Politics of Script: Tiie Case of Konkani (1961 - 1992)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government of Goa Directorate of Health

GOVERNMENT OF GOA DIRECTORATE OF HEALTH SERVICES INSTITUTE OF NURSING EDUCATION BAMBOLIM – GOA 403 202 POST BASIC DIPLOMA IN NURSING PROSPECTUS 2020-2021 NO. _______________ Rs. 1000/- INSTITUTE OF NURSING EDUCATION BAMBOLIM-GOA INDEX Sr. No. PART I Pg. No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Philosophy 1 3. Objective 1 4. Ordinance 1 5. Scheme of hours 1 6. Scheme of examination 2 7. Fees 2 8. Bond 2 9. Anti Ragging 3 10. Miscellaneous 3 PART II 1. Eligibility for admission 4 2. Application for admission 4 3. Certificates required 4 4. Allocation of seats 6 5. Guidelines for selection 6 6. Notification of eligibility, selected and wait-listed candidates 6 7. Cancellation of admission. 6 8. Refund of fees 7 9. Proforma for certificates 8-11 10. Application Form 11. Schedule of admission process PART – I 1. Introduction The Institute of Nursing Education, Bambolim, Goa recognized by the Indian Nursing Council functions as an independent unit under the Directorate of Health Services, Government of Goa; with the introduction of the Post Basic Diploma in Nursing Programs the Institute will be responsible for conducting five nursing educational programs namely: 1. Auxiliary Nurse Midwife program 2. B.Sc. Nursing program. 3. M.Sc. Nursing program 4. Post Basic Diploma in Neonatology Nursing 5. Post Basic Diploma in Cardio thoracic Nursing 2. Philosophy We at the Institute of Nursing Education believe that: * The core of nursing is directed towards caring for the individual (sick or well)/family and community, therefore the nursing education programs run in at the Institute of Nursing Education primarily focus on meeting the health needs of the individual/family/community. -

Journal of Social and Economic Development

Journal of Social and Economic Development Vol. 4 No.2 July-December 2002 Spatial Poverty Traps in Rural India: An Exploratory Analysis of the Nature of the Causes Time and Cost Overruns of the Power Projects in Kerala Economic and Environmental Status of Drinking Water Provision in Rural India The Politics of Minority Languages: Some Reflections on the Maithili Language Movement Primary Education and Language in Goa: Colonial Legacy and Post-Colonial Conflicts Inequality and Relative Poverty Book Reviews INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE BANGALORE JOURNAL OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT (Published biannually in January and July) Institute for Social and Economic Change Bangalore–560 072, India Editor: M. Govinda Rao Managing Editor: G. K. Karanth Associate Editor: Anil Mascarenhas Editorial Advisory Board Isher Judge Ahluwalia (Delhi) J. B. Opschoor (The Hague) Abdul Aziz (Bangalore) Narendar Pani (Bangalore) P. R. Brahmananda (Bangalore) B. Surendra Rao (Mangalore) Simon R. Charsley (Glasgow) V. M. Rao (Bangalore) Dipankar Gupta (Delhi) U. Sankar (Chennai) G. Haragopal (Hyderabad) A. S. Seetharamu (Bangalore) Yujiro Hayami (Tokyo) Gita Sen (Bangalore) James Manor (Brighton) K. K. Subrahmanian Joan Mencher (New York) (Thiruvananthapuram) M. R. Narayana (Bangalore) A. Vaidyanathan (Thiruvananthapuram) DTP: B. Akila Aims and Scope The Journal provides a forum for in-depth analysis of problems of social, economic, political, institutional, cultural and environmental transformation taking place in the world today, particularly in developing countries. It welcomes articles with rigorous reasoning, supported by proper documentation. Articles, including field-based ones, are expected to have a theoretical and/or historical perspective. The Journal would particularly encourage inter-disciplinary articles that are accessible to a wider group of social scientists and policy makers, in addition to articles specific to particular social sciences. -

Foreign Affairs Record VOL XXXIX NO 1 January, 1993

1993 January Volume No XXXIX NO 1 1995 CONTENTS Foreign Affairs Record VOL XXXIX NO 1 January, 1993 CONTENTS BHUTAN King of Bhutan, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck Holds Talks with Indian Leaders 1 Indo-Bhutan Talks 1 CANADA Shrimati Sahi Calls for Indo-Canadian Industrial Cooperation 2 Canadian Parliamentary Delegation Meets the President 3 CHILE India, Chile Sign Cultural Pact 4 IRAN Protection of Iranian and other Foreign Nationals 4 MALDIVES Shri Eduardo Faleiro, Minister of State for External Affairs Visits Maldives 4 MAURITIUS Indo-Mauritius Joint Venture 5 MISCELLANEOUS New Welfare Scheme for Handloom Weavers - Project Package Scheme Extended 5 START-II Treaty 6 OIC Bureau Meeting at Dakar 7 Training of Foreign Diplomats by India under the ITEC Programme and the Africa Fund 7 Projecting India as a Safe and Exciting Destination - two day's Overseas Marketing Conference 8 Programme of Elimination of Child Labour Activities Launched 9 OFFICIAL SPOKESMAN'S STATEMENTS Move to Organise a March to Ayodhya by Some Bangladeshis 10 Expulsion of 418 Palestinians by Israel 10 Exchange of Lists of Nuclear Installations in India and Pakistan 10 Reduction in Staff-Strength by Pakistan High Commission 11 SAARC Summit at Dhaka 11 Organisation of Islamic Conference Meeting at Dakar 12 India's Reaction to OIC's Announcement 12 Prime Minister's Meeting with some Indian Heads of Missions from various Countries 12 Allied Air Strikes Against Iraq 12 Assumption of Charge by New External Affairs Minister and the MOS 13 Bangladesh Parliament Passes Resolution on Ayodhya 13 Meeting between the Indian Prime Minister and British Prime Minister 14 Indo-Russian Talks 15 Indo-Russian Talks on the Issue of Palestinian Deportees 16 PAKISTAN Joint Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs, Shri M. -

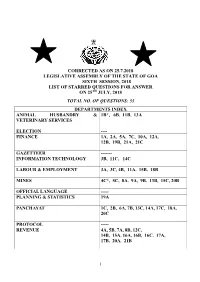

Corrected As on 25.7.2018 Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa Sixth Session, 2018 List of Starred Questions for Answer on 25Th July, 2018

CORRECTED AS ON 25.7.2018 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA SIXTH SESSION, 2018 LIST OF STARRED QUESTIONS FOR ANSWER ON 25TH JULY, 2018 TOTAL NO. OF QUESTIONS: 55 DEPARTMENTS INDEX ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & 1B*, 6B, 11B, 13A VETERINARY SERVICES ELECTION ---- FINANCE 1A, 2A, 5A, 7C, 10A, 12A, 12B, 19B, 21A, 21C GAZETTEER ------- INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 3B, 11C, 14C LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 3A, 3C, 4B, 11A, 15B, 18B MINES 4C*, 5C, 8A, 9A, 9B, 13B, 15C, 20B OFFICIAL LANGUAGE ----- PLANNING & STATISTICS 19A PANCHAYAT 1C, 2B, 6A, 7B, 13C, 14A, 17C, 18A, 20C PROTOCOL ----- REVENUE 4A, 5B, 7A, 8B, 12C, 14B, 15A, 16A, 16B, 16C, 17A, 17B, 20A, 21B 1 SL. MEMBER QUESTION DEPARTMENT NO. NOS 1A FINANCE 1. SHRI WILFRED D’SA 1B* ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & VETERINARY SERVICES 1C PANCHAYAT 2. SHRI FILIP NERI 2A FINANCE RODRIGUES 2B PANCHAYATI RAJ 3A LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 3. SHRI SUBHASH 3B I.T. SHIRODKAR 3C LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 4A REVENUE 4. SHRI PRASAD GAONKAR 4B LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 4C* MINES 5A FINANCE 5. SHRI LUIZINHO FALEIRO 5B REVENUE 5C MINES & GEOLOGY 6A PANCHAYATI RAJ 6. SHRI CHURCHILL ALEMAO 6B ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 7A REVENUE SHRI ALEIXO REGINALDO 7B PANCHAYAT 7. LOURENCO 7C FINANCE 8A MINES & GEOLOGY 8B REVENUE 8. SHRI CHANDRAKANT KAVALEKAR 9A MINES & GEOLOGY 9B MINES & GEOLOGY 9. SHRI DEEPAK PAUSKAR 10. SHRI GLENN SOUZA TICLO 10A FINANCE 11A LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 11. SHRI ANTONIO FERNANDES 11B ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 11C INFORMATION & TECHNOLOGY 2 12. SHRI NILESH CABRAL 12A FINANCE 12B FINANCE 12C REVENUE SHRI RAJESH PATNEKAR 13A ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 13 13B MINES 13C PANCHAYAT 14A PANCHAYAT 14 SHRI DAYANAND SOPTE 14B REVENUE 14C INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 15A REVENUE 15 SHRI RAVI NAIK 15B LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 15C MINES 16A REVENUE SHRI JOSE LUIS CARLOS 16B REVENUE 16 ALMEDA 16C REVENUE 17A REVENUE 17B REVENUE 17 SHRI FRANCISCO SILVEIRA 17C PANCHAYATI RAJ SHRI NILKANTH 18A PANCHAYATI RAJ 18 HALARNKAR 18B LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 19A PLANNING & STATISTIC SHRI PRATAPSINGH RANE 19 19B FINANCE 20A REVENUE 20B MINES & GEOLOGY 20 SHRI ISIDORE FERNANDES 20C PANCHAYATI RAJ 21A FINANCE 21B REVENUE 21. -

Carrying Capacity of Beaches of for Providing Shacks & Other Temporary Goa Seasonal Structures in Private Areas

Carrying Capacity of Beaches of for Providing Shacks & Other Temporary Goa Seasonal Structures in Private Areas Submitted to Government of Goa Prepared by NATIONAL CENTRE FOR SUSTAINABLE COASTAL MANAGEMENT Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change Government of India Carrying Capacity of Beaches of Goa for Providing Shacks & Other Temporary Seasonal Structures in Private Areas Foreword India is forging ahead with a high development agenda, especially along the long coastline, which inadvertently causes adverse impacts on the environment. Most of these activities are unplanned, leading to an imbalance in ecological sustainability. It is evident that developmental activities need to be regulated and managed, so that deterioration of the environment can either be minimized or avoided. This can be achieved by estimating the carrying capacity of a system that enables better planning for development, concurrently safeguarding ecological and environmental and social concerns. The State of Goa is one of world‟s most renowned tourism destinations with several natural beaches along its 105 km coastline, with a tourist footfall of over 50,00,000 tourists per year. Despite such heavy human pressure on a limited coastal scape, the Government of Goa has attempted to maintain the integrity of its beaches by regulation and management measures. However, a more systematic and scientific approach, was necessary to protect the ecological and environmental resources and to ensure livelihood sustainability. Based on such principles, the present study on carrying capacity of beaches and the adjacent private areas was undertaken by National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Carrying capacity was determined using several international and national best practices to determine the scenarios and indicators for the assessment. -

The Problem of Maratha Totemism 137

The Indian Journal of Social Work, Vol. XXV, No. 2 (July 1964). THE PROBLEM OF JOHN V FERREIRA MARATHA TOTEMISM In the Marathi-speaking areas of Western India, there are several castes and tribes which exhibit the phenomenon of the devak. Many interpreters of the phenomenon, which is found at its strongest among the Marathas and the occupational castes related to or influenced by them, and less strongly among the primitive tribes of the. region, have characterized it as a form of totemism. A few interpreters, however, have called the totemic" character of the devak into question. The object of this article is, therefore, to re-examine the factual evidence and the more prominent of its interpretations in order to arrive 'at the Origin, the true nature " and the significance of the phenomenon. - - "Mr. Ferreira is Reader in Sociology, University of Bombay. An early observer, James Campbell, noted The most detailed accounts of the that the Marathas of the Bombay Presidency Maratha devaks, however, have been given were divided into families, each with its to us by R. E. Enthoven. Referring to the devak or sacred symbol The devaks were Marathas. proper, to the Maratha Kunbis, patrilineally inherited, and worshipped at and to the Maratha occupational castes (the marriages and other important occassions. Bhandari, the Chitrakathi, the Gavandi,, the Persons with the same devak were not Kumbhar, the Lohar, the Mali, the Nhavi, permitted to marry. Of the devak listed, the Parit, the Sutar, the Taru., the Teli and 18 are trees and their products and 9 are so on), he says that their exogamous groups inanimate objects. -

Folk Theatre in Goa: a Critical Study of Select Forms Thesis

FOLK THEATRE IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECT FORMS THESIS Submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY For the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar Under the Guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K. J. Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. January 2018 CERTIFICATE As required under the University Ordinance, OA-19.8 (viii), I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, submitted by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English has been completed under my guidance. The thesis is the record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to her by this or any other University. Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. Date: i DECLARATION As required under the University Ordinance OA-19.8 (v), I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley, Professor of English (Retd.),Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in the thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to me, by this or any other University. Ms. -

Impact of Christian Missions an Overview

www.sosinclasses.com CHAPTER 4 IMPACT OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONS AN OVERVIEW 4.1 The Impact of missions, a summing up 4.2 Christian missions and English education CHAPTER FOUR IMPACT OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONS-AN OVERVIEW 4.1 The impact of missions, a summing up In the preceding part an attempt was made to understand the Christian missions in India in terms of western missionary expansion. As stated earlier, India had a hoary tradition of tolerance and assimilation. This tradition was the creation of the syncretic Hindu mind eager to be in touch with all other thought currents. “Let noble thoughts come to us from all sides”1 was the prayer of the Hindu sages. The early converts to Christianity lived cordially in the midst of Hindus respecting one another. This facilitated the growth of Christianity in the Indian soil perfectly as an Indian religion. The course of cordiality did not run smooth. The first shock to the cordial relation between Christian community and non-Christians was received from the famous Synod of Diamper. Latin rites and ordinances were imposed forcefully and a new world of Christendom was threatened to be extended without caring to understand the social peculiarities of the place where it was expected to grow and prosper and ignoring the religio-cultural sensitivity of the people amidst whom the 1 Rigveda 1-89-1. www.sosinclasses.com 92 new religion was to exist. As pointed out earlier the central thrust of the activities of the Jesuit missions established in India during the second half of sixteenth century was proselytizing the native population to Christianity. -

Fellowship Prospectus.Cdr

Late Fabian B.L. Colaco & Smt. Alice Colaco Vishwa Konkani Bhasha Samsthan World Institute of Konkani Language (Research and Studies) World Konkani Centre, Konkani Gaon, Shakti Nagar, Mangalore - 575016 Phone: 2232896, 2231877, Fax: 2231887 Email: [email protected] www.vishwkonkani.org FELLOWSHIP PROGRAMME Late Fabian B.L. Colaco and Smt. Alice Colaco Konkani Language and Cultural Foundation is thankful to Shri Ronald Colaco and Family for their contribution towards the infrastructure and facilities at World Institute of Konkani Language. Shri Colaco is one among the Trustees of the Foundation and a generous philanthropist. Shri Ronald Colaco LATE FABIAN B.L. COLACO & SMT. ALICE COLACO VISHWA KONKANI BHASHA SAMSTHAN WORLD INSTITUTE OF KONKANI LANGUAGE (RESEARCH AND STUDIES) FELLOWSHIP PROGRAMME KONKANI LANGUAGE AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION (R) WORLD KONKANI CENTRE, KONKANI GAON, SHAKTI NAGAR, MANGALORE - 575016 PHONE: 2232896, 2231877, FAX: 2231887 EMAIL: [email protected] WWW.VISHWAKONKANI.ORG Late Fabian B.L. Colaco & Smt. Alice Colaco Vishwa Konkani Bhasha Samsthan World Institute of Konkani Language (Research and Studies) President Shri Basti Vaman Shenoy Director Dr. Tanaji Halarnakar, Goa Members of Advisory Board Dr. Rocky V. Miranda, Mysore Dr. Suneetha Bai, Kochi Dr. Prakash Vazrikar, Goa Asst. Director Shri Gurudath Bantwalkar Cover page depicts the 12th Century inscription in Konkani Language at the feet of Bhagavan Bahubali of Shravana Belagola, Karnatak. FOREWORD After completion of construction of World Konkani Centre, now the Konkani Language and Cultural Foundation has embarked on various projects envisaged in my VISION Document. And at the outset Research and Studies under Vishwa Konkani Bhasha Samsthan (World Institute of Konkani Language (research and studies)) has commenced. -

Khabbar Vol. XXXIX No. 3 (July, August, September

Khabbar North American Konkani Newsletter Volume XXXIX No. 3 July, August, September - 2016 From: The Honorary Editor, "Khabbar" P. O. Box 222 Lake Jackson, TX77566 - 0222 XXXIX-3 ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED FIRST CLASS TO: Khabbar XXXIX No. 3 Page: 1 Khabbar Follies In this section, Khabbar looks into the Konkani community and anything and everything that is Konkani from a Konkani point of view. The names will never be published but geographic location will be identified in general terms. There is no doubt in my mind that Khabbar is a part & parcel of life of Konkanis in North America. In fact, Khabbar has developed a special relation with most of the Konkani families and here are some examples of those close encounters of a different kind….…… The Konkani Sammelan 2016 in Atlanta was a fabulous event. everybody’s relief, at the end of the sammelan, there was a Kudos to the Team KAOG who did an outstanding job for a surplus! successful sammelan. But, the financial situation was bleak! Before the sammelan started, there was a forecast of heavy Thanks to everyone who came to the rescue to make KS-2016 deficit!! For various reasons, the anticipated fund raising did a complete success. not materialize. Team NAKA and Team KAOG did an extreme fund raising and the Konkani community at large Editor’s Reply: opened their heart and the wallet. All said and done, to Now, that is what I say is the Konkani spirit. ***** SUBSCRIPTION FORM: Dear Konkani family, It is time to renew your subscription for 2016.The numbers on the mailing label clearly indicate the year/s the dues for Khabbar has been received since 2014. -

Official Gazette

, ' ) 'REGD. GOA ~ 5 , . Panaji, 18th April, 1985 (Chaifra 28, 19C7J SERIES ,m No.3 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF ,GOA~. DAMAN AND DIU- !,w .• 'GOVERNMENT OF GOA. DAMAN '0. I. D,Bran~)i; Pannjl i!ifOn)led that Shri I),Souza left Goa ""d lrtlo/~t9r Jew df'ys at Bombil,y tJiom., wItere,'?,!}!;, went to J!;qV.;ii.!t wllere lIe Is serving. Howevei, his0d4rel!S at AND DIU Kuw>dt Is .tlot !=)IYJl. " Department of Personnel and Administrative Reforms" !,I!avft ~~IIY ~.ed tM Pl"Ol! and cons Qf' the case ,0lIII )lave come to tile conclUSion 'tlmt Shri D'Souza, !:.ower General Adminlslralion and Co-ordination Division Dlvislon Clerk, W6rk1ng I!'the Office of the DePl!ty Colleetor, Office of the Collector of G:oa South, MargaI' under this Collectorate of Goa, by hl~ un authorised a~ee ft""rn duties and nof keepln~ the Office infO~ of his 'whereabouts has committed gross mis.:conduct Order and has, therefQre faUed to lnstntaln absolute' devotion to , duties. I, am there.fore, satisfied that Shri D'Souza, L. D. C .. ' No.'12(6)/128j83-EST/COr. iB pot a fit pe~ t~()r retention in Govei'IlJnent Service as' Shri Joseph D'Souza,' Lower Division Clerk 'Working in r.. D. C. I" am also Satisfied that it is nQtreasonablyprscU" the Office of the Deputy Collector, South, ~'\9 \!Ader , callie to !lold an Inqun-y in a, manner provided under Rule 14 this ColIectorate Is absent from duties from 8-12-1983. and 15 of the Central Civil Services (Classification, Control ,and Appeal) Rules, 1965 against Shri D'Souza.' Therefore, Shri Joseph D'Souza had applied for earned leave on I feel 'that ,the only course left to dispose of the case is 31-10-1983 for a period of 30 days with effect from 8-11·1983 by invocation of the provisions of ,Rule 19(ii) Ibid, ' to 7-12-1983 wbk:h was granted to him vl(j@ or4<!t' N(>. -

Catalogue of Marathi and Gujarati Printed Books in the Library of The

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofmaratOObrituoft : MhA/^.seor,. b^pK<*l OM«.^t«.lT?r>">-«-^ Boc.ic'i vAf. CATALOGUE OF MARATHI AND GUJARATI PRINTED BOOKS IN THE LIBRARY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. BY J. F. BLUMHARDT, TEACHBB OF BENBALI AT THE UNIVERSITY OP OXFORD, AND OF HINDUSTANI, HINDI AND BBNGACI rOR TH« IMPERIAL INSTITUTE, LONDON. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. •» SonKon B. QUARITCH, 15, Piccadilly, "W.; A. ASHER & CO.; KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TKUBNER & CO.; LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. 1892. /3 5^i- LONDON ! FEINTED BY GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, VD., ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLKBKENWEIL BOAD, E.C. This Catalogue has been compiled by Mr. J. F. Blumhardt, formerly of tbe Bengal Uncovenanted Civil Service, in continuation of the series of Catalogues of books in North Indian vernacular languages in the British Museum Library, upon which Mr. Blumhardt has now been engaged for several years. It is believed to be the first Library Catalogue ever made of Marathi and Gujarati books. The principles on which it has been drawn up are fully explained in the Preface. R. GARNETT, keeper of pbinted books. Beitish Museum, Feb. 24, 1892. PEEFACE. The present Catalogue has been prepared on the same plan as that adopted in the compiler's " Catalogue of Bengali Printed Books." The same principles of orthography have been adhered to, i.e. pure Sanskrit words (' tatsamas ') are spelt according to the system of transliteration generally adopted in the preparation of Oriental Catalogues for the Library of the British Museum, whilst forms of Sanskrit words, modified on Prakrit principles (' tadbhavas'), are expressed as they are written and pronounced, but still subject to a definite and uniform method of transliteration.