What's in a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSPAPERS and PERIODICALS FINDING AID Albert H

Page 1 of 7 NEWSPAPERS AND PERIODICALS FINDING AID Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection Newspapers and Periodicals Listed Chronologically: 1789 The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 10 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Long two-page debate about the permanent residence of the Federal government: banks of the Susquehanna River vs. the banks of the Potomac River. AS 493. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 25 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Continues to cover the debate about future permanent seat of the Federal Government, ruling out New York. Also discusses the salaries of federal judges. AS 499. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 28 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. AS 947. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 8 Oct. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Archives of the United States are established. AS 501. 1790 Gazette of the United States, New York City, 17 July 1790. Report on debate in Congress over amending the act establishing the federal city. Also includes the Act of Congress passed 4 January 1790 to establish the District of Columbia. AS 864. Columbia Centinel, Boston, 3 Nov. 1790. Published by Benjamin Russell. Page 2 includes a description of President George Washington and local gentlemen surveying the land adjacent to the Potomac River to fix the proper situation for the Federal City. AS 944. 1791 Gazette of the United States, Philadelphia, 8 October, 1791. Publisher: John Fenno. Describes the location of the District of Columbia on the Potomac River. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

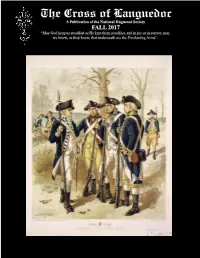

FALL 2017 “May God Keep Us Steadfast As He Kept Them Steadfast, and in Joy Or in Sorrow, May We Know, As They Knew, That Underneath Are the Everlasting Arms”

The Cross of Languedoc A Publication of the National Huguenot Society FALL 2017 “May God keep us steadfast as He kept them steadfast, and in joy or in sorrow, may we know, as they knew, that underneath are the Everlasting Arms”. COVER FEATURE – HUGUENOTS IN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR By Editor Janice Murphy Lorenz, J.D. Cover Feature image: Infantry: Continental Army, 1779-1783, artist Henry Alexander Ogden; lithograph by G. H. Buek & Col, NY, c1897; edited by Janice Murphy Lorenz. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Expired copyright by Brig. Gen’l S.B. Holabird, Qr. Master Gen’l, U.S.A. Three of the most important values in Huguenot culture are freedom of conscience, patriotism, and courage of conviction. That is why so many men and women of Huguenot descent are prominent in the annals of early American history. One example is the many different ways in which Huguenots contributed to the American cause in the Revolutionary War. As might be imagined from regarding cover lithograph of four soldiers, which depicts the uniforms and weapons used during the period 1779 to 1783, fathers, sons, brothers and cousins fought in the war on both sides, according to their conscience. The following article from 1894 clearly emphasizes the Huguenots’ patriotic service to America’s freedom, while mentioning that some were Loyalists, too. On later pages, you will find a list prepared by Genealogist General Nancy Wright Brennan of approved Huguenot ancestors and their descendants whose patriotic service has been recognized in the patriots database maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). -

Jefferson and Franklin

Jefferson and Franklin ITH the exception of Washington and Lincoln, no two men in American history have had more books written about W them or have been more widely discussed than Jefferson and Franklin. This is particularly true of Jefferson, who seems to have succeeded in having not only bitter critics but also admiring friends. In any event, anything that can be contributed to the under- standing of their lives is important; if, however, something is dis- covered that affects them both, it has a twofold significance. It is for this reason that I wish to direct attention to a paragraph in Jefferson's "Anas." As may not be generally understood, the "Anas" were simply notes written by Jefferson contemporaneously with the events de- scribed and revised eighteen years later. For this unfortunate name, the simpler title "Jeffersoniana" might well have been substituted. Curiously enough there is nothing in Jefferson's life which has been more severely criticized than these "Anas." Morse, a great admirer of Jefferson, takes occasion to say: "Most unfortunately for his own good fame, Jefferson allowed himself to be drawn by this feud into the preparation of the famous 'Anas/ His friends have hardly dared to undertake a defense of those terrible records."1 James Truslow Adams, discussing the same subject, remarks that the "Anas" are "unreliable as historical evidence."2 Another biographer, Curtis, states that these notes "will always be a cloud upon his integrity of purpose; and, as is always the case, his spitefulness toward them injured him more than it injured Hamilton or Washington."3 I am not at all in accord with these conclusions. -

Virginia Historical Society the CENTER for VIRGINIA HISTORY

Virginia Historical Society THE CENTER FOR VIRGINIA HISTORY ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2004 ANNUAL MEETING, 23 APRIL 2005 Annual Report for 2004 Introduction Charles F. Bryan, Jr. President and Chief Executive Officer he most notable public event of 2004 for the Virginia Historical Society was undoubtedly the groundbreaking ceremony on the first of TJuly for our building expansion. On that festive afternoon, we ushered in the latest chapter of growth and development for the VHS. By turning over a few shovelsful of earth, we began a construction project that will add much-needed programming, exhibition, and storage space to our Richmond headquarters. It was a grand occasion and a delight to see such a large crowd of friends and members come out to participate. The representative individuals who donned hard hats and wielded silver shovels for the formal ritual of begin- ning construction stood in for so many others who made the event possible. Indeed, if the groundbreaking was the most important public event of the year, it represented the culmination of a vast investment behind the scenes in forward thinking, planning, and financial commitment by members, staff, trustees, and friends. That effort will bear fruit in 2006 in a magnifi- cent new facility. To make it all happen, we directed much of our energy in 2004 to the 175th Anniversary Campaign–Home for History in order to reach the ambitious goal of $55 million. That effort is on track—and for that we can be grateful—but much work remains to be done. Moreover, we also need to continue to devote resources and talent to sustain the ongoing programs and activities of the VHS. -

Full Screen View

A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF STATE POLITICAL PARTY NEWSPAPERS by Robert Eddy Jednak A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Social Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August, 1970 A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF STATE POLITICAL PARTY NEWSPAPERS by Robert Eddy Jeanak This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Dr, Robert J. Huckshorn, Department of Political Science, and has been approved by the members of his super visory committee, It was submitted to the faculty of the College of Social Science and ~vas accepted in partial fulfill ment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, (Chairman, D College of Social Science) (Date) TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. STATE POLITICAL NEWSPAPERS: EVERPRESENT AND LITTLE KNOHN • • • • • • . 1 II. FIVE PROPOSITIONS TliAT TEST THE IMPORT OF THE STATE POLITICAL PARTY NEWSPAPER . 8 III. THE FINDINGS OF CONTENT ANALYSIS FOR PROPOSITIONS I-V • • • • • • . 21 IV. A TUfE ANALYSIS OF SIX SELECTED STATE POLITICAL PARTY NE\-lSPAPERS . 36 APPENDICES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 54 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 61 CHAPTER I STATE POLITICAL NEWSPAPERS: EVERPRESENT AND LITTLE KNOWN Thus launched as we are in an ocean of news, In hopes that your pleasure our pains will repay, All honest endeavors the author will use To furnish a feast for the grave and the gay; At least he'll essay such a track to pursue, That the \-mrld shall approve---and his ne~11s shall be true.l ~Uth the above words Philip Freneau, a poet, \vriter, and journalist of renown during the latter part of the 18th century, summarized the conduct of the political press in the October 31, 1791 issue of The National Gazette. -

Honor, Secession, and Civil War”

The 2004 JAMES PINCKNEY HARRISON LECTURES IN HISTORY Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History Monday, March 29, 2004, 4:30 PM Andrews Hall 101 “Honor, Secession, and Civil War” © Bertram Wyatt-Brown The great Virginia historian and biographer Douglas Southall Freeman may have venerated Robert E. Lee beyond all basis. Yet in 1937, he asked a still unresolved question. The Richmond Pulitzer-Prize winner wondered why a rational calculation of risks, as war clouds gathered, received so little notice in the under- populated, industrially ill-equipped South. The secessionists’ saber-rattling of 1859-61 might disclose,” Freeman is quoted to exclaim, “a clinically perfect case in the psychosis of war.”1 He was reflecting the pacifistic mood of the interwar period. The popular scholarship of the day attributed the crisis to a “blundering” antebellum “generation.” Americans fell into the mess of war, so the refrain went, because its leaders were incompetent, demagogic, and uncourageous. Freeman’s comment itself reflects that orientation by defining calls to arms as “psychotic.” Well, that idea died, and other explanations quickly filled the void. Nowadays the reasons for war come down to two antithetical theories. Neo- Confederates claim that a stout defense of southern “liberty” and constitutional state-rights drew thousands to initiate a war against Northern Aggression, as it is often phrased in such circles. Most academic historians, however, propose the fundamental issue of slavery, without which, they contend, the nation would never have resorted to a military coercions.2 A third possibility springs to mind. In a sense, it embraces both of these but alters their character, too. -

Partisanship in Perspective

Partisanship in Perspective Pietro S. Nivola ommentators and politicians from both ends of the C spectrum frequently lament the state of American party politics. Our elected leaders are said to have grown exceptionally polarized — a change that, the critics argue, has led to a dysfunctional government. Last June, for example, House Republican leader John Boehner decried what he called the Obama administration’s “harsh” and “hyper-partisan” rhetoric. In Boehner’s view, the president’s hostility toward Republicans is a smokescreen to obscure Obama’s policy failures, and “diminishes the office of the president.” Meanwhile, President Obama himself has complained that Washington is a city in the grip of partisan passions, and so is failing to do the work the American people expect. “I don’t think they want more gridlock,” Obama told Republican members of Congress last year. “I don’t think they want more partisanship; I don’t think they want more obstruc- tion.” In his 2006 book, The Audacity of Hope, Obama yearned for what he called a “time before the fall, a golden age in Washington when, regardless of which party was in power, civility reigned and government worked.” The case against partisan polarization generally consists of three elements. First, there is the claim that polarization has intensified sig- nificantly over the past 30 years. Second, there is the argument that this heightened partisanship imperils sound and durable public policy, perhaps even the very health of the polity. And third, there is the impres- sion that polarized parties are somehow fundamentally alien to our form of government, and that partisans’ behavior would have surprised, even shocked, the founding fathers. -

George Chaplin: W. Sprague Holden: Newbold Noyes: Howard 1(. Smith

Ieman• orts June 1971 George Chaplin: Jefferson and The Press W. Sprague Holden: The Big Ones of Australian Journalism Newbold Noyes: Ethics-What ASNE Is All About Howard 1(. Smith: The Challenge of Reporting a Changing World NEW CLASS OF NIEMAN FELLOWS APPOINTED NiemanReports VOL. XXV, No. 2 Louis M. Lyons, Editor Emeritus June 1971 -Dwight E. Sargent, Editor- -Tenney K. Lehman, Executive Editor- Editorial Board of the Society of Nieman Fellows Jack Bass Sylvan Meyer Roy M. Fisher Ray Jenkins The Charlotte Observer Miami News University of Missouri Alabama Journal George E. Amick, Jr. Robert Lasch Robert B. Frazier John Strohmeyer Trenton Times St. Louis Post-Dispatch Eugene Register-Guard Bethlehem Globe-Times William J. Woestendiek Robert Giles John J. Zakarian E. J. Paxton, Jr. Colorado Springs Sun Knight Newspapers Boston Herald Traveler Paducah Sun-Democrat Eduardo D. Lachica Smith Hempstone, Jr. Rebecca Gross Harry T. Montgomery The Philippines Herald Washington Star Lock Haven Express Associated Press James N. Standard George Chaplin Alan Barth David Kraslow The Daily Oklahoman Honolulu Advertiser Washington Post Los Angeles Times Published quarterly by the Society of Nieman Fellows from 48 Trowbridge Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138. Subscription $5 a year. Third class postage paid at Boston, Mass. "Liberty will have died a little" By Archibald Cox "Liberty will have died a little," said Harvard Law allowed to speak at Harvard-Fidel Castro, the late Mal School Prof. Archibald Cox, in pleading from the stage colm X, George Wallace, William Kunstler, and others. of Sanders Theater, Mar. 26, that radical students and Last year, in this very building, speeches were made for ex-students of Harvard permit a teach-in sponsored by physical obstruction of University activities. -

Read the Fall 2020 Newsletter

FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NEWS FROM FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NONPROFIT ORG. 412 South Cherry Street U.S. POSTAGE Richmond, Virginia 23220 PAID PERMIT NO. 671 23232 A Gateway Into History WWW.HOLLYWOODCEMETERY.ORG FALL 2020 • VOLUME 11, NUMBER 2 Follow the Blue Line A Special Guide to Hollywood’s Highlights ith over 135 acres of rolling hills, winding paths, and thousands of gravesites, Hollywood can be overwhelmingW to visitors. But many can find an easy introduction to the cemetery by following a simple blue line, painted on the right side of the road. “The blue line was first implemented in 1992 as a guide to help visitors follow the tour map to find the graves of notables who are buried here. The blue line on the roadway corresponds with the one on our tour map,” said David Gilliam, General Manager of Hollywood Cemetery. Rolling hills of Confederate fallen. From there, visitors veer right to tour the Confederate Section. Simple white tombstones lie in the shadows of Hollywood’s 90-foot granite pyramid, completed in 1869—a memorial to the 18,000 Confederate soldiers buried nearby. (And sharp-eyed visitors may discover a smaller, replica pyramid closer to the river for Leslie Dove, who died at age 17 at Gettysburg). After circling this area, the blue line continues along Western Avenue, and then to scenic Ellis Avenue, which overlooks a valley. Here, two notables have gravesites A young girl’s four-legged guardian. right next to each other: Confederate General J.E.B. The approximately 2 ¼-mile route begins at Hollywood’s Stuart and Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Ellen entrance. -

October 9 Update 2FALL 2018 SYLLABUS Engl E 182A POETRY

Poetry in America: From the Mayflower Through Emerson Harvard Extension School: ENGL E-182a (CRN 15383) SYLLABUS | Fall 2018 COURSE TEAM Instructor Elisa New PhD, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, Harvard University Teaching Instructor Gillian Osborne, PhD ([email protected]) Teaching Fellows Field Brown, PhD candidate, Harvard University ([email protected]) Jacob Spencer, PhD, Harvard University ([email protected]) Course Manager Caitlin Ballotta Rajagopalan, Manager of Online Education, Poetry in America ([email protected]) ABOUT THIS COURSE This course, an installment of the multi-part Poetry in America series , covers American poetry in cultural context through the year 1850. The course begins with Puritan poets—some orthodox, some rebel spirits—who wrote and lived in early New England. Focusing on Anne Bradstreet, Edward Taylor, and Michael Wigglesworth, among others, we explore the interplay between mortal and immortal, Europe and wilderness, solitude and sociality in English North America. The second part of the course spans the poetry of America's early years, directly before and after the creation of the Republic. We examine the creation of a national identity through the lens of an emerging national literature, focusing on such poets as Phillis Wheatley, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edgar Allen Poe, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, among others. Distinguished guest discussants in this part of the course include writer Michael Pollan, economist Larry Summers, Vice President Al Gore, Mayor Tom Menino, and others. Many of the course segments have been filmed in historic places—at Cape Cod; on the Freedom Trail in Boston; in marshes, meadows, churches, and parlors, and at sites of Revolutionary War battle. -

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection 1839.6.681 Book John Marshall The Writings of Chief Justice Marshall on the Federal 1839 GCM-KTM Constitution 1845.6.878 Book Unknown The Proverbs and other Remarkable Sayings of Solomon 1845 GCM-KTM 1850.6.407 Book Ik Marvel Reveries of A Bachelor or a Book of the Heart 1850 GCM-KTM The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, to the 1857.6.920 Book Joseph Butler 1857 GCM-KTM Constitution and Course of Nature 1859.6.1083 Book George Eliot Adam Bede 1859 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.1 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.2 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.1 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.2 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.162 Book Charles Dickens Great Expectations: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.163 Book Charles Dickens Christmas Books: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.1 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.2 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1871.6.359 Book James Russell Lowell Literary Essays 1871 GCM-KTM 1876.6.