School Broadcasting Organization: an Analysis of Structure and Functions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morrie Gelman Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8959p15 No online items Morrie Gelman papers, ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Finding aid prepared by Jennie Myers, Sarah Sherman, and Norma Vega with assistance from Julie Graham, 2005-2006; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Morrie Gelman papers, ca. PASC 292 1 1970s-ca. 1996 Title: Morrie Gelman papers Collection number: PASC 292 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 80.0 linear ft.(173 boxes and 2 flat boxes ) Date (inclusive): ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Abstract: Morrie Gelman worked as a reporter and editor for over 40 years for companies including the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Post, Newsday, Broadcasting (now Broadcasting & Cable) magazine, Madison Avenue, Advertising Age, Electronic Media (now TV Week), and Daily Variety. The collection consists of writings, research files, and promotional and publicity material related to Gelman's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Gelman, Morrie Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

The Early Cold

1 Crypto-Convergence, Media, and the Cold War: the Early Globalization of Television Networks in the 1950s Media In Transitions Conference, MIT, May 2002 James Schwoch Northwestern University Center for International and Comparative Studies 618 Garrett Place Evanston IL 60201-4135 USA [email protected] About the Author: James Schwoch is an Associate Professor at Northwestern University, where he works in the Center for International and Comparative Studies and the Department of Communication Studies. Currently the 2001-02 Van Zelst Professor of Communication, Schwoch is working on a book-length study tentatively titled Cold Bandwidth: Television, Telecommunications, and American Diplomacy’s Quest for East-West Security. His work has been funded by, among others, the Center for Strategic and International Studies; the Ford Foundation; the Fulbright Commission (Germany); the National Endowment for the Humanities; and the National Science Foundation. Copyright ã 2002 James Schwoch. All rights reserved by the author. Citation, circulation, and comments from readers are welcome. 2 Crypto-Convergence, Media, and the Cold War: the Early Globalization of Television Networks in the 1950s PLATE 01: The UNITEL Global TV---Telecommunication Network Plan, 19521 The concept of global television networks is usually considered to be a recent phenomenon, emergent in the last years of the Cold War. Seen as an outgrowth of the expansion of the communications satellite, the worldwide plunging costs of television set ownership, the recent global cross-investments involving media industries, and the collapse of the superpower conflict, global television networks represent, for most observers, a relatively new idea. 1 “The UNITEL Relay Network Plan,” October 1952, Jackson, C.D.: Records, 1953-54 (hereafter C. -

Networking and 67 Expressed Degrees of Interest in Participation. a Sample

DOCUMENT RF:sumn ED 025 147 EM 000 326 By- McKenzie. Betty. Ed; And Others 17-21. 1960). Live Radio Networking for EducationalStations. NAEB Seminar (University of Wisconsin. July National Association of Educational Broadcasters,Washington, D.C. Pub Date [601 Note- 114p. Available from- The National Association of EducationalBroadcasters. Urbana. Ill. ($2.00). EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$5.80 Descriptors-Broadcast Industry. Conference Reports.*Educational Radio.*Feasibility Studies. Financial Needs, Intercommunication, National Organizations.*Networks, News Media Programing,*Radio. Radio Technology, Regional Planning Identifiers- NAEB, *National Association Of EducationalBroadcasters A National Association of EducationalBroadcasters (NAEB) seminarreviewed the development of regional live educationalnetworking and the prospectof a national network to broadcast programs of educational,cultural, and informationalinterest. Of the 137 operating NAEB radio stations,contributing to the insufficient news communication resources of the nation,73 responded to a questionnaire onlive networking and 67 expressed degreesof interestinparticipation. A sample broadcasting schedule was based on the assumptionsof an eight hour broadcast day, a general listening audience, andlive transmission. Some ofthe advantages of such a network, programed on a mutualbasis with plans for a modifiedround-robin service, would be improvededucational programing, widespreadavailability, and reduction of station operating costs. Using13 NAEB stations as a round-robinbasic network, the remaining 39 could be fed on a one-wayline at a minimum wireline cost of $8569 per month; the equivalent costfor the complete network wouldbe $17,585. As the national network develops throughinterconnection of regionalnetworks and additionof long-haultelephonecircuits,anationalheadquartersshould be established. The report covers discussiongenerated by each planningdivision in addition to regional group reports fromeducational radio stations. -

Chinese Co: On

*r* ' • ■■ i S' : - f r - iS >* ' • ■ ..' ' ' f- ■ - - ■ ^ ' ■ -■W B. ■ 'k WEDMESeiAY, JAmiART I. 1 M \ h '/ L\\ \jyfL -»* IRatt^Ir»atnr Utmtittff IjgriJii ? The Wsstksr Average Dally Nat Praas Rua rerMBBl Bf O. S, WBalhar aei up rw Maui Bf D*whw, istt ’• riu* BMtl bM*«inlna «.sM*r tkit 9,664 xf(«ri<a(i««: fair *wr«i.tirr tnaighk aMi Fri-lry. CUy of Village Charm (SIXTEEN PAGES) PRICE FOUR CENTS (CtaBBlIM ASvertMag an rsfa 14) MANCHESTER, THURSDAY, JANUARY 6, 1949’ \ VOL. LXVIU., Jio* W \ • - GtaVaadBoyk* DRESSES . Coat and L eg g ^ Sets SoJ^e of Blizzard : Prertdeht Addresses Congress Chinese Co: G W Sets 1 yr. to 6x—B oysN ^ 8 to 8 jwu, \ r*iOiie" CircNip at ^ $5*00 Reg. $9.58 Values . ..V . .Nowr $ ft.0 0 V ictiMs Rescued; V * One Group at $6.00 Reg. $15.98 and $16.98 " / V a lu ea . *..i.. P low $13.00 Aid Sent Others V Oto - Group at , $8.00 on Reg. $18.98 and $19.98 B ig g e s t E vacu a- Bill to Boost ^ ' V a l n e i .................... llfo w $16*00 b y R e d * One Gro>up at » 9 tio n ' Turn Deaf Ear to Na C ross •’W h ic h Droppeil Safely Reg. $22.98 ValuM ,.. Steel Output Council Order tionalist Peace Pleas * One Group at $11 1^ P ic k s u t 6 0 0 * " 'w . ■». 'i $19.00 Eneircletl ArMies gl H a l f , S ta rved R e fu - To Cease Fire Looming Now . -

Proceedings of the American Association for Public Opinion Research

Proceedings of the American Association for Public Opinion Research At the Third International Conference on Public Downloaded from Opinion Research, Eagles Mere, Pennsylvania, September 12-15, 1948 FOREWORD http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/ The third international conference on public opinion research marked the establishment on a permanent basis of two professional societies, one domestic, one international, which had their inception at the first conference at Central City, Colorado, in the summer of 1946. This report of the pro- ceedings of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, severely condensed though it be, documents the progress that has been made during the two years since the first of these meetings was held. Even more than at AAPOR Member Access on March 8, 2016 Williamstown, Eagles Merc showed a responsibleness of mind in appraising problems, methods, and techniques, and in accepting the obligations of com- petence that rest upon professionals whether they arc serving private clients or the public and whether they are interested in the development of abstract knowledge or in practical administrative service. Only such conferences in which theorists, technologists, and practitioners consider their problems with complete frankness and severely critical thoughtfulness will enable any one of these groups to make its maximum contribution. CLYDE W. HART President, American Association for Public Opinion Research, 1947-48 Editorial Note: The following reports repre- many other* who assisted in the preparation sent 1 rather severe condensation, necessitated of this record. For the most part, speakers' by budgetary considerations, of the full pro- remarks are presented in direct discourse, ceeding, of the conference- All remark, have rlther than indirect> j,, order to ^ been compressed considerably, and it has un- , _ .. -

Latin America: National Security Files, 1961-1963

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY NATIONAL SECURITY FILES LATIN AMERICA: NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961-1963 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS Of AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of The John F. Kennedy National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring LATIN AMERICA National Security Files, 1961-1963 Microfilmed from the holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Project Coordinator and Guide compiled by Robert E. Lester A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files. Latin America [microform] : national security files, 1961-1963 : microfilmed from the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Robert E. Lester. ISBN 1-55655-009-X (microfilm) ISBN 1-55655-010-3 (printed guide) 1. Latin America-Foreign relations-United States-Sources. 2. United States-Foreign relations-Latin America-Sources. 3. John F. Kennedy Library-Archives. I. Lester, Robert. II. John F. Kennedy Library. III. University Publications of America (Firm) [F1418] 327.7308-dc20 91-31371 CIP Copyright ® 1987 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-010-3. TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction•The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: "Country Files," 1961-1963 v Introduction•The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: Latin America, 1961-1963 ix Scope and Content Note xi Source Note xn Editorial Note x¡¡ Security Classifications xiv Key to Names xv Abbreviations List xxvii Reel Index Reels 1-2 Brazil 1 ReelS Brazil cont 57 British Guiana 77 Chile 83 Reels 4-8 Cuba 85 Reel 9 Cuba cont '. -

DOC-308696A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission 29th Annual Report For the Fiscal Year 1963 With summary and notation of sUbsequent important developments UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. WASHINGTON. 1963 For lale by the Superintendent of Documenll, U.S. Government Printing Office W(l$hington, D.C., 20402 - Price SO centl COMMISSIONERS Members of the Federal Communicotions Commission (As of June 30, 1963) E. WILLIAM Hr!NRY, Ohai'NlUl1/. (Term expires June 30, 1969) ROSEL H. HYDE (T~rm expires June 30, 1966) ROBERT T. BARTLEY (Term expires June SQ, 1965) RoBERf E. LEE (Term expires June 30, 1967) FREDERICK tV. FORD (Term expires June 30, 1964) KENNETH A. Cox (Term expires June 30, 1970) LEE LOEVINGER (Term expires June 30, 1968) A list ot present and past Commissioners appears on page n. n LmER OF TRANSMInAL FEDERAL CoM1>IDIDCATIONS COMMISSION, W Il8hington, D.O., f!(}oo.li To the Oongress of the United States, Transmitted herewith is the 29th Annual Report of the Federal CommWlications Commission. The report furnishes information required by section 4(k) of the CommWlications Act of 1934, as amended, with respect to the fiscal year 1963 and notes subsequent important happenings up to the time of going to press. This updating is essential for more current appraisal of the rapid developments in space and national defense communication; progress in assisting UHF television generally and educational TV in par ticular; problems of AM broadcast congestion and growing pains of FM; continued stress by the Commission on public-service obligations of broadcasters; unceasing growth and attendant complications in the many nonbroadcast radio services; automation and other mod ernization of telegraph and telephone facilities; and the never-ending search for additional space and frequency-usage economies to ac commodate new and expanding radio services. -

University Microfilms International 300 N ZEE B ROAD

INFORMATION TO USERS This produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the I"*1** advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document ** been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material “ ^ tte d . The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand ra,rtS p or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Pagefs)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round Mack mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming >t the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1948-09-10

• The Weather TocIay . Judge Does Fine Work Fair with little change in temperature to P BTLADELPHIA (JP) - Mal'l trate Jaeob Dor.1e ""t C' lalmlnl' a record but he h d a r1'hl fine day 10 ceo· day. Partly cloudy and warmer tomorrow. tnJ police court yesterday. Yesterda y'S high was 77 and the mercury Alter four li nd one-bllif holll'S of hearlnp, the mu- _. !Strate announced the follow;nr score: owaJll dropped to a chilly 43 at about 3 a. m. yes Cases disposed of: 900. terday for the low temperature. CoUected In fines: 4,500 - practically a record. Eat. 186S-Vol. SO, No. 294-UP, AP New. and W irepholo Iowa City, Iowa, Friday, Sept. 10, 1948 Five Cents New Election, AFL Union To Support Dewey Reveal Elpori (ailed (or by Irregularities Senator, Hear Tales ADe Gaullist Of Forgery, Bungling WAS) lING TON (JP)-Astonisb French Workers Riot ed seMtors dug up th assorted As Queuille Steps In facts yesterday about this govern ment's export lice~ program: PARIS (JP)-An official spokes 1. Nail Z and one-ball and :I man for Gen. Charles De Gaulle inches long-badly needed to build called last night lor new national h(.lnes-were xported last year French elections. as .. h tacks." Tijis was the timt time De 2. A woman I'overrunent clerk Gaulle had intervened during a issued permits to export more cabinet crisis. than two million pounds of lard Jacques Soustelle, secretary during a period wh n the quota general of De Gaulle's French was 199.000 pounds. -

Fundamentals of Television Systems. By- Kessler, Willz:.M J

REPOR TRESUMES ED 0200)I I. -7; EM DOD 232 FUNDAMENTALS OF TELEVISION SYSTEMS. BY- KESSLER, WILLZ:.M J. NATIONAL ASSN. OF EDUCATIONAL BROADCASTERS PUB DATE FEB 68 EORS PRICEMF-$0.50 HC-$3.28 80P. neno-linvnvel.oln ..... IL- ut nt #tlt AIr_:".nrAte teE 6".111 imm^ArteAeT ,),Irnier I WV. .42 n'iimEtwIra %swop re aela.m.rvilis... I1.bb, AVaV1, TELEVISION COMIAUNICATION SATELLITES, *RADIO TECHNOLOGY, *ELECTRONIC EQUIPMENT, PRODUCTION TECHNIQUES, DESIGNED FOR A READER WITHOUT SPECIAL TECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE, THIS ILLUSTRATED RESOURCE PAPER EXPLAINS THE COMPONENTS OF A TELEVISION SYSTEM AND RELATES THEM TO THE COMPLETE SYSTEM. SUBJECTS DISCUSSED ARE THE FOLLOWING--STUDIO ORGANIZATION AND COMPATIBLE COLOR TELEVISION PRINCIPLES, WIRED AND RADIO TRANSMISSION SYSTEMS, DIRECT VIEW AND PROJECTION DISPLAY OF TELEVISION IMAGES, AND PHOTOGRAPHIC, DIRECT VIDEO, AND ELECTRON BEAM RECORDING. RADIO TRANSMISSION SYSTEMS DISCUSSED ARE VHF-UHF BROADCASTING AND TRANSLATORS, AIRBORNE AND STAELLITE TRANSMISSION, LASER TRANSMISSION, POINT-TO-POINT AND SATELLITE TRANSMISSION, LASER TRANSMISSION, POINT-TO-POINT FIXED SERVICE. APPENDICES INCLUDE A GLOSSARY AND A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY. (BB) Television Systems: '16'..."1C U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE Of EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR 0116FilIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE Of EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. FUNDAMENTALS OF TELEVISION SYSTEMS . by William J. Kessler, P. E. W. J. Kessler Associates Consulting Telecommunications Engineers Gainesville, Florida February, 1968 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 444 Foreword 114 Introduction iv re Fundamentals of Television 1 The Studio Origination Facility 6 Compatible Color Television Principles 12 Transmission of Television Signals 16 Wired Systems 17 Radio Transmission Systems 22 1. -

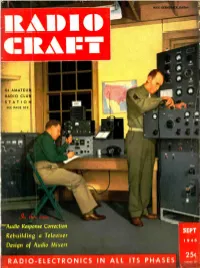

Radio-Electronics in All Its Phases Ada 30

Editor RA I O -1Motap, GI AMATEU RADIO CLU STATIO SEE PAGE 828 Audio Response Correction SEPT Rebuilding a Televiser 1 9 4 6 Design of Audio Mixers RADIO-ELECTRONICS IN ALL ITS PHASES ADA 30. PANORAMIC RECEPTION attends the opening of the 20 and 40 meter bands When the 20 and 40 meter bonds reopened for amateur communication with all the excite- ment and ceremony that usually accompanies a " ight," a Panadaptor sat in on the fun. Below is an account, with illustrations, of the act 'ty that took place before, during and after that long- awaited ha occasion. (As Viewed by W LNP) 12 MIDNIGHT! All aetivlt, 'Ohio the 2:00 -2:30 A.M.! Signals appeared on the 3i0STAGE. the S Broadcasting I l Bri h Corn. band comet]. The stations e le outside band. Patterns of deflections showed that pony and Spanish w station were still to Point remained on. these only carriers. and not actual seens n and heard on the a0 meter band. thmm antrat Ions. Their signals occupied the center of the On the edge of the screen. but eut. side of the band, were few w and phone stations 4 And the official message from the A.M.! 405.4:30 A.M.! Wlthi few minutes .5 A.M.! The number of stations en the of the official station of ARAL. WIAW, announcement.. ent. abc 1lteen stations as growing. And activity on the 40 'taunted to 40 were on . all amateurs that the 20 and air. arl. rns: W2LNP, irtew band appeared to be normal for the meter bands were again their property. -

Federal Communications Commission

SIXTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION FISCAL YEAR ENqtO JUNE 30, 1950 (With notation al sUb;~e~~portantdevelopments) JUNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE· WASHINGTON. 1951 For sal. by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. Price 40 cents COMMISSIONERS MEMBERS OF THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION (as of December 1, 1950) CHAIRMAN WAYNEOoy (Term expires June 30,1951) PAUL A. WALKER ROBERT F. JONES (Term expires June 30.1953) (Term expires J'une 80,1954) ROSEL H. HYDE GEORGE E. STERLING (Term expires June 30,1952) (Term expires June 30,1957) EDWARD M. WEBSTER FRIEDA B. HENNOCK (Term exnires June 30, 1956) (Term expires June 30. 1955) n LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION, Washington 25, D.O., December 29, 195(J. 1'0 the Oongress 0/ the UnitedState8: The sixteenth annual report of the Federal Communications Com mission is submitted herewith in compliance with section 4 (k) of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended. By custom, this report deals primarily with Commission activities for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1950. However, telecommunica tious is such a fast-moving subject that it has been found appropriate to include in tlie introductory summary brief reference to subsequent events up to the time of going to press. The attention of the Congress is invited, in particular, to the little publicized yet highly important developments in the nonbroadcast field. Here new and augmented services have a material public impact in utilizing radio for the protection of life and property, as adjuncts to commerce and industry, and in furthering common car rier telephone and telegraph service.