Kunkeri Village Survey Monograph, Part VI (I), Vol-X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siva Chhatrapati, Being a Translation of Sabhasad Bakhar with Extracts from Chitnis and Sivadigvijaya, with Notes

SIVA CHHATRAPATI Extracts and Documents relating to Maratha History Vol. I SIVA CHHATRAPATI BEING A TRANSLATION OP SABHASAD BAKHAR WITH EXTRACTS FROM CHITNIS AND SIVADIGVTJAYA, WITH NOTES. BY SURENDRANATH SEN, M.A., Premchaxd Roychand Student, Lectcrer in MarItha History, Calcutta University, Ordinary Fellow, Indian Women's University, Poona. Formerly Professor of History and English Literature, Robertson College, Jubbulpore. Published by thz UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA 1920 PRINTED BY ATCLCHANDKA BHATTACHABYYA, AT THE CALCUTTA UNIVEB8ITY PEE 88, SENATE HOUSE, CALCUTTA " WW**, #rf?fW rT, SIWiMfT, ^R^fa srre ^rtfsre wwf* Ti^vtm PREFACE The present volume is the first of a series intended for those students of Maratha history who do not know Marathi. Original materials, both published and unpublished, have been accumulating for the last sixtv years and their volume often frightens the average student. Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, therefore, suggested that a selection in a handy form should be made where all the useful documents should be in- cluded. I must confess that no historical document has found a place in the present volume, but I felt that the chronicles or bakhars could not be excluded from the present series and I began with Sabhasad bakhar leaving the documents for a subsequent volume. This is by no means the first English rendering of Sabhasad. Jagannath Lakshman Mankar translated Sabhasad more than thirty years ago from a single manuscript. The late Dr. Vincent A. Smith over- estimated the value of Mankar's work mainly because he did not know its exact nature. A glance at the catalogue of Marathi manuscripts in the British Museum might have convinced him that the original Marathi Chronicle from which Mankar translated has not been lost. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: Vasant Joshi © B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Preface by : Dr. Vijay Bhatkar, Chief Mentor, Multiversity. * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 26th January 2021 YOGA INFLUENCE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF G My Brother My Sister Late Prabhakar Joshi Late Sudha Natu yG y YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. Part I Preface - Dr. Vijay Bhatkar I Prologue of English Translator - Vasant Joshi IV Acquaintance - Dr. K. M. Ghatate VI Autobiography of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj XLII Introduction - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LI Swami Bechiranand - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LVI Tribute - Vasant Joshi LIX Part II Chapter I : Introduction 4 to 37 Aphorism 1 to 22 Chapter II : God Meditation 38 to 163 Aphorism 23 to 33 Chpter III : Study 164 to 300 Aphorism 34 to 39 Chapter IV : Fruit of Yoga Study 301 to 357 Aphorism 40 to 44 Pious Behaviour Indication 358 to 362 Steps Perfection 363 to 370 Part III Appendix : Glossary of Technical Terms 373 to 395 References 396 G YOGA INFLUENCE PART I YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. -

INDIA Transcript of Flavia Agnes Intervie

GLOBAL FEMINISMS: COMPARATIVE CASE STUDIES OF WOMEN’S ACTIVISM AND SCHOLARSHIP SITE: INDIA Transcript of Flavia Agnes Interviewer: Madhushree Datta Location: Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Date: 16-17 August, 2003 Language of Interview: English SPARROW Sound & Picture Archives for Research on Women B-32, Jeet Nagar, J.P. Road, Versova, Mumbai-400061 Tel: 2824 5958, 2826 8575 & 2632 8143 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.sparrowonline.org Acknowledgments Global Feminisms: Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship was housed at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan (UM) in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The project was co-directed by Abigail Stewart, Jayati Lal and Kristin McGuire. The China site was housed at the China Women’s University in Beijing, China and directed by Wang Jinling and Zhang Jian, in collaboration with UM faculty member Wang Zheng. The India site was housed at the Sound and Picture Archives for Research on Women (SPARROW) in Mumbai, India and directed by C.S. Lakshmi, in collaboration with UM faculty members Jayati Lal and Abigail Stewart. The Poland site was housed at Fundacja Kobiet eFKa (Women’s Foundation eFKa) in Krakow, Poland and directed by Slawka Walczewska, in collaboration with UM faculty member Magdalena Zaborowska. The U.S. site was housed at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan and directed by UM faculty member Elizabeth Cole. Graduate student interns on the project included Nicola Curtin, Kim Dorazio, Jana Haritatos, Helen Ho, Julianna Lee, Sumiao Li, Zakiya Luna, Leslie Marsh, Sridevi Nair, Justyna Pas, Rosa Peralta, Desdamona Rios and Ying Zhang. -

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

Satara. in 1960, the North Satara Reverted to Its Original Name Satara, and South Satara Was Designated As Sangli District

MAHARASHTRA STATE GAZETTEERS Government of Maharashtra SATARA DISTRICT (REVISED EDITION) BOMBAY DIRECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONARY AND PUBLICATION, MAHARASHTRA STATE 1963 Contents PROLOGUE I am very glad to bring out the e-Book Edition (CD version) of the Satara District Gazetteer published by the Gazetteers Department. This CD version is a part of a scheme of preparing compact discs of earlier published District Gazetteers. Satara District Gazetteer was published in 1963. It contains authentic and useful information on several aspects of the district and is considered to be of great value to administrators, scholars and general readers. The copies of this edition are now out of stock. Considering its utility, therefore, need was felt to preserve this treasure of knowledge. In this age of modernization, information and technology have become key words. To keep pace with the changing need of hour, I have decided to bring out CD version of this edition with little statistical supplementary and some photographs. It is also made available on the website of the state government www.maharashtra.gov.in. I am sure, scholars and studious persons across the world will find this CD immensely beneficial. I am thankful to the Honourable Minister, Shri. Ashokrao Chavan (Industries and Mines, Cultural Affairs and Protocol), and the Minister of State, Shri. Rana Jagjitsinh Patil (Agriculture, Industries and Cultural Affairs), Shri. Bhushan Gagrani (Secretary, Cultural Affairs), Government of Maharashtra for being constant source of inspiration. Place: Mumbai DR. ARUNCHANDRA S. PATHAK Date :25th December, 2006 Executive Editor and Secretary Contents PREFACE THE GAZETTEER of the Bombay Presidency was originally compiled between 1874 and 1884, though the actual publication of the volumes was spread over a period of 27 years. -

The Problem of Maratha Totemism 137

The Indian Journal of Social Work, Vol. XXV, No. 2 (July 1964). THE PROBLEM OF JOHN V FERREIRA MARATHA TOTEMISM In the Marathi-speaking areas of Western India, there are several castes and tribes which exhibit the phenomenon of the devak. Many interpreters of the phenomenon, which is found at its strongest among the Marathas and the occupational castes related to or influenced by them, and less strongly among the primitive tribes of the. region, have characterized it as a form of totemism. A few interpreters, however, have called the totemic" character of the devak into question. The object of this article is, therefore, to re-examine the factual evidence and the more prominent of its interpretations in order to arrive 'at the Origin, the true nature " and the significance of the phenomenon. - - "Mr. Ferreira is Reader in Sociology, University of Bombay. An early observer, James Campbell, noted The most detailed accounts of the that the Marathas of the Bombay Presidency Maratha devaks, however, have been given were divided into families, each with its to us by R. E. Enthoven. Referring to the devak or sacred symbol The devaks were Marathas. proper, to the Maratha Kunbis, patrilineally inherited, and worshipped at and to the Maratha occupational castes (the marriages and other important occassions. Bhandari, the Chitrakathi, the Gavandi,, the Persons with the same devak were not Kumbhar, the Lohar, the Mali, the Nhavi, permitted to marry. Of the devak listed, the Parit, the Sutar, the Taru., the Teli and 18 are trees and their products and 9 are so on), he says that their exogamous groups inanimate objects. -

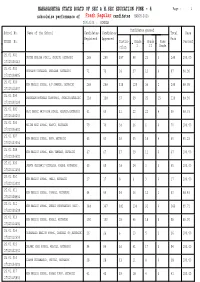

School Wise Result Statistics Report

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 25.01.001 UNITED ENGLISH SCHOOL, CHIPLUN, RATNAGIRI 289 289 197 66 23 3 289 100.00 27320100143 25.01.002 SHIRGAON VIDYALAYA, SHIRGAON, RATNAGIRI 71 71 24 27 12 4 67 94.36 27320108405 25.01.003 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, A/P SAWARDE, RATNAGIRI 288 288 118 129 36 2 285 98.95 27320111507 25.01.004 PARANJAPE MOTIWALE HIGHSCHOOL, CHIPLUN,RATNAGIRI 118 118 37 39 25 15 116 98.30 27320100124 25.01.005 HAJI DAWOOD AMIN HIGH SCHOOL, KALUSTA,RATNAGIRI 61 60 11 22 22 4 59 98.33 27320100203 25.01.006 MILIND HIGH SCHOOL, RAMPUR, RATNAGIRI 70 70 38 26 6 0 70 100.00 27320106802 25.01.007 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, BHOM, RATNAGIRI 65 63 16 30 10 4 60 95.23 27320103004 25.01.008 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, MARG TAMHANE, RATNAGIRI 67 67 17 39 11 0 67 100.00 27320104602 25.01.009 JANATA MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KOKARE, RATNAGIRI 65 65 38 24 3 0 65 100.00 27320112406 25.01.010 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, OMALI, RATNAGIRI 17 17 8 6 3 0 17 100.00 27320113002 25.01.011 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, POPHALI, RATNAGIRI 64 64 14 36 12 1 63 98.43 27320108904 25.01.012 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KHERDI-CHINCHAGHARI (SATI), 348 347 181 134 31 0 346 99.71 27320101508 25.01.013 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, NIWALI, RATNAGIRI 100 100 29 46 18 6 99 99.00 27320114405 25.01.014 RATNASAGAR ENGLISH SCHOOL, DAHIWALI (B),RATNAGIRI 26 26 6 13 5 2 26 100.00 27320112604 25.01.015 DALAWAI HIGH SCHOOL, MIRJOLI, RATNAGIRI 94 94 36 41 17 0 94 100.00 27320102302 25.01.016 ADARSH VIDYAMANDIR, CHIVELI, RATNAGIRI 28 28 13 11 4 0 28 100.00 27320104303 25.01.017 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KOSABI-FURUS, RATNAGIRI 41 41 19 18 4 0 41 100.00 27320115803 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 2 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. -

Folk Theatre in Goa: a Critical Study of Select Forms Thesis

FOLK THEATRE IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECT FORMS THESIS Submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY For the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar Under the Guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K. J. Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. January 2018 CERTIFICATE As required under the University Ordinance, OA-19.8 (viii), I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, submitted by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English has been completed under my guidance. The thesis is the record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to her by this or any other University. Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. Date: i DECLARATION As required under the University Ordinance OA-19.8 (v), I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley, Professor of English (Retd.),Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in the thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to me, by this or any other University. Ms. -

“Re-Rigging” the Vedas: Examining the Effects of Changing Education and Purity Standards and Political Influence on the Contemporary Hindu Priesthood

“Re-Rigging” the Vedas: Examining the Effects of Changing Education and Purity Standards and Political Influence on the Contemporary Hindu Priesthood Christine Shanaberger Religious Studies RST 490 David McMahan, advisor Submitted: May 4, 2006 Graduated: May 13, 2006 1 Introduction In the academic study of religion, we are often given impressions about a tradition that are textually accurate, but do not directly correspond with its practice amongst its devotees. Hinduism is one such tradition where scholarly work has been predominately textual and quite removed from practices “on the ground.” While most scholars recognize that many indigenous Hindu practices do not conform to the Brahmanical standards described in ancient Hindu texts, there has only recently been a movement to study the “popular,” non-Brahmanical traditions, let alone to look at the Brahmanical practice and its variance with ancient conventions. I have personally experienced this inconsistency between textual and popular Hinduism. After spending a semester in India, I quickly realized that my background in the study of Hinduism was, indeed, merely a background. I found myself re-learning aspects of the tradition and theology that I thought I had already understood and redefining the meaning of many practices as I learned of their practical application. Most importantly, I discovered that Hindu practices and beliefs are so diverse that I could never anticipate who would believe or practice in what way. I met many “modernized” Indians who both ignored and retained many orthodox elements of their traditions, priests who were unaware of even the most basic elements of Hindu mythology, and devotees who had no qualms engaging in both orthodox Brahmin and quite unorthodox non-Brahmin religious practices. -

Stylesheet IJIE

IRIE International Review of Information Ethics Vol. 9 (08/2008) Patheneni Sivaswaroop: The Internet and Hinduism – A Study Abstract: This paper discusses some results of a sample study on how Hindus are using the internet for religious pur- poses comparing their on-line and off-line religious activities. The behaviour is similar to those reported for different religions from different countries. But it is found that 74% of the sample pray daily, where only 16% go daily to a local temple. This seems to be a major difference between Western and the Hindu religions. In Hinduism going to temple is secondary, as each Hindu house has generally a pooja (room/corner). The survey reports and the uses of the internet by Hindus as well as whether the internet increases religious tolerance or hatred. Agenda: Introduction............................................................................................................................................ 35 Hinduism in the present context............................................................................................................... 36 The Sample ............................................................................................................................................ 37 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................ 39 Author: Dr P. Sivaswaroop, Deputy Director Regional Centre, Indira Gandhi National Open University, Himayat Nagar, Hyderabad – 500 029. In-