The Problem of Maratha Totemism 137

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk Theatre in Goa: a Critical Study of Select Forms Thesis

FOLK THEATRE IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECT FORMS THESIS Submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY For the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar Under the Guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K. J. Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. January 2018 CERTIFICATE As required under the University Ordinance, OA-19.8 (viii), I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, submitted by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English has been completed under my guidance. The thesis is the record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to her by this or any other University. Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. Date: i DECLARATION As required under the University Ordinance OA-19.8 (v), I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley, Professor of English (Retd.),Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in the thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to me, by this or any other University. Ms. -

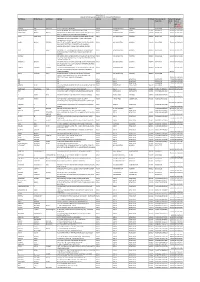

The Maharashtra State Coop Bank Ltd Mumbai Voters List Ledger Member Registration Consti- Default Sr

THE MAHARASHTRA STATE COOP BANK LTD MUMBAI VOTERS LIST LEDGER MEMBER REGISTRATION CONSTI- DEFAULT SR. NO. NAME ADDRESS REMARK NO. NO. NUMBER / DATE TUENCY ER (Y/N) NAME OF THE CONSTITUNCEY-50F------OTHERS SHETKARI SAH. KHARDI VIKRI & PROCESSING STY 1 I/6/26 906 TAL. - PATUR, DIST. AKOLA, PIN 444501 DR-1283 DT. 7/2/1961 50 (F) N F LTD, PATUR. HIWARKHED KRISHI PRAKRIYA SAH. SANSTHA AT/POST - HIWARKHED (RUPRAO), TAL. AKL/PRG/A/113 DT. 2 F/4/11 655 50 (F) N F HIWARKHED AKOT, DIST. AKOLA, PIN 444001 15/02/1973 THE COOPERATIVE GINNING & PRESSING FACTORY MANA(C.R.), TAL. - MURTIZAPUR, DIST. - AKL/PRG/(A)/114 DT. 3 F/3/42 658 50 (F) N F LTD. MANA AKOLA, PIN - 444107 24/09/1974 MURTIZAPUR CO-OP. GINNING & PRESSING FACTORY AT POST - MURTIZAPUR, TAL. - AKL/PRG/(A)106 DT. 4 F/3/67 872 50 (F) N F LTD. MURTIZAPUR, DIST. AKOLA, PIN 444107 15/03/1965 A.P.M.C. YARD, POPAT KHED ROAD, NARNALA PARISAR BIJ UTPADAK VA PRAKRIYA AKL/PRG/A/957 DT. 5 F/4/23 907 AKOLA, TAL. - AKOLA, DIST. - AKOLA, PIN 50 (F) N SANSTHA LTD. AKOLA 1/9/1982 F - 444001 TELHARA TALUKA SAHAKARI GINNING & PRESSING AT POST - TELHARA, TAL. - AKOT, DIST. AKL/PRG/(A)/104 DT. 6 F/3/88 2304 50 (F) N F STY. LTD. TELHARA AKOLA, PIN 444108 8/2/1964 AKOLA GINNING & PRESSING CO-OP FACTORY LTD. NEAR MAHATMA MILLS, AT POST - DR/1277 OF 1960 DT. 7 F/3/46 2308 50 (F) N F AKOLA, AKOLA, TAL.-AKOLA, PIN 444001 1/2/1960 GRAM VIKAS SAH. -

Political Economy of a Dominant Caste

Draft Political Economy of a Dominant Caste Rajeshwari Deshpande and Suhas Palshikar* This paper is an attempt to investigate the multiple crises facing the Maratha community of Maharashtra. A dominant, intermediate peasantry caste that assumed control of the state’s political apparatus in the fifties, the Marathas ordinarily resided politically within the Congress fold and thus facilitated the continued domination of the Congress party within the state. However, Maratha politics has been in flux over the past two decades or so. At the formal level, this dominant community has somehow managed to retain power in the electoral arena (Palshikar- Birmal, 2003)—though it may be about to lose it. And yet, at the more intricate levels of political competition, the long surviving, complex patterns of Maratha dominance stand challenged in several ways. One, the challenge is of loss of Maratha hegemony and consequent loss of leadership of the non-Maratha backward communities, the OBCs. The other challenge pertains to the inability of different factions of Marathas to negotiate peace and ensure their combined domination through power sharing. And the third was the internal crisis of disconnect between political elite and the Maratha community which further contribute to the loss of hegemony. Various consequences emerged from these crises. One was simply the dispersal of the Maratha elite across different parties. The other was the increased competitiveness of politics in the state and the decline of not only the Congress system, but of the Congress party in Maharashtra. The third was a growing chasm within the community between the neo-rich and the newly impoverished. -

Social Organization Among Halakkis: a Study in Uttara Kannada District

[ VOLUME 3 I ISSUE 1 I JAN. – MARCH 2016] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 SOCIAL ORGANIZATION AMONG HALAKKIS: A STUDY IN UTTARA KANNADA DISTRICT RaghavaNaik Co-ordinator, P.G. Department of Sociology Govt First Grade College and Centre for P.G. Studies, Thenkanidiyur, Udupi Received Feb 20, 2015 Accepted March 10, 2016 ABSTRACT Social organization of Halakkis is different from other tribal folk in Karnataka. But, like other communities among Halakkis family is a basic institution of society. It plays an important role in the upbringing and socialization of the younger generation. Family also internalizes among the children the basic values of society which are needed to function as a member of society. Halakki community is an endogamous group. All the members of the community develop a sense of belonging. There are a number of clans among the Halakki. These clans are exogamous units and there are eighteen such clans. Kaur (1977:33) points out, “Kinship is the combination of culturally utilized rules, including marriage, residence rules, rules of succession and inheritance and rules of descent, which place individuals and groups in definite relationship to each other within a society.” Introduction: The Coastal Karnataka comprising of three major Districts, Uttara Kannada, Dakshina Kannada and Udupi. The present article is the study of the Social Organization of Halakki community of Uttara Kannada District. This paper is based on the data collected for the Doctoral thesis entitled “The Role of Halakki Women of Uttara Kannada District in Economic Productivity and Ecological Sustainability”. Primary data was collected by using the interview method taking 300 samples from Halakkis in Uttara Kannada District. -

Memory, Postmemory and the Role of Narratives Among Women Writers from the Adivasi Communities of Goa

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2021.e78365 MEMORY, POSTMEMORY AND THE ROLE OF NARRATIVES AMONG WOMEN WRITERS FROM THE ADIVASI COMMUNITIES OF GOA Cielo G. Festino1* 1Universidade Paulista, São Paulo, SP, Brasil Andréa Machado de Almeida Mattos2** 2Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil Abstract: The aim of this paper is to analyze the life narratives “Where have All the Songs and Rituals Gone?” (2019) by Mozinha Fernandes and “A Velip Writes Back” (2019) by Priyanka Velip, members of the Adivasi community of Goa, who consider themselves as the first inhabitants of this Indian state. These narratives have been published in the blog “Hanv Konn. Who am I? Researching the Self” organized by the late professor from the University of Goa, Alito Siqueira, whose aim is to give voice to this marginalized and silenced community. The analysis will be done in terms of the concepts of Postmemory (Hirsch, 1996, 1997, 2008), Trauma (Ginzburg, 2008; Balaev, 2008), Narrative (Bruner, 2002; Coracini, 2007), and Life-narratives (Smith & Watson, 2010). Keywords: Adivasis; postmemory; trauma; narratives; life narratives. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Professor Alito Siqueira (1955-2019) * Teaches English at Universidade Paulista, São Paulo, Brazil. She is a member of the project ‘Thinking Goa: A Singular Archive in Portuguese (2015–2019)’, funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation. She is co-editor, with Paul Melo e Castro, of A House of Many Mansions: Goan Literature in Portuguese. An Anthology of Original Essays, Short Stories and Poems (Under the Peepal Tree, 2017), and, with Paul Melo e Castro, Hélder Garmes, and Robert Newman, of ‘Goans on the Move’, a special issue of Interdisciplinary Journal of Portuguese Diaspora Studies 7 (2018). -

Aurobindo Pharma Limited Detailed List Of

AUROBINDO PHARMA LIMITED DETAILED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS' UNPAID/UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND AMOUNT FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2013-14 (INTERIM) Proposed Date of Amount Due transfer to IEPF (DD- First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband FirstName Father/Husband Middle Name Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District Pincode Folio No of Securities Investment Type in Rs. MON-YYYY) VASANT D LAD NA B 1601 16TH FLOOR WILLOWS TOWER VASANT GARDEN NEAR SWAPNA NAGARI MULUND WEST MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400080 IN30112715194202 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 5000.00 11-DEC-2020 CHANDRAKANT GANDHI SURYAKANT GANDHI A/401 GAYATRI KRUPA BLDG 4TH FLOOR OPP PUNJAB & SIND BANK L T ROAD VAZIRA NAKA BORIVALI W MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400092 IN30075710789682 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 1563.00 11-DEC-2020 MEENA BHAUSAHEB SHINDE BHAUSAHEB BABAN SHINDE KRISHNA NAGAR BEHIND APARNA SOCIETY CHENDANI KALIWADA THANE EAST INDIA MAHARASHTRA THANE 400602 0APL003134 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 2500.00 11-DEC-2020 SUBHDRA K KSHIRSAGAR K G KSHIRSAGAR A-5 GOKHALE INSTITUTE STAFF QUARTERS 832 B SHIVAJI NAGAR PUNE INDIA MAHARASHTRA PUNE 411004 0APL003384 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 5000.00 11-DEC-2020 MEENAKSHI K K K G KSHIRSAGAR A5 GOKHALE INSTITUTE STAFF QUARTERS 832 B SHIVAJI NAGAR PUNE INDIA MAHARASHTRA PUNE 411004 0APL003385 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 5000.00 11-DEC-2020 MANGAL BHANGDIYA OM NARAYAN BHANGDIYA SARAF LANE LATUR INDIA MAHARASHTRA LATUR 413512 0APL003207 Amount for unclaimed -

Lesson from Krishna Kidnapping Rukmini Part-01

Satyanand Pr | Lesson from Krishna Kidnapping Rukmini 27 September 2020 11:51 27.09.2020 Topic - Lesson from Krishna Kidnapping Rukmini - Part 1 By Satyanand Pr • King bhishmaka don’t wanted to give rukmini to krsna and wanted to give rukmi who was an envious and wanted to give to shishupal • Similarly, Soul is like rukmini who wants to unite the Lord but material world is like rukma who wants to give to material illusory energy known as shishupal and bhishmika is like intelligent and although we are intelligent we have weakness that we follows the material nature and soul has to free himself from materialistic mind and weakness • awareness, desire and seek spiritual master who can unite with Lord And we also do that sincerely • When rukmini hears the glories of lord, she attracts. Similarly, when we listen to hear the glories of lord then the desire to get attract to Lord gets sprouted and because of conditioned mind we cannot able to get attract to Lord. • There must be saintliness in character who is free from pride and free from ego and who has well wishing to every living entities. He is real spiritual master • Sincere sadhakas doesn’t get fall away from the lord and hearing from the lord we can able to destroy gross and subtle body and also Seeing Krsna's form then we can get free from all our material desires • Rukmini glorifying Lord's qualities that You are greater that you have great lineage, good character, beautiful, knowledgeable, your age is perfect and opulence's, delightful and Krsna - You are the most power personality but delightful as well and present moment is the best way to • Association of krsna brings smiles or happiness which is like a jasmine bird and you have an opportunity to bring smile in me • Rukmini says that I am chosen you as your husband and servant of yours so please come and please take me to your shelter and I also want you to • Many times, we think that if lord comes in me then I will take shelter. -

Dayanand Balkrishna Bandodkar : the Architect of Modern Goa

DAYANAND BALKRISHNA BANDODKAR : THE ARCHITECT OF MODERN GOA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in Goa University N. RADHAKRISHNAN, M.A., DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA. 1994 • Map of Goa • ok- •••••••-- .••••■ •-■ —aaw H T A albaga •condr (HN(M Alma for brawl Net 4-1 Susquirsraie acasana Colvale ssonora ueri \\ unchehm ®\M g / ulraR agueri Hills Tanem \ °opera kin Gomel %Vaporer Beech Harm Lek lt‘tryirrie Beach Ouelgate &Pr , Verangute Beach AL POI 'etIm Caranzot 4ndebni Botch tha Goa Agsgria for anastarim I. nr Of alle rondum • Gavandoas Beach Santana Nock Manguesh and OLA SANCTUARY CAB • 'Filar Monastry ardol Temple mb o la D. Paula U ao Shang ilium NORAVG Opt Wa orks RHAGWA EM VASCO MA Darbandora SAN hret-Rim lalSancoale olem On aranzol R.S. soak ch Bea (idly Rsaulim mbora Cairn minary Coln Bea ARGAO alay R.S. Arabiah Sea Mar Chancor R.S urchorem Benaiiiim Bea Sanvordem R S Maulingue N V 8 • C ha ndera Temple• lamola OUEP Cevelosst ambaultm Te Cumbari Amba i II ena Mahar Bead alto tvona urdi , Gallem atorpa Bard Beasch Shan( urga Tem rla Netorlim Cabo De Rama abo de Rama. Tort Deucorpem Mallikarsun Temple • COMA° REFERENCES Palolam SANCTUARY STATE 110LAIOARY • • LOCATION Talpo Cotigao ROADS TEMPLE CHURCH ■ SORT • G•VMAINhet el Mina Copytiile Ce AIRPORT &owl up*0 UNA, Ai WHIM* OM 00ANNO18084/ it/ j SAVSWYWAS 4~1/ Ai 848. ' , AIR ROUTE RAILWAY III TA* twiteekl trotiwa AI Wks .le He'l:N; IA a aapaai• e(artIsa, maaiaggaga* •oarjaykta_ase tar2)gatxtvasaa aaa. -

Krishna Kidnaps Rukmini

Krishna Kidnaps Rukmini Krishna Kidnaps Rukmini Amravati [47:17] 10.52-53 Srimad Bhagavatam, chapter fifty two and fifty three, is description of the kidnapping of the Rukmini. This is Bhagavatam is here in front of me. Devotees have to go on a nagar procession, nagar sankirtana and before that we have to take breakfast, but before that we have class. Rajo uvaca, so King Pariksit, was very fond of hearing that beautiful past, King Pariksit was very inquisitive to know, Sukdev Goswami has mentioned earlier that he had mentioned about , vaidarbhim bhismaka-sutam [SB 10.52.16] Vaidharbhi Rukmini the daughter of King Bhismaka and it is about her marriage, as we know that King Pariksit is very curious to know. So, rukminim rucirananam [SB 10.52.18] Rukmini, very sweet, sweet faced rucirananam. bhagavan srotum icchami krsnasyamita-tejasah [SB. 10.52.19] Parikshit said, My lord, I wish to hear how the immeasurably powerful Lord Krsna took away His bride. Suko Uvacha and then he begins, the Sukadeva Goswami began. So there was once upon a time, there was a king Bhismaka, who was ruling in state or kingdom called Vidarbha. rajasid bhismako nama vidarbhadhipatir mahan tasya pancabhavan putrah kanyaika ca varanana [SB.10.52.21] He had five sons and one very beautiful daughter, and five names of the five brothers of Rukmini are mentioned and then main introduction to Rukmini. sopasrutya mukundasya rupa-virya-guna-sriyah [SB10.52.23] This Rukmini, she used to hear about Rupa- the form, the beauty, Virya- the strength, Guna- qualities of Mukunda. -

First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State

Biocon Limited Amount of unclimed and unpaid Interim dividend for FY 2010-11 First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Amount Proposed Securities Due(in Date of Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) JAGDISH DAS SHAH HUF CK 19/17 CHOWK VARANASI INDIA UTTAR PRADESH VARANASI BIO040743 150.00 03-JUN-2018 RADHESHYAM JUJU 8 A RATAN MAHAL APTS GHOD DOD ROAD SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395001 BIO054721 150.00 03-JUN-2018 DAMAYANTI BHARAT BHATIA BNP PARIBASIAS OPERATIONS AKRUTI SOFTECH PARK ROAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO001163 150.00 03-JUN-2018 NO 21 C CROSS ROAD MIDC ANDHERI E MUMBAI JYOTI SINGHANIA CO G.SUBRAHMANYAM, HEAD CAP MAR SER IDBI BANK LTD, INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO011395 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ELEMACH BLDG PLOT 82.83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI EAST, MUMBAI GOKUL MANOJ SEKSARIA IDBI LTD HEAD CAPITAL MARKET SERVIC CPU PLOT NO82/83 INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO017966 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 15 OPP SPECIALITY RANBAXY LABORATORI ES MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI-4000093 DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 150.00 03-JUN-2018 PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MKT SER INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 150.00 03-JUN-2018 C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 150.00 03-JUN-2018 -

Kunkeri Village Survey Monograph, Part VI (I), Vol-X

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME X MAHARASHTRA PART VI (1) KUNKERI VILLAGE SURVEY MONOGRAPH Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS OFFICE, BOMBAY 1966 PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE MANAGER, GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS, BOMBAY AND PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI-8 .L IQI;fM.LNVM\;IS .q: I ~ -.I J "t .... c ,,) ::> :x: I:) CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 Central Government Publications Census Report, Volume X-Maharashtra, is published in the following Parts I-A and B General Report I-C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables. II-B (i) General Economic Tables-Industrial Classification II-B (ii) General Economic Tables-Occupati.onal Classificati.on. II-C (i) ~ocial and Cultural Tables II-C (ii) Migration Tables III Househ.old Economic Tables IV Report on Housing and Establishments V-A - Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in Maharashtra-Tables V-B Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in Maharashtra-Ethnographic N.otes. VI (1-35) Village Surveys (35 monographs on 35 selected villages) VII-A (1-8) .. Handicrafts in Maharashtra (8 monographs on 8 selected Handicrafts) VII-B Fairs and Festivals in Maharashtra / VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration (For official use only) VIII-B Administration Rep.ort-Tabulati.on (For official use only) IX Census Atlas of Maharashtra X (1-12) Cities .of Maharashtra (15 volumes-Four volumes on Greater Bombay and One each on other eleven Cities) State Government Publications 25 Volumes .of District Census Handbooks in English . , 25 V.olumes .of District Census Handbooks in Marathi Alphabetical List .of Villages and T.owns in Maharashtra FOREWORD Apart from laying the foundations of demography in this subcontinent, a hundred years of the Indian Census has also produced' elaborate and scholarly accounts of the variegated phenomena of Indian life-sometimes with no statistics attached, but usually with just enough statistics to give empirical underpinning to their conclusions'. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. Furtherowner. reproduction Further reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. HISTORICISM, HINDUISM AND MODERNITY IN COLONIAL INDIA By Apama Devare Submitted to the Faculty of the School of International Service of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In International Relations Chai Dean of the School of International Service 2005 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3207285 Copyright 2005 by Devare, Aparna All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3207285 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.