cat in the Hat I Can Do That! Blink Charades for Kids Blokus Cootie Bounce Off Crazy Cereal Brain vs Brain Puzzle Game (Young Explorers) Crocodile Hop Burger Mania Disney Jr Super Stretchy Game Cheese Louise Don’t Break the Ice Connect Four/ Conniption Don’t Spill the Beans Cover Your Tracks (Thinkfun) Dream Cakes Crab Stack Elefun Cranium Cadoo Elephant Balancing Game Crowded Waters Feed the Woozle Cubeez Frankie’s Food Truck Fiasco Doodle Dice Gobblet Gobblers Doodle Quest Gumball Grab (Lakeshore) Get the Picture Dot-to-Dot Race Hit the Hat Go Go Gelato Honey Bee Tree Guess Who Hungry Hungry Hippos Hang On Harvey I Spy Bingo and Memory Games IQ Fit Journey Through Time Eye Found it! Game Jenga Loopin’ Chewie/Loopin’ Louie Kerplunk/ Tumble Monkeying Around Laser Chess (Thinkfun) Mr. -

Wayne Hobby Center 34816 Michigan Ave., Wayne Plymouth Connect Four, Merlin, Mickey Mouse, P(Tch and Pop, Baby Be Good, Baby This and One Block East of Wayne Rd

m rm $7 C om m u n ity December 12,1979 The Newspaper with Its Heart in the Plymouth-Canton Community Voi. 6, No. 45 ‘I <’ •$ Rocks lose in oyertime pg. 62 400 enter C hristm as C olor C ontest lW g ra d -p r iK w iM trrfT W C <aiM»afcy C iiw ’i d a k a a O lw iin Coetert wee Ode eatry by K e lt Picreon, of Plymouth, whkh w m j t j g d beet aI the M te thaa 4Meatrica received. The o rtn a li' letter* to Saata Qaaa aad the lafonnatioa on the wiaaero of the eoatept i'/y appear h today's Chrietmae CheckMet epecial eectioa. f e >t\ > X » > ,\\Y\V « i \ The tastethat’s lmmm SAVE Every Thursday CATERING S A V E 5 5 * discount on 1 0 % with this • 3 pcs. Chicken 4 barrels & up coupon • Cole Slaw • Mashed potatoes & gravy J 21 piece barrel ! • 2 biscuits discount on Reg. $2.29 i Plymouth j Thursdays 12 barrels & up | * J i store only j j Expires 1/1/80 j eQianki for the goodness of w n ovs % ec//c?e 1122 W. Am Artor Rd. ■m iem AiHAAiiflea PROPRIETOR PiyMontfc 453-6767 FX1GD C 9U G K E N J o e L m g k a b e l V^.VVT.».?,T^>V.f.T;T.T.TT.t.l.t.rt.»t'7 »f I H TTI » 7 r>*.y.rr.T.nrf. t>* PG. 3 .:...< BY PATRICIA BARTOLD for an informal workshop on Monday, It was a confusing vote, said Carolyn Elaine Kirchgatter moved to petition the ^ ; The Plymouth-' Canton Board of Dec. -

Finding Aid Template

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Corky Steiner Kenner History Collection Finding Aid to the Corky Steiner Kenner History Collection, 1947-1960, 2015 Summary Information Title: Corky Steiner Kenner history collection Creator: Corky Steiner and Joseph L. Steiner (primary) ID: 115.4174 Date: 1947-2015 (inclusive); 1956-1960 (bulk) Extent: 0.75 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are in English. Abstract: The Corky Steiner Kenner history collection is a compilation of advertisements, instruction manuals, ledgers, financial reports, business letters, journal articles, photographs, DVDs, and other documentation relating to Kenner Products during the 1950s and 1960s. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, he has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The Corky Steiner Kenner history collection was donated to The Strong in October 2015 as a gift from Corky Steiner. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 115.4174. The materials were received from Corky Steiner, son of Kenner co-founder and Easy-Bake Oven co-creator Joseph L. Steiner, in one box, along with a donation of Kenner trade catalogs and sell sheets. -

Cnldoi

^ V 3 -4 - FRIDAY, DECEMBER 18j 1970 PAGE THIRTY-TWO f Averapre Dafly Net Press Run iMancIiwtpr lEwnttig U m lii The Weather For Hie Wedi Boded November 14, ISTO Partial clearing, colder late tonighl after earlier abower pos- ; low in 20a. Sundax Lowest 16,080 S windy, cold, chance of V fliu rie s ; high in 80a. Extra s in Caldor’ s Prices ancheater— A City of Village Charm VOL. LXXXX, NO. 68 O n (EIGHTEEN PAGES—TV SECTION) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, DECEMBER 19, 4970 (Classified Advertising on Page 16) PRICE TEN CXNTS Fam ous \, Cnldoi N am e ' T o y s! Senate Rejects Polish Shipyards OPEN EXTRA LATE EVERY NIGHT! Enemy Attacks Mark Rw* < ■ — SST Debate Halt .............. : Echo with Gunfire _ ____ I By WALTER R. MEABS AaaocUted Frees Writer By NICHOLAS ULUTOS Radio Warsaw said the Polish WASHINGTON (A P)— The Senate rejected today an news agency PAP reported that WARSAW (AP) — After Quell attempt to halt delate bn a money bill containing funds ‘‘calm prevailed in the whole of [•Hot Curve Action ing mobs with rifle fire in the V iet W ar Anniversary •Hide and Seek the triple cities” today, with for the controversial supersonic transport. nation’s biggest shipyards, po- Set by Mattel House and Senate leaders met meanwhile to review a Uce and troops in Poland hive - by Ideal series of bills blocking. congressionaLadjournment. By GEORGE E8PEB A twoAhirds vote w aa-neces--------------------------------:_____ _____ Associated Press Writer saiy to secure cloture—and thus ate. northS^ citi^ ^ otln r^ ejr^ ™ "*^ ;!.^ *Dual Lane Rod' limit debate—on the Depart SAIGON (AP) — The I b oBark & Bite That would scrap a bill pend* edly spread to a fifth city Pri- ro^t^^rants Viet Ckinfir marked the 24th M onopoly S.T.A.R. -

ON NOVEMBER 30, 1928, a New Company Was Listed on the New York Stock Exchange

ON NOVEMBER 30, 1928, a new company was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Formed through the merger of several regional milling companies, General Mills would grow to become one of the largest food companies in the world. To mark that 75th anniversary, this book celebrates 75 years of innovation, invention, food and fun – both inside and outside the kitchen – in America and around the world. PROLOGUE 1 PROLOGUE It would be difficult to capture our rich history in a thousand pages. There are simply too many stories to tell. But this opportunity only comes once – and we couldn’t let it pass. On the 75th anniversary of the creation of General Mills – in our 137th year as a company – we wanted to pause to commemorate at least some of the historical highlights of a great American company. But where to start? With the creation of General Mills in 1928? Or at the beginning, on the banks of the Mississippi River in 1866? And what of the many companies with which General Mills has been intertwined? What of Pillsbury and Green Giant? What of Kenner and Parker Brothers, Red Lobster and Burger King? What of the products we invented together and the brands we built together? It was simple really. Pillsbury’s history is our history. Green Giant, Old El Paso, Colombo and Häagen-Dazs are here – alive within General Mills. Of the rest we chose to include a little of each, because they too are a part of us. And while we take no credit for the success they enjoy today, we are proud to have shared the same path for at least part of our shared history. -

View and Expert Focus Group 25

i WHAT DID YOU DO TO MY BRAND? THE MODERATING EFFECT OF BRAND NOSTALGIA ON CONSUMER RESPONSES TO CHANGED BRANDS A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Business in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Alison B. Shields April 2012 ii iii Abstract Marketers often make changes to brands to make the brand seem current or exciting. Some updates are successful while others are spectacular failures. This dissertation establishes a connection between consumer acceptance or rejection of updated brands and the consumer’s reported brand nostalgia. In this dissertation, I refine the current marketing definitions of nostalgia to develop a more specific construct of brand nostalgia, develop a scale to measure the construct of brand nostalgia, examine the differences between schemas for nostalgic brands and non-nostalgic brands, and show that consumers’ affective and attitudinal responses to changes in a brand are moderated by brand nostalgia. Nostalgia has been defined as “a positively toned evocation of a lived past” (Davis 1979), and “a fondness for possessions and activities associated with days of yore” (Holbrook 1993). Consumers have been observed to engage in nostalgic behaviors, from re-watching favorite old movies (Holbrook, 1993) to reminiscing about favorite cars from their youth (Brown, Kozinets and Sherry 2003) to consuming specific foods as a way to reconnect with the past (Loveland, Smeesters and Mandel, 2010). Consumers have also reported nostalgic feelings for particular brands or items (Holbrook and Schindler 2003). When individuals recall nostalgic memories, they recall affect and brand information stored in their schema for the target brand (Collins and Loftus 1975). -

MOSAIC Life Engagement Calendar

MOSAIC Life Engagement Calendar November 4 - 10, 2019 4 Monday 5 Tuesday 6 Wednesday 7 Thursday 8 Friday 9 Saturday 10 Sunday Alzheimer's National Bittersweet National Model Awareness Election Day National Nachos Day Chocolate with Domino Day World Science Day Railroad Month Month Almonds Day Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Devotions Devotions Devotions Devotions Devotions Devotions Church Time Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Exercise Exercise Exercise current events Exercise Exercise Great States game Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Spirograph card Just Say N game Mock Election daily stretch pass a story dominos cup stacking making golf game QOL Profile Nacho making Bowling nails Pool Noodle Ball crossword puzzle Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat tic tac toe Balloon tree art Hugger Mugger game Kitchen Creations Happy Hour cards ball bounce to cups Reminisce-Miltary Supper Supper Supper Supper Supper Supper Supper Purposeful Destination Basketball Parachhute lawn darts domino game Family Movie Jenga Walk Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Snack-n-Chat Using our MOSAIC programming, in addition to these scheduled activities, you will see us engaging residents in one-on-one activities such as Reminisce Baskets, hand massages, manicures and person-centered conversations throughout the day. We will also be focusing on creating small group activities highlighting common likes and hobbies. -

Hasbro, Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant, As Specified in Its Charter)

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 Form 10-K ፤ Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 26, 2004 Commission file number 1-6682 Hasbro, Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant, As Specified in its Charter) Rhode Island 05-0155090 (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1027 Newport Avenue, 02862 Pawtucket, Rhode Island (Zip Code) (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (401) 431-8697 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock New York Stock Exchange Preference Share Purchase Rights New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes or No អ. Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. ፤ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an accelerated filer (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Act). -

2020 BR GOH Gift List

F L O R I D A P O W E R A N D L I G H T S P O N S O R S GIFT OF HOPE 2 0 2 0 T O Y D R I V E Visit 4KIDS.us/GiftofHope to shop and ship any of these items directly through Amazon. B A B I E S T O D D L E R S 2 - 4 G I R L S 5 - 1 2 Baby Einstein Music Explorer Paw Patrol Pirate Vehicles Barbies Baby Einstein Discover & Play Piano Paw Patrol Walkie Talkies Barbie Two Story House Baby Einstein Octopus Orchestra Paw Patrol Adventure Bay Railway Barbie Dreamtopia Sparkle Lights Mermaid Bright Starts Safari Beats Doc McStuffins Get Better Baby CeCe Barbie Doggy Daycare Doll & Pets Fisher Price Kick & Play Piano Doc McStuffins Toy Hospital Minnie Motor Makeover Salon Infantino Tummy Time Play Mat Bright Stars Go Grippers Cars Minnie’s Happy Helpers Bag Set Bright Starts Tummy Time Prop & Play Little People Cinderella Coach furReal Rock-A-Too The Show Bird Infantino Play Time Pal VTech Go! Go! Smart Wheels Race & Play Adventure Park Toy Kitchen Supplies Fisher Price Baby’s Bouncer Little People Swing & Share Treehouse Cutetitos Mystery Surprise Baby Einstein Sea & Discover Door Jumper Little People Songs & Sounds Camper Disney Princess Dress Up Outfit Infantino Up Up & Away Doorway Jumper Fisher Price Say Please Snack Set Shopkins Swaddle Me Slumber Buddies Elephant Fisher Price Laugh & Learn Smart Stages Tablet Barbie Crimp & Color My Baby Sound Spay Portable Fisher Price Learn with Me Zebra Walker Hairdorables Swaddle Me Mommie’s Melodies Fisher Price Soothe n' Snuggle Otter Toy Story Toys (Not Forky Plush) My Baby Sound Spa Lullaby Little -

2020 TC GOH Gift List Digital

GIFT OF HOPE 2 0 2 0 T O Y D R I V E Visit 4KIDS.us/GiftofHope to shop and ship any of these items directly through Amazon. B A B I E S T O D D L E R S 2 - 4 G I R L S 5 - 1 2 Baby Einstein Music Explorer Paw Patrol Pirate Vehicles Barbies Baby Einstein Discover & Play Piano Paw Patrol Walkie Talkies Barbie Two Story House Baby Einstein Octopus Orchestra Paw Patrol Adventure Bay Railway Barbie Dreamtopia Sparkle Lights Mermaid Bright Starts Safari Beats Doc McStuffins Get Better Baby CeCe Barbie Doggy Daycare Doll & Pets Fisher Price Kick & Play Piano Doc McStuffins Toy Hospital Minnie Motor Makeover Salon Infantino Tummy Time Play Mat Bright Stars Go Grippers Cars Minnie’s Happy Helpers Bag Set Bright Starts Tummy Time Prop & Play Little People Cinderella Coach furReal Rock-A-Too The Show Bird Infantino Play Time Pal VTech Go! Go! Smart Wheels Race & Play Adventure Park Toy Kitchen Supplies Fisher Price Baby’s Bouncer Little People Swing & Share Treehouse Cutetitos Mystery Surprise Baby Einstein Sea & Discover Door Jumper Little People Songs & Sounds Camper Disney Princess Dress Up Outfit Infantino Up Up & Away Doorway Jumper Fisher Price Say Please Snack Set Shopkins Swaddle Me Slumber Buddies Elephant Fisher Price Laugh & Learn Smart Stages Tablet Barbie Crimp & Color My Baby Sound Spay Portable Fisher Price Learn with Me Zebra Walker Hairdorables Swaddle Me Mommie’s Melodies Fisher Price Soothe n' Snuggle Otter Toy Story Toys (Not Forky Plush) My Baby Sound Spa Lullaby Little People Music Parade Ride On Tomagotchi Virtual Pets Jumbo -

Securities and Exchange Commission

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 Form 10-K Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 25, 1994 Commission file number 1-6682 ----------------- ------ Hasbro, Inc. -------------------- (Name of registrant) Rhode Island 05-0155090 ------------------------ ------------------- (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1027 Newport Avenue, Pawtucket, Rhode Island 02861 -------------------------------------------------- (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (401) 431-8697 -------------- Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class on which registered ------------------- --------------------- Common Stock American Stock Exchange Preference Share Purchase Rights American Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes[X] or No[ ]. Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant's knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part II of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. [X] The aggregate market value of the voting stock held by non-affiliates of the registrant computed by reference to the price at which the stock was sold on March 16, 1995 was $2,519,054,620. -

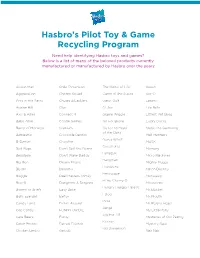

Hasbro's Pilot Toy & Game Recycling Program

Hasbro’s Pilot Toy & Game Recycling Program Need help identifying Hasbro toys and games? Below is a list of many of the beloved products currently manufactured or manufactured by Hasbro over the years: Action Man Child Dimension The Game of Life Koosh Aggravation Chomp Squad Game of the States Kre-O Ants in the Pants Chutes & Ladders Gator Golf Larami Avalon Hill Clue GI Joe Lite Brite Axis & Allies Connect 4 Giggle Wiggle Littlest Pet Shop Baby Alive Cootie Games Go For Broke Lucky Ducks Barrel of Monkeys Cranium Go to the Head Magic the Gathering of the Class Battleship Crocodile Dentist Mall Madness Guess Who? B-Daman Crossfire MASK Guesstures Bed Bugs Don’t Spill the Beans Memory Hanazuki Beyblade Don’t Wake Daddy Micro Machines Hangman Big Ben Dream Phone Mighty Muggs Headache Blythe Dropmix Milton Bradley Heroscape Boggle Duel Masters (Xm2) Monopoly Hi Ho Cherry-O Bop-It Dungeons & Dragons Mousetrap Hungry Hungry Hippos Boxers or Briefs Easy Bake Mr. Bucket i-Dog Bulls-Eye Ball Elefun Mr. Mouth India Candy Land Fishin’ Around Mr. Potato Head Jenga Cap Candy FUNNY OR DIE My Little Pony Joy For All Care Bears Furby Mysteries of Old Peking Kenner Catch Phrase Furreal Friends Mystery Date Kid Dimension Chicken Limbo Galoob Nak Nak Nerf Pound Puppies Stay Alive No Brainer Puzz 3D Strawberry Shortcake Oddzon Products Rack-O Stretch Armstrong Operation Risk Subbuteo Ouija Rook Super Soaker Outburst Scattergories Taboo Parcheesi Scrabble Taste Game Parker Brothers Scruples Tiger Electronics Pay Day Shoezies Tonka Perfection Simon Transformers Pictionary Sindy Trivial Pursuit Picture Perfect Skip-It Trouble Pictureka Sorry Twister Pie Face Speak Out Visionaries Play-Doh Spirograph Yahtzee Playskool Splat!.