The Importance of Feeling English: American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

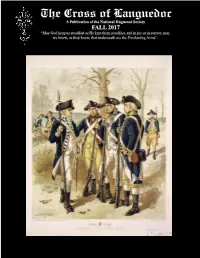

FALL 2017 “May God Keep Us Steadfast As He Kept Them Steadfast, and in Joy Or in Sorrow, May We Know, As They Knew, That Underneath Are the Everlasting Arms”

The Cross of Languedoc A Publication of the National Huguenot Society FALL 2017 “May God keep us steadfast as He kept them steadfast, and in joy or in sorrow, may we know, as they knew, that underneath are the Everlasting Arms”. COVER FEATURE – HUGUENOTS IN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR By Editor Janice Murphy Lorenz, J.D. Cover Feature image: Infantry: Continental Army, 1779-1783, artist Henry Alexander Ogden; lithograph by G. H. Buek & Col, NY, c1897; edited by Janice Murphy Lorenz. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Expired copyright by Brig. Gen’l S.B. Holabird, Qr. Master Gen’l, U.S.A. Three of the most important values in Huguenot culture are freedom of conscience, patriotism, and courage of conviction. That is why so many men and women of Huguenot descent are prominent in the annals of early American history. One example is the many different ways in which Huguenots contributed to the American cause in the Revolutionary War. As might be imagined from regarding cover lithograph of four soldiers, which depicts the uniforms and weapons used during the period 1779 to 1783, fathers, sons, brothers and cousins fought in the war on both sides, according to their conscience. The following article from 1894 clearly emphasizes the Huguenots’ patriotic service to America’s freedom, while mentioning that some were Loyalists, too. On later pages, you will find a list prepared by Genealogist General Nancy Wright Brennan of approved Huguenot ancestors and their descendants whose patriotic service has been recognized in the patriots database maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). -

The Working Life of Thomas Ferens 1848 – 1888

“The Southern World is my Home”: The Working Life of Thomas Ferens 1848 – 1888 Peita Ferens-Green March 2018 Word Count: 40,664 Contents Abstract 2 List of Figures 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 6 Chapter One: Religious Influences, Intercultural Relationships and Examination of the ‘Self’, 1848 – 1851 25 Chapter Two: Pastoral Pursuits, 1852 – 1871 59 Chapter Three: A Mixed Slice of Life, 1872 – 1888 84 Conclusion 108 Bibliography 114 1 Abstract This thesis is a case study of Thomas Ferens, a Methodist lay preacher from England. Utilising personal testimony, it follows his life in New Zealand from 1848 – 1888, focussing upon his various occupational pursuits to explore how his sense of ‘self’ affected his migrant experience, analysing how he navigated life in the settlement, and how he was influenced by the world around him. Typically, migrant scholars using personal testimony focus on those of a (literate) middle to upper class status. A focus on Ferens, however, provides a working-class perspective. He similarly offers a perspective on Methodists in the Scottish Presbyterian Otago settlement. This work engages with studies of missionaries, religion in New Zealand, intercultural relations and constructs of self/other. It also addresses the impact of runholding and declaration of hundreds in North Otago and the need for personal mobility, both geographical and occupational, in this early period of settlement. 2 List of Figures Figure 1 Thomas Ferens; photograph, n.d. Source: Ferens family records. Figure 2 Anon. Old Mission House, Waikouaiti, 1840, 1840. Source: Collection of Toitū Otago Settlers Museum. Reference 67_115. Figure 3 Margaret (Maggie) Ferens (nee Westland). -

October 9 Update 2FALL 2018 SYLLABUS Engl E 182A POETRY

Poetry in America: From the Mayflower Through Emerson Harvard Extension School: ENGL E-182a (CRN 15383) SYLLABUS | Fall 2018 COURSE TEAM Instructor Elisa New PhD, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, Harvard University Teaching Instructor Gillian Osborne, PhD ([email protected]) Teaching Fellows Field Brown, PhD candidate, Harvard University ([email protected]) Jacob Spencer, PhD, Harvard University ([email protected]) Course Manager Caitlin Ballotta Rajagopalan, Manager of Online Education, Poetry in America ([email protected]) ABOUT THIS COURSE This course, an installment of the multi-part Poetry in America series , covers American poetry in cultural context through the year 1850. The course begins with Puritan poets—some orthodox, some rebel spirits—who wrote and lived in early New England. Focusing on Anne Bradstreet, Edward Taylor, and Michael Wigglesworth, among others, we explore the interplay between mortal and immortal, Europe and wilderness, solitude and sociality in English North America. The second part of the course spans the poetry of America's early years, directly before and after the creation of the Republic. We examine the creation of a national identity through the lens of an emerging national literature, focusing on such poets as Phillis Wheatley, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edgar Allen Poe, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, among others. Distinguished guest discussants in this part of the course include writer Michael Pollan, economist Larry Summers, Vice President Al Gore, Mayor Tom Menino, and others. Many of the course segments have been filmed in historic places—at Cape Cod; on the Freedom Trail in Boston; in marshes, meadows, churches, and parlors, and at sites of Revolutionary War battle. -

Read Book the Eleventh and Twelfth Books of Giovanni Villanis New

THE ELEVENTH AND TWELFTH BOOKS OF GIOVANNI VILLANIS NEW CHRONICLE Author: Matthew Sneider Number of Pages: 499 pages Published Date: 30 Sep 2021 Publisher: De Gruyter Publication Country: New York, United States Language: English ISBN: 9781501518423 DOWNLOAD: THE ELEVENTH AND TWELFTH BOOKS OF GIOVANNI VILLANIS NEW CHRONICLE The Eleventh and Twelfth Books of Giovanni Villanis New Chronicle PDF Book He analyzes how these people deal with unexpected setbacks and new challenges. Complete Index to Volumes I, II, and III of Warbasse's Surgical Treatment (Classic Reprint)Excerpt from Complete Index to Volumes I, II, and III of Warbasse's Surgical Treatment Bones, diseases of, talipes due to, 111. What tools do I need to succeed. Rethinking Biased Estimation introduces MSE bounds that are lower than the unbiased Cramer-Rao bound (CRB) for all values of the unknowns. They didn't just luck into the success they have, they created it. " In If Nuns Ruled the World, veteran reporter Jo Piazza overthrows the popular perception of nuns as killjoy schoolmarms, instead revealing them as the most vigorous catalysts of change in an otherwise repressive society. 35 case studies to support a competency-based approach to teaching and assessment. Whether repairing existing components, fabricating new ones, building a race car, or restoring a classic, this is the one book to guide the reader through each critical stage. As this book is more challenging than most, it will occupy your mind and require more focus. Capturing the complexities and challenges of protecting water as a resource on the one hand and utilizing it as a service on the other, this thought-provoking book will prove a valuable resource for researchers and students of both water law, and the nexus of environmental law with human rights. -

Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sanko, Marc Anthony, "Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6565. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6565 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair James Siekmeier, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Mary Durfee, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Immigration History, U.S. -

What's in a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2019 What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795 Hannah M. Nolan University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Nolan, Hannah M., "What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795" (2019). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/2237 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nolan 1 Hannah Nolan History 408: Section 001 Final Draft: 12 December 2018 What’s In a Name: Political Smear and Partisan Invocations of the French Revolution in Philadelphia, 1791 - 1795 Mere months after Louis XVI met his end at the base of the National Razor in 1793, the guillotine appeared in Philadelphia. Made of paper and ink rather than the wood and steel of its Parisian counterpart, this blade did not threaten to turn the capital’s streets red or -

A. James Hammerton, Migrants of the British Diaspora Since the 1960S

Zitierhinweis Ruiz, Marie: Rezension über: A. James Hammerton, Migrants of the British Diaspora Since the 1960s. Stories From Modern Nomads, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017, in: Reviews in History, 2018, August, DOI: 10.14296/RiH/2014/2275, heruntergeladen über recensio.net First published: http://https://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/2275 copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. After Emigrant gentlewomen: Genteel poverty and female emigration, 1830-1914, Cruelty and Companionship: Conflict in Nineteenth Century Married Life , and Ten Pound Poms: A life history of British postwar emigration to Australia with Alistair Thomson, A. James Hammerton revisits post-war Britain’s diaspora through the prism of oral history in Migrants of the British Diaspora since the 1960s: Stories from Modern Nomads. This focus on oral history was also present in Speaking to Immigrants: Oral Testimony and the History of Australian Immigration, edited with Eric Richards in 2002.(1) The British diaspora is still one of the largest in the world with about 6.5 per cent of its population living overseas in according to figures from 2010–11, the result of decades of continuing settlement abroad rather than a recent development. Hammerton thus offers a compelling and highly timely study of what he terms the ‘modern drive to emigrate’. His book includes a wide variety of themes that have left an imprint on British society and marked the post-war period, such as the ethnic relations with the Windrush generation, the swinging sixties, and decolonization, among others. -

Migration in Britain

MIGRATION IN BRITAIN: WhAT ARe OuR CulTuRAl IdeNTITIes? This learning resource for teachers and students of Secondary Art and A Level Art focuses on a selection of portraits from the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. The resource could also be relevant for those studying Art History, History and Citizenship. Camila Batmanghelidjh by Dean Marsh oil on plywood panel, 2008 NPG 6845 2/32 MIGRATION IN BRITAIN ABOuT ThIs ResOuRCe This resource tackles the question of what British cultural identities can mean and how people who constitute that sector of our society have and do contribute to it in a variety of different ways. This resource relates to another resource in on our website entitled Image and Identity. See: www. npg.org.uk/learning Each portrait is viewed and examined in a number of different ways with discussion questions and factual information relating directly to the works. The material in this resource can be used in the classroom or in conjunction with a visit to the Gallery. Students will learn about British culture through the ideas, methods and approaches used by portrait artists and their sitters over the last four hundred years. The contextual information provides background material that can be fed into the students' work as required. The guided discussion gives questions for the teacher to ask a group or class, it may be necessary to pose further questions around what culture can mean today to help explore and develop ideas more fully. Students should have the opportunity to pose their own questions, too. Each section contains the following: an introduction to each portrait, definitions, key words, questions and two art projects. -

Philip Freneau - "A Poet of the American Revolution"………21

Contents Introduction……………………….……………………………………………...2 Chapter I Poets and Poetry during the American Revolution …………..…8 Chapter II Philip Freneau - "A Poet of the American Revolution"………21 Chapter III Literary analysis of Philip Freneau‘s poems………………….36 Chapter IV Using Philip Freneau‘s Poetry to Study a Foreign Language…..46 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………..57 The list of used literature………………………………………………………..59 1 Introduction In extraordinary session which was held in Samarqand in December 2010, I.A Karimov underlined that learning English language must be on the first plan of each young people as it is the main way of being on the equal line with young people of the developed countries, and teaching English must be on high level to prepare our youth as a competitive specialists in the world.. One of the prior tasks of development of Independent Uzbekistan suggested by the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan I. A. Karimov is the task of public education. The state first of all, must take care of the future generation. In his report I. A. Karimov paid great attention to foreign languages. With the adoption "About Education" in 1997 and "The national programme by training personnel" the additional measures and positive reforms were carried out at the universities of Uzbekistan. One of them is the department of "Uzbek and foreign languages". According to the Laws and Resolution of the Government directed to the improvement of teaching foreign languages, teachers of Uzbekistan work out a new program, syllabus taking into account the specialization of the universities. They reflect the link between the process of teaching and upbringing, include different types of independent work; special attention is paid to the development of communicative habit and skills so as the students could use foreign language in their practical, professional activity. -

Canadianism, Anglo-Canadian Identities and the Crisis of Britishness, 1964-1968

Nova Britannia Revisited: Canadianism, Anglo-Canadian Identities and the Crisis of Britishness, 1964-1968 C. P. Champion Department of History McGill University, Montreal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History February 2007 © Christian Paul Champion, 2007 Table of Contents Dedication ……………………………….……….………………..………….…..2 Abstract / Résumé ………….……..……….……….…….…...……..………..….3 Acknowledgements……………………….….……………...………..….…..……5 Obiter Dicta….……………………………………….………..…..…..….……….6 Introduction …………………………………………….………..…...…..….….. 7 Chapter 1 Canadianism and Britishness in the Historiography..….…..………….33 Chapter 2 The Challenge of Anglo-Canadian ethnicity …..……..…….……….. 62 Chapter 3 Multiple Identities, Britishness, and Anglo-Canadianism ……….… 109 Chapter 4 Religion and War in Anglo-Canadian Identity Formation..…..……. 139 Chapter 5 The celebrated rite-de-passage at Oxford University …….…...…… 171 Chapter 6 The courtship and apprenticeship of non-Wasp ethnic groups….….. 202 Chapter 7 The “Canadian flag” debate of 1964-65………………………..…… 243 Chapter 8 Unification of the Canadian armed forces in 1966-68……..….……. 291 Conclusions: Diversity and continuity……..…………………………….…….. 335 Bibliography …………………………………………………………….………347 Index……………………………………………………………………………...384 1 For Helena-Maria, Crispin, and Philippa 2 Abstract The confrontation with Britishness in Canada in the mid-1960s is being revisited by scholars as a turning point in how the Canadian state was imagined and constructed. During what the present thesis calls the “crisis of Britishness” from 1964 to 1968, the British character of Canada was redefined and Britishness portrayed as something foreign or “other.” This post-British conception of Canada has been buttressed by historians depicting the British connection as a colonial hangover, an externally-derived, narrowly ethnic, nostalgic, or retardant force. However, Britishness, as a unique amalgam of hybrid identities in the Canadian context, in fact took on new and multiple meanings. -

Rethinking Biological Invasion Jonah H

The White Horse Press Full citation: Johnson, Sarah, ed. Bioinvaders. Themes in Environmental History series. Cambridge: The White Horse Press, 2010. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/2811. Rights: All rights reserved. © The White Horse Press 2010. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. For further information please see http://www.whpress.co.uk. Bioinvaders Copyright © The White Horse Press 2010 First published 2010 by The White Horse Press, 10 High Street, Knapwell, Cambridge, CB23 4NR, UK Set in 10 point Times All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, in- cluding photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-874267-55-3 (PB) Contents Publisher’s Introduction Sarah Johnson iv Strangers in a Strange Land: The Problem of Exotic Species Mark Woods and Paul Veatch Moriarty 1 Nativism and Nature: Rethinking Biological Invasion Jonah H. Peretti 28 Exotic Species, Naturalisation, and Biological Nativism Ned Hettinger 37 Plant Transfers in Historical Perspective William Beinart and Karen Middleton 68 Weeds, People and Contested Places Neil Clayton 94 Re-writing the History of Australian Tropical Rainforests: ‘Alien Invasives’ or ‘Ancient Indigenes’? Rachel Sanderson 124 Prehistory of Southern African Forestry: From Vegetable Garden to Tree Plantation Kate B. -

English Language Diaspora and the Hit-And-Miss…

Haque, English Language Diaspora And The Hit-And-Miss… ENGLISH LANGUAGE DIASPORA AND THE HIT-AND-MISS EXPERIMENTATION WITH ENGLISH CURRICULUM IN BANGLADESH Mr. Md. Azizul Haque Stamford University Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Abstract Despite the common diasporic origin English in Bangladesh is neither a native nor a second language, but a foreign language, in countries like India and Pakistan, English is used as the second language. The chronological history of English in Bangladesh has both political as well as social elements, which influence the learning of English at every level of education. In the mid-90s there was a growing demand from the educationists in the country to change the English curriculum as per ‘needs analysis’, and the curriculum is restructured aligning with the communication needs and the syllabus was largely transformed into a communicative one. Yet research explores that the needs are not served for the learners tend to by- pass the cognitive part of the language learning—thus failing to communicate properly. Now, in the second decade of the new millennium English curriculum along with other subjects has been made ‘creative’ at pre-tertiary level, but debates are still on to evaluate whether the system complies with the current practices prevailing within the institutional premises. The total picture thus presents a very confusing answer to the questions why all these efforts are being futile and why the English language teaching fails to touch the three main domains of learning—the cognitive, the affective and the psychomotor. The current study wants to explore whether such experiments with the curriculum and the dilemma of receiving or rejecting the idea of acculturation with largely an anti-colonial mindset hinder the desired performance of the language.