Honor, Secession, and Civil War”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Virginia Historical Society the CENTER for VIRGINIA HISTORY

Virginia Historical Society THE CENTER FOR VIRGINIA HISTORY ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2004 ANNUAL MEETING, 23 APRIL 2005 Annual Report for 2004 Introduction Charles F. Bryan, Jr. President and Chief Executive Officer he most notable public event of 2004 for the Virginia Historical Society was undoubtedly the groundbreaking ceremony on the first of TJuly for our building expansion. On that festive afternoon, we ushered in the latest chapter of growth and development for the VHS. By turning over a few shovelsful of earth, we began a construction project that will add much-needed programming, exhibition, and storage space to our Richmond headquarters. It was a grand occasion and a delight to see such a large crowd of friends and members come out to participate. The representative individuals who donned hard hats and wielded silver shovels for the formal ritual of begin- ning construction stood in for so many others who made the event possible. Indeed, if the groundbreaking was the most important public event of the year, it represented the culmination of a vast investment behind the scenes in forward thinking, planning, and financial commitment by members, staff, trustees, and friends. That effort will bear fruit in 2006 in a magnifi- cent new facility. To make it all happen, we directed much of our energy in 2004 to the 175th Anniversary Campaign–Home for History in order to reach the ambitious goal of $55 million. That effort is on track—and for that we can be grateful—but much work remains to be done. Moreover, we also need to continue to devote resources and talent to sustain the ongoing programs and activities of the VHS. -

Read the Fall 2020 Newsletter

FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NEWS FROM FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NONPROFIT ORG. 412 South Cherry Street U.S. POSTAGE Richmond, Virginia 23220 PAID PERMIT NO. 671 23232 A Gateway Into History WWW.HOLLYWOODCEMETERY.ORG FALL 2020 • VOLUME 11, NUMBER 2 Follow the Blue Line A Special Guide to Hollywood’s Highlights ith over 135 acres of rolling hills, winding paths, and thousands of gravesites, Hollywood can be overwhelmingW to visitors. But many can find an easy introduction to the cemetery by following a simple blue line, painted on the right side of the road. “The blue line was first implemented in 1992 as a guide to help visitors follow the tour map to find the graves of notables who are buried here. The blue line on the roadway corresponds with the one on our tour map,” said David Gilliam, General Manager of Hollywood Cemetery. Rolling hills of Confederate fallen. From there, visitors veer right to tour the Confederate Section. Simple white tombstones lie in the shadows of Hollywood’s 90-foot granite pyramid, completed in 1869—a memorial to the 18,000 Confederate soldiers buried nearby. (And sharp-eyed visitors may discover a smaller, replica pyramid closer to the river for Leslie Dove, who died at age 17 at Gettysburg). After circling this area, the blue line continues along Western Avenue, and then to scenic Ellis Avenue, which overlooks a valley. Here, two notables have gravesites A young girl’s four-legged guardian. right next to each other: Confederate General J.E.B. The approximately 2 ¼-mile route begins at Hollywood’s Stuart and Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Ellen entrance. -

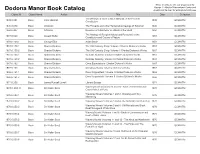

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection 1839.6.681 Book John Marshall The Writings of Chief Justice Marshall on the Federal 1839 GCM-KTM Constitution 1845.6.878 Book Unknown The Proverbs and other Remarkable Sayings of Solomon 1845 GCM-KTM 1850.6.407 Book Ik Marvel Reveries of A Bachelor or a Book of the Heart 1850 GCM-KTM The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, to the 1857.6.920 Book Joseph Butler 1857 GCM-KTM Constitution and Course of Nature 1859.6.1083 Book George Eliot Adam Bede 1859 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.1 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.2 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.1 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.2 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.162 Book Charles Dickens Great Expectations: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.163 Book Charles Dickens Christmas Books: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.1 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.2 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1871.6.359 Book James Russell Lowell Literary Essays 1871 GCM-KTM 1876.6. -

What's in a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2019 What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795 Hannah M. Nolan University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Nolan, Hannah M., "What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795" (2019). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/2237 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nolan 1 Hannah Nolan History 408: Section 001 Final Draft: 12 December 2018 What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795 Mere months after Louis XVI met his end at the base of the National Razor in 1793, the guillotine appeared in Philadelphia. Made of paper and ink rather than the wood and steel of its Parisian counterpart, this blade did not threaten to turn the capital’s streets red or -

Gallagher C.V.Pdf

Gary William Gallagher Corcoran Department of History P.O. Box 400180 423 Nau Hall University of Virginia Charlottesville, Virginia 22904-4180 Telephone: (434) 924-6908 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., M.A., University of Texas at Austin, 1982, 1977 B.A., Adams State College, 1972 CAREER John L. Nau III Professor in the History of the American Civil War, University of Virginia, 1999- ; Director, John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History, 2015- Professor, Department of History, University of Virginia, 1998-99 Professor, Department of History, Pennsylvania State University, 1991-98 (Head of Department, January 1991-June 1995) Associate Professor, Pennsylvania State University, 1989-1991 Assistant Professor, Pennsylvania State University, 1986-1989 Visiting Lecturer, Department of History, University of Texas at Austin, Spring 1986 Archivist, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, National Archives and Records Administration, 1977-1986 PUBLICATIONS I. Authored Books Becoming Confederates: Paths to a New National Loyalty. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013. The Union War. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011. (Winner of 2012 Tom Watson Brown Book Prize, 2012 Laney Prize, 2011 Eugene Feit Award in Civil War Studies; New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice) Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. Lee and His Army in Confederate History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. (A collection of 8 of my essays--7 revised versions of earlier pieces and 1 written for this book) The American Civil War: The War in the East 1861-May 1863. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Art and Life in America by Oliver W. Larkin Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum | Bush-Reisinger Museum | Arthur M. Sackler Museum. In this allegorical portrait, America is personified as a white marble goddess. Dressed in classical attire and crowned with thirteen stars representing the original thirteen colonies, the figure gives form to associations Americans drew between their democracy and the ancient Greek and Roman republics. Like most nineteenth-century American marble sculptures, America is the product of many hands. Powers, who worked in Florence, modeled the bust in plaster and then commissioned a team of Italian carvers to transform his model into a full-scale work. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who visited Powers’s studio in 1858, captured this division of labor with some irony in his novel The Marble Faun: “The sculptor has but to present these men with a plaster cast . and, in due time, without the necessity of his touching the work, he will see before him the statue that is to make him renowned.” Identification and Creation Object Number 1958.180 People Hiram Powers, American (Woodstock, NY 1805 - 1873 Florence, Italy) Title America Other Titles Former Title: Liberty Classification Sculpture Work Type sculpture Date 1854 Places Creation Place: North America, United States Culture American Persistent Link https://hvrd.art/o/228516 Location Level 2, Room 2100, European and American Art, 17th–19th century, Centuries of Tradition, Changing Times: Art for an Uncertain Age. Signed: on back: H. Powers Sculp. Henry T. Tuckerman, Book of the Artists: American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists, Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America , Putnam (New York, NY, 1867), p. -

A Monograph by MAJOR Gregory W. Mclean U.S. Army School Of

A Monograph by MAJOR Gregory W. McLean U.S. Army School of Advanced Military Studies United States Army Command and General Staff College Fort Leavenworth, Kansas AY 2012-001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-01 88}, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of lew, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 12. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From- To) 17-05-2012 Master's Thesis JUL 2011- MAY 2012 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Sa. CONTRACT NUMBER Leadership Principles for the new ADP 6-22 Sb. GRANT NUMBER Sc. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) Sd. PROJECT NUMBER MAJOR Gregory W. Mclean/ Se. TASK NUMBER Sf. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORG REPORT U.S. Army Command and General Staff College NUMBER ATTN: ATZL-SWD-GD Fort Leavenworth, KS 66027-2301 9. -

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS in LETTERS © by Larry James

PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS IN LETTERS © by Larry James Gianakos Fiction 1917 no award *1918 Ernest Poole, His Family (Macmillan Co.; 320 pgs.; bound in blue cloth boards, gilt stamped on front cover and spine; full [embracing front panel, spine, and back panel] jacket illustration depicting New York City buildings by E. C.Caswell); published May 16, 1917; $1.50; three copies, two with the stunning dust jacket, now almost exotic in its rarity, with the front flap reading: “Just as THE HARBOR was the story of a constantly changing life out upon the fringe of the city, along its wharves, among its ships, so the story of Roger Gale’s family pictures the growth of a generation out of the embers of the old in the ceaselessly changing heart of New York. How Roger’s three daughters grew into the maturity of their several lives, each one so different, Mr. Poole tells with strong and compelling beauty, touching with deep, whole-hearted conviction some of the most vital problems of our modern way of living!the home, motherhood, children, the school; all of them seen through the realization, which Roger’s dying wife made clear to him, that whatever life may bring, ‘we will live on in our children’s lives.’ The old Gale house down-town is a little fragment of a past generation existing somehow beneath the towering apartments and office-buildings of the altered city. Roger will be remembered when other figures in modern literature have been forgotten, gazing out of his window at the lights of some near-by dwelling lifting high above his home, thinking -

October 2015 (773) 774-6781

4 The Civil War Round Table Grapeshot Schimmelfennig Boutique Sixty plus years of audio recordings of CWRT lectures by distinguished histori- Bulletin ans are available and can be purchased Board THE CIVIL WAR ROUND TABLE in CD format. For pricing and a lec- Founded December 3, 1940 ture list, please contact Hal Ardell at [email protected] or phone him at Volume LXXVI, Number 2 Chicago, Illinois October 2015 (773) 774-6781. Future Meetings is presented Each meeting features a book raffle, with Regular meetings are held at the Nevins-Freeman Address The Kankakee Civil War proceeds going to battlefield preserva- Holiday Inn O’Hare, the second Fri- Dennis Frye on to esteemed Symposium will be held October tion. There is also a silent auction for day of each month, unless otherwise John Brown: The Spark That historian Dennis 10th at the Kankakee Community books donated by Ralph Newman and indicated. Ignited the War Frye. College. Among the speakers is our others, again with proceeds benefiting battlefield preservation. Nov. 13: Philip Leigh on “Trading by Bruce Allardice Dennis E. Frye is own Rob Girardi, who will present with the Enemy” “The Real War Never Got into the Dramatic and divisive words define the Chief Historian at Harpers Ferry Dec. 11: Dave Keller on History Books.” Rob will speak at More Upcoming Civil War Events 745TH REGULAR John Brown. Martyr or madman? National Historical Park. Writer, “Camp Douglas” lecturer, guide, and preservationist, the Twin Cities CWRT Oct. 20th, Oct. 2nd, Northern Illinois CWRT: MEETING Saint or the Devil? Terrorist or Jan. -

Books Organized by Author's First Name

ID # Title Author Year Published Shelf Accession # 2097 Masterpieces of the Centennial VOL 1 1876 E2 496 2896 Masterpieces of the Centennial VOL 2 1876 E2 496 3694 Masterpieces of the Centennial VOL 3 1876 E2 496 331 Address of Anthony M. Hance Anthony M. Hance 1911 P4 1902 Godey's Ladies Book-Vol.XXVIII Sarah J. Hale 1844 G1 1805 2713 Harper's Magazine-Vol.IIDec1850-May1851 2 Copies G2 2261 3511 Harper's Magazine-Vol.IIDec1850-May1851 2 Copies G2 2261 Montgomery County Town and Country Living 22001-2002 2001, 2002 S7 2510 Island of Life A Clergyman 1862 SR2 2635 The child's bible a Lady of Cincinati 1835 SR3 1542 The Church of Christ A Layman 1907 F5 2462 288 The Philadelphia Bank 1803-1903 A Stockholder 1903 P4 2719 2254 history of allegheny county a warner and co 1889 F2 2895 3980 Atlas A. H. Mueller 1909 ws1 2053 Old Glasas European and American A. Hudson Moore 1924 G5 2574 4162 National Fifth Reader A. S. Barnes and Company 1875 SR2 2696 Monument ot the Memory of Henry Clay A.H. Carrier 1859 H1 2564 950 Pennsylvania's Best A.H. Carstens 1960 C1 1836 3979 North Penn Atlas 1916 A.H. Mueller 1916 ws1 1552 Zinzendorf: The Ecumenical Pioneer A.J. Lewis 1962 F5 2761 678 The Life and Times of Cotton Mather A.P. Marvin 1892 H6 559 2439 Davie's Elementary algaebr A.S. Barnes and Burr 1859 SR 1 4086 barnes new national fourth reader a.s. barnes and co 1884 SR1 2506 New National Fifth Reader A.S. -

Taming the Tar Heel Department: D.H

Taming the Tar Heel Department: D.H. Hill and the Challenges of Operational-Level Command during the American Civil War A Monograph by MAJ Brit K. Erslev U.S. Army School of Advanced Military Studies United States Army Command and General Staff College Fort Leavenworth, Kansas AY 2011 Approved for Public Release; Distribution is Unlimited Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 074-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED blank) 12-05-2011 SAMS Monograph, JUN 2010-MAY 2011 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Taming the Tar Heel Department: D.H. Hill and the Challenges of Operational- Level Command during the American Civil War 6. AUTHOR(S) Major Brit K. Erslev 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS) REPORT NUMBER 250 Gibbon Avenue Fort Leavenworth, KS 66027-2134 9. SPONSORING / MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING / MONITORING AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 11.