Philip Freneau and His Qircle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources and Bibliography

Sources and Bibliography AMERICAN EDEN David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic Victoria Johnson Liveright | W. W. Norton & Co., 2018 Note: The titles and dates of the historical newspapers and periodicals I have consulted regarding particular events and people appear in the endnotes to AMERICAN EDEN. Manuscript Collections Consulted American Philosophical Society Barton-Delafield Papers Caspar Wistar Papers Catharine Wistar Bache Papers Bache Family Papers David Hosack Correspondence David Hosack Letters and Papers Peale Family Papers Archives nationales de France (Pierrefitte-sur-Seine) Muséum d’histoire naturelle, Série AJ/15 Bristol (England) Archives Sharples Family Papers Columbia University, A.C. Long Health Sciences Center, Archives and Special Collections Trustees’ Minutes, College of Physicians and Surgeons Student Notes on Hosack Lectures, 1815-1828 Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library Papers of Aaron Burr (27 microfilm reels) Columbia College Records (1750-1861) Buildings and Grounds Collection DeWitt Clinton Papers John Church Hamilton Papers Historical Photograph Collections, Series VII: Buildings and Grounds Trustees’ Minutes, Columbia College 1 Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library David Hosack Papers Harvard University, Botany Libraries Jane Loring Gray Autograph Collection Historical Society of Pennsylvania Rush Family Papers, Series I: Benjamin Rush Papers Gratz Collection Library of Congress, Washington, DC Thomas Law Papers James Thacher -

NEWSPAPERS and PERIODICALS FINDING AID Albert H

Page 1 of 7 NEWSPAPERS AND PERIODICALS FINDING AID Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection Newspapers and Periodicals Listed Chronologically: 1789 The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 10 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Long two-page debate about the permanent residence of the Federal government: banks of the Susquehanna River vs. the banks of the Potomac River. AS 493. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 25 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Continues to cover the debate about future permanent seat of the Federal Government, ruling out New York. Also discusses the salaries of federal judges. AS 499. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 28 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. AS 947. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 8 Oct. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Archives of the United States are established. AS 501. 1790 Gazette of the United States, New York City, 17 July 1790. Report on debate in Congress over amending the act establishing the federal city. Also includes the Act of Congress passed 4 January 1790 to establish the District of Columbia. AS 864. Columbia Centinel, Boston, 3 Nov. 1790. Published by Benjamin Russell. Page 2 includes a description of President George Washington and local gentlemen surveying the land adjacent to the Potomac River to fix the proper situation for the Federal City. AS 944. 1791 Gazette of the United States, Philadelphia, 8 October, 1791. Publisher: John Fenno. Describes the location of the District of Columbia on the Potomac River. -

Life Cut Short: Hamilton's Hair and the Art Of

Life Cut Short: Hamilton’s Hair and the Art of Mourning Jewelry December 20, 2019 – May 10, 2020 Selected PR Images As a token of affection or a memorial to a lost loved one, human hair has long been incorporated into objects of adornment. Life Cut Short looks at the history of hair and mourning jewelry through a display of approximately 60 bracelets, earrings, brooches, and other accessories from New-York Historical’s collection. Also on display: miniaturist John Ramage’s hair working tools and ivory sample cards with selections of hair designs, period advertisements, instruction and etiquette books, magazines, and illustrations of hair-braiding patterns. Unidentified maker Mourning ring containing lock of Alexander Hamilton’s hair presented to Nathaniel Pendleton by Elizabeth Hamilton, 1805 Gold, hair New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mr. B. Pendleton Rogers, 1961.5a Hair from prominent figures was collected and given to friends and close associates. This ring contains the hair of Alexander Hamilton. While on his deathbed, Hamilton’s wife Elizabeth clipped locks of his hair to preserve as mementoes for herself and her husband’s close friends. Letter from Elizabeth Hamilton to Nathaniel Pendleton, June 21, 1805, regarding presentation of the ring Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society In 1805, Elizabeth Hamilton presented the ring above to Nathaniel Pendleton, one of the executors of Hamilton’s will and the statesman’s second in the famous duel. In this letter, she requests that Pendleton wear the ring “in Remembrance of your beloved friend a precious Lock of his hair.” John Ramage (ca. -

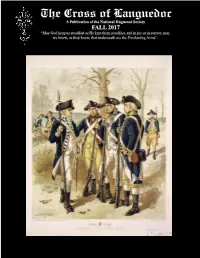

FALL 2017 “May God Keep Us Steadfast As He Kept Them Steadfast, and in Joy Or in Sorrow, May We Know, As They Knew, That Underneath Are the Everlasting Arms”

The Cross of Languedoc A Publication of the National Huguenot Society FALL 2017 “May God keep us steadfast as He kept them steadfast, and in joy or in sorrow, may we know, as they knew, that underneath are the Everlasting Arms”. COVER FEATURE – HUGUENOTS IN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR By Editor Janice Murphy Lorenz, J.D. Cover Feature image: Infantry: Continental Army, 1779-1783, artist Henry Alexander Ogden; lithograph by G. H. Buek & Col, NY, c1897; edited by Janice Murphy Lorenz. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Expired copyright by Brig. Gen’l S.B. Holabird, Qr. Master Gen’l, U.S.A. Three of the most important values in Huguenot culture are freedom of conscience, patriotism, and courage of conviction. That is why so many men and women of Huguenot descent are prominent in the annals of early American history. One example is the many different ways in which Huguenots contributed to the American cause in the Revolutionary War. As might be imagined from regarding cover lithograph of four soldiers, which depicts the uniforms and weapons used during the period 1779 to 1783, fathers, sons, brothers and cousins fought in the war on both sides, according to their conscience. The following article from 1894 clearly emphasizes the Huguenots’ patriotic service to America’s freedom, while mentioning that some were Loyalists, too. On later pages, you will find a list prepared by Genealogist General Nancy Wright Brennan of approved Huguenot ancestors and their descendants whose patriotic service has been recognized in the patriots database maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). -

Jefferson and Franklin

Jefferson and Franklin ITH the exception of Washington and Lincoln, no two men in American history have had more books written about W them or have been more widely discussed than Jefferson and Franklin. This is particularly true of Jefferson, who seems to have succeeded in having not only bitter critics but also admiring friends. In any event, anything that can be contributed to the under- standing of their lives is important; if, however, something is dis- covered that affects them both, it has a twofold significance. It is for this reason that I wish to direct attention to a paragraph in Jefferson's "Anas." As may not be generally understood, the "Anas" were simply notes written by Jefferson contemporaneously with the events de- scribed and revised eighteen years later. For this unfortunate name, the simpler title "Jeffersoniana" might well have been substituted. Curiously enough there is nothing in Jefferson's life which has been more severely criticized than these "Anas." Morse, a great admirer of Jefferson, takes occasion to say: "Most unfortunately for his own good fame, Jefferson allowed himself to be drawn by this feud into the preparation of the famous 'Anas/ His friends have hardly dared to undertake a defense of those terrible records."1 James Truslow Adams, discussing the same subject, remarks that the "Anas" are "unreliable as historical evidence."2 Another biographer, Curtis, states that these notes "will always be a cloud upon his integrity of purpose; and, as is always the case, his spitefulness toward them injured him more than it injured Hamilton or Washington."3 I am not at all in accord with these conclusions. -

Washington Irving's Use of Historical Sources in the Knickerbocker History of New York

WASHINGTON IRVING’S USE OF HISTORICAL SOURCES IN THE KNICKERBOCKER. HISTORY OF NEW YORK Thesis for the Degree of M. A. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY DONNA ROSE CASELLA KERN 1977 IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII 3129301591 2649 WASHINGTON IRVING'S USE OF HISTORICAL SOURCES IN THE KNICKERBOCKER HISTORY OF NEW YORK By Donna Rose Casella Kern A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English 1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . CHAPTER I A Survey of Criticism . CHAPTER II Inspiration and Initial Sources . 15 CHAPTER III Irving's Major Sources William Smith Jr. 22 CHAPTER IV Two Valuable Sources: Charlevoix and Hazard . 33 CHAPTER V Other Sources 0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 Al CONCLUSION 0 O C O O O O O O O O O O O 0 O O O O O 0 53 APPENDIX A Samuel Mitchell's A Pigture 9: New York and Washington Irving's The Knickerbocker Histgrx of New York 0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o c o o o o 0 56 APPENDIX B The Legend of St. Nicholas . 58 APPENDIX C The Controversial Dates . 61 APPENDIX D The B00k'S Topical Satire 0 o o o o o o o o o o 0 6A APPENDIX E Hell Gate 0 0.0 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 66 APPENDIX F Some Minor Sources . -

October 9 Update 2FALL 2018 SYLLABUS Engl E 182A POETRY

Poetry in America: From the Mayflower Through Emerson Harvard Extension School: ENGL E-182a (CRN 15383) SYLLABUS | Fall 2018 COURSE TEAM Instructor Elisa New PhD, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, Harvard University Teaching Instructor Gillian Osborne, PhD ([email protected]) Teaching Fellows Field Brown, PhD candidate, Harvard University ([email protected]) Jacob Spencer, PhD, Harvard University ([email protected]) Course Manager Caitlin Ballotta Rajagopalan, Manager of Online Education, Poetry in America ([email protected]) ABOUT THIS COURSE This course, an installment of the multi-part Poetry in America series , covers American poetry in cultural context through the year 1850. The course begins with Puritan poets—some orthodox, some rebel spirits—who wrote and lived in early New England. Focusing on Anne Bradstreet, Edward Taylor, and Michael Wigglesworth, among others, we explore the interplay between mortal and immortal, Europe and wilderness, solitude and sociality in English North America. The second part of the course spans the poetry of America's early years, directly before and after the creation of the Republic. We examine the creation of a national identity through the lens of an emerging national literature, focusing on such poets as Phillis Wheatley, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edgar Allen Poe, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, among others. Distinguished guest discussants in this part of the course include writer Michael Pollan, economist Larry Summers, Vice President Al Gore, Mayor Tom Menino, and others. Many of the course segments have been filmed in historic places—at Cape Cod; on the Freedom Trail in Boston; in marshes, meadows, churches, and parlors, and at sites of Revolutionary War battle. -

What's in a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2019 What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795 Hannah M. Nolan University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Nolan, Hannah M., "What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795" (2019). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/2237 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nolan 1 Hannah Nolan History 408: Section 001 Final Draft: 12 December 2018 What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795 Mere months after Louis XVI met his end at the base of the National Razor in 1793, the guillotine appeared in Philadelphia. Made of paper and ink rather than the wood and steel of its Parisian counterpart, this blade did not threaten to turn the capital’s streets red or -

George Washington Was Perhaps in a More Petulant Mood Than

“A Genuine RepublicAn”: benjAmin FRAnklin bAche’s RemARks (1797), the FedeRAlists, And RepublicAn civic humAnism Arthur Scherr eorge Washington was perhaps in a more petulant mood than Gusual when he wrote of Benjamin Franklin Bache, Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, in 1797: “This man has celebrity in a certain way, for his calumnies are to be exceeded only by his impudence, and both stand unrivalled.” The ordinarily reserved ex-president had similarly commented four years earlier that the “publica- tions” in Philip Freneau’s National Gazette and Bache’s daily newspaper, the Philadelphia General Advertiser, founded in 1790, which added the noun Aurora to its title on November 8, 1794, were “outrages on common decency.” The new nation’s second First Lady, Abigail Adams, was hardly friendlier, denounc- ing Bache’s newspaper columns as a “specimen of Gall.” Her husband, President John Adams, likewise considered Bache’s anti-Federalist diatribes and abuse of Washington “diabolical.” Both seemed to have forgotten the bygone, cordial days in Paris during the American Revolution, when their son John Quincy, two years Bache’s senior, attended the Le Coeur boarding school pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 80, no. 2, 2013. Copyright © 2013 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.153.205 on Mon, 15 Apr 2019 13:25:50 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms pennsylvania history with “Benny” (family members also called him “Little Kingbird”). But the ordinarily dour John Quincy remembered. Offended that the Aurora had denounced his father’s choosing him U.S. -

The Federal Era

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED THIRTY-SEVEN The Federal Era WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to the two decades from the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 to the first Jefferson administration and the Louisiana Purchase, usually known to scholars as the Federal era. It saw the evolution of the United States from the uncertainties of the Confederation to the establishment of the Constitution and first federal government in 1787-89, through Washington’s two administrations and that of John Adams, and finally the Jeffersonian revolution of 1800 and the dramatic expansion of the United States. Notable items include a first edition of The Federalist; a collection of the treaties ending the Revolutionary conflict (1783); the first edition of the first American navigational guide, by Furlong (1796); the Virginia Resolutions of 1799; various important cartographical works by Norman and Mount & Page; a first edition of Benjamin’s Country Builder’s Assistant (1797); a set of Carey’s American Museum; and much more. Our catalogue 338 will be devoted to Western Americana. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues 331 Archives & Manuscripts, 332 French Americana, 333 Americana–Beginnings, 334 Recent Acquisitions in Americana, and 336 What I Like About the South; bulletins 41 Original Works of American Art, 42 Native Americans, 43 Cartography, and 44 Photography; e-lists (only available on our website) and many more topical lists. q A portion of our stock may be viewed at www.williamreesecompany.com. If you would like to receive e-mail notification when catalogues and lists are uploaded, please e-mail us at [email protected] or send us a fax, specifying whether you would like to receive the notifications in lieu of or in addition to paper catalogues. -

Philip Freneau - "A Poet of the American Revolution"………21

Contents Introduction……………………….……………………………………………...2 Chapter I Poets and Poetry during the American Revolution …………..…8 Chapter II Philip Freneau - "A Poet of the American Revolution"………21 Chapter III Literary analysis of Philip Freneau‘s poems………………….36 Chapter IV Using Philip Freneau‘s Poetry to Study a Foreign Language…..46 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………..57 The list of used literature………………………………………………………..59 1 Introduction In extraordinary session which was held in Samarqand in December 2010, I.A Karimov underlined that learning English language must be on the first plan of each young people as it is the main way of being on the equal line with young people of the developed countries, and teaching English must be on high level to prepare our youth as a competitive specialists in the world.. One of the prior tasks of development of Independent Uzbekistan suggested by the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan I. A. Karimov is the task of public education. The state first of all, must take care of the future generation. In his report I. A. Karimov paid great attention to foreign languages. With the adoption "About Education" in 1997 and "The national programme by training personnel" the additional measures and positive reforms were carried out at the universities of Uzbekistan. One of them is the department of "Uzbek and foreign languages". According to the Laws and Resolution of the Government directed to the improvement of teaching foreign languages, teachers of Uzbekistan work out a new program, syllabus taking into account the specialization of the universities. They reflect the link between the process of teaching and upbringing, include different types of independent work; special attention is paid to the development of communicative habit and skills so as the students could use foreign language in their practical, professional activity. -

The Legacy of Trauma in Collective Memory As Seen Through a Study of Evacuation Day

THE DAY NEW YORK FORGOT: THE LEGACY OF TRAUMA IN COLLECTIVE MEMORY AS SEEN THROUGH A STUDY OF EVACUATION DAY Cody Osterman A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2016 Committee: Andrew Schocket, Advisor Rebecca Mancuso ii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor On November 25 1783, the British evacuated New York City after occupying the city for seven-years during the American Revolution. As Washington and his troops marched into Manhattan to take command of the city, both those who fled New York, as Washington did in 1776, and those who endured the occupation joyously celebrated his return, which for them, marked the end of the Revolution. Each year from there on, the 25th of November was celebrated as a day that would later be titled Evacuation Day. This work analyzes how Evacuation Day was celebrated from 1783 to 1883. This study examines the reception to each year’s Evacuation Day celebration through a rhetorical analysis of local newspaper coverage of the event and argues that traumatic memory is very fragile and unless well-cultivated fails to transfer to from generation to generation—replaced instead with meaningless ritual and bombastic spectacle. iii To my parents, Howard and Cathy Osterman, without which none of this is possible. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank both members of my committee, Andrew Schocket and Rebecca Mancuso, for their support and feedback throughout this process. Working with these two scholars offered me the guidance and flexibility I needed to make this project possible.